When it comes to housing policy, we talk about something very dear to all of us—our homes. Now is a good time to review what we have already accomplished, and to detect the main shortcomings and obstacles but also the missed opportunities in developing the housing sector. The topic is discussed by the Head of Housing Policy of the Ministry of Climate Veronika Valk-Siska.

Dwelling in numbers

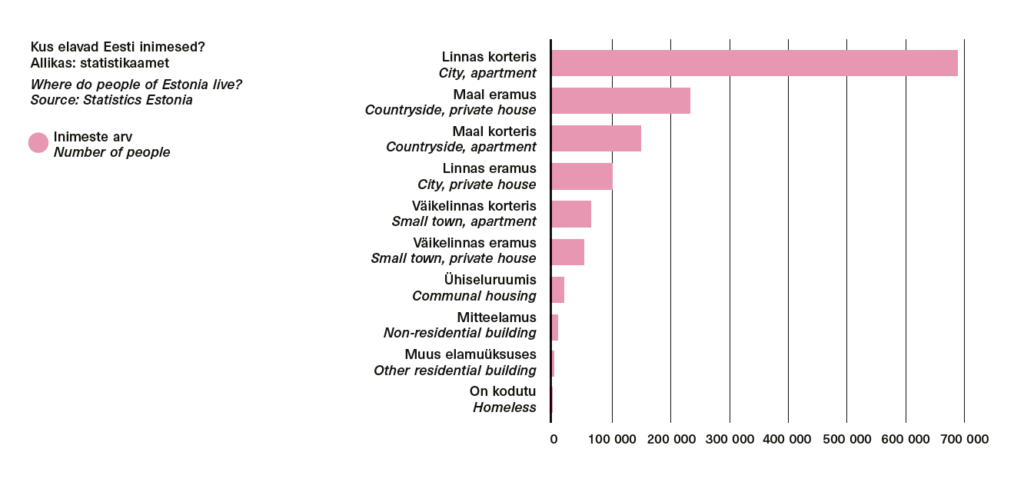

According to the latest housing and population census, there are 266,475 residential buildings in Estonia. Altogether 77.5% of them are single-family homes, 18% apartment buildings, 3.2% semi-detached houses and 1.3% non-residential buildings that include at least one dwelling. Or to put it differently, 27.7% of the inhabited standard dwellings are detached houses and 69.8% apartment buildings (with three or more flats). We also know that the dwelling of an average Estonian resident is older than her.

In Estonia, the surface area of a dwelling has increased but still remains below the Scandinavian average. At the same time, households around the world are getting smaller.1 Among the Baltic countries, the number of standard housing in the past decade has increased the most in Estonia (13%, in Latvia and Lithuania ca 5%).2 Also the increase in detached houses in the past decade has been faster in Estonia than in Latvia and Lithuania. Compared to Estonia and Latvia, residents of Lithuania are more likely to live in dwellings owned by themselves or their family. In Lithuania, 91% of dwellings are inhabited by their owners with only 3% of rentals and 6% marked by other forms of ownership. In Estonia, 70% of residential premises are used by their owners and 19% by tenants with 11% of dwellings used for other purposes. In Latvia, 64% of housing is used by the owner, 17% by tenants and 19% for other purposes. Since regaining independence, Estonia has been highly active in privatisation (similarly to Romania and Slovakia).3

Earlier strategic goals

The Estonian Housing Development Plan 2008–3013 is the last strategy document of the housing sector setting out the goal of ensuring for Estonian residents the availability of suitable and affordable housing,4 high-quality and sustainable housing stock, diversity of residential areas as well as balanced and sustainable development.5 It was a logical continuation of the Estonian Housing Development Plan 2003–2008. The content of both development plans has been focussed on economic issues, including energy efficiency (reducing the monthly housing costs), and less on the social and cultural dimension of the housing sector. According to the goals formulated so far, it is the state’s task to provide such conditions on the housing market (legal and institutional regulation and support measures) that would allow residents to independently solve their housing problems and the associations operating in the housing sector to develop the field.

