The exhibition ‘The City Unfinished. Urban Visions of Tallinn’ at the Museum of Estonian Architecture 22.01–16.05.2021. Curated by Johan Tali, design Raul Kalvo, graphic design Stuudio Stuudio, translation and proofreading Kaja Randam, Kaisa Kaer, Mirel Püss and Johan Tali. The research project ‘The City Unfinished’ conducted at the Faculty of Architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts takes a look at the big picture in the city of Tallinn and the concerns and opportunities of modern urban planning.

Visions of the Unfinished City

There is something decidedly elusive when we try to think about the city. When we think of a city, we might think of its monuments and landmarks, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, Central Park in New York, Old Town in Tallinn. We may think about a city and imagine the people who live there. The day-to-day situations of working and living, the gentle buzz of street life. Yet, cities also manage to change, new roads, new buildings, new people, and still remain recognizably a distinct entity. Separate, yet intertwined there is an idea of a city, and there are its physical manifestation and processes of existence. For planners, architects, and designers, the elusiveness of the city looms over every endeavour. A Sisyphean task of transformation, where every design, every intervention is a part of the endless task of realizing the city.

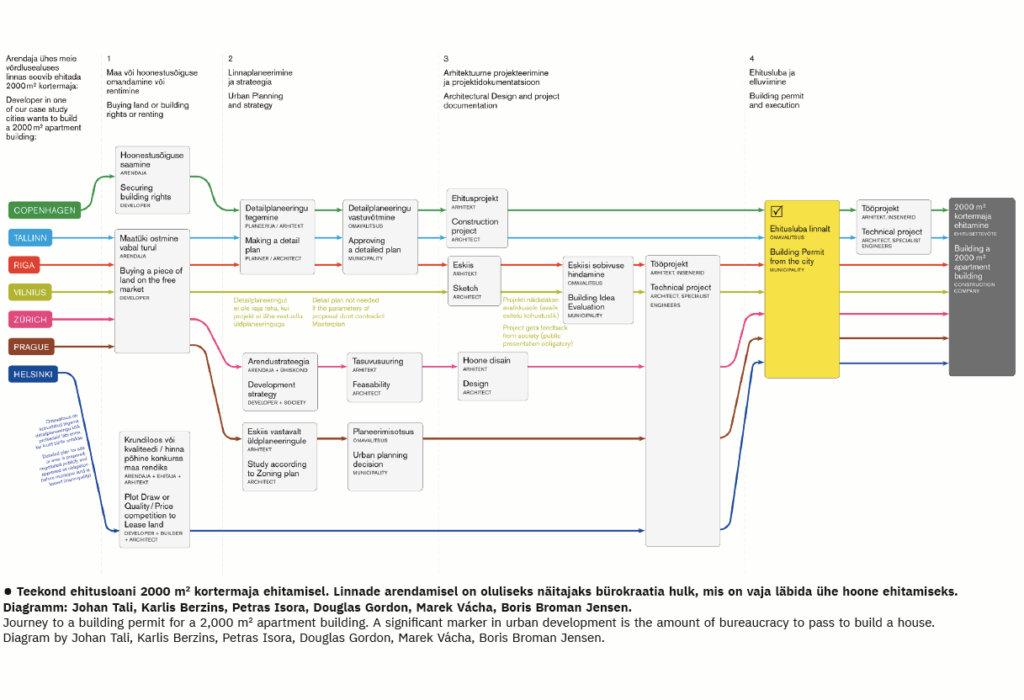

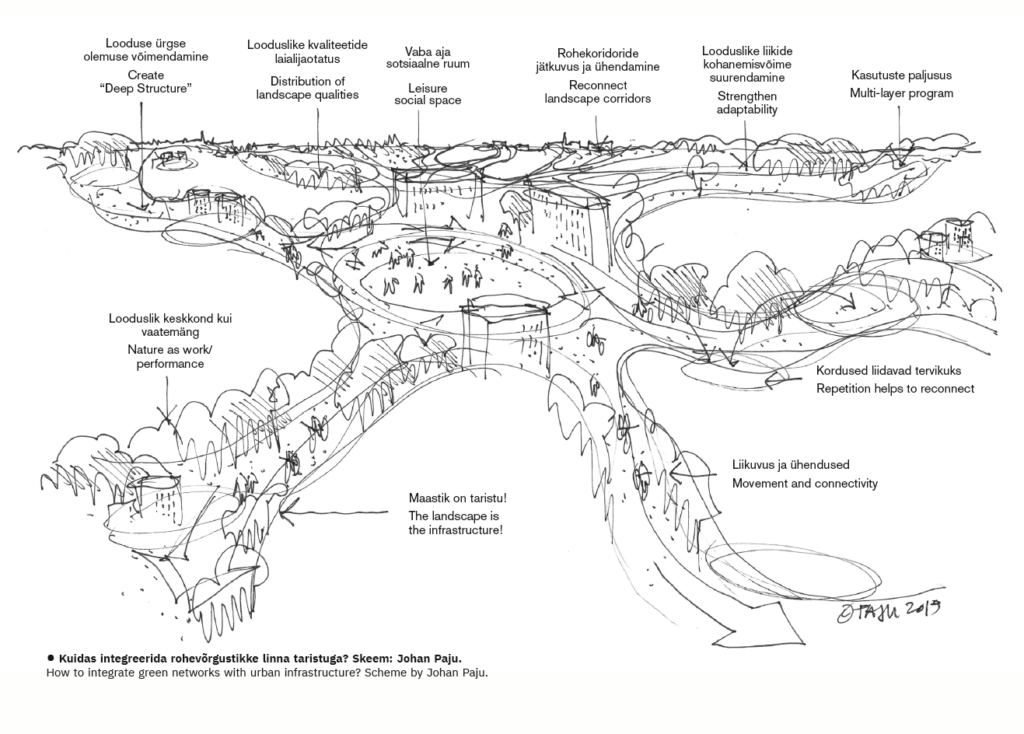

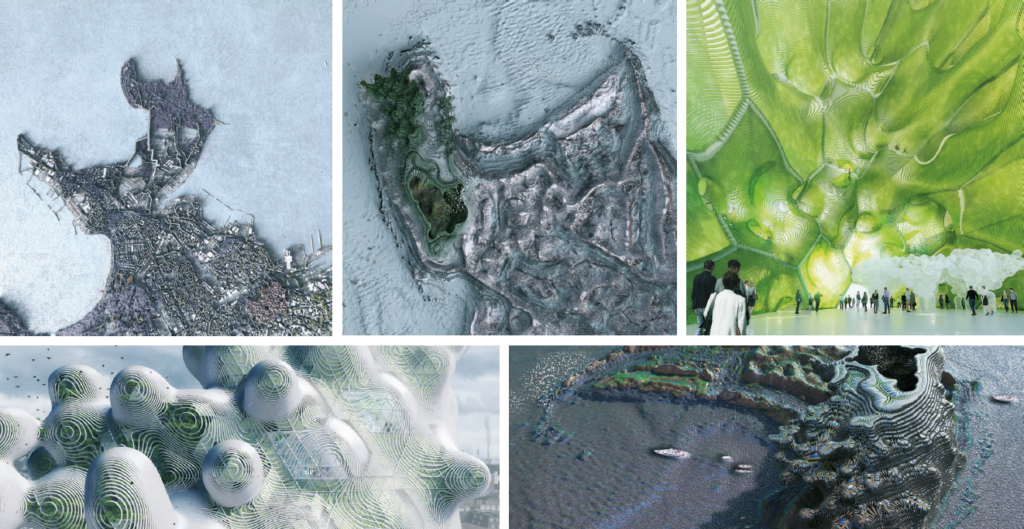

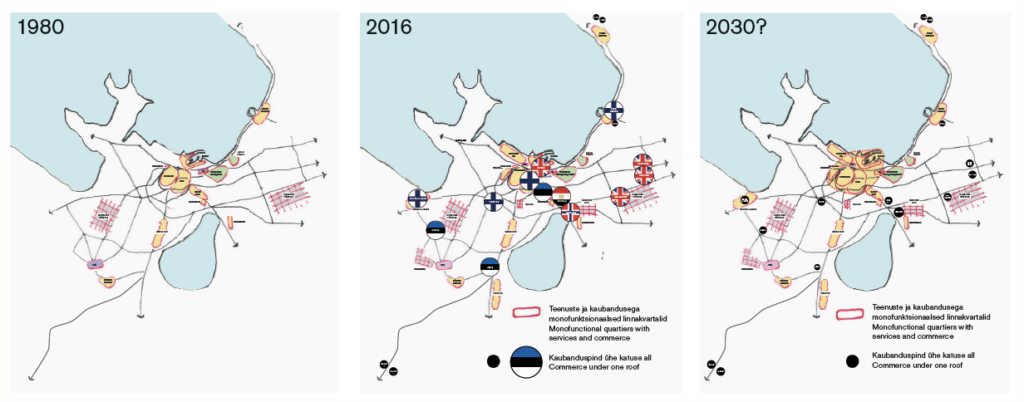

