HELSINGIN MUURARIMESTARI

Architecture: Avarrus Architects (Pauli Siponen, Noona Lappalainen, Niilo Ikonen,

Atte Aaltonen, Erno Laakso, Iida Siponmaa)

Location: Helsinki, Finland

Completed: 2024

Type: Apartment building with 29 homes

Developer: Kestävät Kodit

Builder: SSA Rakennus

With its solid brick walls, Helsingin Muurarimestari, an apartment building designed by Avarrus Architects, is generous to tradition, but decidedly modern, writes Leonard Ma.

One of the most enduring quotes from the American architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller is the provocation, ‘How much does your house weigh?’. Fuller’s question was a challenge to architecture to embrace the new possibilities offered by modern materials and industrial production methods. Embodied by the design for his 1927 Dymaxion house—a lightweight shelter formed by aluminium wedges and a single supporting core in the centre that could be mass-produced and transported to the site—Fuller sought ‘maximum gain of advantage from minimal energy input’1 in his architecture. Doing more with less has been an enduring dictum passed on by modernism, one that still has remarkable resonance today. In the face of an impending climate catastrophe, we need to do more while reducing our carbon footprint and environmental impact.

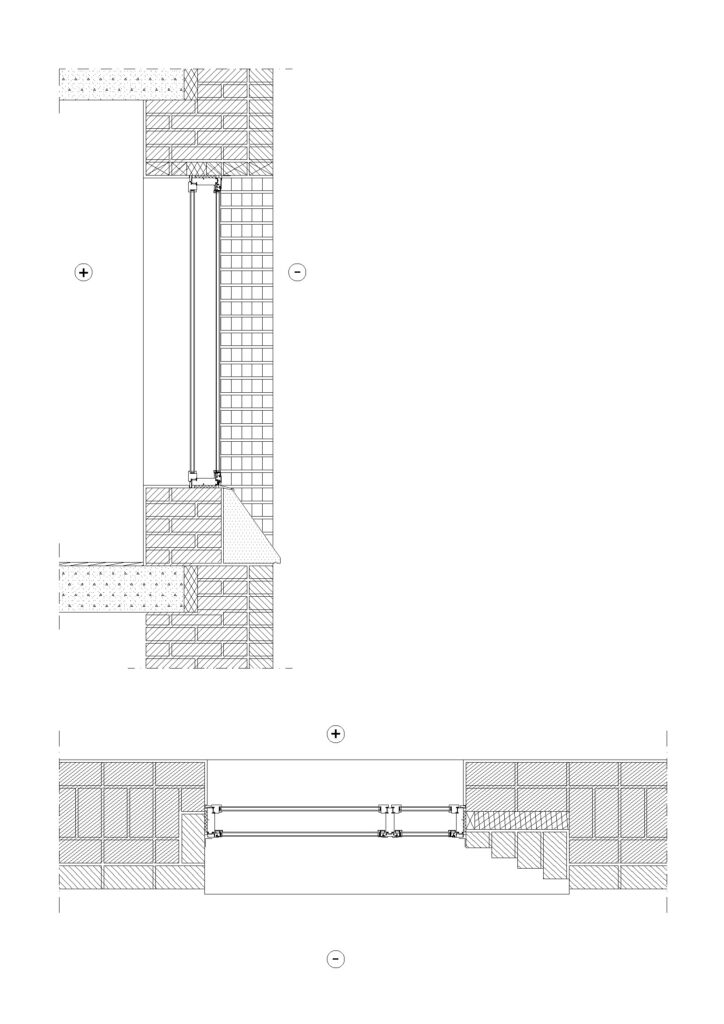

Now almost 100 years later, a new housing project in Helsinki offers an approach that is altogether opposite to Fuller’s geodesic domes and lightweight structures. With its solid brick walls, at times up to 750mm thick, Helsingin Muurarimestari (Finnish for ‘the Helsinki Bricklayer’), designed by Avarrus Architects, is a contemporary and urgent response to the call for sustainable construction. It challenges established conceptions of modern building technologies, where exterior walls are made of multi-layered assemblies of cladding, insulation, and structure. Each layer in such an assembly performs a specific role: cladding repels moisture and physical damage, insulation retains heat, while the structure establishes physical integrity. Helsingin Muurarimestari offers an alternative solution: a monolithic assembly constructed entirely from brick. The brick provides support for the exterior walls while creating enough thermal isolation with its thickness to retain heat. Simplifying the exterior wall assembly means fewer points of failure where the ingress of air and moisture can result in decay, corrosion, and even mould.