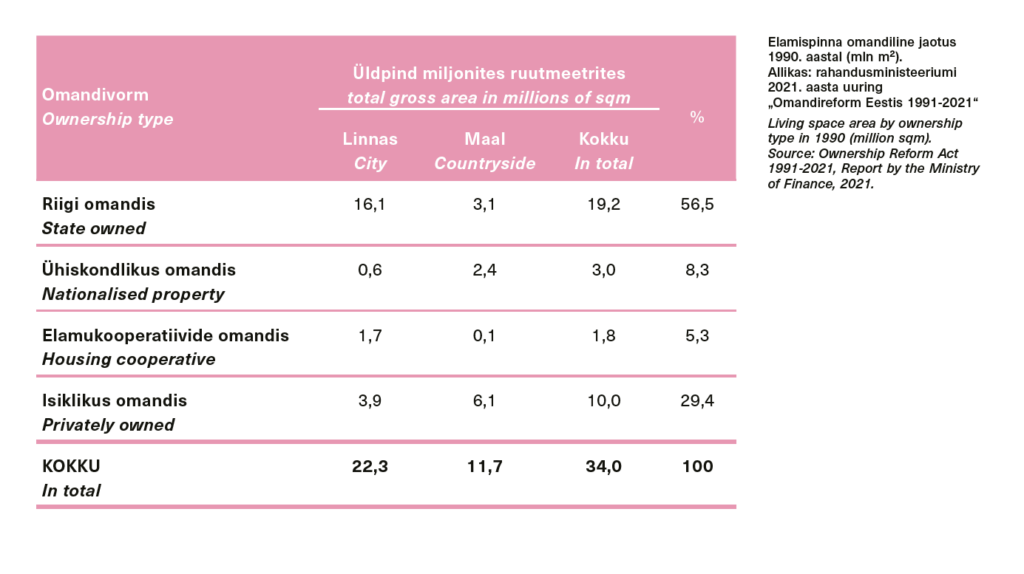

By the beginning of the transitional period, a third of the Estonian housing stock was seriously outdated. The housing stock owned by the state and municipalities was in a particularly bad condition that according to the State Housing Board annually required at least 480 million kroons to be maintained and twice as much for complete renovation.6 After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly independent country had to rectify it all which proved to be a highly complex, even an overwhelming task. We may thus consider the mass privatisation of housing as a transfer of economic responsibility to the residents. By 2001, 90% of dwellings had been privatised. In 2007, altogether 96% of the housing stock was owned by the private sector and 4% by the public sector (with 25% owned by the state and 75% by local governments). By now, the share of private property in the housing stock has increased further. Most of the private rental premises in Estonia are still owned by smallholders, so the sector is poorly controlled from the taxation point of view and the state has no clear regionally precise overview of it.

The concerns of the field have largely remained the same over the decades: the availability of high-quality housing in terms of both economic and physical accessibility, reducing housing costs, problems of urban planning (incl. the connections of public space and the social and cultural infrastructure, linking public transport and non-motorised traffic with the housing development), massive urban sprawl, that is, the so-called fat deposits around major cities, the deterioration of protected neighbourhoods (with a few exceptions in larger cities), the shrinking patterns,7 low involvement of residents, local governments’ lack of capacity to consider the housing development and to implement the visions when developers set their rules from a position of power etc. In the area of housing, the market economy development framework has led to an ever-increasing segregation and the marginalisation of regions. For more problematic regions, it may lead to even higher future costs than the immediate and timely investments in the housing development that should be well-considered and managed by the local government.

This is not a new concern, such descriptions may be found in various analyses and studies. The Estonian Housing Development Plan 2008–2013 formulated an appropriate vision and mission for tackling the given problems, however, now, ten years after the end of the previous development plan period, we are not significantly closer to reaching the goals. This is largely because the ability of local governments to have a say in the housing development matters has not improved sufficiently. The small revenue base and human resources of local governments hinder them in dealing with it more efficiently. Furthermore: the review ‘Housing Policy in Transitional Countries’ by Praxis highlighted already in 2004 that housing policy has been more successful in countries where the rent-oriented policy was implemented together with the decentralisation and deregulation of the rental sector (Poland). In Romania, Bulgaria, Estonia and partly also in Slovakia, the conditions of the privatisation of residential premises with the right of pre-emption (price and extent) were defined by the central government, leaving local governments virtually without any opportunity to protect the interests of local residents upon privatisation. In these countries, the proportion of municipal housing stock has decreased sharply.