It is this dilemma that the new exhibition at the Museum of Estonian Architecture aims to address. We may recognize Tallinn as a city, what it may become, and the ways in which it might change, considered as part of a three-year project conducted in 2017-2020 by the Faculty of Architecture at the Estonian Academy of Art. Funded largely by E.L.L Real Estate (now Kapitel), the large-scale research initiative brings together an international group of researchers, practitioners, academics and students to consider the future of Tallinn. Grouped broadly into six main themes, the exhibition presents vision of Tallinn for 2050 and showcases research on topics ranging from comparative planning practices and computational tools to the future of prefabricated housing districts, green networks and city centres.

Taking Tallinn as the object of inquiry—a city without a long-term development plan, the ambition of the research is striking. Not only in making a case for the role of planning and design within the bureaucratic apparatus of the city but also in its aim to address the city as a whole. Comprised of analytical and demographic research on urban processes, morphology, and infrastructure, as well as student proposals for visions and interventions, the research provides a framework for a view on the city from the perspective of planning and design. One of the most striking inclusions is a new satellite photo of the city, a type of image that we take for granted now that it is so easily accessed. Yet, the up-to-date image provides a reminder of just how quickly Tallinn has changed within a few years. Even if the city is unfinished, it is certainly going somewhere.

Planning the Unfinished

So why the unfinished city? The exhibition and project tread carefully through a tense legacy of planning that has haunted architects and planners since modernity. The refrain goes something like this: If the city can be planned, then this plan also implies a point of closure, a finite conclusion that we all