The most important question regarding the future Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel is no longer if, but how. What kind of unified twin city will Tallinn and Helsinki become thanks to this fast link? This requires foresight and awareness from officials, professionals and politicians.

The Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel, which is planned for completion by 2038, is clearly the temporal, logistical and spatial change of the century in this region. Together with Rail Baltica, it will significantly change the area. In order to ensure that the effects following the change in perceptible urban space don’t run their own course, now is the last chance to start spatially designing the Estonian capital and the country as a whole in a way that takes the forecasts into consideration.

How could the city of Tallinn develop spatially and where should the main station for the Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel be built? This is the number one discussion point for public debate. This debate should be based on the public interest and rely on long-term and well-considered urban space analysis performed by professionals. At the beginning of the decision-making process, apart from economic and other effects, the spatial consequences must be recognised aswell. A fast link between Tallinn and Helsinki that creates a new competitive conurbation in Europe with 4 million inhabitants1 is not the Haabersti roundabout, Reidi Road or Tallinn-Tartu highway. It is a matter on a completely different scale. There is no national or even regional precedent. It is a great opportunity, and the stakes are high.

The future belongs to conurbation

Cities and conurbations, which act as strong and diverse centres, are becoming more important in the world than nation states. In today’s Europe, it goes without saying that wider economic and social success is centred on urban networks.There is strong competition between such regions, which in turn form specialised but cooperative cities.2 Cross-border regions similar to Tallinn and Helsinki are Öresund (Malmö in Sweden and Copenhagen in Denmark) and Centrope (Vienna in Austria, Bratislava in Slovakia and the southern regions of the Czech Republic). Within city regions, inhabitants move constantly between work and home. Annually, cross-border pendulum migration between the city regions is added to this. Companies are moving flexibly from one country to another, searching for short-term commercial advantages in different city regions. The production and consumption chains of products and services are becoming more multi- and transnational.

The long coming of the tunnel

The idea of connecting Tallinn and Helsinki has a long history. Finnish geologists, headed by the City of Helsinki’s geology department under Usko Anttikoski, presented a constructional engineering analysis of a Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel in 1992. In Estonia, which had just regained its independence, the idea was not taken very seriously. Several other studies were conducted by Finnish specialists, and a study concerning geological aspects will be completed in 2018. Interest has also increased in Estonia. A noticeable upturn has taken place in the last decade concerning tunnel construction analysis. For now, let us look at but a brief overview.

In 2008, the City of Helsinki’s geology department compiled a profitability study on a railway tunnel under the Gulf of Finland. The ground has since been studied in relation to the tunnel by the Geological Survey of Estonia (2010 and 2012). The Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel’s ground and bedrock construction terms and conditions were issued in 2012, comprising a geological database for the possible area of the tunnel. In 2008, the Helsinki-Tallinn Feasibility Study Working Group was created based on a meeting of the mayors of both cities. In 2010, the European-level Euregio Helsinki Tallinn Transport and Planning Scenarios Project (HTTransPlan), which explores the economic impact, was born. In 2015, the Tallinn-Helsinki fixed link was presented, which is a report including the profitability of execution and several other topics. It was ordered by Helsinki, Tallinn and Harju County. In addition, several articles have explored social, economic and public impact, for instance a publication issued in 2010 by Demos in Helsinki which collates people’s opinions. There are also reports concerning the development of the OECD region and academic works. In 2016, Harju County Government, Helsinki-Uusimaa town council, the Finnish Transportation and Communication Ministry, the Estonian Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communication and the city governments of Tallinn and Helsinki jointly signed a memorandum for a Tallinn-Helsinki transport connection. In February 2017, additional studies were commissioned with the help of the European Union. Ramboll Finland, Sito, Strafica, Kaupunkitutkimus HE and Pöyry Finland3 are comparing the construction costs and efficiency of marine traffic and the tunnel. Three limited liability companies – Sweco, WSP and Swiss Amberg Engineering – are currently investigating construction technology options and the financial meaning of building and maintaining the tunnel. They are also analysing the tunnel’s route corridor and considering safety issues. The results of the two latter approaches should be made public within a year.

