Acting in accordance with statute of the heritage conservation area in a shrinking city like Valga is impossible. Investing in listed buildings (architectural monuments) and buildings located in heritage conservation areas should be promoted in shrinking cities when the support measures for various fields are developed.

A 120-year-old apartment building located in the centre of Valga near St John’s Church at Kesk 20 was demolished this September, as it had become a danger to its surroundings. The disappearance of an old building from the most valuable site in the heritage conservation area in Valga is the result of a process in the city that has lasted for a long time.

Valga’s two periods of growth

There are many abandoned and underused buildings in Valga, especially in the city centre. Although the negative demographic developments in Valga are no different from those in the majority of Southern Estonian cities, the situation in Valga is objectively more complicated.

The reason for this lies in the specific development of the city. Historically, Valga has experienced two periods of rapid growth, while at other times it has lost its population. The connection of the city to the rail network and the resulting development of industry in the last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century brought about the first period of growth: the population increased from 2473 people in 1867 to 14,179 people in 1919 [1]. The city was split in two when Estonia and Latvia regained their independence, and exports to Russia decreased considerably. After World War I the city grew as a result of the increase in its administrative territory and continuing urbanisation, but this trend turned during the massive recession and the population decreased from 14,746 in 1929 to 10,842 in 1934 [1]. The population continued to decrease until World War II.

The city started growing again in the 1960s and 1970s. Valga became an important industrial city and military base due to the opening of the Soviet market. Both of these activities had a significant impact on population growth: 13,354 people lived in Valga in 1959, but the population had increased to as much as 18,474 in 1979 [2]. Estonia’s regained independence meant that the Soviet army left Valga, and the city’s industry, which had depended on the Soviet market, disappeared. The city’s population decreased by 3172 people between 1989 and 2000 as a result of these changes. These people leaving is why the situation in Valga is somewhat more complicated than in other similar cities in Southern Estonia. 12,452 people lived in Valga as at 1 January 2017 [3].