The needs of the new generation

With the rise of civic initiative and urban activism, there has been a marked increase in demand for higher-quality housing across Estonia, the kind that fully complies with quality principles.8 Residential spaces should be considered integrally on all spatial levels and in the context of the respective socio-physical relations.9 A good living environment must not only perform well in terms of economy, ecology and functionality but also meet people’s social, cultural and psychological needs. This does not stem only from the Estonian national development goals and strategic documents but also those of the European Union. Adherence to the principles of the New European Bauhaus10 (sustainable, beautiful, together) is a prerequisite for the use of external tools concerning the development of the living environment, including the infrastructure.

This is also where the key role of architects in designing high-quality housing comes to play. In case of both renovation and new-builds, it is the architect who bridges the aims and wishes of very different stakeholders—experts and institutions, clients and residents. Architects tend to play a central role in all stages of spatial design, often in leading the process, mediating and interconnecting the various skills and expertise (engineering, technology, social sciences etc.) and conceptualising the resulting synergy. But also all other parties, both public and private, bear the obligation to ensure compliance with quality objectives to the best of current knowledge in decision-making, planning, design, construction and reconstruction as well as in other forms of reuse.

Local governments as the creators of the spatial vision of clever shrinking and rental housing

According to the Constitution and the Local Government Organisation Act, local governments are responsible for the organisation of housing and communal services in their administrative territory. The question of the need for empowering local governments arises particularly in the case of shrinking towns and villages. The average number of vacant residential units has multiplied in the past 20 years. In the long-term strategy for the reconstruction of buildings (2020), it is estimated that up to 25% of detached houses (around 40,000 buildings) and up to 23% of apartment buildings (around 5300 buildings) may remain vacant in shrinking towns and villages by 2050. Almost all Europe is aging and shrinking with dignity—shrinking is not necessarily bad and growth good.

The challenge of a shrinking population is not new for Estonia—the Estonian settlement system is centuries old and there have been various changes in the population (including vacant settlements) considerably earlier than in the past 10–20 years. The new question is how to implement the Green Transition in areas with no support from the market, that is, how to use scarce funds wisely and how to ensure high-quality living conditions across Estonia. For the remote workers, the world is open to find a place with a better living environment (or the opportunity to improve its quality).

The city of Valga serves as a good example of the spatial re-conceptualisation of a shrinking town. When thinking about what we can do in areas with shrinking population, the first rule is to accept the situation. In the case of Valga, it meant that its policy-making should not be based on 18,000 people when 6000 of them have left, instead they should focus on the 12,000 remaining residents and making Valga the best place for them. We cannot just talk about investing only in the energy efficiency of buildings to reach the goals of the green transition, instead, we have to focus on providing good living conditions for the residents of these houses and towns even if it means that their building uses more energy.

Simultaneously with the shrinking, there are also strong magnets among smaller towns that offer new attractive jobs but lack modern high-quality dwellings. The construction or reconstruction of modern rental housing meeting contemporary needs is therefore vital in combating marginalisation, as it will result in a strong infrastructure and help to keep and attract new people—skilled labour—who consider the quality of housing as a decisive factor.

