Mihkel Tüür writes about the wooden slat house that he built on the island of Muhu fifteen years ago.

Islands as spaces that are separated from the mainland by sea are ideal for finding isolation. At the same time, you can go anywhere by sea, so the relations that an island bears to its surroundings are simply of a different kind. In a similar way, every house is (and has to be) fully isolated from its surroundings with air and thermal insulation. A house on an island, then, provides a kind of super-isolation, refuge for a true escapist—first you isolate yourself from the world with the sea, and then you isolate yourself from your immediate environment with the building. A house on an island is like a frame within a frame.

Bridging

In terms of ancestry, one side of my roots lies on the island of Muhu, whereas the other side is of Mulgi origin. In the 19th century, my Muhu ancestors lived in Koguva village, and it is said that they operated a sailing boat named Uisk there, carrying mail and other things between Saaremaa and Muhu, until a dam was built in 1896 that bridged the two islands. Since the building of the dam, it is as if the island of Muhu has become a part of Saaremaa—but conceptually and administratively, Muhu is still a separate island, regardless of the dam.

Sometime around 1905, one Mihkel Tüür (there are at least six buried in a graveyard on Muhu) moved with his family from Koguva to Kondimäe farm in Rannaküla, a village on the other end of the island. In this farm, this branch of my family lived until the 1980s, when the farm was abandoned and its buildings decayed. In the course of property restitution in the 1990s, Kondimäe farm was returned to my father, and the plot now filled with overgrown ruins waited for a new use. In 2008, I felt that spending summers in the city with children can be quite a torment, and thus, I got the idea of building a wooden hut on the Kondimäe plot. I had spent my entire conscious life on the mainland, and being on an island was a completely new experience for me—after all, in Soviet Estonia, you could go there only about twice a year, and only with a special Saaremaa permit, which was thoroughly checked in the port by border guards with dogs. Moving around on the island now, however, it became clear that the locals know me better than I do, because they had known my ancestors whom I myself had never even seen. It was a strange, but very pleasant process—getting to know yourself again through your roots.

According to one telling, the whole history of architecture can be seen as a history of bridging, i.e., isolating a sufficiently large space from the outdoor climate with as simple means as possible, and then bridging this space, as has been convincingly shown by Bill Addis in his Building: 3000 Years of Design, Engineering, and Construction. It is a kind of weird architectural paradox that the very same process simultaneously connects and isolates.

