TÜRI MIDDLE SCHOOL AND SPORTS HALL

Location: F. J. Wiedemanni tn 3a, Türi linn, Türi vald, Järva maakond

Architecture: Risto Parve, Kai Süda, Heldi Jürisoo, Marju Tammik, Margit Valma, Martin Kinks / KARISMA Architects

Interior architecture: Ville Lausmäe, Gerly Vaikre / VL Interior Architecture

Landscape architecture: Tiina Tuulik / Järve & Tuulik architectural office

Structural Engineer: E. Kivi Inseneribüroo, Sirkel & Mall

Construction: Merko Ehitus Eesti

Commissioned by: Türi Vallavalitsus

Total area: school 4242 m² + sports hall 3707 m²

Competition brief: Estonian Association of Architects

Competition: 2017

Project: 2018

Completed: 2020

Türi Middle School is a well-executed example of a contemporary school—breaking preconceptions about the organisation of space, encouraging new practices that involve alterations by the users, and offering spatial solutions for socialising as well as withdrawing.

I have vivid memories of my young architect’s internship in Copenhagen from about 12 years ago. The highlights of this experience abroad were the numerous architecture tours that also included visits to new school buildings in remote neighbourhoods of the Copenhagen metropolitan area and smaller Danish municipality centres. What I saw there struck me as extraordinary at the time, given that I was coming from the context of the Baltic states. Both the outward appearance and inner qualities of these environments left a strong impression and expanded my understanding of school beyond thinking of it as simply a type of building with a number of classrooms. School is not merely a place for absorbing basic knowledge. It is a social construct and, to paraphrase the Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger,1 an ever-changing stimulating environment where one learns to socialise and interact—a place for learning to learn. School is the world in a nutshell and a model of community where learning goes beyond the curriculum.

Luckily, these days, there is no need to travel as far for an experience similar to the architecture tours of my internship. Several outstanding school projects for general education (e.g., Exupery International School, Liepaja State Gymnasium No. 1, and Adazi Primary School) and special education institutions (Saldus Art and Music School, Dobele Music School) have been developed in Latvia over the recent years. But such outstanding examples have resulted rather from the competence of architects and involvement of capable clients than any state policy. In Estonia, on the other hand, new learning concepts and changes to school infrastructure were introduced with the education reform. Noticing an increased demand for school design projects and a need for adequate school environments, the Estonian Association of Architects (EAA) organised a conference and developed and published guidelines for designing environments consonant with contemporary learning concepts.2 The EAA has also promoted building new schools to smaller municipalities. Türi is definitely an example of the latter—a medium-sized town in central Estonia with a population of about 5000 people.

School as a new centre for Türi

The two-storey complex consisting of the school itself and a sports hall was completed in 2020. It was built on the exact site of a former Soviet-built school—a standard H-shaped school building. Although the latter was physically and morally outdated, demolishing and replacing it was met with some resistance and bafflement from local residents. However, since its inauguration, the complex has become an important addition to and almost like a new centre for the town, having a strong impact on the community and enhancing the local life. Not only are the direct users enthusiastic about the project, but the wider community also feels connected to it. The site has no strict boundaries—separate access to the sports hall and absence of fencing invite locals to use the area for recreation and various activities after the school hours.