In addition, the fast link of the two cities was also discussed at the transportation and energy meeting of the Finnish and Estonian Prime Ministers in 2016. The Estonian side was interested in involving Finland as a financier in building Rail Baltica. The Finnish side showed an interest, but only if the fast link tunnel between Tallinn and Helsinki is also built. The biggest target market for the Finnish economy’s exports is Germany, surpassing Sweden and Russia.4 It is clear that Finland is interested in participating in a project that connects their product flow via a tunnel and Rail Baltica to Central Europe.

It is worth mentioning that the connection between Tallinn and Helsinki was selected as one of the nine finalists in Hyperloop One in 2017. These nine were considered to be the most attractive by the Hyperloop jury and probably also the connections most likely to be built. Hyperloop and other similar technological proposals can be considered when the technical solutions for the tunnel and trains are selected.

Who designs Tallinn and Harju County spatially?

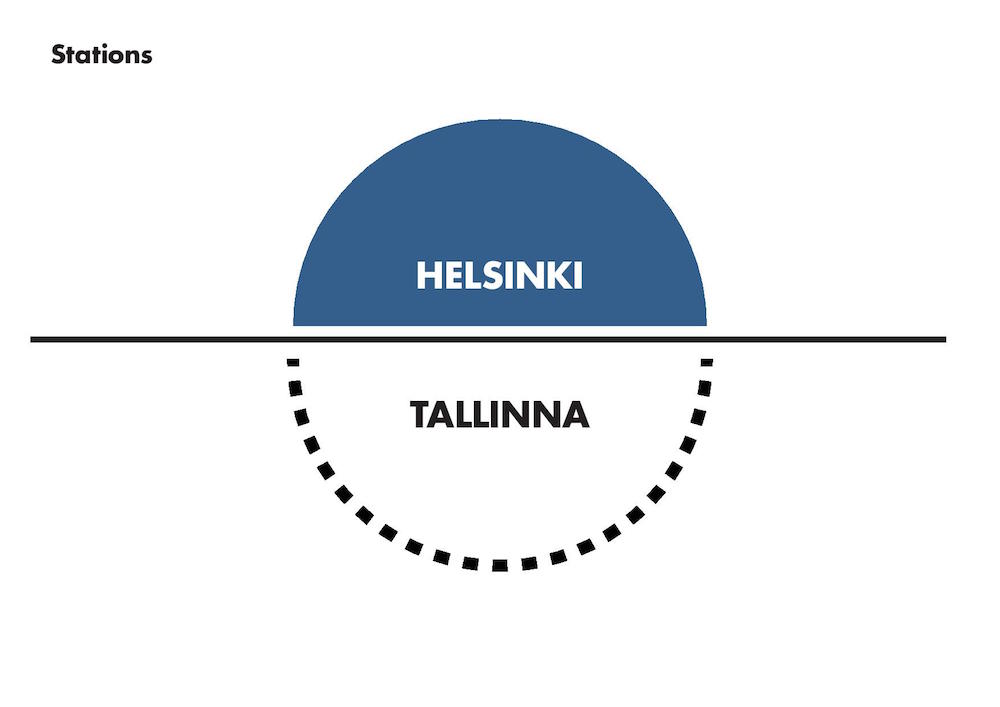

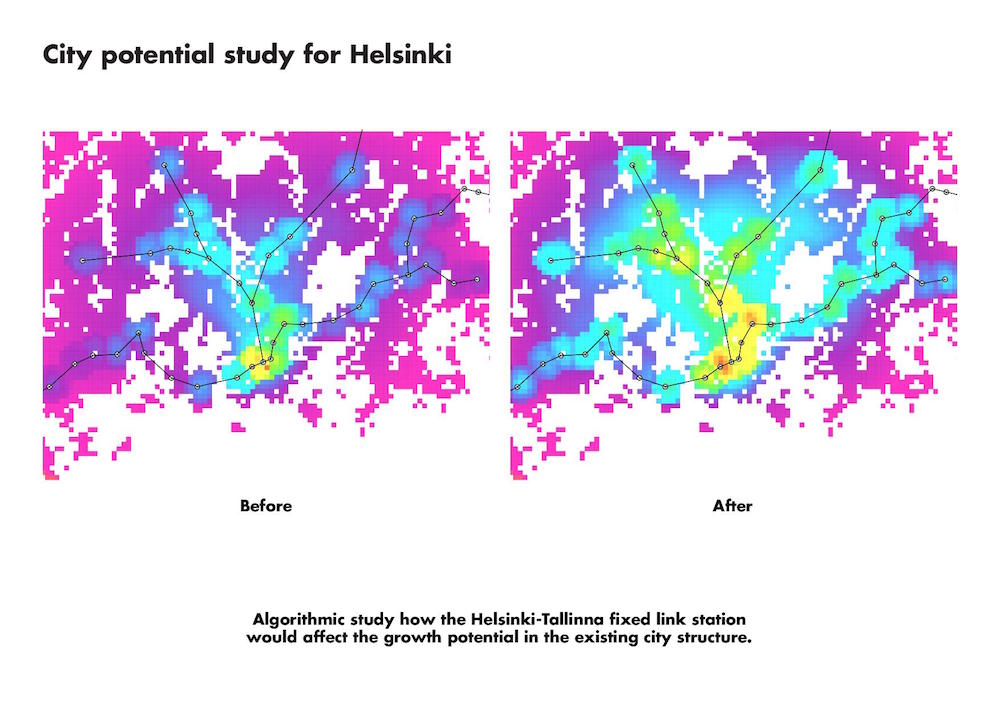

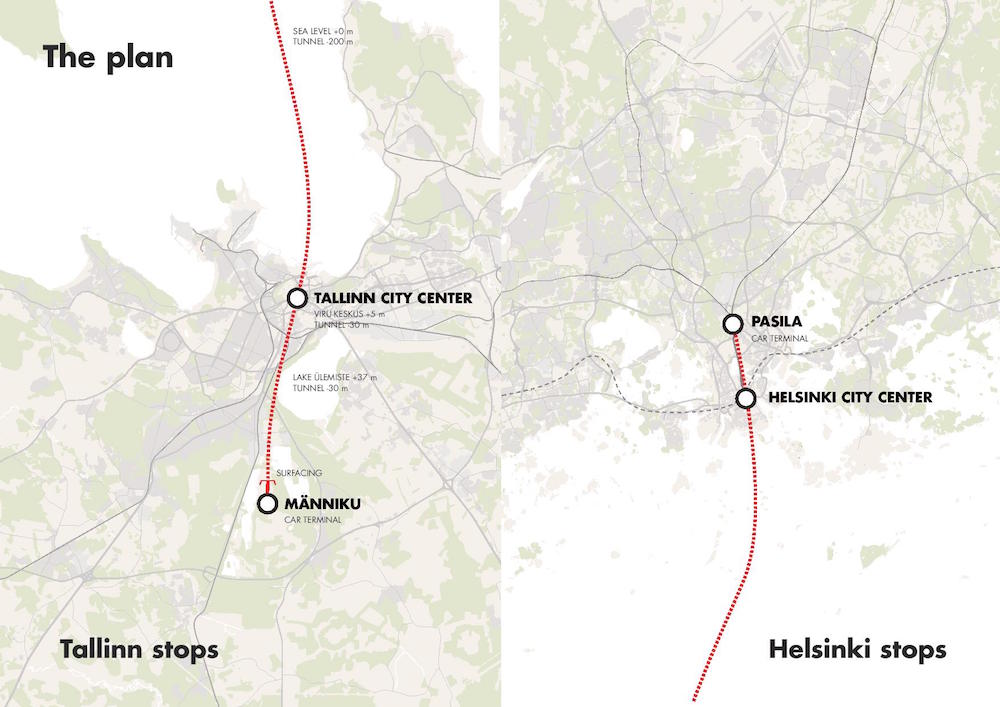