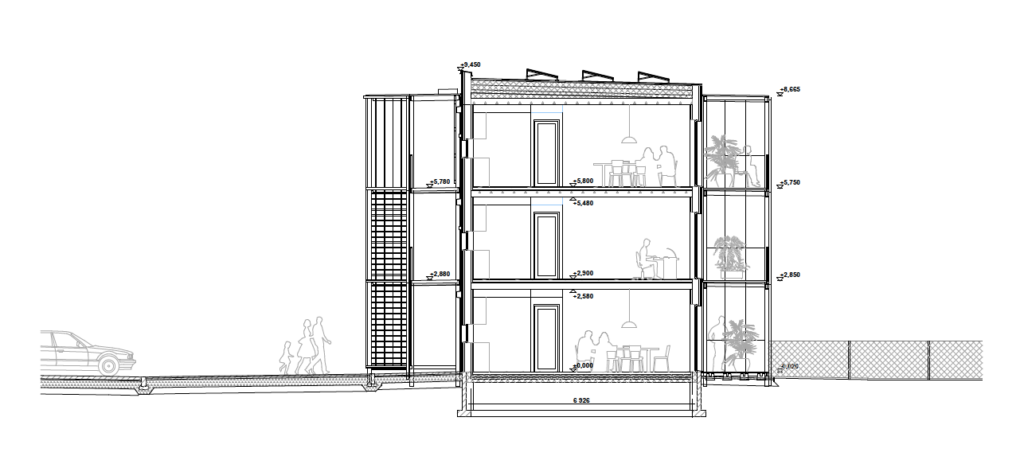

Since 2017, local governments have been able to apply for state support for the renovation or construction of residential properties for up to 50% of the total cost of the project.11 The aim of the grant is to improve the availability of high-quality and affordable housing. The target group of such housing primarily includes those employees (with their families) who lack affordable housing meeting contemporary needs as well as socio-economically disadvantaged residents who cannot afford market rents. So far, 13 new buildings have been constructed and 8 reconstructed with the support.12 It may be applied for both, new-builds and reconstruction of a rental building. In the most recent call in 2023, more attention was paid to the assessment of the spatial impact of the proposed projects and the adherence to the principles of a high-quality solution.

So far, rental houses completed with state and local government support have been successful and the experience shows that much more resources should be allotted to the rental housing programme. However, neither the new coalition agreement nor the government work programme includes the issue of rental houses, thus making it difficult to use state budget funds for the given purpose. On the state level, the rental housing programmes are discussed in the light of stimulating housing stock development by other means (financial measures for private investors, private-public-partnership i.e. PPP models etc.). In a way, also the current applications are based on the PPP model as the grant conditions allow including the private sector as an investor in case the local government lacks sufficient self-financing. An important point here is that the funder-partner is found through a competitive situation, that is, as a result of a public competition. It is important to consider the possible setbacks in case the local government is not strong enough to control individual interests and steer the development of the housing sector on the basis of the agreed spatial vision for the common good. In other words, it would be wrong to provide the private sector with levers without a spatial vision initiated by the public sector of where and why the investments will be made. Once the vision is agreed to improve the quality of life for as many people as possible for as long as possible, it can be implemented in cooperation with different sectors.

Local governments—leaders of the renovation boom

Preventing urban sprawl, steering the development of residential areas, ensuring diverse living environments, maintaining the vitality of protected areas, developing the public space and infrastructure of local centres etc.—all these are within the exclusive local government competence. Similarly, municipalities play a crucial role in the surge in renovation, as neighbourhood-based renovation requires a vision and spatial solutions also for the (semi)private and public spaces between the buildings. The creation of such comprehensive neighbourhood-based solutions should be led by the local government in cooperation with the residents.

The aim of the long-term strategy for the reconstruction of buildings is to improve in the next 30 years the conditions of the homes and workplaces of up to 80% of the Estonian residents. It requires large investments and it is expected that a considerable part of the reconstruction work is conducted on the initiative and funding of the owners. This brings us to another important reason why more capable municipalities are needed than ever before: often the question is how to engage communities in a meaningful way to discuss the development of their living environment and eventually implement the common visions together. Residents—communities—undoubtedly have a great interest in shaping their living environment. The cultural impact and heritage should play a far more important role in the spatial decisions made by the local governments. The understanding that heritage is determined by the community requires continuous dialogue between the parties: preserving and developing can go hand in hand. A change in attitude is needed: the task of the public sector is to initiate, maintain and develop the environment and culture of discussing spatial issues.13 Spatial education plays a crucial role here too, it should be provided from an early age.

All hopes on the future Spatial Development Office

As a new competence centre, the Land and Spatial Development Board to be established (presumably in 2025) under the Ministry of Regional Affairs and Agriculture is expected to provide municipalities with support in the spatial design tasks that they otherwise cannot solve by themselves.