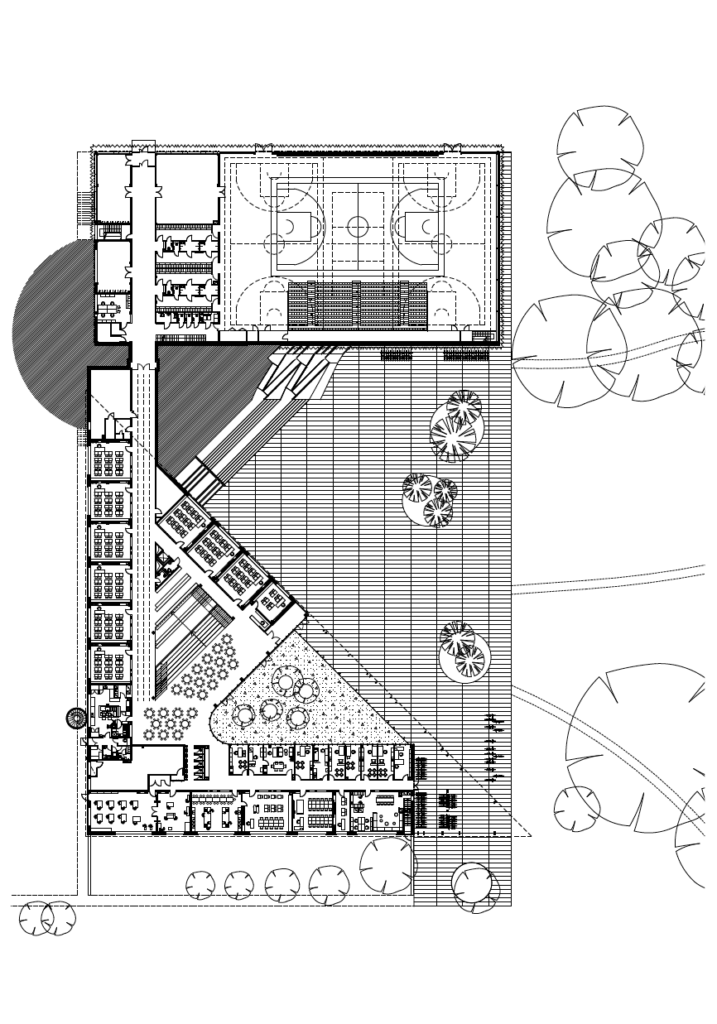

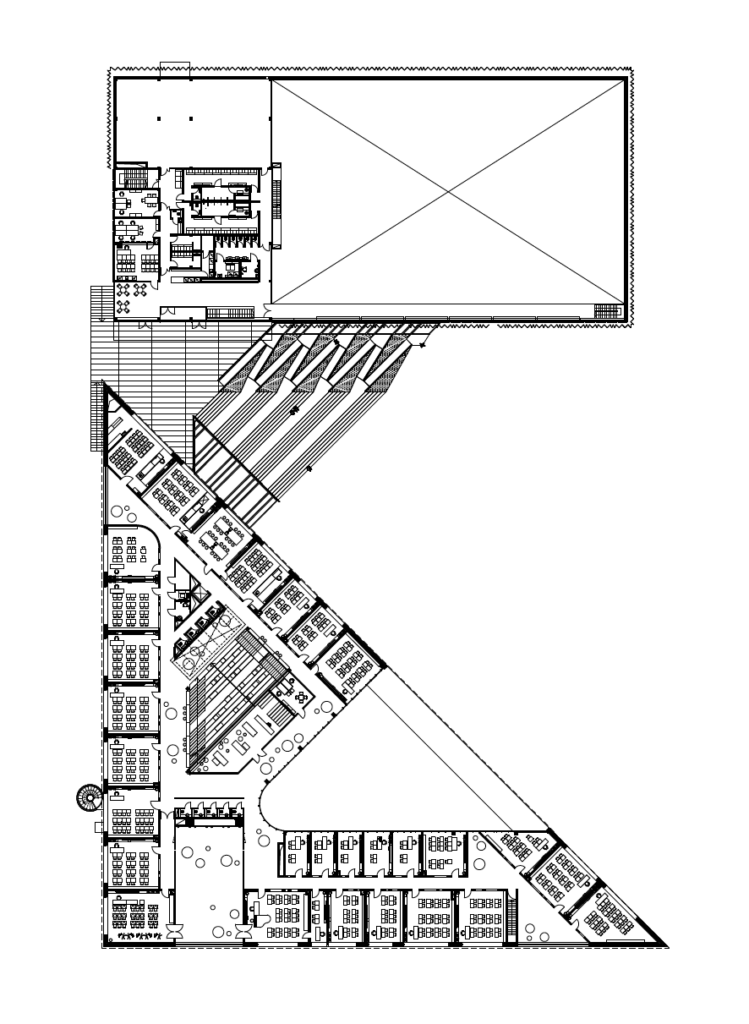

The site is composed of two volumes, reminiscent of the placement and orientation of the former school. The F. J. Wiedemanni street front is defined by the triangular school building with three facade and roof extensions that look like large screens turned toward the outside world, and an introverted cutout patio inside the plot. Together with the rectangular sports hall on the northern side, they form a large plaza that opens up toward the park in the east. The buildings are joined together by an outdoor slope with steps, ramps, and serpentine paths. The site layout takes into account the nearby verticals and accentuates viewpoints by introducing an axis between the old boiler house chimney and Türi Church, a significant landmark in the town. The plan, volumetric composition and wide glazing enable visual connectivity between the inside and outside by pointing out views of church tower and establishing visual relationships between school functions, the inner patio and surroundings.

The central plaza formed by the two buildings is rather representative—fit for formal events, but also for recreation. The underlying concept seems to focus on the diversity of space. Instead of being filled with installed special equipment, the open area is a flexible and inventive space, providing the freedom needed for games, physical activities, relaxation, and social gatherings.3 The paved schoolyard changes over into a lawn, and after two outdoor pavilions into a park, thus weaving school activities together with the nearby greenery. The overall scale of the complex is significantly larger than the established urban building fabric of the town. However, the orientation, volumetric layout, and exterior appearance help the buildings to blend in.