The aforementioned studies are conspicuous for not focussing on the analysis concerning the effect of spatial changes in Tallinn and Helsinki. Urban design on the two sides of the Gulf of Finland is very different. Since a major part of the land in Finland is owned by local governments (for example, the City of Helsinki owns around 80% of the Helsinki city area), most planning is done in Finnish urban design departments based on the city’s visions and application plans. In Helsinki, the main station is planned to be built in Pasila, which is well connected to the public transport network. But who will design and monitor the process daily in Tallinn and Harju County? How will the tunnel’s location and its potential, changes and developments be analysed and planned on this side of the gulf?

Movement on two shores

Clearly a fast link means a totally different twin city. We can learn from the example of Malmö and Copenhagen where people’s movement patterns and choice of living space changed drastically. It is estimated that around 60,000 Estonians work in Finland and often go home for the weekend.5 The new fast link would be attractive to these people, since they wouldn’t have to go home for the weekend anymore: their homes could be on the other side of the gulf, as driving to work would take about half an hour plus the time spent on public transport. The workforce is predominantly moving from Tallinn and Harju County to Helsinki and Uusimaa, but the flow of money from the tourism sector is about three times higher from Helsinki and Uusimaa to Tallinn and Harju County.6

The flow of passengers keeps increasing at the Port of Tallinn: In 2015, 8 million trips were counted at the Port of Tallinn; in 2016, this figure was already 10 million. 11.5 million trips were made from the Port of Helsinki in the same year. According to study forecasts, marine traffic will probably not disappear between the two cities after the tunnel has been built, but it is estimated that 11 million trips will be made annually via the tunnel by 2042, with 25,000 people passing through it daily. How will the tunnel operate in connection to public transport on both sides of the Gulf of Finland? If the fast link between the two cities takes only half an hour, this means that further transportation must be quick and effective.

Is Ülemiste the best spot for the main station?

One of the trickiest questions in Tallinn is the location of the main passenger station. Some claim that the location should be near the Rail Baltica station at Ülemiste. We should ask what kind of citywide or nationwide spatial analysis showed that the main station of Rail Baltica and perhaps the new tunnel should be located at Ülemiste in the first place. Which analysis explores the effect this kind of decision will have on Tallinn? What kind of public discussions were held at the social level and with architects?