Avarrus’ project is the latest example of a more general preoccupation in Finnish architecture with the material assemblies and technologies taken for granted in building construction today. As the post-war building stock in Finland has aged, it has led to issues with rapidly deteriorating building envelopes. These buildings, utilising precast concrete sandwich elements, were developed based on expertise and supply chains in a globalising economy and brought with them assumptions that have proven particularly inadequate to the northern climate. The buildings made of such prefabricated elements are prone to moisture ingress and freeze/thaw damage which cause rot and decay over time. This is particularly pressing as many of them are not just housing, but also schools, hospitals, and kindergartens, creating alarming indoor air quality situations for those most vulnerable. The issues with mould are further compounded by ageing mechanical ventilation systems that further accelerate the spread of decay. In place of these multi-layered wall assemblies, many architects have started looking at monolithic assemblies inspired by the log and brick buildings of pre-modernist Finland. This debate has expanded even beyond specialist architectural circles, with many newspaper articles and prominent citizen campaigns on the hazards of failing building stock from the 60’s and 70’s. In contrast to Fuller’s vision of an industrialised house, a hermetically sealed building of the future, the provocation for our present times might rather be to ask, ‘How does your house breathe?’.

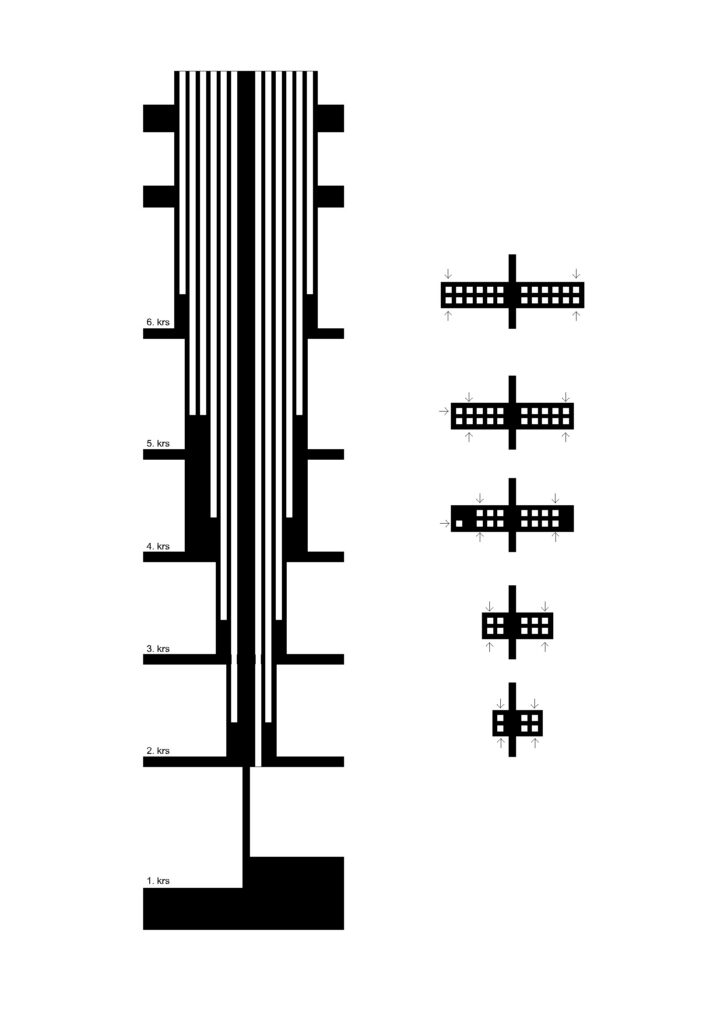

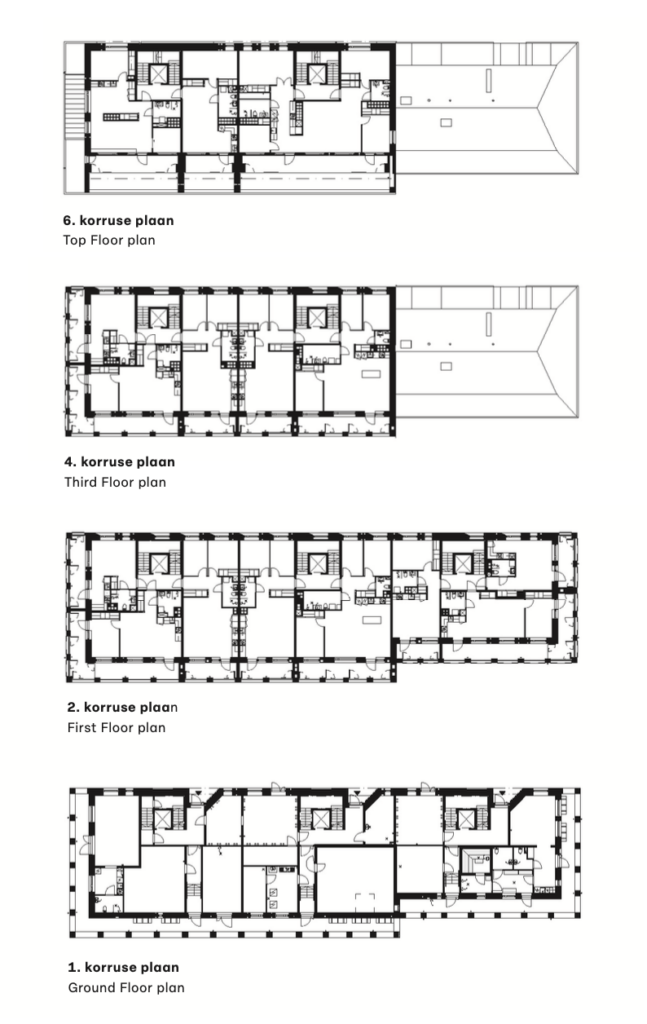

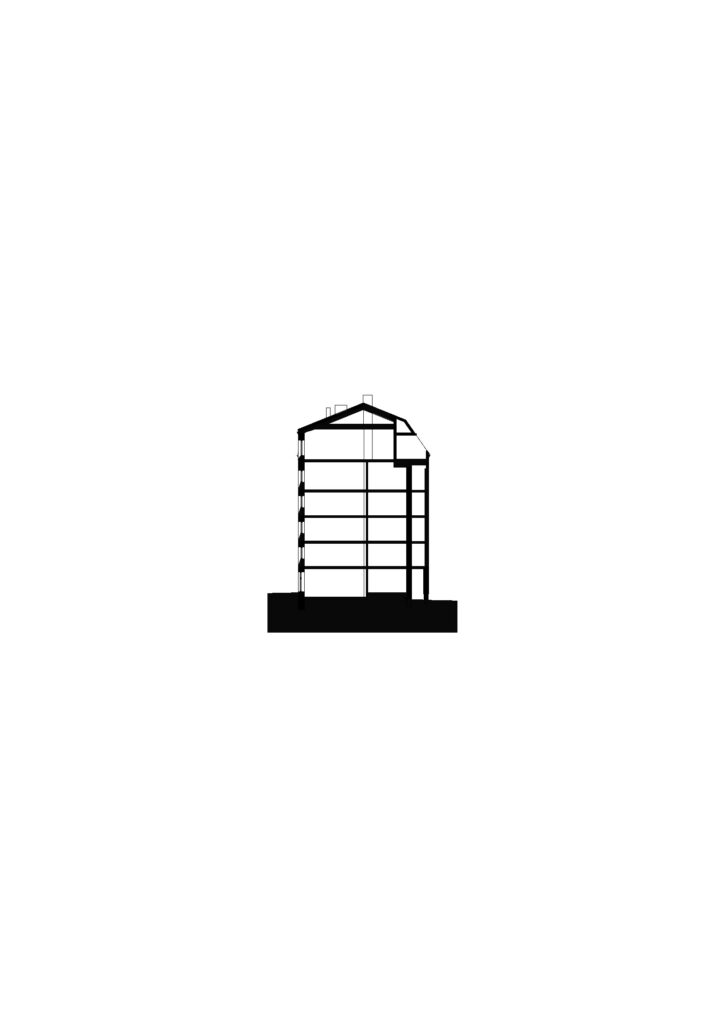

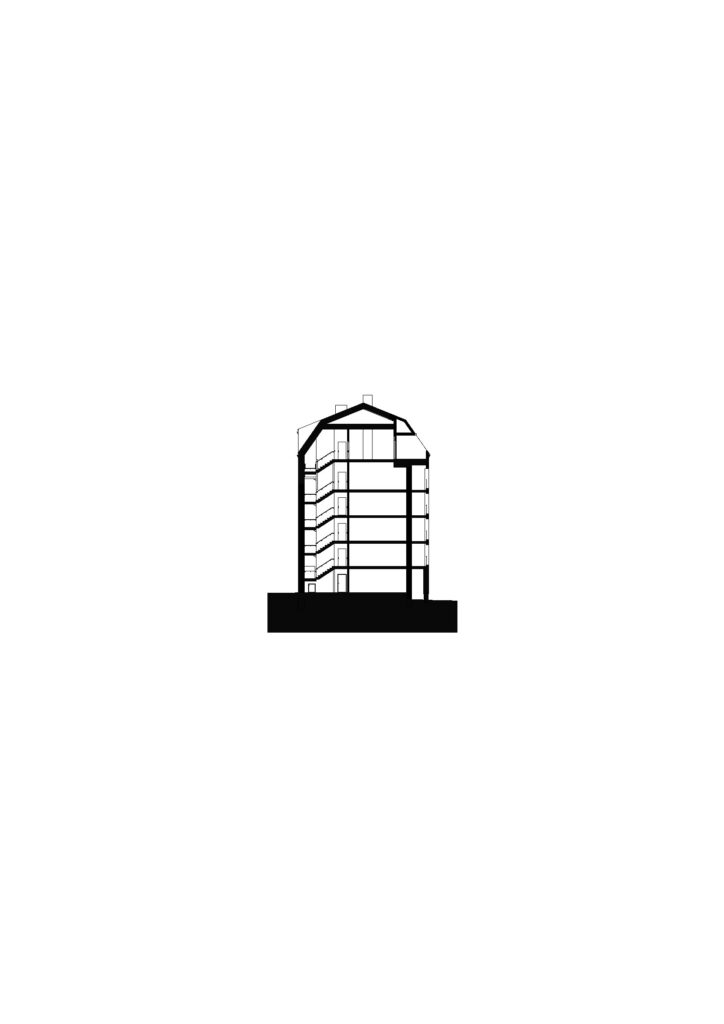

Helsingin Muurarimestari is a rare example of a contemporary housing project that utilises natural ventilation. With increasingly stringent regulations on building performance and concerns about the energy costs in heating and cooling, most new buildings utilise some form of heat recovery and exchange, i.e., a mechanically driven system where the heat from the exhaust air is captured to pre-heat intake air, reducing overall energy costs. Naturally ventilated systems, on the other hand, simply take air from exterior vents and channel them through the building. In the case of Helsingin Muurarimestari, exhaust air is channelled through a brick chimney that leads to the roof. Each unit has its own independent shaft in the chimney, which gets wider on the upper levels as more and more shafts are incorporated into the structure.

The project is a breakthrough in several aspects that might appear mundane at first glance. The thermal performance of the monolithic brick wall assembly required a special exemption from the Helsinki Building Control services, which normally requires an overall heat transfer coefficient, also known as U-value, of U=0.17 W/(m2K). However, Helsingin Muurarimestari was approved under the less stringent U-value of U=0.4 W/(m2K) for wooden log construction, a valuable precedent for future monolithic brick buildings. Despite the lack of modern heat recovery and exchange systems, the first few years of monitoring have shown that the performance is comparable to that of a more standard building. Heat exchange systems and mechanical ventilation have their own built-in energy costs, inevitably requiring electricity for their operation. The thermal mass of the brick structure has also performed surprisingly well in regulating temperature—something that is challenging to model with current building simulation models.

There is also an inevitable tinge of conservative nostalgia that permeates the discussion around the project—that things were just better in the ‘good old days’. The architects say that they’ve shown the building over 350 times since it was completed two years ago—not just to architects and other building professionals, but also to those interested in traditional forms of construction and ventilation. The monolithic brick walls and chimneys harken back to the Nordic Classical buildings of the turn-of-the-20th-century Finland. Many of the oldest (and most expensive) neighbourhoods in Helsinki were built in this way, and it carries with it a timeless and enduring quality that is deeply rooted in the Finnish psyche. Indeed, one of the main disappointments for those looking for a more traditional building is the absence of oak windows and fireplaces.