The upper part of exterior facades is clad in elegantly crisp white metal sheets. The school building has solid covering, whereas the sports hall is covered with an ethereal, transparent layer. On the ground floor level, the facade is covered with vertical coloured wooden slats. Use of a fresh green-yellow colour scheme and strips is common alse in the other examples of contemporary schools. Here it serves to fuse the buildings with the surroundings by visually dissolving the volume of the ground floor. During the dark hours of the day, the facade of the sports hall is lit up by colourful and gradient light hues, complementing the town’s neat appearance and idyllic atmosphere.

School as the world in a nutshell

One of the main goals for Karisma Architects was to create an inclusive spatial environment with a diverse mix of open and more private spaces that would support every child’s character and foster safe coexistence. Türi Middle School is designed to function as a city-in-miniature.4 The heart of the triangular building is a wide-stepped amphitheater. Such a common area strengthens the school community spirit and provides for flexible use of space. The school environment offers spatial solutions for socialising as well as withdrawing, and a variety of spatial situations for action and rest. Placing functions such as catering and cloakroom in the open common areas enhances socialisation and togetherness, but makes it necessary to find solutions for organising the circulation and flows, which became an important part of the design project.

The airy and sun-lit interiors feature wood carpentry and combine monochrome with calm but colourful accents in furniture and equipment. Classrooms of varying sizes (from 4 to 24 schoolchildren), workshops, and staff offices are placed along the outer perimeter on both floors, granting them direct sunlight and views outside. Classrooms are designed so as to best serve their primary function—concentration, teaching and learning. However, they are not enclosed bastions—glass walls extenuate any strong separation between classrooms and common space. Along with classrooms, the second floor accommodates also a library and assembly hall. Following the principles of universal design, the program also provides separate classrooms that enable a more individual approach for children with special needs.

The school building and sports hall are connected by an indoor running track with an integrated long-jump pit. Such unexpected features serve not only as a stimulus for physical activity and reference to a passion for athletic traditions, but also to blend the functionalities of physical activities and movement around the school. In order to support children’s micromobility, there is also a covered bike parking space. The sports building accommodates a large hall, full-scale gym, gymnastics rooms, weightrooms, and necessary service facilities. At the time of my visit, the hall was filled with daylight and occupied by children. An energetic crowd was following the dance routine of virtual dancers displayed on a screen. Speaking of technological advancements, the buildings feature an extensive green roof with solar energy panels, automatic sunshade and integrated energy-saving technologies such as automatic light dimmers.

School as a habit changer

Contemporary school design introduces new layouts, breaks preconceptions about the organisation of space (with gender-neutral bathroom facilities, cross-planning of seemingly separate functions, common spaces, etc), and encourages new practices that involve alterations by the users. Türi Middle School is a well-executed example of such design. While the main focus is on the well-being of children and their holistic social and experiential environment, the school is also a workplace for teachers and staff—their working conditions and sense of belonging to the community are likewise of crucial importance. So far, the architects and the municipality have received good feedback from both the direct users and the wider community.

Most architects would definitely agree that a successful project starts with a thoughtful brief and smart, proactive client. Asking the right questions and involving the future users is also very important. Architects of Türi complex have noted a tension between the principles of contemporary learning environments and national and European current regulations. It was a great challenge to implement new ideas in the framework of obsolete rules, but Türi seems to have greatly benefited from the resourcefulness of the municipality and assistance from the EAA in preparing the competition brief and evaluating the entries. This sets a good example of how to design a school fit for contemporary learners. In the end, though, I am left wondering whether such orderly modern-day school environments leave enough opportunities for children to make mistakes, encourage them to try out things, and allow them to be a little imperfect and rebellious at times.

DINA SUHANOVA is an architect, curator, and a researcher at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Design, and Architecture of the Art Academy of Latvia.

HEADER photo by Maris Tomba

PUBLISHED: Maja 106 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions

1 Herman Hertzberger, Space and Learning (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2008).

2 Kadri Klementi, Katrin Koov, Terje Ong, Muutuv kooliruum / The Changing Learning Space (Tallinn: Estonian Association of Architects, 2019/2021).

3 Kadri Klementi, Katrin Koov, Terje Ong, Muutuv kooliruum / The Changing Learning Space (Tallinn: Estonian Association of Architects, 2019/2021).

4 Herman Hertzberger, Space and Learning (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2008).