then must inevitably lumber towards. The aspirations of the Modernist planners, with their dreams of a tabula rasa on which new cities could be built in exacting detail, would be undermined by figures such as Jane Jacobs and her spiritual successors like Jan Gehl and Richard Florida. The totalizing gesture of the modernist masterplan and its claims of rationality were recast as an act of violence imposed from the top down, wiping away the complexity and vitality that made cities so exceptional in the first place. Contrary to the city as the manifestation of the will of the planner, there could instead be a more transparent, more democratic process of shaping the city. One that would in some way reflect the diversity and dynamism of those that inhabit the city themselves.

Yet, hopes for a more inclusive process of decision-making, perhaps by an enlightened bureaucracy responding to the lobbying of everyday citizens, would instead be replaced by the convenience of decision-making in the hands of the free market. The sanctity of private property and the investment of capital would become the key drivers of urban development. Stripped of any direct agency to design, fund and build, planners would take on an increasingly negative role by the end of the 20th century. Planning strategies would utilize zoning, restrictions and subsidies to attempt to direct investment in the city. ‘The City Unfinished’ therefore becomes a compelling device through which to discuss the possibilities of planning in Tallinn to a wider public. While there might not be a finite point of completion, there is much to be gained in breaking down the different factors that might inform how city development happens, and what might result if there were visions that these strategies could be directed towards.

