After the slow-burning and partly contestable success stories of Rotermann Quarter and Telliskivi Creative City, the eyes of Tallinners interested in urban design or just longing for a better urban space turned to Noblessner—the privately developed waterfront set to become one of the first chapters on the road to open the coastal areas of Tallinn to its citizens. Though far from complete, the lively quarter already offers a chance for a status report and an insight into the entrenchment of certain spatio-social tendencies in the Estonian real estate landscape.

Already ahead of its completion, Noblessner Quarter has been labelled as another success story of architectural recycling and real estate development (1) that has been well received by the business sector, professionals of the architectural field (2) and urban development, the citizens of Tallinn, the clique of the art world and the heritage protection (3) —a rather extraordinary feat in itself. The area is home to several renowned arts and cultural organisations, restaurants, a craft beer brewery with the never-ending buzz generated by a constant flux of outdoor events and lively street life that reaches its apex during the sunny summer days and evenings. It is one of the few areas in Tallinn that meets the urban standards devised by the proponents of the New Urbanism movement and also plays a leading role in the gradual fading of urban life in central Tallinn.

The first good example in Tallinn?

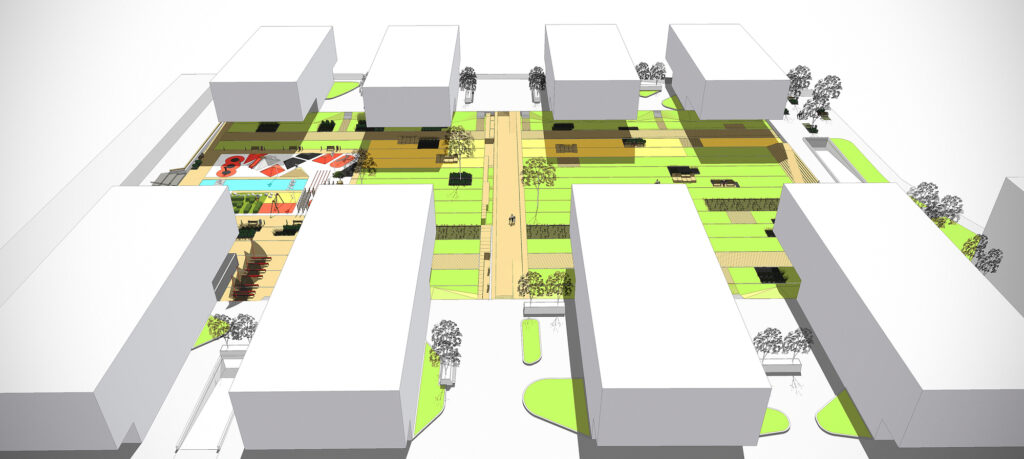

The success of Noblessner is the result of some provident architectural and planning decisions and effective collaboration between various disciplines involved in the process. The attraction of the sea and the proportion of public pedestrian space also have a role to play. The European cities topping the lists of urban quality have usually based their success on the following features: strictly limited building heights, multifunctional urban spaces, opening the street front for small businesses and designing pedestrian-centred traffic solutions. The latter means limiting car speeds, accesses and parking in key locations—something Tallinn has been really struggling with so far.

