How should we understand age? Or old age? In some cases, it is perceived as a value—something good, like in wines that improve over time. Old cities and old works of architecture likewise comprise a number of values that new-made ones can lack, and even in people, it is generally taken to be a positive thing that they become wiser, more mature, and more experienced with age. At the same time, the thought of ageing is something that is feared and avoided if possible—‘Everyone wants to live long, no one wants to grow old’, says an Estonian proverb. In a society that is obsessed with youtg, old people are associated with problems and inconveniences. Old people need help—this is one of the common stereotypes that is often also amplified by the media. But most people do not know from their own experience what it is like to be old. Reaching old age can indeed be difficult, but conversely, it can also be carefree—each person ages in a different way. Some cheerful and vigorous elderly can be in a much better shape than people who are much younger. Thus, age is not a convincing argument that could say anything meaningful about the person and their abilities, skills or needs. And thus, we need to refute another stereotypical way of thinking—i.e., treating all older people as a uniform group. People whose age varies in the range of forty years cannot be measured against each other, just as we do not compare people aged 0 to 30. The group that is known as seniors (generally defined as people aged 65 or over) is a very diverse one in terms of abilities, interests, lifestyles, not to mention education, religion, nationality.

´Everyone wants to live long, no one wants to grow old´, says an Estonian proverb.

And yet, ageing brings about certain changes in functional as well as cognitive abilities, the most common one being reduced mobility. This is a natural part of life that should not turn seniors into a special target group. Normal changes that occur with ageing should simply be taken into account when designing living environments. If we want to approach urban planning and urban design in a human-centered way, we have to consider people’s abilities and needs, and since there is no such thing as the average person, it would be arbitrary and misleading to plan and design for such an entity. It is only logical that one takes cue from the demographic profile of a specific place. Population trends for Estonia indicate that we are a country with an ageing population. Take for example Tartu, which has the reputation of a youthful city—in 2023, at least 19% of the residents there were aged 65 or over. This is slightly less than in Estonia as a whole (20%); and yet, projections show that by 2050, the latter percentage will grow to almost 30%. It seems perfectly reasonable that these changes should be accompanied by changes in the design of physical space so as to anticipate a variety of problems that we ourselves might otherwise have to face in the future. For another Estonian proverb says: ‘What is put together by youth will be there for old age’.

Spatial design should aim for age neutrality, which is also declared in one way or another in several living environment design concepts. The most well-known ones are the initiative for age-friendly cities and communities from the World Health Organisation (WHO), and the ‘8 80 Cities’ idea that has been spreading also in Estonian architectural circles and focuses largely on the same principles as WHO. If the living environment has been designed in a way that suits both the young and the old, it generally tends to suit also everyone in-between and makes their lives better. We should design our living environment for all members of the society across the whole lifespan.

Age-friendly communities

WHO’s concept of age-friendly communities brings all fields of life comprehensively together and implies interdisciplinary and also cross-disciplinary collaboration. One of the main topics of this framework is the physical environment, which is closely linked to the subtopics of social environment as well as public services and information. Physical space is especially important, for by creating it you also create emotional and social environments that enable interpersonal association and interaction—in short, formation of communities. Social isolation and loneliness are by now a public health issue for both the young and the old. The extent of the problem and the need to facilitate social relationships among other things by the means of physical space are illustrated by studies showing that about 20% of Europe’s elderly experience social isolation, and that a lack of social relationships heavily affects the mortality rate. Conversely, by creating supportive and inclusive living environments, it is possible to support people in building and maintaining relationships (including meaningful ones).