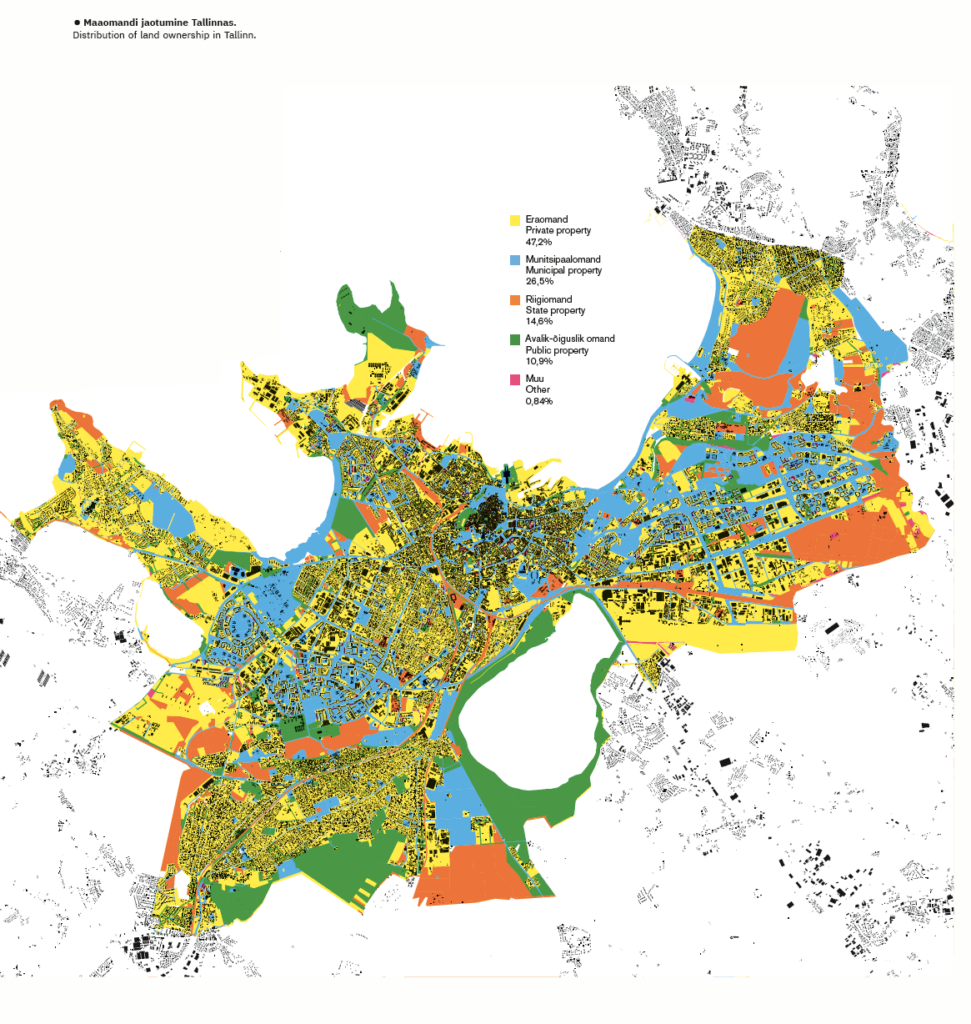

If there is a shortcoming to the exhibition, it is perhaps its optimism. Appeals to compelling and overlapping visions of community and neighbourliness, to lively and attractive urban space tend to feel flat without some vision of how we get from here to there and a consideration of who might get lost along the way. The hand a city has been dealt in this regard becomes vital, as can be seen in the comparative analyses of city planning practices shown in the exhibition. Helsinki, for example, has about 80% of its land in public ownership, allowing it to make strategic decisions on land use that would be hard to do in Tallinn. Global cities like Zurich, Copenhagen and Helsinki are attractive for investors, allowing them more bargaining power in restricting and shaping design decisions. Cities like Vilnius and Tallinn inevitably have less flexibility to resist and temper the demands of investors, lest they take their investment elsewhere.

