PÄRNU RAJA KINDERGARTEN AND SWIMMING POOL

Location: Raja 7, Pärnu

Architecture: Margit Aule, Katrin Vilba / KAOS Arhitektid, Triinu Nurmik / Projekt O2

Interior architecture: Margit Argus, Katariina Teigar / KAOS Arhitektid

Landscape architecture: Mirko Traks, Karin Bachmann, Uku Mark Pärtel, Kristjan Talistu, Juhan Teppart / KINO maastikuarhitektid

Structural design: Ever Haabmets / Projekt O2

Client: Pärnu Linnavalitsus

Constructions: Projekt O2

Main contractor: Nordlin Ehitus

Total area: 4560m2

Completed: 2020

One of the most important traits in the 21st century is considered to be creativity. What kinds of spaces set the cornerstone for a creative personality? Let us examine the interiors and exteriors of Raja Kindergarten in Pärnu.

The first Estonian-founded Estonian-language kindergarten in the country was opened in 1905, in Tartu.1 Before that, childcare had been organised by Baltic Germans, and it was accordingly German-speaking and German-minded. This century has already witnessed all kinds of ideologies, and the current year of coronavirus will likewise leave its mark on architecture and space management.

Interestingly, Pärnu Raja Kindergarten, which was opened last year, reflects the new coronavirus-era world order as if it was already designed with that in mind. However, the design process began before the new virus-shaped reality had set in.

Pandemic space

Raja Kindergarten is planned in a way that lets you enter each kindergarten group from inside the building as well as their own separate yards, through small designated vestibules. Thus, children and their parents can head straight to their own group without having to get into contact with children and family members from other groups.

If we reflect on how the coronavirus is affecting architecture and public space, we can already see that segregation is and will probably remain the keyword. When it comes to combating the virus and its spatial manifestations, in many ways we have regressed to medieval methods.

In 18th-century Paris, it was namely a plague epidemic that led to the rearrangement of urban space and a new recording-keeping system that enabled the authorities to keep track of the citizens. Living spaces, houses and streets were numbered and the number of residents in each building was noted down. The authorities sent out daily patrols to record how many people in one or another household had fallen ill, and to mark this information also on the facade of the building. Only the people living in the building were allowed to enter and leave it, and even they could do so only at a designated time.2 Similar practices—even though in digital form—could be seen during last year’s epidemic in many European countries. A couple of years earlier, these practices would have struck us as dystopian violations of human rights.

Before the rearrangements of baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s era, cemeteries were situated in the heart of Paris, but due to the plague epidemic, they were moved outside the city boundaries so that the contagion would not spread to healthy citizens.

Thus, one of the new tendencies in our pandemic world consists in creating isolation through spatial categories and architectural planning. A gentler example of this can also be found in Raja Kindergarten.

People have long feared the so-called Other—whether it be someone of a different ethnicity, race, culture or religion—and demonised them in order to facilitate hate toward them, but now, the so-called others could be one’s own closest family members. It is feared that meeting with one’s family members could lead to an infection and even death. Grandparents fear that they might die due to contacts with their children and grandchildren. This kind of daily life is extremely isolating and alienating.

Creative space

In essence, kindergartens are also disciplinary institutions that submit to the governing ideology and participate in shaping suitable subjects for the system. Thus, the design of kindergartens is never arbitrary, but reflects the dominant childcare-related social beliefs and norms.

However, another recent tendency is the rise of new peripheral communities whose principles include having smaller and more child-centered kindergartens and schools.

A good case in point is the new Waldorf school in Kõpu, Hiiumaa. The school was founded in February this year as a private initiative, and while it is situated in an old schoolhouse, it carries a new mentality and tries to avoid reproducing Industrial Revolution-era educational principles.

Looking at the spatial planning of most kindergartens and schoolhouses, however, we can see that they still carry the old mentality, which also reflects in their architecture.

Even though children spend much of the year in educational institutions, I think that the role of the latter in children’s path of personal development should not be overestimated. Personally, I went to a completely ordinary kindergarten and school in Tartu’s Annelinn district, but can barely remember these environments from my childhood. On the other hand, I have detailed memories of all the summers I spent at the my grandparents’ seaside farm in Tahkuranna.

Thus, while I believe that good architecture and design do have an important role to play, significant cornerstones of a creative personality are set in environments that have evolved on their own and do not submit to human-imposed parameters.

