bathology noun /bɑːθˈɒlədʒi/ (plural bathologies)[uncountable] the study of the ontology, functions, history, and poetics of bathtubs.

During modern human history but especially during the 21st century, the primacy and the centrality of human and humanism within the patterns which we customarily employ when thinking about art, technology and the world in general have been criticized. In the light of recent crises which have been perceived as human-induced, this critique has become ever more important and all creative ways of inviting ontological inquiry into humans as well as non-human species, diseases and not least objects are certainly welcome on a wider and far more applied scale than ever before.

The posthumanist literary scholar Cary Wolfe, the editor of a series of books ‘Posthumanities’, has emphasized that posthumanist theory has no intention of rejecting humanism nor the values related to it but rather aims to consider how values like justice, tolerance, equality, dignity, human rights, etc. have become a part of the definition of uniqueness and exceptionality of the human kind. The Polish philosopher Ewa Domanska decried already a decade ago, ‘I think that at present the theory of the human and social sciences is a step behind what is going on in the contemporary world in terms of environmental cataclysms, the crisis of climate change and, in terms of technology, genetic engineering and nanotechnology (plus the spread of global capitalism), and thus must bring under consideration the new situations and phenomena that technology has created. Theory has to ‘catch up’ with the main problems addressed by current research since existing theories and interpretive tools are inadequate to account for the rapidly changing world.’1 Now, ten years on, it is most definitely an opportune moment for a re-evaluation of this mass of theory at a time when a serious shift in our (Western) luxurious way of life is suddenly and violently called for. A non-human-centred ontology could hopefully contribute to the advancement of global and climate-conscious practices in all walks of life, as well as highlight the sheer multitude of anthropogenic and influential objects produced in an ever-increasing amount.

Indeed, by 2020 there exist even more radical schools of thought that aim to unhinge objects and their functions from humans altogether, or, to be more precise, to level the object-ness of humans with objects, to recognize the object-ness of human beings. Graham Harman, the founder of the philosophical discipline of Object-Oriented Ontology has proposed an in-depth object-centred approach, ‘A truly pro-object theory needs to be aware of relations between objects that have no direct involvement with people.’2 Taking into account all objects and the time spent thinking about objects, conjuring new designs, fighting and loving them, this wealth of theory should now be applied in order to test and confirm if a non-anthropocentric ontology truly offers a shift in perspective, and in practice. It seems disciplines that work with space, and, of course, objects, are best suited for this: architecture, design, and perform ing arts. There are scores of examples from recent local history where monuments, buildings and roads as well as performances and productions have divided masses as well as families, where objects which carry a lot of power, one should even say agency, have changed the course of history. As an illustration, I present a case study on the object known as ‘bathtub’ in the following, but the method can most certainly be extended to more complex, larger, or also minuscule, objects and object-assemblages.

Case study: bath

Bathology is an example of a possible artistic method which attempts to take into account the object’s perspective, the object as is. The budding bathology was inspired by the Lithuanian artist Marija Baranauskaitė and her exploration of sofanity. Namely, in 2018 she started developing the Sofa Project, a conceptual clowning performance where the target audience is not sentient, not even human but a sofa. In addition to being entertaining to human audiences as well as object-audiences (hopefully), it is also compelling for theoretical reasons, evoking among other things musings in the vein of Philosophy of Technology, Critical Posthumanism and Object-Oriented Ontology as well as exercises in non-anthropocentric thinking, and attempts to place something other than a human in the position of a subject.

Baranauskaitė asks ‘how much consciousness is needed to be an audience member or a performer?’3 Presented in various places around the world and also twice in late 2019 in Estonia—at the EPICIRQ showcase for Baltic professional circus in early October, and once more at Tallinn Fringe Festival in December—, the Sofa Project sees furniture as a worthwhile audience.

