The order of nature is complex, interesting and beautiful. However, mankind’s understanding of order and beauty tends to be somewhat primitive and thus we are increasingly losing the sense of balance that could direct our activities. Green areas are meant for public use, but in reality they have become neatly mowed lawns that people never walk on and that we have consequently made unsuitable for other living organisms.

The Era of Green Deserts

The recent Club of Rome memorandum “Come On!” states that there is no longer any free space in the world that has not been taken into use by man. That is also the case in Estonia. Even nature reserves and natural parks are in active use either by tourists or scientists. The only difference lies in the mode and intensity of the use. More intensive use is usually accompanied also by more intensive maintenance. If you want your field to yield a good crop, you need to plough and fertilise it, fight weeds and pests. Similarly, cultural grasslands require careful maintenance. However, there is one type of grasslands in which the intensity of maintenance and practical use do not always go hand in hand. These include a vast majority of the lawns that we often call green areas. If the lawns in golf courses, sports and playgrounds are indeed walked and run upon, then most green areas are merely low-cut lawns that nobody ever sets their foot on. In our present era of lawnmowers and garden tractors, the surface area of such lawns has grown considerably. And the given lawns have become a part of a serious ecological problem. Intensive agriculture has brought about monocultures – these days it’s impossible to find wild flowers in the fields, for instance, our national flowers cornflowers or poppies. There are also few blooming plants on grasslands. This means that our nature has become poorer, our biodiversity has drastically diminished. We see that the Estonian towns and rural areas have indeed grown greener, but they no longer bloom. This means that there is no longer any place for bees, bumblebees and butterflies on our fields, meadows and urban green areas. Without noticing it, we are fighting a – very successful – war against flowers and butterflies. And where there are no insects, there are no birds, spiders and other insectivores either. Thus, the majority of our lawns-green areas can actually be called green deserts. Thus, also Estonia has reached the deepening ecological crisis, the rapid decrease of biodiversity posing a huge threat to the life on the planet Earth. Most people unfortunately have not comprehended that.

The situation where we find ourselves firstly requires some analysis. We must make sense of the reasons that have taken us to the crisis and then look for possibilities to come out of it or at least alleviate it. There are several reasons for the decrease of biodiversity, the growth of green deserts. First of all, the politics with its capitalist ideology considers nature valuable only in terms of the profit it yields, crops in the field, timber in woods etc. We can only hope that the ecological crisis will bring about some changes in the agricultural and forestry policies so that in addition to profitability and productivity, also ecological indicators such as the variety of species and biodiversity would be considered more important. However, in case of lawns and green areas, the main role is not played by grand political decisions but primarily psychological factors that, in turn, are determined by our biology, culture, education and habits.

I’m inclined to think that the sprawl of green deserts in Estonia is, on the one hand, caused by our post-Vargamäe attitude to nature, on the other hand, there are the vivid memories of manor parks and gardens that in the 19th century became a paragon for local people living in farms as well as in cities. Our ancestors fought long battles against the forest, brushwood and unwanted plants that tended to take over fields and gardens. Much like against bogs that had to be conquered to obtain arable land. It was equally arduous to establish a small garden where flowers and decorative bushes could come to the fore against the background of a low-cut green lawn. The peasantry obviously could not establish extensive parks and respective lawns, this still remained the privilege of the lords who could afford cheap labour.

Now everything has changed completely. Almost every family has access to carts drawn by dozens of horses, i.e. cars, the work of dozens of scything hands is done by lawnmowers, garden tractors and trimmers, and similarly pesticides that can easily destroy everything that you do not wish to see in your garden. In some sense, we are wealthier and mightier than the former lords of the manor. We wish to enjoy this wealth and power, present it to ourselves and others. In the pair of opposition “nature – culture”, we firmly side with culture. We do not like a natural untended landscape or forest, we want to “tidy up” our surroundings, clean it from everything wild and self-generated, brushwood, shrubs… Although we do appreciate butterflies as well as the song of nightingales and warblers, we do not usually understand that the given beautiful winged creatures need brushwood, untended areas with nettles and mugworts, as well as dandelion seed heads that goldfinches and linnets could feed on. There is no food for them in green deserts. The situation is particularly sad when the lawns have been cut only a centimetre or two above the ground just to gloat over one’s mastery of nature. Such mowing means immediate death to the small creatures who have found a safe haven for themselves in the grass.

We want to “tidy up” nature. I once even happened to read someone’s opinion that forests are in a mess with too many bushes and shrubs scattered. And a low-cut green desert of a lawn is indeed very tidy, only surpassed in tidiness by artificial turf. Here our understanding of order comes to be in severe conflict with the concept of natural order. Nature is not unruly or chaotic, its order merely surpasses our imagination in complexity. I have found about twenty different species in a square metre of untended grass and about the same number of various insects. And this is only the part above the ground, the underground life is considerably more versatile: a handful of soil includes billions of micro-organisms of about ten thousand species. These micro-organisms – bacteria, fungi, viruses live and function together with plants, insects and larger animals, they depend on each other and together form what we call the eco-system. The system of all the eco-systems of the planet is called the biosphere. Man can generally change ecosystems only by decreasing their complexity, and now the human impact has come to simplify the entire biosphere, with a new period starting on Earth – the Anthropocene. The simplification of ecosystems is bound to be accompanied by negative changes, crises, massive extinction and disasters. The simplification of the biosphere will probably lead to such serious changes that man’s existence on this planet may be called in question.