Kindergarten as a spaceship

The building of Pärnu Raja Kindergarten is multifunctional, meaning that it gathers under one roof the kindergarten as well as Pärnu’s public swimming pool. For the kindergarten, it is definitely a very nice bonus that children can relish the joys of water and something special also in the cooler season.

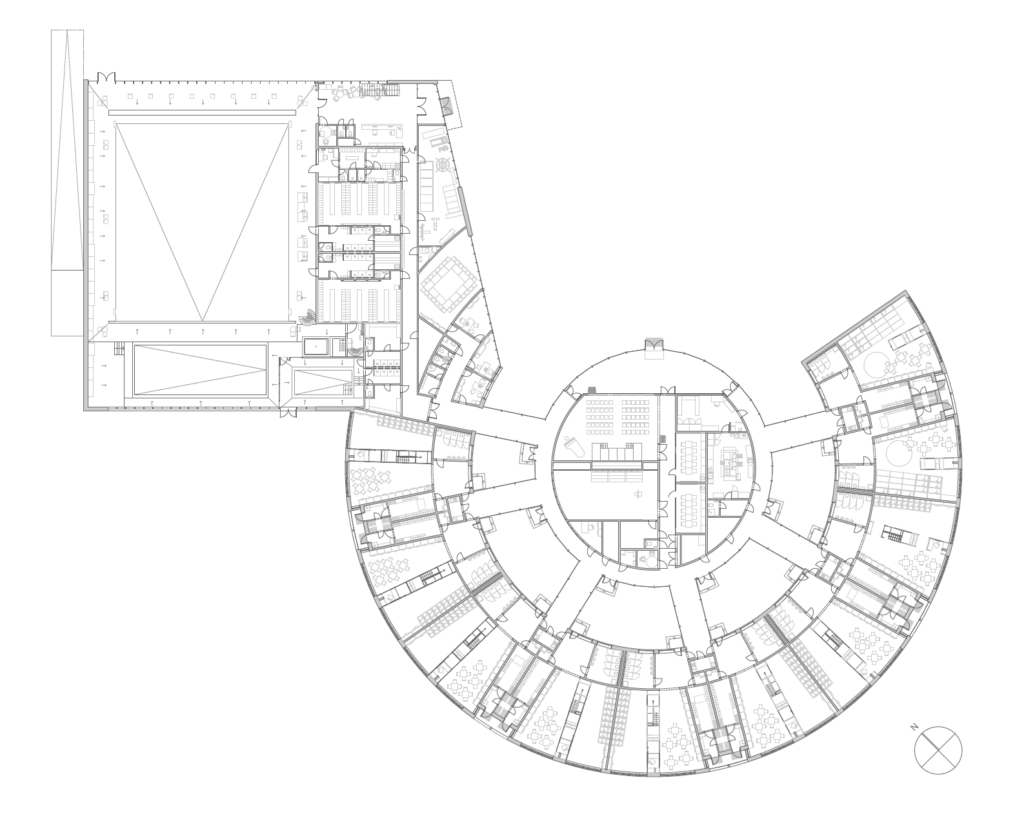

The central part of the kindergarten building accommodates common areas and is circled by group rooms. According to KAOS Architects, the rooms were positioned in accordance with essential kindergarten logistics and feedback from the employees, in order to ensure smooth movement to the group rooms and outdoors playtime during the day.