Inspired in turn by dance artists Krõõt Juurak and Alex Bailey and their Performances for Pets, the Sofa Project compels audience members to embody a sofa, hide their faces, hands, and not to laugh out loud while the artist presents a half-hour of movement, sound and monologue for a rather surprised lot of soft furniture. Professor Jessica Ulrich notes about Performances for Pets that humans can learn something from these performances meant for animals, too.4 The shift of the addressee offers the possibility of observing meticulously the ways in which animals react to movement, smell and sound. Creating for a different species exposes the categories in which performances for people are constructed. Continuing with alternative audiences and planning a performance for an inanimate observer, even as a mere thought experiment, requires a thorough observation and analysis of the particular object. Bathtubs and sofas do not react in any perceivable way to human performances, thus the only material for analysis is the human action during the preparation of such a performance, while focus is put exclusively on the object ‘audience member’, and the reaction, i.e. emotions elicited by that activity: disappointment, bewilderment or indifference.

Try this at home!

The first exercise of bathology is a long soak in a hot bath. Practiced by billions of people around the world (not everyone, the massive availability of baths is a recent luxury and by far not universal), full-body submersion and the subsequent removal of the defunct surface layer of skin, also known as the practice of bath, results in water which is considered unclean. While the development of public health and safety owes a lot to the scientific discoveries of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as well as the growing availability of the public water supply system, the 20th century has but deepened the obsession with cleanliness and soap (cf. Barthes Mythologies 1957), and a pandemic will certainly create a detectable global wave of germaphobia, followed by a surge in the production of disposable PPE (personal protective equipment), hence pollution, etc. On the other hand, the critical posthumanist philosopher Stacy Alaimo has stressed the political importance of reconceptualizing materiality and the importance of material agency, especially for environmentalism and feminism. She has created the concept of ‘trans-corporeality’, which ‘entails a radical rethinking of the physical environment and the human bodily existence by attending to the transfers across those categories’.5 Taking into account the multitude of flora and fauna, also harmless viruses and inanimate debris (e.g. microplastics) that reside in human epidermis, it is probably naive to think that the mere exitus of bath-water restores the discreet border between the object, bathtub and the human body. Critical posthumanists are of the opinion that such a limit cannot be anything more than an artificial mutual agreement. Bathtubs as well as people are porous. By the end of a soak there is considerably more human within the water as well as within the micropores of the bathtub as there was in the beginning. Opening the drain hole is the trans-corporeal human being’s exit.

The second exercise of bathology is the ultimate reverse anthropomorphization, actually morphing into an object, enacting a bathtub. Marija Baranauskaitė proposed the activity during the artists’ laboratory Performing for Objects led by dance exploration platform Bitės6 in January 2020, when five artists from Lithuania and Estonia convened in Vilnius to perform for sofas, mirrors, cameras, washing machines, and bathtubs. The performer, in order to focus the whole attention on the object, must embody it. First, the object is to be emulated for 30 minutes. I spent the first half-hour in a darkened bathroom beside a real-life tub on the hard floor, trying to copy it, first by slowing all of the senses, and most importantly, the mind. The difficulty of achieving this meditative state highlighted the extreme differences between the objects’ and human temporalities. While bathtubs are not immortal, they are certainly perishable and do not react well to surface damage, which is similar, of course, to humans. But the daily changes of light and darkness, generations of bio-organisms, centuries or seconds must all equally be simultaneous blips for an object and do not register. After the first task the exercise continues with ‘being human’ for 30 minutes. The curious sense of ‘playing human’ arose in all of the participants of the laboratory immediately. How to human? For the subsequent 30 minutes a half-human-half-object must be performed. The performer is free to choose the method of dividing the body into two radically different halves of human and object. Whether imaginary hemispheres, poles, layers or a chimera-approach of a seamless blend of human and bathtub particles, the exercise is decidedly disconcerting, bringing about the realization of one’s own materiality and the true rarity of organic life which is nevertheless the same exact chemical elements composed in ingenious patterns to form life, or a bathtub.

