A. M. LUTHER MACHINE ROOM

Architecture and design of the public and office area: Hanno Grossschmidt, Tomomi Hayashi, Liis Voksepp, Marianna Zvereva, Anna Endrikson, Jüri Nigulas, Andres Ristov, Sander Treijar (Hayashi-Grossschmidt Architecture)

Engineering: Maari Idnurm, Merith Auksmann, Eerik Kask (Ekspertiis and Projekt)

Interior architecture of the cafeteria, exhibition and sitting areas: Tamme (Kadri Tamme Interior Architecture)

Interior architecture of Äripäev office: Kääramees, Illimar Truverk, Tiiu Saal, Kaur Käärma (Arhitekt11)

Commissioned by: Lutheri Ärimaja

Constructor: Nordecon

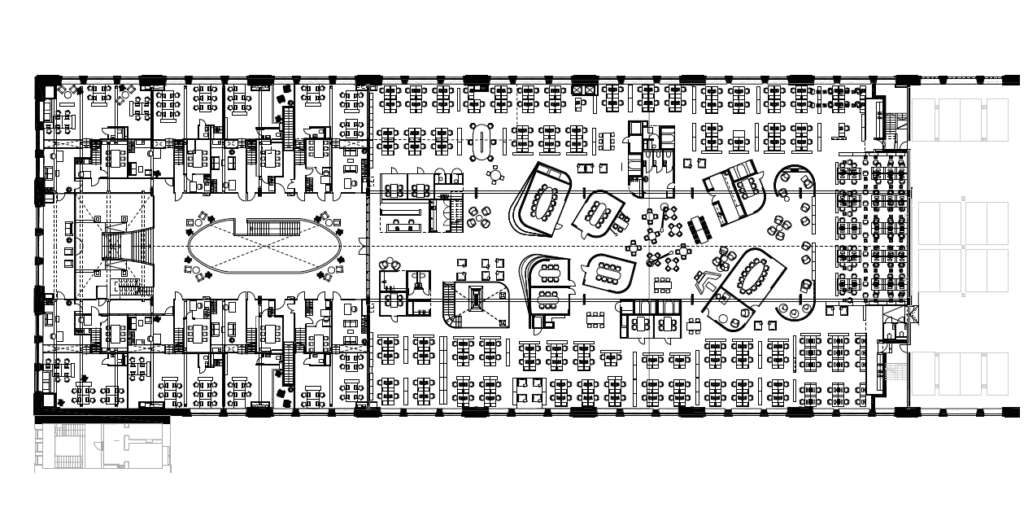

Building area: 4 147 m²

Closed net surface: 6 520 m²

Design and construction: 2015–2017

Strict special conditions set by the National Heritage Board have ensured excellent renovation results but not the thunderbolt contemporary solution on a par with the original.

The industrial architecture built in late 19th and early 20th century has today become the symbol of modernism. The building complexes with utilitarian functions combined industrial rationality with the romantic notion of progress. The aspirations of the era were expressed in fashionable shapes and materials. Reinforced concrete was novel material in Estonian context and allowed them to design more expansive and brighter spaces both accommodating the machinery and providing better work conditions.

The new reinforced concrete production facilities – machine room and furniture manufacturing premises – of A. M. Luther factory designed by Nikolai Vasilyev and Aleksey Bubyr from St Petersburg were completed in 1912. It was not the first cooperation between the plywood furniture manufacturers and architects, as a few years earlier, they had completed a three-storey Art Nouveau villa for Luther family (today known as the marriage registry office “Palace of Happiness”). The distance between the two buildings is practically non-existent and the proximity of the factory owner’s summer villa to the production facilities may be considered as a reflection of the ideal of the rationality and speed of the modern society. Today, several European cities have come to integrate less complex manufacturing functions into the urban space in order to avoid the forced daily commute between work and home.

The strive for a new and better future may be perceived also in the basilica-style form of Luther’s machine room solved on a reinforced concrete frame structure. Vasilyev and Bubyr established a temple of plywood furniture with the elegant concrete structure provided with large windows both in the aisle and nave. The production itself required a modern layout suitable for representing the modern material of plywood both symbolically and commercially. It must be noted that better manufacturing facilities and technological innovations were based on a monolithic reinforced concrete frame, but the façade solution with its Art Nouveau shape clearly refers to the Luther family tradition: rough limestone surfaces alternating with smooth plastered exterior.

At the time, the new manufacturing facilities of Luther factory were located in the outskirts of Tallinn, while today it is an active city district marked by numerous office buildings studded with residential houses, schools, cafeterias etc. The fields of activity of the contemporary Veerenni district were mainly responsible for defining the possible directions of the new functions much like the structure of the machine room’s spacious interior further restricted by the special conditions of the national heritage. The historic object of architectural heritage becomes a conserved “museum piece” that needs to incorporate the new function in a way as to highlight the historic layers as much as possible. The originally bright and spacious machine room demonstrating the beauty of construction has today turned into a three-level office building. It is ironic that the 21st century office worker’s expectations for a good work environment coincide with the dream of the previous century’s blue-collar workers – air and daylight.

In 1999, the given complex was declared an architectural monument which is accompanied by a number of special conditions setting relatively strict rules for architects and engineers. In case of the given project, most of the restrictions were related to retaining and exhibiting the original reinforced concrete framework. To illustrate, for the first time, the machine room visitors can see the pyramidal loadbearing columns on the lower level. Earlier, the given structural element was hardly an object of particular interest unless to architecture connoisseurs. Considering the poor condition of the building after left abandoned, the restoration and accommodation of new functions was a challenge for both builders and architects.

The task of creating an improved environment in the historic factory building was undertaken by architects Hanno Grossschmidt and Tomomi Hayashi (HGA) in cooperation with interior architect Kadri Tamme. The handwriting of the machine room differs considerably from the architects’ previous take at an industrial heritage project with the Flour Storage buildings in Rotermanni Quarter dating back to the pre-crisis period, with only some similarities in the materials. In the past few years, such projects have come to change in form – it seems that if previously it was attempted to incorporate the industrial heritage in the urban space by means of modern extensions (e.g. Fahle building, Old and New Flour Storage Buildings in Rotermanni Quarter), then today the emphasis is on researching and highlighting the possibilities of the existing space. So, the architect’s presence has become less evident from the common user’s perspective.

The success of the machine room restoration and regeneration project is largely dependent on the architects’ good work but also on the historic background of the building. The Luther family began developing Veerenni district for their own usage in late 19th century. With the business thriving, also the building complex in Luther Quarter came to increase. Although the process was methodical and rational, it resulted in a comprehensive architectural environment blending well into the urban scene.

In addition to blending harmoniously into the city, the office also requires a rational and comfortable work environment for employees as well as visitors. The interior design largely relies on concrete, glass, limestone and plywood that was used already in the Russian architects’ days. The interior walls had been previously plastered, however, the exposed stone walls today seem to aim at recreating a “more authentic” impression. All modern wires are kept hidden to highlight the historic space. Old structures and walls are noticeably separated from the new ceilings supported by black metal columns. The past and the present of the machine room are thus together under the same roof but at the same time also clearly separated.

DARJA ANDREJEVA studied art history at the Estonian Academy of Arts specialising in the 29th century architecture.

HEADER photo by Tõnu Tunnel.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 spring edition (No 93).