BARGE YARD

Location: Ujula 98, Tartu

Architecture and interior architecture: Maarja Kask, Ralf Lõoke, Ragnar Põllukivi, Martin McLean, Marja Viltrop / Salto

Client: Tartu City Government

Construction: Ehitustrust

Total area: 1500m2

Competition: 2009

Design: 2016-2019

Completed: 2020

The buildings of Barge Yard wish not to reduce to inconspicuousness or to gently stroke the viewer’s gaze; they have a much broader agenda—to stand behind creative values even after solving the maze of practical questions.

Completed in autumn 2020, the Barge Yard is a structure that from a distance strikes the viewer as good architecture—it is abstract, slightly mysterious, well located. It is one of those success stories that has an unexpectedly long genesis—nearly fifteen years of leadership and discussions drawn out under the auspices of the Emajõe Barge Society as well as Tartu City Government. There was nothing after which to model the vision, either—no example to draw from on how to revive barge traffic on the Emajõgi River. Construction of the first hanseatic sailing barge began in 2004 in a shed made of crafty construction film and glued timber, located at the current location of the Barge Yard. The enterprise gathered momentum and more opportunities were found to build a bigger complex. The winds of change of the noughties and tennies brought several projects of which the 2016 design by Salto ended up being built.

What is the communal space of the 21st century like?

The Barge Society that manages the Barge Yard was founded in 2004 by a group of friends involved in building traditional watercrafts for inland water traffic, developing nature-friendly tourism and enlivening historical waterways. Other communal values such as sustainable ways of living, introducing traditional culture and shared activities are part of the pursuit. The Barge Society has strongly influenced Tartu, coming across as citizen activism that epitomises the spirit of the city. The relationship between the Emajõgi and Tartu has for long been rather distant—the river has been separated from the city and confined into a concrete bed, leaving the recreational potential of the waterbody in a clearly underused state—most residents have been left with nothing more than the pleasure of gazing it. A jovial story among the members of the Barge Society describes how a former mayor of Tartu had to ponder for quite some time to figure out which direction the river flows in. In many ways, the society’s contribution to Tartu has been in returning the Emajõgi to the city, however strange that may sound. The inclusive budget of Tartu along with various river-related proposals have attempted to stitch together the river with grand and credible activities. It turns out the number of European cities where river water in the urban centre is sufficiently clean for human contact and bathing is unexpectedly low.

In 2014, by the somewhat derelict Kalevipoja park, the Barge Society designed a meeting place on the oldest inland water vessel, the hundred-year-old dredger Peipsi 1, and baptised it the Inland Waters Embassy. The embassy represents community architecture as we have come to best understand it in the 21st century—informal, non-aesthetic, robustly or smartly simple, extremely well relatable to the surrounding environment, and equipped with uncannily sound spatial phenomenology. All these properties also characterise the Inland Waters Embassy designed by the Barge Society. As we well know, the community low-aesthetic is in a nerve-rackingly close and flirtatious affiliation with the aesthetics of ugliness, whose appropriateness in Tartu city centre prompted ardent feedback in both the city government and the residents. Before the administrative reforms, waterways were owned by the state, thus the Inland Waters Embassy was under state protection and remained out of reach for municipal powers. With regard to unexpected change, a situation like that inspires the question that perhaps decision-making at the local government level is not necessarily the only right way to steer towards when wanting to solve matters? Largely due to the constructive nature of their self-expression, the Barge Society had thus created their own (non-)aesthetic signature. Against this backdrop, it was fascinating to see how the vigorous, minimal, seemingly diametrically opposing aesthetic signature that Salto is known for would flow in the design process of the Barge Yard. How would this aesthetic chasm be met and how would the community settle in a space that has been created by ambitious professionals?

Ensemble houses

One of Salto’s clever architectural moves that instantly grants their designs a stronger air of ambition and much creative vigour is their well-orchestrated aggregate approach to housing. This knack is enforced by the unconventional shape of the buildings—Saltoean geometry detaches from the archetypal roof-wall logic so that their design objects are something in between a building and a sculpture, and on their way of becoming sculpture they become charged as objects of art. Sculptural assemblages can be found in the four cylindrical apartment houses in Tartu Riga Quarter (2014–2023) and the four-volume apartment building in Viljandi (2016–2017). The Barge Yard with a vast array of functions, communal content and a riverside location is gratifying subject matter for such an ensemble-like approach.