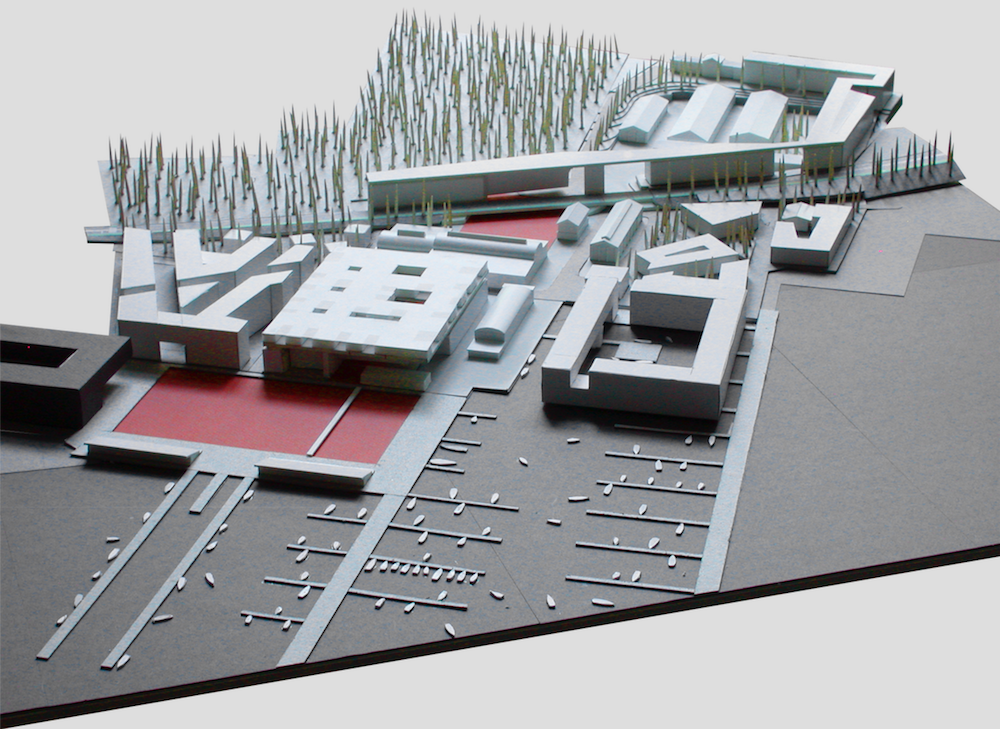

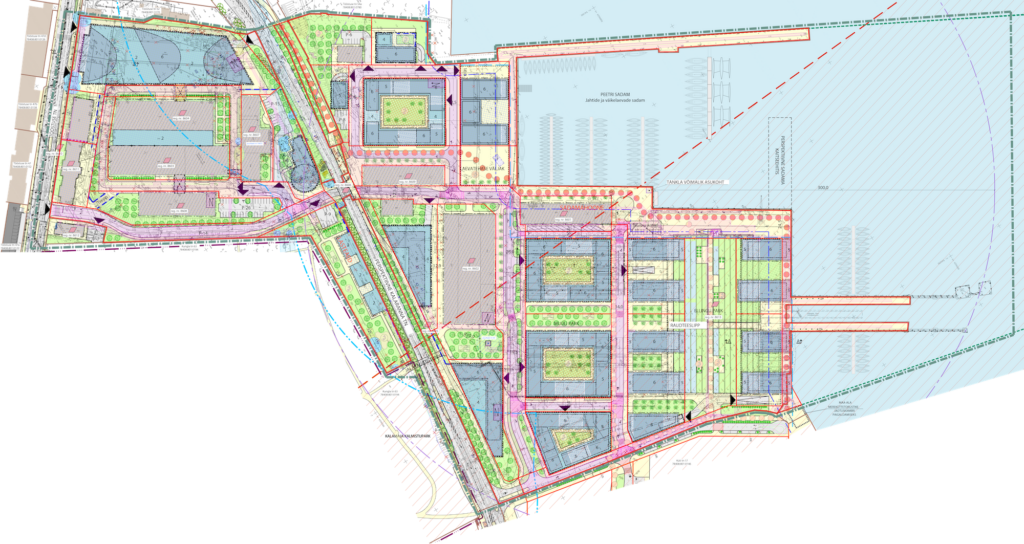

When looking at the original competition design by the winning Danish studio Hvidt & Mølgaard from 2007 and the detail plan based on it (K-Projekt, 2013), it comes as a positive surprise that over time the plans have become less car-centred, for example, the central square of the quarter is currently completely car-free, not like in the 2013 detail plan which envisioned a smaller square edged by a two-lane road. The final solution benefits greatly from the reduced physical presence and lack of visual noise generated by cars, creating a dynamic urban square with enough space for large-scale events—something that has become a regularity there. Not everything is completely rosy though, as the dominating landscape feature of the quarter is actually Kalaranna Road cutting straight through the area and set to see a drastic rise in traffic as the development in the western parts of Tallinn intensifies.