Through the development of the living environment, that is, spatial decisions, the new authority will deal with the implementation of the economic policy while also serving as a link between the construction sector and public agencies. The construction and real estate sectors together constitute almost 16% of the GDP, more than the IT sector and manufacturing industry combined. Around three quarters of construction investments are made by private companies. About a quarter of Estonian entrepreneurs are directly connected with the construction and real estate sector. The green transition requires a surge of investment from both private and public sector which, in turn, calls for improved coordination of investments and increased interaction.14

The Land and Spatial Development Office is also expected to maintain high-quality spatial data, which is the base of 80% of all data-driven decisions made on the local government level. The sustainable development of the living environment (climate plan implementation) is possible only with the help of wise data-driven decisions. The green transition requires a balance between the economic and environmental goals. The implementation of the green transition depends on how spatial data are seen and analysed on the regional and local level between the areas of nature conservation, energy, transportation, construction and housing.

Boosting the synergy of the measures

Regarding investments, we should see the wood for the trees: all of the investments must improve the life of as many people as possible for as long as possible. Therefore, it is important to make sure that all investments, measures and tools, both external (EU Cohesion Policy funds, European agricultural fund for rural development, ‘European Horizon’ programme and its relevant missions, Creative Europe, Erasmus+ etc.) and national, regional and local funding decisions and services consider the comprehensive quality goals of the living environment at large. The aim is to design a comprehensive living environment which is often hindered by plot- or building-based decisions instead of the implementation of a neighbourhood-based approach. Another risk, for example, is the purely cost-based procurement logic while large investments should primarily rely on a value-based approach. The culture of spatial governance at large is in need of attention.

What kind of measures in addition to reconstruction subsidies are we talking about? Mainly the regional grants of the new funding period of EU structural funds (2021–2027). Increasing the synergy of the measures means a more substantial and increased cooperation between agencies so that the investments in the living environment would serve the common goal and not work against each other and that the housing support measures would follow the unified national policy as well as the relevant conditions and methodology stipulated by the Ministry of Climate and KredEx. The conditions for granting support must be based on a uniform assessment methodology that would consider the spatial impact of the projects on several levels, among other things it must be clear how the basic principles of a high-quality space are considered in the selection of the projects. Projects where an architecture competition has been (or will be) held could be rated higher. The involvement of qualified architects and landscape architects and urban sociologists in the investment plans and projects must be a standard and their participation must not be a mere formality but is essential from the early planning stages. In the implementation of the town square programme ‘Great Public Spaces’, for example, it is possible to find even better synergy with other local initiatives that support the well-considered development of the housing sector.

In the implementation of the ideas, local governments would benefit from cooperation, for instance, with universities, various institutions, experts and other local governments. Let’s consider, for instance, the LIFE IP BuildEST or renovation marathon project15 aimed at updating and implementing the long-term strategy for the reconstruction of buildings in Estonia primarily in terms of energy efficiency. A good example here is the BuildEST initiative in the town of Võru: owners of the town centre buildings get renovation advice from experts with an emphasis on compliance with energy efficiency and heritage protection requirements.

In order to ensure that the implementation of EU funds does not focus mainly on energy efficiency, we also need projects that consider the social and cultural dimension of the living environment. Therefore, it is highly significant that the Ministry of Climate in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture, National Heritage Board, Estonian Academy of Arts, ICOMOS Estonia and TalTech will soon launch a new project LIFE HeritageHome focusing on the renovation of buildings of cultural value. The project is meant for the owners of about 7000 buildings under heritage protection or located in a heritage conservation area. Or, let’s take another example: the winners of the European Urban Initiative project grants were announced in June this year. Among other successful projects, five million euros were allocated to SOFTacademy led by Tallinn which aims at accelerating the renovation of large multi-owner apartment buildings in the district of Mustamäe in a new way that would encourage the transformation of the entire neighbourhood, including the public and semi-private space between the buildings. To this end, an innovation model will be devised to accelerate the inclusion of the private sector (incl. residents and owners) in the renovation led by the city government. In the process, the housing quality will be improved, biodiversity between the buildings increased, community facilities adapted and a cosier and more livable environment created. The intervention logic and digital tools will probably be transferable to other similar pre-fab residential districts in order to trigger a change that could provide residents with a stronger sense of place and identity.