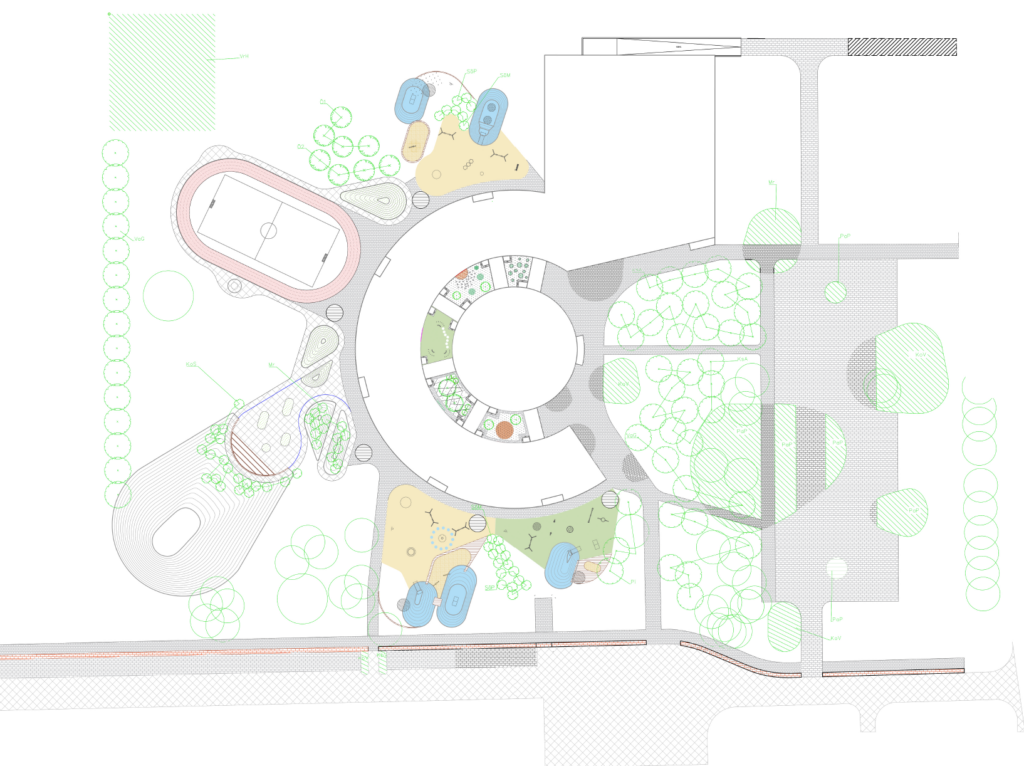

Movement between the common areas in the heart of the building and group areas takes place through glass galleries. The gable roofs of group rooms highlight the fact that the large building accommodates separate spaces for each group, but together, they form a kind of village within a playful landscape. Playgrounds are positioned radially around the building and structured by landforms.

On the outside, KINO landscape architects have created various playgrounds, sledding hills, trampolines, swings, carousels and areas for physical activities.

Each group has its own small yard where it is possible to organise educative and exciting activities for the children. There are also small pots for growing potherbs.

This kind of approach embodies the principles of educational innovators Montessori and Steiner,3 who believed that the best way for children to learn and develop is to imitate adults in their activities, rather than to play only with their designated toys.

Even though the contemporary Western world regards this kind of approach as so-called alternative education, this is precisely how children acquire their essential life skills. Small children try to do everything their parents do and have their own appropriately-sized tools for it. The approach urges us to trust the intrinsic astuteness of children and, most importantly, to trust ourselves as parents. The latter is not exactly the strong suit of the average contemporary Western parent.

This was also pointed out by the kindergarten teachers of the outdoor kindergarten in Tartu, when they were interviewed by Eva-Maria Truusalu for her MA thesis in the Estonian Academy of Arts’ interior architecture department on different types of kindergartens. In Tartu outdoor kindergarten, children spend most of the day outside, regardless of the weather. They spend their time in the territory of the Barge Yard, which does not look like a typical playground for children, but rather like someone’s backyard full of jumble and scrap. The point is precisely to have children create their own amusement park by letting their imagination run free. A teacher emphasised in the interview that the most important thing about this kind of an unconventional kindergarten is trust—i.e., that the parents would trust themselves and the teachers, and entrust their kids to such an unregulated environment, where everything is not round-cornered and made of plastic.

The inner space of kindergarten

The interior of the group rooms in Raja Kindergarten has a modernist and minimalist form, which has become the signature style of KAOS. Each group room is divided into two zones. On the one side, there is an area with small tables and chairs, where children can draw and do their art projects; the other side is the sleeping area. Meals are prepared in the kindergarten kitchen, which is situated in the middle of the complex, and then delivered to each group. Thus, there is no separate room for a canteen.

Between the two zones, there is a plywood stand with a built-in slide and playing nests on different levels. The teacher’s desk is also positioned in the middle of the room, which ensures a good view of both zones. In truth, this reminds me a bit of Bentham’s Panopticum,4 but then again, I guess all educational institutions are essentially tiny models of surveillance societies.

Built-in plywood lockers have nice rounded windows on different levels that help the children and also teachers to find what they are looking for without having to dig through everything.

The arched forms and pastel tones of bathroom doors exude a sly aura of 1950s Hollywood.

In the gym, ladders on the walls can be pulled down in order to create seating platforms. Next to the gym, there is an assembly hall with a modular stage. The hall can be enlarged by pulling back the glass walls on its two sides, making it much more spacious and extending it all the way to the main entrance of the kindergarten.

The small inner yards of Raja Kindergarten feature tiny, child-sized benches and forests of wooden sticks, which, according to the head of the kindergarten, are very much enjoyed by the children.