Assessing the landscape design south of Kalaranna Road made by Estonian landscape architects Kino (2015-2017) proves difficult as several bits of it—including a small park near

the pier and a children’s playground—have not been built according to their designs. Kino’s boat-shaped seating/flowerbeds and the expressive red street lighting posts designed by Rebecca Pütsep (Pluss Architects) reminding of dock derricks bring some playfulness to the otherwise bleakish environment dominated by limestone walls and grey tiles, something the minimalist design does not benefit from most of the year in the Estonian climate. This feel is slightly reduced on the main square by its active use by different hybrid forms of commercial enterprise and marketing, including the igloo saunas. In terms of greenery, it is difficult to escape the feeling that a portion of ‘lushness’ has been lost in the translation of initial renderings into the actual physical space. It seems to follow a general tendency in Tallinn to avoid the use of vegetation in coastal designs (e.g., Tallinn Cruise Ship terminal, the bike lanes of Reidi Road, Pirita Road) to mitigate the strong effect of maritime winds, thus strongly favouring views over wind control.

Architecturally the visual unity is achieved mainly by well-specified volumes (especially vertical ones) but also the quality of the restoration work that followed a similar logic to remove the Soviet constructions and restore everything older. It is also important to note that the high-rise residential building right by the pier in the original design was blocked by the National Heritage Board. The completed new architecture, in general, has fewer stellar individual buildings than, say the Rotermann Quarter had during its first stages, however, the district is much better connected to the rest of the city and has more coherent public spaces. The eclectic facades of Staapli 3 and 4 as well as Allveelaeva 4 currently under construction—all designed by Pluss Architects—seem to simulate the well-known visual imagery of the high-density historic facades of Amsterdam canal sides, while also trying to minimise the rather extensive volumes—the facade of Staapli 3 is nearly 70 meters—and thus cutting costs for the developer. Most ground floor spaces are reserved for commercial premises to enliven the street life: the quarter is currently home to 21 service providers and 13 restaurants and bars.

The homogenous five-building ensemble on Vesilennuki and Lennusadama Streets by KOKO architects, currently under construction, are noteworthy mainly due to the protruding balconies that set the stage for a social spectacle, while seeming to require highly evolved exhibitionist traits among its residents. Due to the strong and frequent winds in Tallinn, their use will be quite limited. It is a pity that Kino’s designs for Slipway Park (derived of the former ship launch platform under heritage protection) adjacent to the ensemble will not be realised in their current form, but according to Ann Virkus (the representative of the developer BLRT) this will remain a green space. Truth be told, the launch platforms are visually not the most interesting heritage objects and the area could use vegetation to avoid the formation of wind accumulation that is very likely to occur between the buildings.

On gentrification and social diversity

As pointed out in the Estonian Human Development Report (4), both the legal definition and actual spatial organisation of public spaces is problematic in Estonia. Some of this can be felt also in the context of Noblessner: after the euphoric opening of the new public pier with several bars and restaurants, the space soon became a victim of its own success with an announcement that the area was only reserved for the clients of the catering facilities during their opening hours. While the entrepreneurs’ interest to maintain public order on livelier weekends is somewhat understandable, this step immediately rendered the recently regained seaside area more exclusive. This is further amplified by the igloo sauna park next to the piers that similarly commercializes a notable swath of land. This way a considerable proportion of the neighbourhood is turned from a public to semi-private (and commercialized) space where a particular part of the society will no longer feel welcome. One can only hope that in future, when the dust of all the costal developments of Tallinn has settled, the only non-commercial public space at the seafront will not be the narrow linear park next to the recently completed six-lane Reidi Road…

The commercialization of public space in Noblessner is symptomatic of a wider tendency in Estonian spatial policies: there seems to be a default social agreement that the land by water bodies is a value to be taxed, both directly and indirectly, thus making it socially exclusive. The tax rates of municipalities for coastal areas are generally higher and there has been no real attempt to create social diversification in attractive neighbourhoods by requiring that developers offer also diversified housing.

This only greases the wheels of social stratification and the increasingly relentless pace of economic gentrification that render an ever-increasing part of the city, under the banner of rejuvenation and improvement of life quality, completely inaccessible for a considerable part of the society—as recently confirmed also by an extensive analysis co-conducted by Levila and Eesti Ekspress. Still overcoming its trauma of communism, the free-market acolyte society of Estonia has been particularly open to these processes and some of the urban planning specialists with a more sensitive social nerve enviously look up to the city of Helsinki that owns 70% of the land and thus also has a lot more in its arsenal (in addition to political will) to combat spatial inequalities manifested in spaces of higher quality.