In conclusion, time has come to take a new direction at state level and initiate changes that would increase the availability of high-quality housing (in cooperation with the public and private sector, e.g., by means of rental building programmes, financial instruments etc.), strengthen the role of local governments in developing the housing sector, enhance the synergy between various support measures and, in line with the New European Bauhaus, focus much more on the quality objectives of the living environment as a whole, including the social and cultural dimension of the housing sector. It also means the establishment of the Land and Spatial Development Board as a spatial design competence centre. Among its tasks: to help municipalities to multiply the volume and pace of renovation. The time is also right for neighbourhood-based renovation pilots and pre-fab renovation, using all available resources for the comprehensive development of the living environment, that is, both local, national and EU grants as well as financial instruments (loans-guarantees). This means developing the living environment not by individual buildings but in a holistic way, together with public spaces and the areas between the buildings. It has to be done from the resident’s point of view, as this will determine their sense of place, in other words, the community’s overall cognitive connection with their neighbourhood. Everybody wants to be proud of their home and its surroundings so they have faith in its future.

VERONIKA VALK-SISKA is an architect and the Head of Housing Policy at the Ministry of Climate. Previously, she was an Advisor on Architecture and Design at the Ministry of Culture.

HEADER: In Valga, a more than 100 years old art nouveau building was renovated as part of the state’s rental housing programme. The building is locally known as the house of three lions. It is now rental housing for qualified workers. Photo by Helena Spridzane

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing

1 The size of dwellings in square metres per resident has increased: it was 31.4 m² in 2000; 42.6 m² in 2011 and 43.9 m² in 2021. The size of dwellings in apartment buildings with three or more flats has decreased compared to 2011: from 24.8 m² to 23.8 m². In other words, detached houses are on average larger and flats smaller than during the previous census. See more on the census website of Statistics Estonia.

2 Eesti eluruumid on väiksemad kui Lätis, aga suuremad kui Leedus’, news on the census website of Statistics Estonia, 19.08.2022.

3 Anneli Kährik, Martin Lux, Jüri Kõre, Margus Hendrikson, Ille Allsaar, Eluasemepoliitika üleminekuriikides (Tallinn: Praxis, 2004).

4 Housing is a dwelling or a part of a dwelling suitable for the year-round accommodation of one or more households. In exceptional cases, it may also consist of several dwellings, for instance, when the members of the same household use several adjacent dwellings. In socio-cultural terms, housing is equated with the concept of home.

5 Eesti eluasemevaldkonna arengukava 2008–2013. Prepared by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communication (sent for approval on 16.01.2008).

6 Omandireform Eestis 1999–2021. Compiled by the Ministry of Finance (Tallinn, 2021).

7 See the nationwide survey of building vacancy and the patterns of shrinking by Cerrone et al in 2022.

8 See the resident satisfaction survey in 2022 on the website minuomavalitsus.ee.

9 ee the study report ‘Valued spaces of residing in Tallinn: conceptualising quality of life in the interacting private and public spaces. The processes of gentrification, renewal, diversification and (re)connection in the perspective of users’ by Paadam et al in 2014.

10 See the Communication COM (2021) 573 of the European Commission of 15 September 2021.

11 Anete Altrov, Ivo Jaanisoo, Riiklikult toetatud üürielamute programm, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communication (August 2022).

12 Three new additional projects are expected to get funding from this year’s call.

13 See also the final report of the research project ‘Tallinna vanalinna jätkusuutlik areng ja eksponeerimine’ by Triin Talgi, Raul Kalvo, Liis Ojamäe and Katrin Paadam titled ‘Vanalinn. Pärand, elukeskkond, turism’ (Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, 2023).

14 Listen also to the section ‘Väga suure osa rohepöördest saab ära teha ehitussektoris’ of the podcast ‘Rohepöörde praktikud’ by Äripäev (31.05.2023).

15 See about LIFE IP BuildEST on the website of the Ministry of Climate.