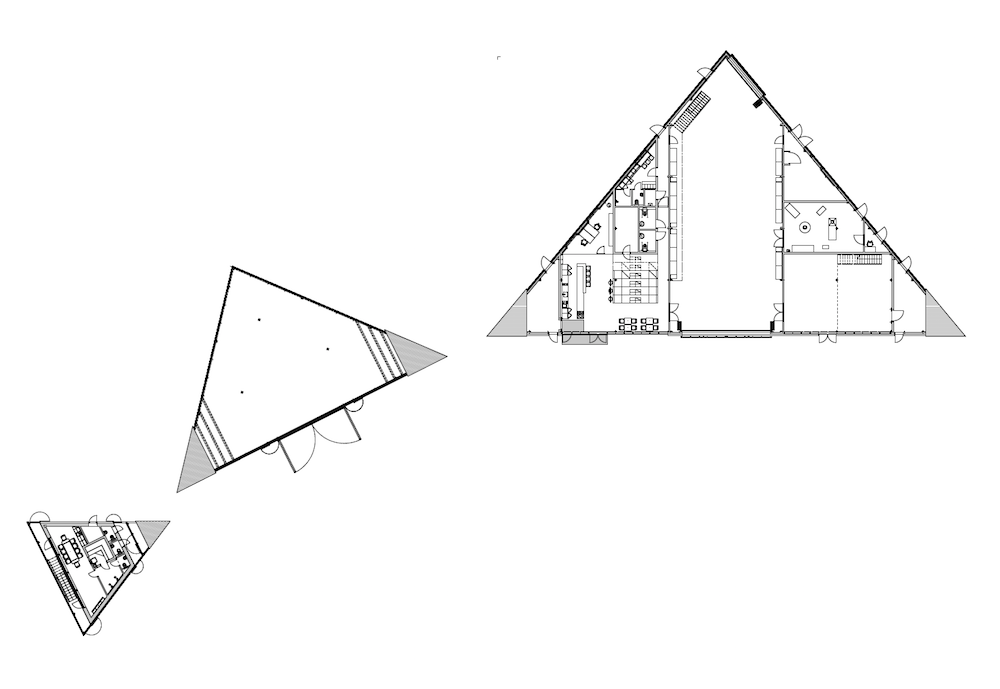

Three polyhedric buildings with triangular facets accommodate rather different functions and form a cosy courtyard by the former Matteus’ outdoor swimming pool on the riverbank where it is easy to imagine summery activities and an outdoor cafeteria with a touch of Berlinean effortlessness. The visitors’ centre in the main building offers views of the construction process of a new sailing barge nearly 30 metres in length, and spaces for arranging workshops, enjoying the riverside cafe, screening films and organising group discussions. The building has attractive, varied internal views that are by no means predictable; the windows on the exterior facade with a Kubrickesque monolithic feel remain almost invisible which makes the abundant flow of natural light from unexpected places all the more surprising and regulates the amount of illumination so as to emphasise spatial depth and sustain obscurity where necessary: the whole holds together well and induces a stimulating spatial experience. The middle polyhedric volume is a shed with dimensions befitting a winter abode for a barge. It is currently showing a rather unique object—the fragments of the only wrecked barge known to still exist that recently washed up on the shores of Lake Peipus. The volume closest to the river houses a sauna and also shelters the coastguard, whose existence as an actual user seems to have been left out in the design phase.

The exact layout of the workshop complex creates ambivalent feelings—the unforced and organic arrangement of the volumes seems fine, but the barge yard seems rather indifferent positioned next to one of the most popular beaches in Tartu. While there are no structures that need relating to in the immediate vicinity, the charge of the surrounding landscape begs the question if the project could have been more precise in relation to the landscape, and seek common ground?