Plenty of unliveable residential premises, almost no high-quality ones

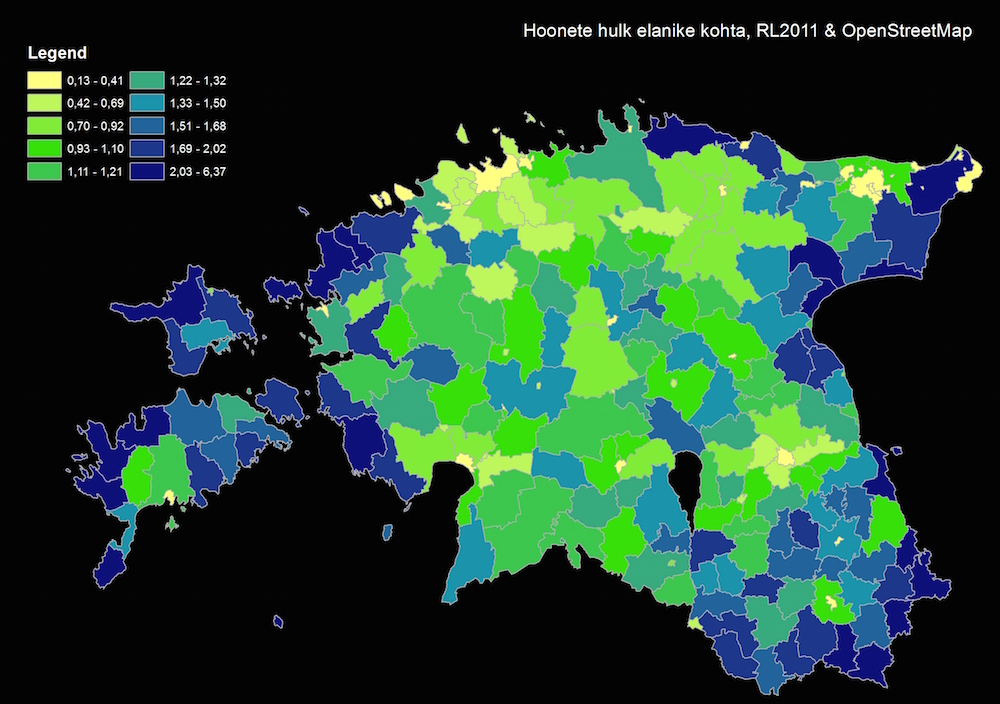

The size of the city still corresponds to the needs of the population the city had 30 years ago, but the number of people has actually decreased by a third. No active use can therefore be found for more than a quarter of the city [4]. This problem is felt most acutely in the occupancy of apartment buildings. 45 of the 379 apartment buildings in Valga have been abandoned, and less than half of the apartments in 34 of them are occupied [5]. The abandoned or underused apartment buildings mostly date back to the first period of growth: they are two-storey wooden buildings, usually without central heating, bathrooms or sewerage. Wooden apartment buildings can be found in various districts of Valga, but most of them are located in the heritage protection area in the centre of the city. The building at Kesk 20 that was demolished in September was one of these apartment buildings. The occupancy rate of panel buildings from the second period of growth is higher, because the apartments in these buildings remained vacant after the departure of the Soviet army in the early 1990s and many people living in the wooden houses moved to these newer, more convenient apartments.

The larger share of unused residential premises on the market lowers the prices of property. The average price of an apartment in Valga is less than 150 euros per square metre [6]. This low price does not allow owners to sell their properties or use them as collateral for loan agreements. The private sector is not interested in investing in renovating properties or building new apartment buildings. The result is the predominantly low quality of residential premises and the lack of quality (rental) apartments, although the need for them exists. Both public institutions (city government, hospital, schools, etc.) and private entrepreneurs have struggled with the lack of specialised workers for a long time. However, the lack of decent dwellings makes attracting specialists to Valga very difficult. The public sector must intervene in the free market, at least temporarily, in order to improve the situation. The state’s new measure of municipal rental apartment buildings is the first step in this direction [7].

Difficult choices

When the quality of life in an apartment building starts deteriorating, those who can do so move out. Apartment owners with the lowest income remain in the building, but they cannot afford to pay for maintenance and the building becomes uninhabitable. Valga City Government offers these people either social housing or the opportunity to exchange their apartment for another in a more sustainable building. The city government prepares a technical expert analysis of an empty building that declares it unsuitable for exploitation, withdraws the right of use from the building and orders an expert opinion on the building. The value of an apartment without the right of use is zero and the value of the plot does not exceed the demolition costs of the building, which means that the value of the property becomes negative. The apartment owner is left with two options: they can gift their apartment to the city, or participate proportionately in covering the demolition costs. Six abandoned apartment buildings have been demolished in Valga in the last three years.

The fate of the building at Kesk 20 is a prime example of the process described above. The city government evicted the last residents two years ago when conditions in the building had become so bad that it was no longer habitable. Irrespective of issuing precepts and talking to the owners, the city government failed to acquire all of the apartments, as they were encumbered with debts and mortgages. The roof of the building at Kesk 20 was leaking and its condition was deteriorating rapidly. The city government made all of the preparations required for demolition as described above and requested a permit from the National Heritage Board. The National Heritage Board advised the city to preserve the building and, after lengthy discussions, refused to issue the permit in 2017. The building remained standing at first, but the citizens continued to demand its demolition. Parents of students from the music school next to the building also started raising their voices in early September, and the police sent a memo asking for the building at Kesk 20 to be demolished, as they had repeatedly been called out to the building. Unfortunately, it is very difficult for local governments to justify the use of public funds for the renovation of a privately owned building. The city government had two options: wait for the building to collapse or demolish it. On 22 September 2017 the city government implemented immediate substitutive enforcement without a precept for the demolition of a dangerous building [8].