Grandfather’s board-drying stack

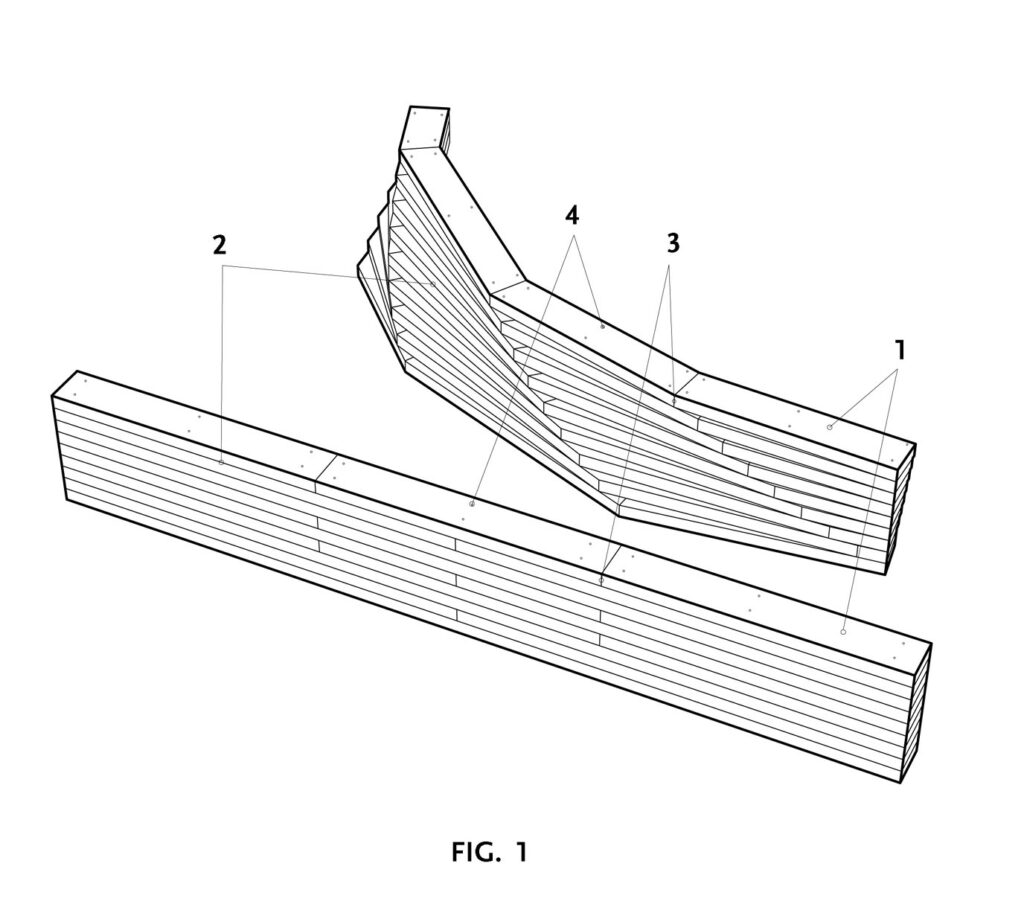

When we were children, me and my siblings witnessed how my father and grandfather received a bunch of wet boards from the sawmill. These were then heaped in a spaced out stack to dry. A grid of six boards was formed on the ground—three boards in one direction and three in the other. The stack was grown layer by layer until it was about two metres high. Such a stack came into existence in a couple of hours, and all of a sudden, it was as if there was a new four-room house in the middle of the yard, which you could climb into by the boards. Compared to the ten-years-long construction process of my father’s summer house, it seemed like a very efficient way to build—simply stacking up the materials. I decided to use the same principle in building my house on Muhu. But how to bridge that space? I decided to refrain from bridging the house at all—I simply brought the stack together at the apex, as a knitter would do with the heel of a sock, and thus, the space was enclosed with a false vault.

Wind

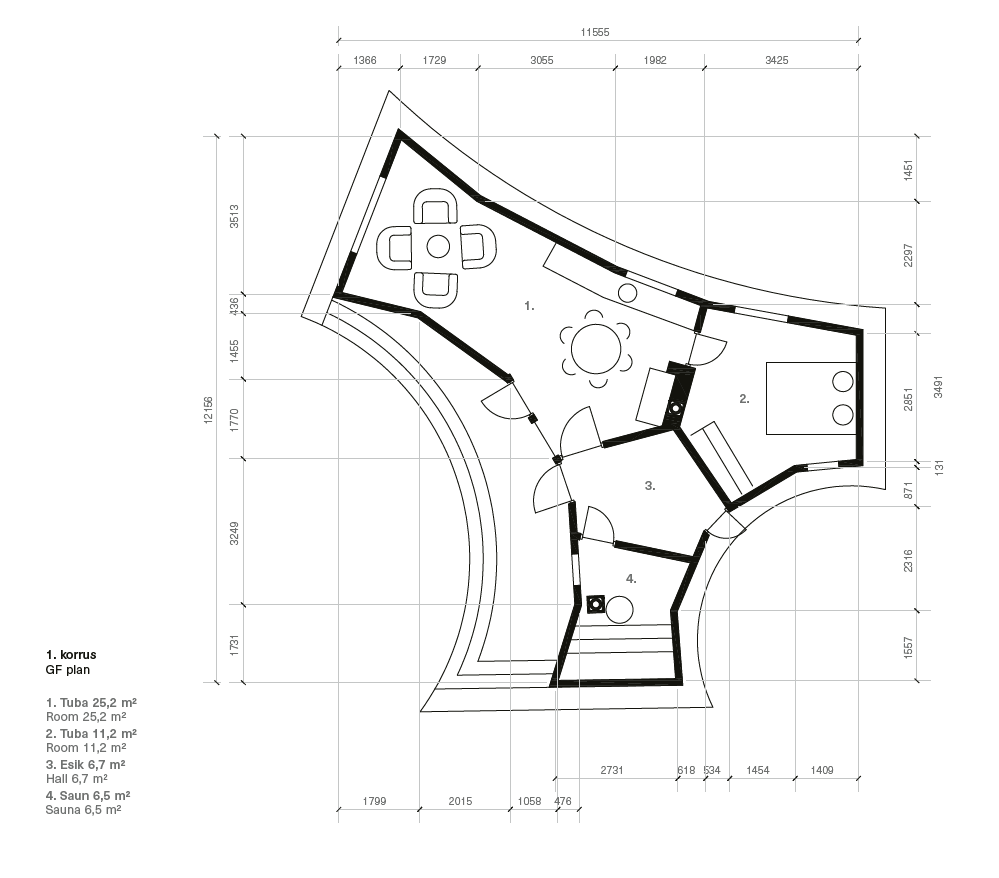

On the island, there is often strong wind from the sea. This is likewise so at the plot in Rannaküla. Wind and blocking the wind indeed became the main influences on the design of the building. On the eastern and western sides of the building, I designed small rounded yards that function as windsocks, creating calm, windless spaces there. And so it really is—the rounded yards do block the wind. The shape of the roof, however, was determined by the municipal design specifications that foresaw a pitched roof with a 35–45-degree angle. Thus, the building was shaped by wind and design specifications.