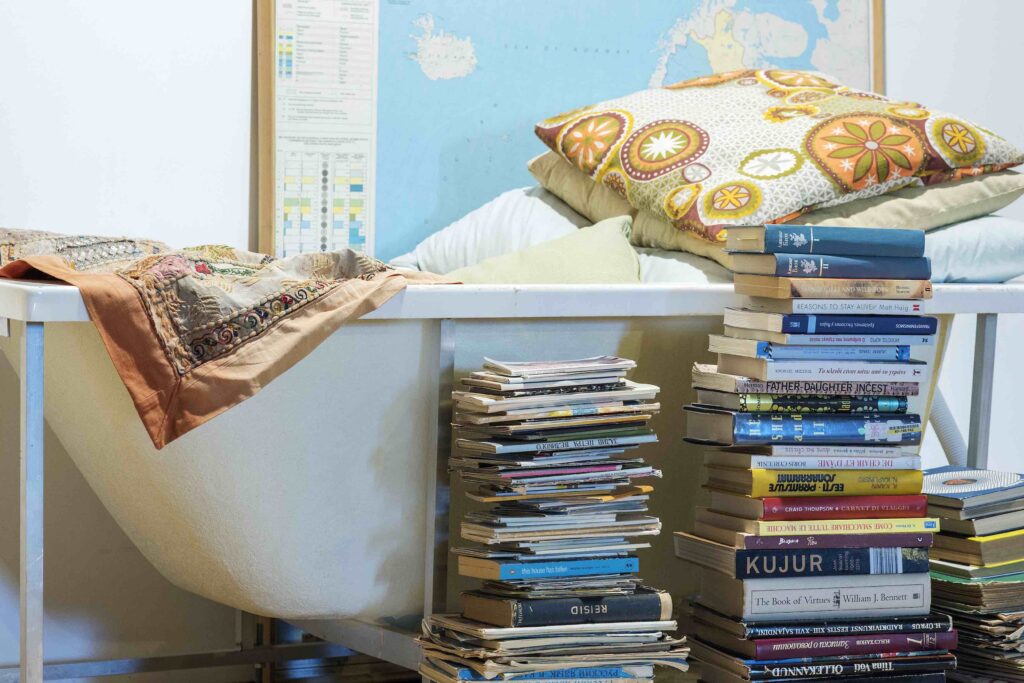

Artefacts are brought about by simultaneous human need and intention. There exists a certain physical ability that can be translated into a physical form. Human intention is the intellectual capacity to recognize the need of translation and to create artefacts accordingly. Professor Peter Kroes of Delft University in the Netherlands has described the same in terms of functions and functional properties. Paraphrasing Kroes’ structures it can be said that the technical artefact bathtub has two mutually valid functional properties, which can be modelled as a ‘for φ-ing’ (‘x is for bathing’) and ‘a φ-er’ (‘x is a bathtub’). An object x may have the functional property ‘for φ-ing’ without having the functional property ‘a φ-er’, that is, an object x may be for bathing without being a bath (without being an instance of a particular technical artefact kind).7 It must be also taken into account that the ‘for φ-ing’ functional property of a bathtub is fluid. Even the most expensive designer bathtub can just as well be used for a multitude of purposes other than a bath, for rituals, storage, crime and justice, and might at some point end up in a garden somewhere, enacting the functional property of a reservoir of irrigation water.

Following that, the third and last exercise of bathology is one of speculative genealogy. There is confirmed evidence of plumbing systems, of copper pipes beneath palaces already from the Bronze Age Anatolia, but it can be claimed with certainty that the inventor of a ‘bath’ is innominate and predates Homo Sapiens. The object ‘bathtub’, whether it be wood, copper, tin or marble, is a tiny copy of a concave depression in the surface of the Earth that has accumulated water. From that point of view the bathtub is a cultural artefact, a linguistic act. Natural recesses and caves, teacups and saucers, boats or even leaves on a tree can become bathtubs by assignment of the function of a bathtub. Foucault’s example of an ancient heterotopia, of a ‘counter-site, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted,’8 is a garden. A bathtub, following that, contains all of the history of evolution since the very first organisms developed in the grand bathtub that is the ocean, the incubator of organic life.