If the lawns in golf courses, sports and playgrounds are indeed walked and run upon, then most green areas are merely low-cut lawns that nobody ever sets their foot on.

Our green deserts are supposed to take after the lawns in the Western Europe, in England in particular, where they grow nothing but grasses. This is not correct. I have never seen a lawn in England without daisies. Something that our ardent fans of “the English lawn” have even fought against. In the Western Europe it was understood already some decades ago that urban parks, green areas, lawns and gardens can help us to maintain and restore the natural character and biodiversity that we have lost with the intensive land cultivation. When I think about it, I’m always reminded of huge unscythed grasslands in Hyde Park, the dandelion seed heads swaying in the city centre of Frankfurt and the tiny fences around young trees in Paris protecting the nettles, thistles and dandelions burgeoning around them. Similarly, I’m reminded of the request by Francis of Assisi to leave a small plot of land in convent gardens for everything that God has planted there. It is high time for us to understand what Francis understood already 900 years ago and people in Germany, France and elsewhere understood at the end of the previous century. The stunted clearings are not too pleasing to the eye either. However, they could provide a considerable balance to the intensively monocultural meadows and grasslands, they could be reserves, habitats for endangered species. And we would help the ecosystems to remain sufficiently complex and stay in the order that a religious person would call divine and regard with solemn adoration. This is where science, ecology and religion come together which is also movingly expressed in the encyclical of Pope Francis “Praise be to You” (Laudato si) that was recently published in Estonian.

It would be naturally unfair to claim that the spread of green deserts is only due to people’s backward understanding of orderliness, European character and beauty. The triumph of lawn tractors also has practical reasons. Now that we no longer need to cut, dry and store hay for our animals with utmost care, it has become something that many of us have no reasonable use for. So, the easiest way is to give up haymaking altogether and let the machine chop it into a fine fertiliser. There are alternatives, primarily the collection and composting of cut grass, but it may sometimes be even a more laborious process. Much like its transportation from smaller plots and storage for animal fodder. But with good will and comprehension of what Juhan Liiv expressed as “Uniformity kills, life lies in diversity”, we could find a solution also to the given problems. Collecting the cut grass in and around cities should not be an overtly difficult issue. Hereby I’m reminded of a plot of land near Lõunakeskus in Tartu that used to be yellow with dandelions in spring and blush with clover in summer. The given beauty and diversity have now been destroyed and taken over by an ever-expanding green desert with almost no blossoms. Naturally with no butterflies, bees and bumblebees either. The green desert is not visited by people. This is the deadly uniformity. That we should finally stand up against. In word and action.

JAAN KAPLINSKI is an Estonian writer, poet, translator, culture critic and philosopher.

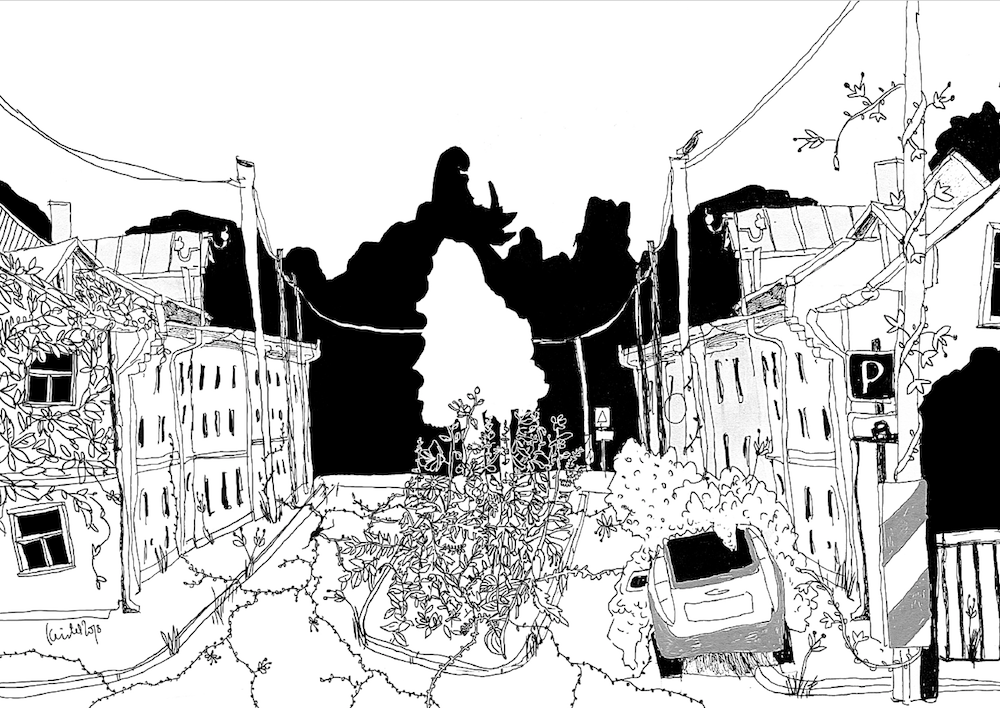

ILLUSTRATIONS by Kristel Sergo

PUBLISHED: Maja 95 (winter 2019), with main topic Drift