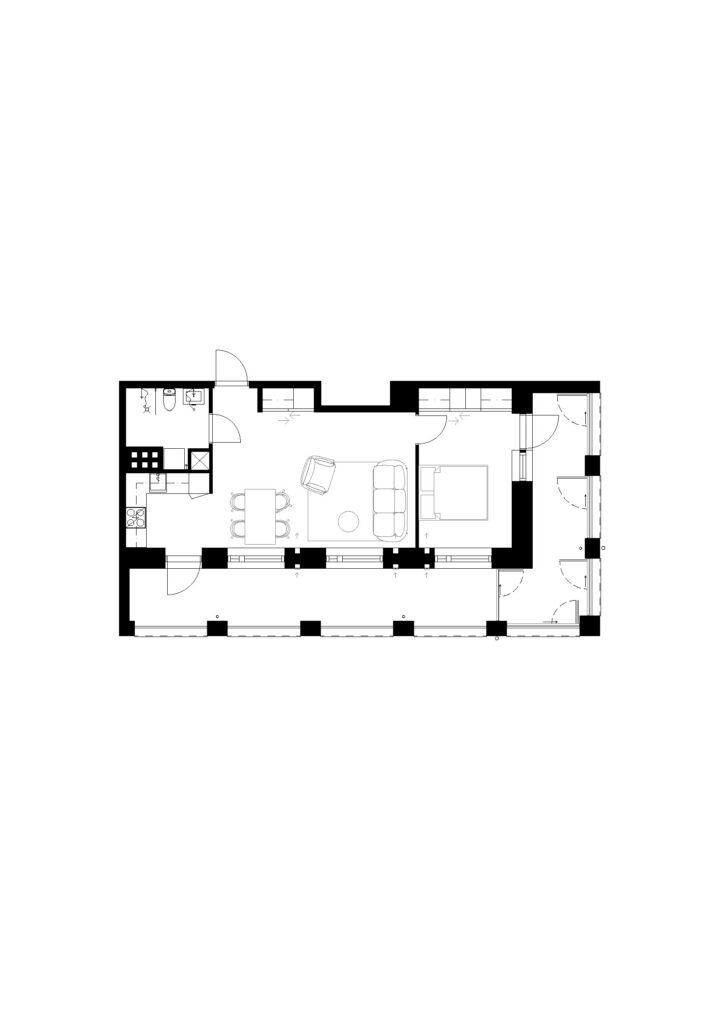

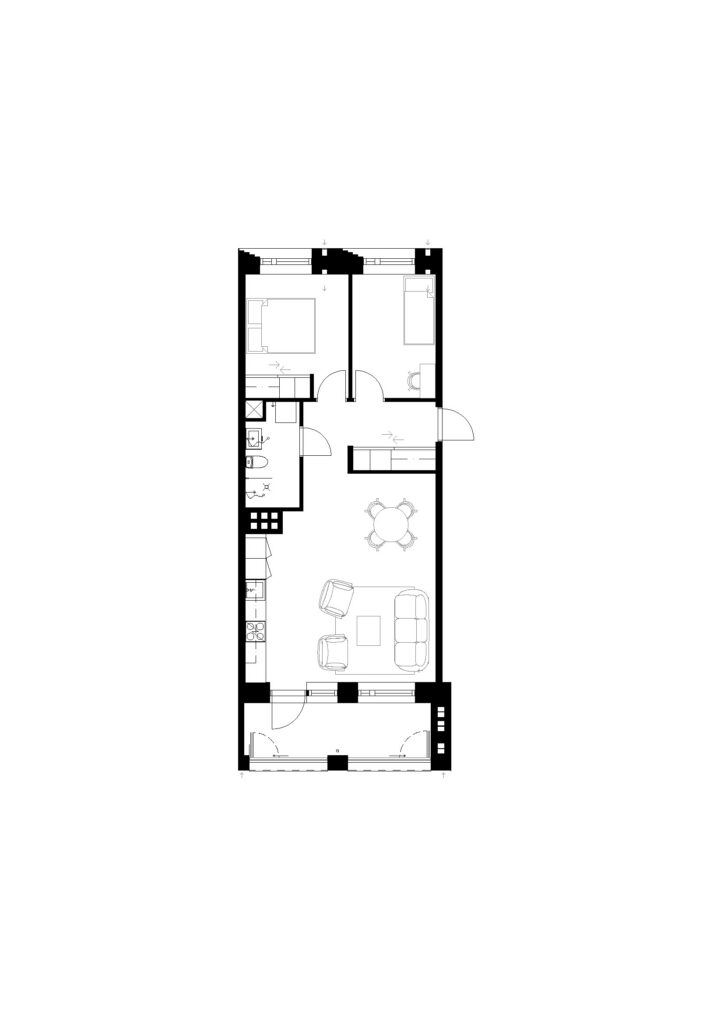

The project, however, is decidedly modern. It is generous to tradition, but not simply replicating those techniques for their own sake. It represents a clear and deliberate attempt at exploring the possibilities of constructing in monolithic brick today. Selective use of modern construction materials has played a supporting role in the performance of the building. The building’s concrete frame, for example, transfers the thermal mass far deeper into the building compared to wooden joists and beams used in historic brick construction. In place of the traditional lime-based mortar used in historic brick buildings, Helsingin Muurarimestari uses modern portland cement mortar, which offers far higher air-tightness performance. One particularly delightful innovation has been the integration of ventilation elements into the dividing walls of the balconies. While historic buildings have placed vents along the exterior facade, the current trend of large glazed balconies posed a particular challenge. Finnish fire safety regulations prevent the intake of air from glass-enclosed areas, and the architects have gotten around this by arranging the intake shafts in the dividing walls of the balconies—which the observant reader can see in the floor plans.

The return to natural ventilation and monolithic brick construction is not without its costs. To make up for the decreased thermal performance, the walls of Helsingin Muurarimestari are nearly double the width of a similarly performing multi-layered building assembly. This increases the building footprint significantly and made it particularly challenging for the architects to utilise the full building right up to the limits of the master plan. The novelty of the construction method and the coordination of labour it entailed led Avarrus to finance the building themselves, forming their own development company Kestävät Kodit Oy, as they were unable to find a developer who would back their project.2 Even in their position as developers, they had to acquiesce to the demands of the builders, opting for a cast-in-situ concrete frame around which the massive brick walls are built. This method guaranteed a degree of certainty to the construction process, allowing the bricklayers to work independently of the concrete floor slab casting teams. The architects estimate that at least 380,000 bricks were laid by a team of 16 brick layers and 16 apprentices.

Instead of debating the merits of traditional versus modern building assemblies, perhaps another lens through which to think about the project is its role as a housing product in its context. The Dymaxion house was not just born out of a fascination with new materials and manufacturing techniques but aimed to utilise the extra capacity of aeroplane factories in post-war America. Helsingin Muurarimestari might then be seen as a response to the cheap and fast construction that has come to define Helsinki’s rapid urbanisation over the past decade. Just like the critique of fast