In this sense, the ambition of the project to consider the city as a whole can be seen as not radical enough. A city is more than its streets and monuments or the inhabitants that live there. A city is a part of a society, a political system, a global economy. Can we confidently advocate for the benefits of green networks or public spaces as livelihoods grow increasingly precarious? When we are all too anxious and overworked, does the respite of public space become a salve on systemic conditions of inequality? The paradox of the city today is that as the agency of planners and architects to intervene in the city has diminished, the relationship between how the city is structured and how society is structured has grown increasingly intertwined. Although we may have a cosy vision of the city, one of neighbourhoods, home and communities, the city is also a city of assets. A city of investments and returns on capital that has grown even more elusive under the long shadow of financialized capitalism. The city of capital may appear as nothing new, after all its role in shaping that city has been well theorized. Concepts such as David Harvey’s spatial fix try to explain uneven development, where the spatial displacement of capital is a response to crises of over-accumulation. We might think of more colloquial narratives of developers wielding outsized influence to shape the city for their own gain, or of parasitic landlords extracting profits from an ever more precarious class of renters.

A City of Assets

To an outside observer, there would appear to be a degree of tension in the optics of a partnership between the Faculty of Architecture and one of the Baltic’s largest real estate developers and investors. The funding has not been insubstantial, nearly half a million euros over three years. A long time, long enough for E.L.L Real Estate to rebrand themselves as the more tasteful and ominous Kapitel. However, this partnership highlights the complexities of the city of assets and investments. Although not distributed equally, there has been a dramatic increase in access to real estate wealth. Although it might appear simply as oligarchs and private equity firms driving up housing prices, it is also the ease of access to mortgage loans, to home ownership incentives, and the low interest rate environment that have expanded the demand for real estate across all levels of society. In what Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper and Martijn Konings term the ‘Asset Economy’, home ownership is no longer a matter of stability but also a matter of speculation.1 We take a mortgage to buy a house or an apartment, but we also expect that investment to yield capital gains in the future.

Kapitel must be keenly aware of this situation. Although they wield large pools of capital and can initiate developments, they also confront a market environment where the gap between real estate prices and wages appears increasingly difficult to sustain. Some extraordinary developments in Tallinn are already over 5000 euros per square meter.2 Contrary to some popular narratives, addressing rising housing prices is not simply a matter of increasing the supply of housing. As real estate is increasingly viewed in speculative terms, it takes on the characteristics of a financial asset, whose market creates its own supply and demand.3 In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, real estate prices have quickly re-inflated, while wage gains have remained comparatively stagnant. With the influx of COVID-19 related stimulus funding and more quantitative easing, we can reasonably expect the value of assets to continue to increase.

The problem of both long-term plans and having no plans at all is that they postpone results into an indefinite future and it is here we encounter the political registers of ‘The City Unfinished’. On the one hand, yes, we should plan and hope that things might be better in the future. After all, building and urban development takes time, so we should plan for a better future. On the other hand, we could instead adjust our horizon not to the future but to today, to be even more radical in the political present, not just imagine how the city might be but to build the society now that will build that better city of the future. John Maynard Keynes, perhaps the preeminent economist of the 20th century, used the phrase ‘In the long run we are already dead’ to counter the apologists of the free market who during the interwar years were faced with mass unemployment would claim that things would work out in the long run.4 Keynes’ great contribution was to question the separation between politics and economics, recognizing that when markets affect the entire economy, they have systemic consequences.

I grew up in Vancouver, Canada, a city often praised for its long-term strategic planning in urban development. Vancouver deals with a similar planning environment as Tallinn, with limited agency in terms of initiating development and reliant on marshalling the forces of the free market. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the city underwent a building boom kickstarted by the 1986 World Expo. Canada’s political stability and Vancouver’s location as an international hub and gateway to the Americas and Asia Pacific made it an ideal location for foreign investment. The city developed several innovative policies to ensure a high quality of urban space. For example, in the downtown core, building on a given lot was limited to a certain percentage of the lot area. This would ensure that developers would build attractive public and green spaces at the street level, while also maintaining view corridors to the surrounding mountains. Other initiatives such as protected green areas and one of North America’s pioneering cycling networks helped to cement Vancouver as one of the most liveable cities in the world at the turn of the millennium.