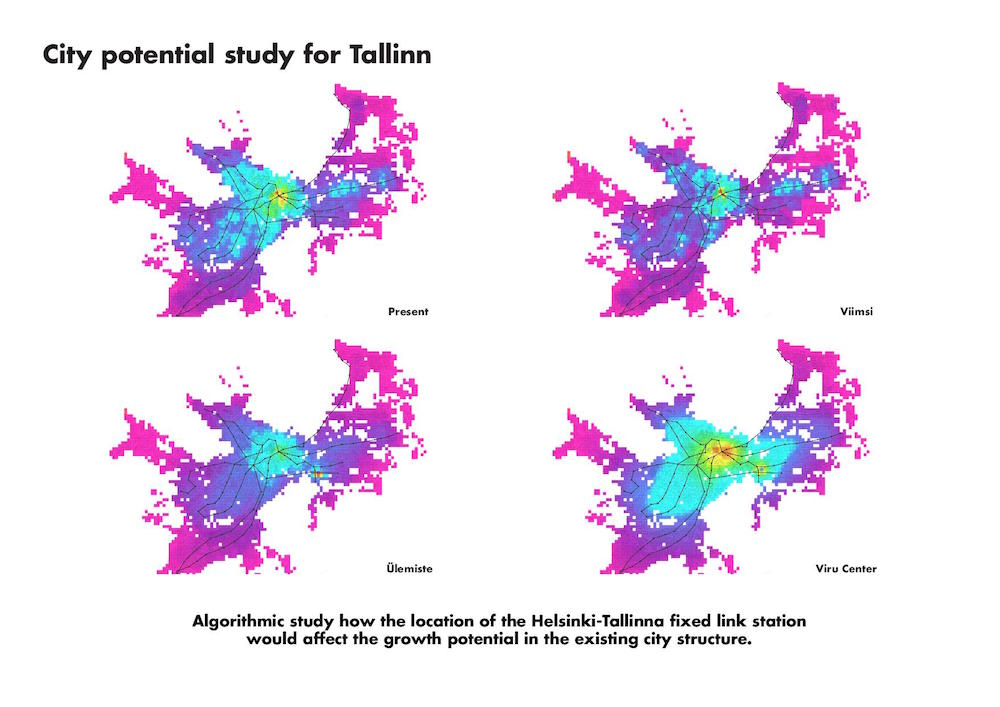

Professional skills and the ability to visualise allow architects and urban planners to foresee the spatial scenarios of the future twin city. In September 2015, members of the Estonian Association of Architects and the collective body of Finnish architects Uusi Kaupunki organised a workshop at which they visualised how the planned fast link between Tallinn and Helsinki will influence urban space in Tallinn. Over a couple of days, the teams from both countries developed five solutions as to how the Tallinn side would look and operate.