International and Estonian guidance documents for age-friendliness:

Vision Document ‘Age Friendly Tartu 2030’ (commissioned by Tartu Municipality, produced by Civitta Eesti AS, 2021)

Umbrella terms ´indipendence´and ´accessibility´

In discussing the principles of age-friendly living environments, we should take note of certain fundamental concepts, and one of the most important ones is independence. Being independent concerns managing to live in one’s own home for as long as possible, use of spaces and services as well as availability of information. It is intertwined with social interaction as well as transport and mobility. Mobility and transport, especially public transport, play a significant role in supporting people’s independence. If people fail to adapt to some environment, they stay away; thus, environments should meet people’s needs so that everyone would have the opportunity to participate in the society. Planning age-friendly communities is a way of creating independence-conducive environments that follow the principles of universal or inclusive design.

Another important concept is accessibility. The concept of accessibility is so broad that it is necessary to specify what one means by it. Physical accessibility can be thought of in three categories. First, unobstructed physical access to and into some building—say, the availability of ramps instead of stairs. Second, accessibility in the sense of certain spaces or facilities existing at all—say, some indispensable footpath or even a single bench; a square, park or community centre. The necessity to have destinations is emphasised in gerontological literature. The possibility of going somewhere, being there and spending time is considered a very important component of high life quality. Once you create the opportunities, their use generally follows. Unfortunately, we do not know much about the preferred destinations of Estonia’s senior citizens—whether they have anywhere to go at all or where exactly they would like to spend their time. If you lack the knowledge, then you also lack the input that is necessary for taking such needs into account.

The third category of accessibility is the usability or quality of space. Danish architect Jan Gehl has aptly pointed out that the quality of a space can be measured in the time that is spent there—in those who stay. Thus, there is no point in installing seating if it is too low and difficult or even impossible to use, or renovating a town square if you need to climb stairs to get there, or building a public toilet if it is locked and the key is far away. The issues of accessibility should also be analysed in a broader context or in a journey-based way. The problems that affect older people’s access to public space often lie in seemingly small details such as the placement of handrails or benches. At the same time, it is also necessary to keep an eye on the big picture. The starting point in journey-based design is a person’s home, and thus, we should ask how seniors can independently exit their dwellings, move around, go somewhere and participate in social life. And—what can built environment professionals do to facilitate these activities?

Mobility-conducive space

The field of architecture tackles many complex and difficult issues at once. Some of these issues, especially when compared to the more global ones, might seem less important or even unattractive. This tends to apply to the design of age-friendly and inclusive environments, which seems to belong to the category of softer, more social and often minority-related topics. And yet, it has a central role in maintaining public health—physical and public space affects both physical and mental health. Following the principle of ‘health in all policies’, assessing people’s health and the impacts on it should be one of the main tools in making spatial decisions.

Spaces that are conducive to physical activity and mobility are probably among the biggest contributors to healthy ageing and also an indirect way of saving healthcare costs. Thus, key components of public space need to emphasise walkability, a prerequisite of which is the availability of high-quality pedestrian roads. Bumps, soft materials, excessive gaps and slopes can affect one’s balance and increase the risk of falling, the latter being one of the leading external causes of mortality among the elderly. Walking is seen as important for preventing falls and increasing physical fitness when having an otherwise sedentary lifestyle.

Mobility is also directly related to the need for both indoor and outdoor resting facilities; furthermore, longer distances could encourage more movement, and if there are sufficient opportunities to rest, then the distance between the destinations does not matter much for accessibility. One needs to consider the particular context and keep in mind that there is no universal formula for calculating distances. There are, however, the ergonomic parameters of benches, although here one could again argue that they are based on the average person. Although walking is the only form of physical activity for many elderly (hence the importance of walking paths), activity can be promoted also by creating bicycle paths and public sporting grounds, not to mention other destinations such as community gardens that draw people out of their homes.

Physical and public space affects both physical and mental health.

In sum, an age-friendly living environment enables people to get by independently, promotes physical health and active mobility as well as mental health and well-being through social interaction, a sense of belonging, participation in the society, and mitigating loneliness and social isolation. It is a living environment that makes us feel needed and welcome, and a good place where to grow old.