Fish with legs

The architectural feat and a most telling feature about the Barge Yard consists in how the buildings do not really reamind buildings. They rather look like natural formations—it could be a boulder field that found itself at the bottom of the Emajõgi primeval valley, carried there by post-glacial meltwater. One thing is for certain—Salto Architects never had anything like that in mind, but in an unexpected way the volumes of the barge yard link with the obscure phenomenology of the Emajõgi that mystified and personified the river in the textual culture of Tartu in the noughties and tennies. This delicate and unusual alertness is privy to manifestations of mostly capitalistic tendencies of the comfort culture in contemporary spatial design where architecture caves in, ceases to be spatial art and attempts to grant wishes, so it would be better to renounce it entirely. The Barge Yard does none of those things. These primitive forms are neither following the design hype or like-culture nor promising to heal or bless anyone. Their effect is as orphic-primordial as the antecedent textual studies—they are like a Devonian fish with legs that has dashed out of the sandstone outcrop behind the barge yard—completely quaint, but for their own reasons, completely memorable, completely (Non-)Tartu. The architects can certainly be recognised for their congeniality in catching the avantgarde subtides of Tartu. The connections to dignified robustness and a discernible temporal dimension which the buildings evoke attest to the story of the barges themselves. When these trade and freight vessels appeared on our inland waterways along with the Hanseatic League, they epitomised the ‘high technology’ of their time. Born optimal, they did not undergo much change over time which in the years preceding WWII caused them to go obsolete as true maritime dinosaurs.

Architecture as a form of resistance

The air of the complex is that of a finished, architecturally exquisite visitors’ centre, although the communal, evolving nature of the barge society and their unique building work is presently not apparent. No doubt, the fact that the complex was, in a way, and in a way, was not designed for the barge society, plays a role here. Although much of the input in the brief came from the Barge Society, the project was commissioned by Tartu City Government and the Barge Society acts as a mere tenant; properties aren’t usually tailored to individual tenants. Back to the question of community architecture—if professionals are involved in a project, can there be room left for things like community dynamism and precise locality? When visiting the barge yard, I am struck by its architectural and enigmatic atmosphere which is something to rejoice over without hesitation. At the same time, there is a perceivable architectural autonomy, perhaps even introversion in the air—there is no hand held out for the user to grasp and the building prefers to remain a thing in and of itself, cryptic. During my time of visiting the yard, a barge built with fir garlands stood in the courtyard, nearby were a few more soviet-era riverboats, waiting to be rescued from their demise. A view like that creates a certain visual dissonance between the buildings and the water vessels, a type of shift where the architecture in its forcefulness begins to emanate as a form of resistance. A form of resistance which, despite capitulation to economic and capitalistic pursuits in the construction sphere, reminds us of a culture where we are ultimately steered by a conundrum, not a solution.

Salto’s form signature seems to have become more laconic over the years—for example, the flickering and fluctuating lines that we saw in the Estonian Road Museum and the Sõmeru Community Centre have become less apparent; supposedly this should draw attention from play with architectural form to other issues. But which ones? Paradoxically, the answer is: back to the form, yet this time not to the innocent frolic of a sovereign architectural line, but a rather powerful instatement, a standpoint, a political act. These buildings wish not to reduce to inconspicuousness or to gently stroke the viewer’s gaze; they have a much broader agenda—to stand behind creative values even after solving the maze of practical questions. The form of Salto’s buildings has simplified to a critical limit before becoming trivial, and through this discernible criticality and tension they refer by proxy to the pressure points of contemporary (construction) culture, which consist in its generic, commercial, materialistic, and simplistic attributes.

It seems this aesthetical abyss between Salto’s signature and the barge community will remain, but its very existence and daily atonement by the use of the barge yard is a pure part of life—it steers away from comfort zones, cracks open a broad sensory scale, keeps the mind in focus, and creates unplanned opportunities. Now, all that is left is to trust the perpetual cleverness of the Barge Society to use simple tactics to domestisise the indoors and outdoors of the barge yard and add something in the spatial phenomenological plane which they managed so well with the Inland Waters Embassy and which may only be granted by the everyday user. The difference is that this time, they are backed by powerfully charged architecture.

KAJA PAE is an architect and physicist, Editor-in-Chief of Maja (2017-2022)

HEADER photo by Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 104 (spring 2021) with main topic What’s happening?