Chaos-free interior

The building has a clever plan and spatial solution, but I would have expected a bit more chaos from KAOS Architects—that is, bolder boundary-crossing and experimentation. Indeed, why not take a more playful approach to the interior and stimulate children’s imagination with a chaotic environment? For example, the indoor spaces could also have some interesting trees and bushes growing there that would enliven the room and clean the air during the cold season. The rooms could also have swings and large bouncy mattresses for children to jump on. Outside the building, KINO landscape architects have got all of this covered with different solutions, but I think that the indoor spaces could fit some more creative chaos.

Even though KAOS has stayed true to its much-acclaimed minimalistic style, which surely makes taking care of kindergarten hygiene easy and convenient, I found myself thinking that their kindergarten and kindergartens in general could be much more cosy than we are used to having. Sterile kindergartens fail to evoke the kind of safe and cosy environment that you have at your grandparents’ farm, where even most restless characters find comfort.

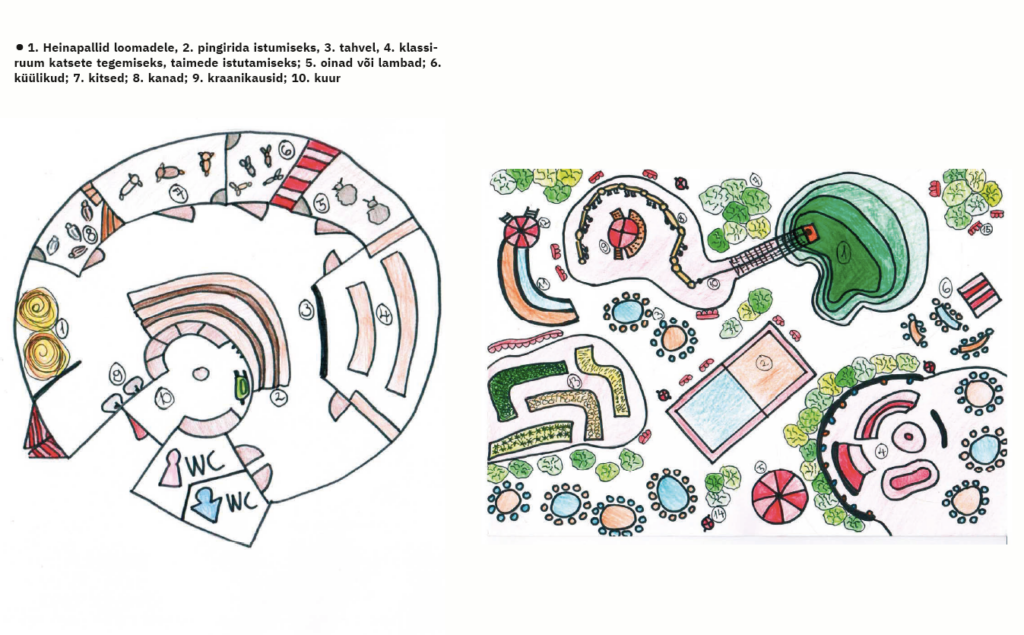

Why not ask children themselves the next time, what kind of kindergarten would they like to go to? Involving adult community members in designing their living environments is slowly becoming the norm, but asking the youth and children about their spatial preferences is still in infancy.

Children’s imagination is not constrained by current trends and they might propose solutions with a downright baroque aesthetic, but surprising level of functionality. This is something that I often see in the School of Architecture when brainstorming with younger groups for solutions to various spatial problems. These projects show that even primary school students know very well what kind of environment they would actually enjoy.

Young visionaries

The Urban Laboratory has organised student competitions—“My Dream Schoolhouse” and “My Dream Schoolyard”—which have shown that young people would prefer to study in environments that are spatially abundant and playful, and where flora and fauna form a part of the space.

Young people also emphasise that the environment should be cosy. The winner of the 2014 “My Dream Schoolhouse” competition was Kadri Hebo Kukumägi (supervised by Jaanika Kall) with her work CLOSENESS TO NATURE, in which her schoolhouse design included indoor bonfires under glass domes and a gliding tube between floors.

The winner of the 2015 “My Dream Schoolyard” competition was Heneliis Notton (Saue Gymnasium, supervised by Ave Kongo) with her work RURAL LIFE—a symbiosis between new and old, the schoolyard design included both a skatepark and barn for farm animals. The young landscape designer has intuitively understood that creativity is born when crossing old with new and letting it get wild. Unfortunately, our school system can, to put it mildly, suppress this natural knowledge, and after graduating from a university, it is already much harder for professionals to come up with these kinds of innovative solutions.