Bottlenecks in heritage conservation

Demolishing a building at the heart of a heritage conservation area is an extreme measure, which shows the difficult choices faced by the city government and the National Heritage Board in the centre of Valga. Only 64% of the plots in the heritage conservation area, and even fewer listed buildings (53%), are in use [5]. The condition of the buildings has deteriorated since the declaration of the heritage conservation area in 1995. Unfortunately, the responsible authorities – the city government and the National Heritage Board – cannot actually control the decrease in the population of Valga.

The story of the apartment building at Kesk 20 highlights the bottlenecks in the current heritage conservation system in Valga. Let us take a closer look at them.

Objective of conservation

The statute of the heritage conservation area of central Valga state that the objective of conservation is to preserve the city centre as an urban whole as it had developed historically by the 1940s [9]. As Valga was already in the state that followed the period of urban explosion by then, the objective of preserving the city’s structure as it was at the time seems too ambitious.

Impact of buildings on surroundings

The same statutes declare the need to preserve housing in the historical city centre [10] to the maximum and for as long as possible, but no deeper meaning has been given to this attempt. In autumn 2016, Valga City Government carried out a survey of people living in the city centre as part of preparations of the general plan of Valga in order to clarify the values of the people and their views on the present and future of the city centre. The ramshackle buildings in the city centre were the main factor that forced respondents to move away from central Valga. A city centre filled with underused and abandoned buildings worsens people’s attitude towards the city, their pride in the city decreases or disappears and this in turn reduces their readiness to contribute to the development of the city and the conservation of heritage. The negative impact of abandoned buildings becomes magnified. Assessing the value of each building located in a heritage conservation area separately is not justified, and we must also consider the impact of the buildings on the surroundings.

Value of buildings

In general, the National Heritage Board finds that the demolition of a historical building in a heritage conservation area is impermissible if the building can be preserved [11]. When the permit for the demolition of the building at Kesk 20 was applied for, the National Heritage Board assessed the historical and architectural values of the building and its importance in urban space [12]. They said that they could not rule out that someone might want to save the building in the future, and therefore refused to issue the demolition permit. However, this approach seems inadequate in the context of a shrinking city. In addition to historical and architectural value, it should be assessed whether the building is in use and what the likelihood is of the building being used again during its lifetime. The latter is significantly influenced by the technical condition and ownership status of the building. The potential for use of the building on Kesk Street was not assessed.

Prevention of buildings becoming run down

It took several years for the apartment building on Kesk Street to become as run down as it did. The decline of the building accelerated considerably when the roof started leaking and the remaining owners were unable to get it fixed. The local government has the right to intervene if a building is a danger to its surroundings, but the gradual destruction of a building is not sufficient for intervention. Preventing destruction is the duty of the National Heritage Board, which it is failing to perform, at least in Valga. In order to save buildings, it must be possible for the National Heritage Board to temporarily fix the roof in addition to applying pressure on the owners, even if the owners are being negligent or are opposed to the idea.

Guiding local government

The city government had reached a dead end regarding the building at Kesk 20. Demolition of the building was prohibited, but the National Heritage Board did not explain how the city should proceed in this situation. The National Heritage Board must understand the consequences of its decisions.

There is no simple solution to the conflict between society’s need to conserve architectural heritage and to adapt a shrinking city according to the expectations of its current population. Heritage conservation and urban planning specialists all over the world are trying to figure this out [13]. The city government and the National Heritage Board must act as partners in improving the condition of central Valga. The people of Valga want to see a stronger National Heritage Board that is present in Valga: the kind of board that prevents the destruction of buildings before they become so run down that they have to be demolished; the kind of board that advises and understands people who have not moved away despite the impact of shrinking; the kind of board that supports the development of central Valga. In order to be able to meet these expectations, the National Heritage Board definitely needs more resources.