fashion, the project emanates a certain ‘buy it for life’ mentality. The inevitable carbon footprint of monolithic brick, not to mention the high economic cost of the building—over 20% more than its neighbours—is justified as an investment in the longevity of the building. In the long run, the building will require less maintenance and care, as it has fewer mechanical components and layers that will break down. Even the plumbing is designed with renovation in mind, with easily accessible pipes that run vertically through the building. The return on the building is therefore not measured in decades; it is measured in lifetimes. It presents itself as a strategic investment for those with the means and taste to appreciate it, and a morally just product that is lasting and durable. It speaks to the enduring precarity in our shared neoliberal condition, where individual consumer choices and the wise investment of one’s own capital become the determiner of success.

Indeed, the story of the project might be seen as a triumph of liberalised housing market, one where private innovation has delivered housing that fills a particular niche that is not being addressed by the ‘big players’. Yet Helsingin Muurarimestari is deeply rooted in the strong planning framework of Finland. The decreased thermal performance of the building is largely offset by the remarkable efficiency of the district heating network in Helsinki.3

Helsingin Muurarimestari itself was born as part of the Kehittyvä kerrostalo (Re-thinking Urban Housing) programme, which offers special plots for experimental and innovative development. Since most of the land in Helsinki is publicly owned, this enables the city to support pilot projects that the market is less likely to pick up on. These pilot projects in turn can feed into further advances in regulation and decision-making at scale. How might we build for a more sustainable and equitable future? Tradition or modernity? Simplicity or complexity? There are answers to be gleaned from Avarrus and Helsingin Muurarimestari, but it should also stand as a reminder that the climate emergency extends beyond the scale of individual consumer choices and into the conditions of their possibility.

LEONARD MA is a Canadian architect based in Helsinki who leads the architecture practice PUBLIC OFFICE. He is a member of New Academy and teaches at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

PHOTOS by Tuomas Uusheimo

PUBLISHED: MAJA 4-2024 (118) with main topic AIR

1 McHale, John (1962). R. Buckminster Fuller (George Braziller, 1962), p.17

2 ‘Kestävät’ has a double meaning as both sustainable and durable.

3 Building-scale passive solar and ‘net-zero’ strategies in the north inevitably require alternative (usually carbon-intensive) energy sources in the winter when heating demands are the most acute. District heating, on the other hand, is basically unparalleled in terms of carbon performance in a northern climate because it taps into the surplus heat from electricity generation; thus, energy production can be planned in a more holistic manner.