The field of spatial design has a great role and responsibility in taking care of people’s health by understanding their needs and translating them into spatial language. One of the goals in the ‘Estonia 2035’ strategy is a safe and high-quality living environment that takes into account the needs of all its inhabitants. The basic principles of high-quality space likewise involve aiming for safety and health, accessibility and social cohesion. These aims are also present in the development plans of municipalities. Bringing all these theoretical ideas to life does not come about in tempo allegro—changes in physical space often take a long time. However, adopting that way of thinking and acknowledging people’s needs are something that can be done right now. The main thing is to not get tired and keep moving towards the destination that would enable us, once we are old, chuckle contentedly as we take our walks with our peers and check whether there is any moss growing on us.

SIRLE SALMISTU is a senior lecturer at TalTech Tartu College and a researcher. She also works as a landscape architect and urban planner.

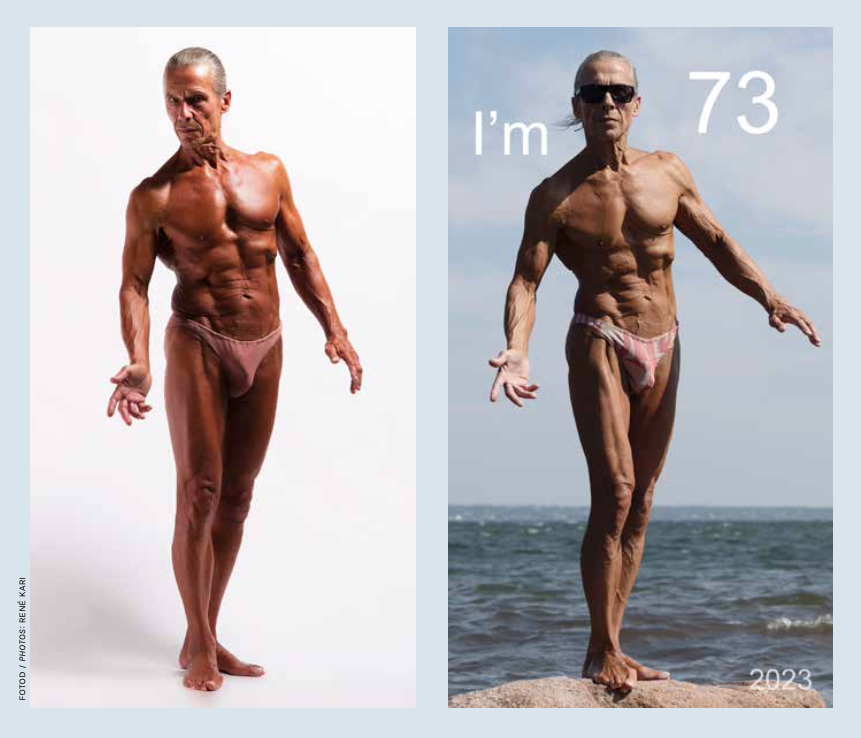

HEADER: René Kari ‘The Body as a Work of Art’

In 1974, the then 24-year-old artist René Kari decided to shape his body to resemble an antique sculpture with the goal of reaching his top form by the age of 57. Every year since 2004, he has recorded the current state of his body in photographs to confirm that the guiding principle of the project ‘looking better every year’ is still working and that the refining of his body as sculpture is ongoing. The process in question can also be seen as anthropological research—how long is it possible to look better with each year? How much longer can one look better at age 70+ than when one was 30, 40 or 50 years younger?

PUBLISHED: MAJA 2-2024 (116) with main topic OLD AGE

1 „Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities“, WHO veebileht, https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/

2 Veebileht „8 80 Cities“, https://www.880cities.org/

3 Rose Gilroy, Planning for an ageing society (Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 2021)

4 „Promoting Health in All Policies and intersectoral action

capacities“, WHO veebileht, https://www.who.int/activities/ promoting-health-in-all-policies-and-intersectoral-action-capacities

5 Sirle Salmistu, Zenia Kotval, „Spatial interventions and built environment features in developing age-friendly communities from the perspective of urban planning and design“, Cities 141 (2023): 104417