Essential cross-sectoral cooperation

Urban planning in a shrinking city faces two main tasks: adapting the size of the city to the needs of the citizens; and reviving the city centre [14]. This has to be done in conditions where the public sector is the biggest investor. Using taxpayers’ money for the right things calls for an assessment of the impact of support on the shrinking urban space when the various support measures are being developed.

In Valga, there are many examples of cases where this was not done. The biggest investment made in Valga in recent years was the new Valga County Vocational Training Centre financed by the Ministry of Education and Research, which was built on undeveloped municipal land on the outskirts of the city in 2011. The buildings in the city centre previously used by the training centre mostly remained empty and are falling apart. In the case of Valga State Upper Secondary School, which was completed in 2016, and the new building of Valga Priimetsa School [15], Valga City Government managed to get the state to invest in monuments in the city centre. This is despite the fact that the status of a monument was a factor that made the projects more difficult and was not favoured by the financier. The previously mentioned measure of municipal rental apartment buildings initially also supported the construction of buildings only belonging to energy classes A and B. After lengthy explanations, a variant was finally found that also allows old and vacant buildings in the city centre to be repaired. In a situation where public funds are limited, we should prefer investments in monuments and buildings in heritage protection areas instead of building new buildings on the outskirts of the city.

JIRI TINTERA is the city architect of Valga and a graduate of the Czech Technical University in Prague (2007). He is currently completing his PhD at Tallinn University of Technology, where he studies shrinking cities and abandoned and underused areas.

REFERENCES:

[1] Tammekann, A., Luha, Ä. and Kant, E. (1932). Valgamaa maadeteaduslik, tulunduslik, ja ajalooline kirjeldus /Geographic, Commercial and Historical Description of Valga County/, Eesti kirjanduse seltsi kirjastus, http://www.digar.ee/viewer/et/nlib-digar:276057/250298/page/505

[2] Statistics Estonia (2017). Ajaloolised nopped /Historical Tidbits/, http://www.stat.ee/pp-ajaloolised-nopped

[3] Statistics Estonia (2017). RV0282 rahvaarv, 1. jaanuar ‒ haldusüksus või asustusüksuse liik /RV0282 Population 1 January ‒ Administrative Unit or Type of Settlement Unit/

[4] According to a survey carried out by Valga City Government in 2014, 80% of all usable plots (which have/had been developed or named for development in the general plan) are in use. Since the area of abandoned or underused plots is bigger than average, 72% of the area of usable plots is currently in use.

[5] Survey carried out by Valga City Government in 2014.

[6] According to the transactions database of the Land Board, the average price of an area unit in transactions with apartment ownerships (residential premises) in Valga from 1 January-31 December 2016 was 139.03 euros/m2.

[7] Investment grant for the development of housing stock for local governments, managed by KredEx.

[8] § 28 of the Law Enforcement Act.

[9] § 5 (1) of the Statutes of the Heritage Conservation Area of Valga City Centre.

[10] § 5 (2) 5) of the Statutes of the Heritage Conservation Area of Valga City Centre.

[11] For example, Minutes no. 363 of the meeting of the Approval Committee of the National Heritage Board of 26 September 2017, reg. no. 1.1-7/2186-1.

[12] Decision of the Expert Council of Architectural Monuments of the National Heritage Board of 3 April 2017, reg. no. 1.1-7/438-3.

[13] For example Mallach, A. (2011), Demolition and preservation in shrinking US industrial cities, Building Research & Information (2011) 39(4), 380–394

[14] Sánchez-Moral, S., Méndez, R. and Prada-Trigo, J., Resurgent Cities: Local Strategies and Institutional Networks to Counteract Shrinkage in Avilés (Spain), European Planning Studies, 2015 Vol. 23, No. 1, 33–52

[15] The measure “Streamlining the School Network” of the Innove Foundation. Valga Priimetsa School will be moved from its current building (constructed in 1967) on the outskirts of the city to a monument in the city centre.

Photos Paco Ulman.

Article is published in Maja’s 2018 winter edition (No 92).