Yet today, housing affordability has become a major issue in the city. The great irony is that many can now no longer afford to live in one of the most liveable cities in the world. This has proven to be a particularly difficult knot for policy makers to untie, as real estate has been so thoroughly embedded in the economy. In 2019, over 50% of Canadian GDP was from real estate transactions. Any drop in housing prices or slowdown in the real estate market would bring catastrophic results. Ham-fisted attempts to address the problems of housing unaffordability in the major Canadian metropolitan areas through first-time buyers’ discount on mortgages or increasing the amount of mortgage debt that is guaranteed by the government has only further spurred the rise of real estate prices. Increasing provisions for social housing does not appear to be a simple answer either, as they are indexed to market rents and still trend upwards while also excluding portions of the population from speculative real estate gains. As we see even in countries with robust social housing programs such as Austria, many still choose to invest in real estate because it becomes a gateway to future wealth.

As we look over the visions of Tallinn as the Unfinished City, we see cities of processes and data, cities of attractive green networks, lively urban centres and high-quality design. But we should also ask ourselves, will this be a city of real estate agents? Or will it be one where we can live and work with dignity at all level of the economy? How might the political lines be drawn to ensure a more equitable and just future for the city and what alliances need to be built to make this possible? What we should be sceptical of is not the generosity of Kapitel in funding this project, but to wonder why this level of funding does not come from anywhere else. While there are endless grants and funding for research that produces tangible results at the urban level—reducing carbon emissions, smart city technologies, tools for mapping and data analytics—those that offer a chance to theorize the very nature of planning are few and far between. More than anything, ‘The City Unfinished’ offers a chance to consider the premise of its beginning. What is the role of planning and what are its limits and agencies?

As with all design-based research, it is easy to be caught up in the possibility of the visions proposed by ‘The City Unfinished’, or the avenues opened up by its more descriptive research. Success in this regard seems predicated on the enthusiasm of the discussion around the exhibition or the reach of the research in shaping policy decisions. Yet, if we consider the support needed from stakeholders, investors, bureaucrats and politicians to realize these visions, we begin to grasp the limits and agencies of planning itself. Perhaps the most important result of ‘The City Unfinished’ is to highlight just how much work there is to be done, that it takes more than the will of the designer to build the city.

Such cynicism might appear unproductive when it seems there is a need to make a case for planning in the first place, but it highlights the need to be unwavering in confronting the systemic conditions of the production of the city. Navigating these conditions requires an adjustment of the horizon. We don’t just need more designs and visions for the city as a whole—to try and finish the unfinished city again and again, but we also need to situate the city within a broader systemic and socio-economic context to build the coalitions of support needed to realize those visions. The work of architects, planners and designers is not an end to itself, but can become a powerful catalyst to engage with others such as economists, labour organizers, sociologists, artists and scientists. We can begin now, or we can hope things work out in the long run. After all, with or without us, the unfinished city will still be there, but we can help to build the society that will forge it anew.

LEONARD MA is a Canadian architect based in Helsinki. He is a member of New Academy and teaches Urban Studies and Architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts. His research focuses on neoliberalism, financialization, and the legacy of the welfare state, and has been published in E-flux, The Avery Review, and AA files.

HEADER photo by Evert Palmets

PUBLISHED: Maja 104 (spring 2021) with main topic What’s happening?

1 See, Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper and Martijn Konings, The Asset Economy (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020).

2 https://www.kv.ee/korter-noblessneri-sadamalinnakuskorter-sisaldab-j-3316927.html?nr=2&search_key=1194724e475ed255defd4422bfe0a097

3 See, Denise DiPasquale and William Wheaton, ‘The market for Real Estate Assets and Space: A conceptual framework’, Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, v20, no. 1 (1992): p. 181–197.

4 See Geoff Mann’s excellent book on Keynesian political thought ‘In the Long Run We Are Already Dead’ (London: Verso Books, 2017).