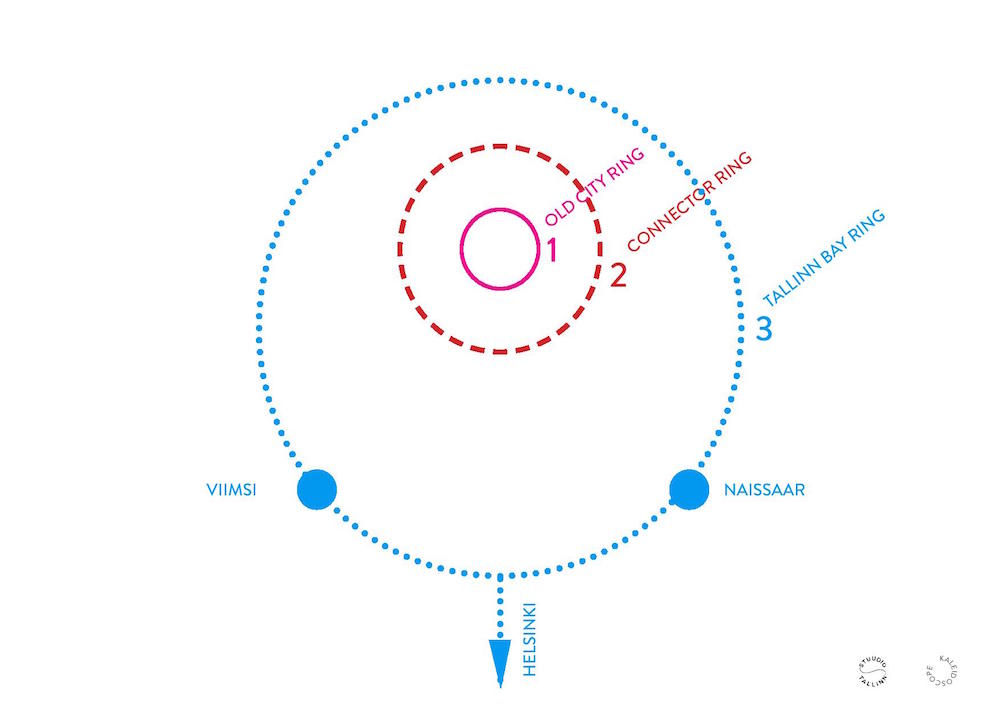

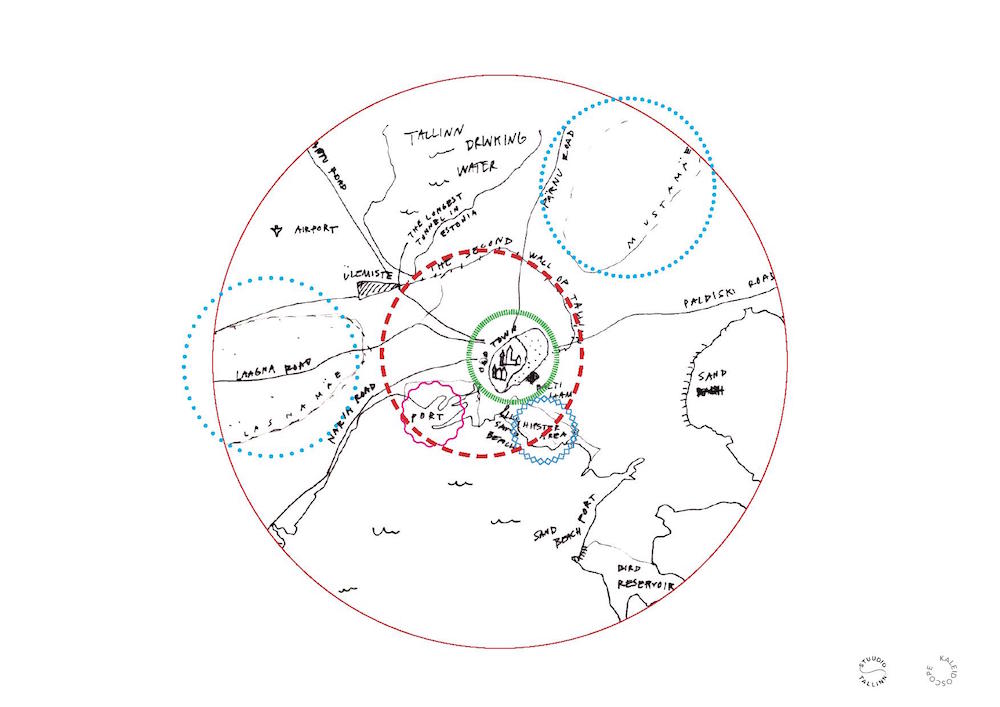

Stuudio Tallinn (EST) and Kaleidoscope (FIN) explored the most reasonable way to connect the tunnel to the so-called three circles surrounding the Old Town of Tallinn’s infrastructure. They recommended a connection that would be fast, yet attractive. If the tunnel emerged from the ground on the island of Naissaar and were connected to the city centre by a bridge, people could enjoy the sun, sea and Tallinn’s famous silhouette. Arriving in Tallinn with an experience that emphasises the city’s identity would be the key to the two cities preserving their uniqueness as a twin city. According to the authors, the centre of Tallinn has relatively few inhabitants, yet a lot of free land for future living spaces. It would not be wise to flow into business areas, so the tunnel should be connected to the city centre relatively smoothly via the existing tram network.

The vision of the architecture office Pluss (EST) and Futudesign (FIN) recognised that the most logical option would be to establish the passenger station in the city centre, in Tammsaare Park or near Viru Keskus shopping centre, where all of the important transport routes connect; also, most public institutions, meeting places, universities, etc. are located in the city centre. Locating the tunnel in the city centre would be convenient and quick for the inhabitants of Tallinn and it would operate like a subway.

The team of Yoko Alender, Raul Kalvo (EST) and Studio Puisto (FIN) offered answers to questions concerning where the additional population would live in Tallinn and what kind of living environment would meet the expectations of the twin city’s inhabitants. The inhabitants of the twin city would prefer to live in areas that are well connected with public transport, where a student, a professional or a senior citizen could choose an apartment or a room that would satisfy their needs and where auxiliary rooms and services are shared.