The work—just like many others that were sent to the competition—also reflects the youth’s yearning for authenticity, which is constantly decreasing in our artificial environments, regardless of how comfortable and hi-tech they become. Growing into a creative person requires a lot of trial and error that eventually leads to finding and accepting oneself. This cannot be achieved behind a computer screen or in a sterile, regimented environment only.

Conclusion

This brings us to a broader question—why do we still have to write all of this in 2021? Many who lived in the oppressive conditions of the Soviet Union probably thought back then that by the time we get to the next century, our society has been thoroughly transformed. Unfortunately, as we can see, things have moved rather in the opposite direction—a certain kind of lush, untamed freedom that could still be experienced from the 1970s to 1990s has now been lost for good, and the totality of the virtual surveillance society that we have today is unprecedented.5

I believe that the generation of today’s 30- to 50-year-olds, who went to Soviet kindergartens, schools, and lived in blocks of flats, managed to acquire their creative and free thinking thanks to the oases of freedom that awaited these children of the 1970-80s at their grandparents’ homes—ideally in the countryside, but perhaps also in cosy suburbs or garden cities.

Their importance lied namely in the contrast that they provided, and the fact that they enabled the transmission of native culture in a kind of umwelt that was antithetical to the monotony of standardised kindergartens, schools and residential districts all over the Soviet Union, and all the ideological content that was crammed into heads in these places.

Our current pandemic reality, still new and strange to us, is only beginning to affect the face of architecture and space. I hope that we are able to counter all the mental and physical control with an antidote brewed from our roots, genius loci and heritage. These are fortunately still felt by our children and young people on an instinctive level, but the duty of keeping them alive lies with each member of society.

MADLI MARUSTE is an architectural semiotician and teacher in the School of Architecture. She also writes on Instagram at “Eesti Ruum” about architecture, heritage and space..

PHOTOS by Tõnu Tunnel

SEE also: A Photo Essay of Raja Kindergarten by Paco Ulman

Commentary

FEE TAMM

Headmaster of Meremäe School in Setomaa (known for being a flexible community school, where children with learning disabilities study together with regular children)

1. How come the field of education is changing so slowly in Estonia, and why are children and youngsters still studying with a similar programme and in similar environments as their parents who grew up in a completely different system?

“Slow” and “fast” are observer-relative. Changes are largely invisible to the broader public: innovation in education often comes into focus only when it is adopted into law.

The first reason is definitely that the standardised school system largely works, and changing it radically would mean replacing it with something for which there is no evidence that it would work.

Second, perhaps it has to do with a lack of imagination and points of comparison: heads of education and teachers (not to mention parents) do not have enough opportunities to observe and analyse the pros and cons of alternative systems. The general principles of the school system are similar all over Europe, and allow for so-called alternative approaches and homeschooling for children who do not wish to partake in “normal” learning for some reason.

2. Why are the Waldorf and Montessori systems, which are nearly 100-year old, still regarded as alternative education?

Because they offer an alternative to the regular system. However, teachers and heads of education are sufficiently knowledgeable today to selectively use methodologies also from other educational philosophies. But this very much depends on the individual attitudes and preferences of the teacher.

3. What would make the education system reflect our times better?

Many necessary and innovative requirements—regarding general competences, the importance of creativity, integration, etc.—have been stipulated by the state, but not uniformly applied. Teachers are aware of the new approaches, but adopting them is often not supported by the existing textbooks or school environment. It is as if the system has been cosmetically changed, but the nature of the change remains incomprehensible and inaccessible to the parties: the lack of support mechanisms means that the energy of the teacher is spent on other things than substantive professional development.

PUBLISHED: Maja 104 (spring 2021) with main topic What’s happening?

1 Eva-Maria Truusalu, „Environment initiating play: kindergarten as an abstract play landscape“, (EKA sisearhitektuuri osakond (ENTU) 2019), pp. 19.

2 Michel Foucault, “Of other spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias”, in Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory, ed. Neil Leach (New York: Routledge, 1997), pp. 177-78.

3 Eva-Maria Truusalu, „Environment initiating play: kindergarten as an abstract play landscape“, (MA thesis, Estonian Academy of Arts, 2019), pp. 16−17.

4 Michel Foucault, „Panopticism“. (Teoses: Neil Leach (toim) 1997a [1977]), pp. 356−367.

5 Olli Lagerspetz, „Mustuse filosoofia. Raamat maailmast, meie kodust“ (Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2020).