Professor Ulrich points out that pets have been co-habiting, as well as co-evolving, with humans for millennia. ‘The history of domestication can no longer be regarded as a one-way development but as a mutual taming. Just as much as early humans made dogs, early dogs made homo sapiens.’9 There are certain animals which have changed the way in which human beings and their culturehave evolved, which have tamed humans. How have objects, a portion of which are artefacts, tamed, or better yet, moulded the human experience, or even human morphology? While an artefact, the shape of this primitive bathtub object is nonetheless motivated by human phenotype. If human beings were not between one and two metres tall and quite compact but more like octopi, elephants or colonies of bacteria, our bathtubs might look decidedly different. It is intuitive for a human being to be inside a bathtub and not the other way round. Human beings start life floating in an organic sensory deprivation tank, children are compulsively bathed almost nightly, they practice their first ‘sea’ in a bathtub, not to mention the increasing popularity of partūs in aqua, water births, and on the other hand, the countless lives that have ended in a tub. Baths are dangerous, mysterious, communal and private at the same time.

There are valuable lessons to be taken from these exercises which are by no means exhaustive. Living with objects, as objects, or combined with objects might result in an in-depth, embodied experience of object-ness which, unfortunately, cannot endure for an extended period of time but can ephemerally open up a novel relation with our surroundings and its pervasive, all-conquering functionality, i.e. compatibility with the human corpus. Bathology (or automobility, or sofanity, etc.) can refurbish and draw closer art objects or conceptual pieces that at first glance might be rejected as incomprehensible. Leaving aside all which ‘the artist intended to say’ and allowing the object to speak, new and unexpected avenues of interpretation might open up far more effortlessly. It has additionally produced a desire to create specific objects which invite the human being to engage in contemplations on object-ness, but these must be left for the second phase of this inquiry.

The first phase has resulted in two maxims that await application to many more objects and object-assemblages:

Firstly, the minimum characteristic of bath-ness depends on the system of measurement. Whether it be intention or need, the assignation of function or cultural implications, the minimum characteristic might be a language act, concavity, or the designer’s idea. But the most effective way of experiencing the liminal approach to the alluring ideas of object-ness as well as human-ness seems to be the spending of time with an object, whether in thought, in the presence of, or as the object proper.

Secondly, bathtub is inevitable. It is at the same time the consequence as well as the catalyst of human evolution. When taking into account that it has not been ‘invented’ by an ingenious, all-powerful, shining and individual original human author, and by highlighting the porous relationships between a human and a bathtub body, it becomes a leveller, and humbles the bather soaking in a tub like a human-sized teabag in a trans-corporeal cup of human brew.

KAISA LING is a freelance professional in culture: a blues singer, radio host, and critic.

PHOTOS: Laura Kuusk

PUBLISHED: Maja 101-102 (summer-fall 2020) Interior Design

1 Ewa Domanska, Beyond Anthropocentrism in Historical Studies – Historein.10/2010, lk 119.

2 Graham Harman, Immaterialism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016, lk 6.

3 The biography of Marija Baranauskaitė https://www.epicirq.com/the-sofa-project-by-marija-baranaus

4 Professor Jessica Ulrich’s lecture at the conference Animal Forms & Formulas at Sophiensaele, Berlin – On the human-animal-relation in contemporary performance , 01.10.2017. http://www.performancesforpets.net/text

5 Cecilia Åsberg and Rosi Braidotti, A feminist companion to the posthumanities. – Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018, p 49.

6 The website of the dance platform Bites http://bitesdance.lt/

7 Peter Kroes, Technical Artefacts: Creations of Mind and Matter. Delft: Springer, 2012, lk 8.

8 Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité Oktoober, 1984; (‘Des Espace Autres,’ March 1967 translated from French by Jay Miskowiec)

9 Jessica Ulrich’s lecture http://www.performancesforpets.net/text