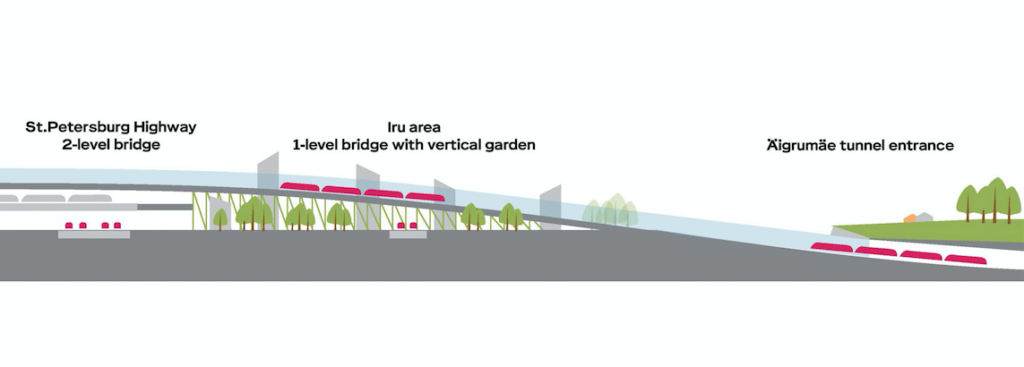

Novarc Group (EST) and Architects Rudanko + Kankkunen (FIN) explored the previously considered locating of the tunnel in Viimsi. The team proposed raising the part following the tunnel’s mouth up above the living areas and roads and designing the tunnel’s pipes with vertical fences as a futuristic sight. Building the tunnel in Viimsi has largely been the initiative of Viimsi itself. The team’s architects went to a lot of effort to make the tunnel’s opening even a little bit more human. Obviously, Viimsi’s solution would be very complex and would require an even longer underground railway tunnel or more likely a railway (tunnel) in air supported with pillars that would connect Viimsi to the city centre along the east side of Tallinn (near the St Petersburg highway).

Sweco Projekt (EST) and LUO Architects (FIN) observed the Ülemiste terminal and future prospects surrounding the area. Ülemiste is a car-focussed area of supermarkets and multi-level intersections. In order to create a decent public space and urban environment there, the environment must be changed completely. The leaders of the Ülemiste option would like to link the terminals of the tunnel and Rail Baltica to the area of the airport. This is understandable. But movement of people would be more efficient if the tunnel were connected to the public transport network as a subway in the centre, not at the final destination.

The development of cities is a slow process and the tunnel is estimated to be completed in 20 years’ time. This gives enough time for urban planning visions to make an impact. Involving architects as specialists in the field, but also the initiative of people in the field, is very important so that the infrastructure objects are successful. The operating of cities involves the logistics of large masses and products. However, a pleasant environment is what makes a city worth living in and visiting for both locals and tourists.

AET ADER is an architect and the vice-president of the Estonian Association of Architects. She graduated from the Estonian Academy of Arts, where she studied architecture and urban planning. She has also studied in Copenhagen. Aet works at the architecture firm b210, curated the Tallinn architecture biennial “Recycling Socialism” in 2013, was one of the editors of the magazine Ehituskunst and teaches at the Estonian Academy of Arts in the departments of architecture and interior design.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2017 autumn edition (91) with main topic Shared Space

1 About 4 million people live within a 200-kilometre radius of the twin city.

2 Jauhiainen, Jussi S. “Urban networks between Tallinn and Helsinki – Talsinki or Hellinn?” 2004, http://www.solness.ee/maja/?mid=134&id=331

3 https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-9457227

4 https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-9272530

5 https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-8569503

6 Economic flows between Helsinki Uusimaa and Tallinn Harju region, HTTransPlan, Seppo Laakso & Eeva Kostiainen, Kaupunkitutkimus TA Oy, Tarmo Kalvet & Keio Velström, Ragnar Nurkse School of Innovation and Governance, Tallinn University of Technology, 2013