Planning historian Samuel Stein has described the history of planning mostly as an instrument serving the interests of the financial elite that in the US (excluding some utopian world-improvement visions of the 1950-1960s) has always led, one way or another, to the implementation of an economic segregation programme (6). Taking a socio-critical look at the Estonian context, North Tallinn is a prime example of a neighbourhood that in the course of an urban renewal process has become completely ‘cleaned’ of people of particular socioeconomic background. When thinking of the developments waiting for their turn—Patarei, Hundipea, Kalaranna and Kopli Liinid—there seems to be no end to this process in sight.

Retaining socio-spatial diversity is of key importance to preserve the vitality of the social fabric of the city, to avoid the ghettoization and economic marginalisation of entire districts as well as the alienation of the different segments of the society. In Western and Northern Europe, certain steps have been taken to avoid this. Paris is building tens of thousands of municipal rental apartments (often recycling high-value historical architecture (7)), including in the highly attractive city centre (8) and 18th-19th century buildings (9). In the Netherlands, on the other hand, it is not uncommon that a street with 300-square-metre villas are in the vicinity of a social housing street with the economic differences carefully concealed by good planning and architecture. Perhaps Tallinn should find the courage and consider an upgraded social housing programme that includes more variety than a couple of low-value cubes on the outskirts of the city?

Noblessner bears witness to some elements of another typical scenario that Stein has described: most of the industrial production, even those with low levels of pollution, are forced out of the city (usually as a result of the developer’s lobby) and the areas are transformed to meet their potential market value, which is almost always artificially inflated. So it is not uncommon that some of the more agile industrialists turn developers—something that also happened here, as the ship repair yard BLRT saw a completely new field of operations added to their portfolio (10). It is, of course, hard to object (11) the fact that a large proportion of populace of the nearby areas, already gentrified, benefit from this process as they prefer refurbished residential areas to industry.

This does, however, raise the question of what becomes of the gentrified area in the long run, who benefits from this and how much, and, of course, what the effect will be on wider societal developments. The real estate business is displaying similar accumulation of wealth as other sectors and it always occurs at the expense of the general populace—as land in the cities, even privately owned, is part of a collective space—an idea still quite foreign in Estonia when compared to some other European societies. Then again, it must be said that with some new housing projects, the responsibility for creating improved public space is on the rise and effort is made to create values on a wider scale rather than just for the new residents. In this light, Noblessner, albeit with the above-mentioned concessions, can still be considered a step in the right direction.

***

Unlike some other high-profile developments under way in Tallinn, Noblessner can be considered a positive milestone and a success story. The developers and visionaries have been in a fruitful dialogue with heritage protection experts and urban planners and have provided the city with a new patch of aesthetically pleasing (semi-)public space—Tallinn has received a strip of land that is now more open to the sea and several cultural institutions have found a worthy home. And the most important aspect (for a society completely saturated with neoliberal values): the market will see an influx of new highly sought-after real estate for the part of the society that values and can afford this type of a SoDoSoPa-lifestyle. It is the wider tendencies in the society, of which Noblessner is also a spatial symptom, that gives a cause for concern.

HANNES AAVA is a cultural critic, columnist on urban issues at the culture gazette Müürileht and a student of landscape architecture

Published in Maja’s spring 2022 edition (108)

Header photo: Tõnu Tunnel

1 – Noblessner won the international award

2 – Karin Paulus “Nooblilt sadamas“, Sirp, 25.10.2019

3 – Monika Eensalu-Pihel, “Metamorfoosid Noblessneris”, Muinsuskaitse aastaraamat 2019

4 – Elo Kiivet, Toomas Paaver, “Avalik ruum kui elukeskkonda siduv võrgustik”, Eesti Inimarengu Aruanne 2019/2020.

5 – Riin Aljas, Oliver Kund, Mari Mets. “Tallinna nähtamatud müürid“, Levila, märtsis 2022

6 – Samuel Stein, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (New York: Verso, 2019), 34

7 – Madeleine Schwatz, Bike Lane to the Élysée (New York Review of Books, 2022).

8 – Rachel Holman, “Low income housing comes to luxury Paris neighborhoods“, France24, 11.03.2020

9 – Colin Kinniburgh, “Paris’s new public housing push aims to offset soaring rents” France24, 11.03.2020.

10 – Samuel Stein, “Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State” (New York: Verso, 2019), 38

11 – Referring to the fictional gentrification project in the animated series Southpark that merges a hedonistic lifestyle, active social life and consumer culture