Wooden slat wall

What would be a reasonable size for the slats that are to be stacked in a wooden monolith? I decided to ask glulam experts. It turned out that anything beyond 5 cm will tear itself apart—i.e., become crooked and cracked—because the tree rings have not been sawn through. Hence I used 145 x 45 mm slats. How to bind them together? My idea was to glue them. However, the special two-component glue that is used industrially dries so rapidly that it is of no use on a construction site. The optimal choice turned out to be a simple P3-glue, which is nothing but the most common PVA glue that has been made water-resistant. This could be bought from the nearby hardware store in Orissaare in large buckets. When I went to the hardware store already for the third week to get several more buckets of glue, the shopkeeper asked me: ‘What are you glueing?’, and I said, ’I am glueing a house together’. The shopkeeper opined that in this case, they should order more glue: ’Well, go ahead then’. To prevent the layers from sliding apart while glueing and to apply some pressure to the slats, they were nailed together from the top. The nails remain hidden between the slats, so they do not affect the external appearance of the building.

Self-build

There was no electricity on the Muhu plot at the time, and since there had been no earlier precedent of building by glueing together a stack of slats, it was not possible to entrust the task to construction workers. Given that there was no electricity, the cuts had to be made with a chainsaw instead of a circular saw, and nails had to be used instead of screws. Yet, there was a set of rules for how to stack up the slats, and this provided a clear advantage—there was no need for measurements and blueprints; instead, the house could be built by following guidelines. Every subsequent layer of material is based on the previous one and verticality can be checked by simply using a spirit level. Building without measurements and blueprints is a privilege that you cannot afford every day. Building by a set of rules can provide you with very simple solutions—compared to projections and blueprints, a rule can simplify the building process. Take the example of a pyramid in Giza—to build it, it suffices to keep in mind the fractional number 9/10, for this expresses the geometry and metrics of the whole building. If you want to build a pyramid with the right proportions in your backyard, you need to take a piece of string that can be divided into tenths, use it to draw a circle on the ground, and set up two perpendicular lines within it to form a cross. Then you need to take a stick, which is nine tenths of the cross’s arm in length, and put it up. To get it vertical, you can attach strings on the top as struts and join the other ends with the ends of cross’s arms. And voilà—you have built the perimeter of a pyramid with perfect geometry by using strings. Simply pile it full of stones and you have yourself a stone pyramid. There is no need to mark the side lengths, face angles or any other measures. All you need is the fraction 9/10, which expresses the whole geometry of the pyramid. By reducing building to a set of rules, measurements become irrelevant to achieving a certain geometry, since rules and proportions will be sufficient.

Building as a prayer

In case of a building like my Muhu hut, it was possible to finish 1.5 layers in a day when working alone and 3 layers when working with helpers. Thus, the house rose by 7–13.5 cm in a day. There are altogether about 110 layers of wood in the central part of the building. As I repeated the same movements every day, raising the house became a form of meditation. Adding the layers of wood was like repeating a certain text over and over again, which begins to reveal new aspects and generate variations. Stacking up the wooden walls took about 60 days, weekends included, in the course of which 36 m3 of timber was stacked up. I approached the process as if I was creating a 1:1 scale mock-up. The resulting wooden monolith formed the main body of the house, which was later supplemented with a floor, roofing, windows, etc.

Eaves

When I began to design the house, I feared that the walls will become cracked, and that the morning sun will be shining into the room already at 6 o’clock from the resulting 10,000 slits, sneering at all my efforts. I was advised to consult Ago Kuddu, a true luminary of wood engineering and constructor of Linnahall in Tallinn, on whether stacking up timber in such a way is a reasonable plan at all. I braced myself and called the old master. It took about five minutes of muddled monologue on the phone to explain my plan. I had a gut feeling that I am wasting the grand old man’s time with some complete hogwash. However, the result was unexpected. After a confusing treatise about wooden slat walls, mr. Kuddu said: ‘If the plan is to build a wooden facade that could result in horizontal shelves for water and snow, and there is the danger that ice will begin to damage the wall, then equip the house with wide eaves. This will expiate everything’. I did as I was told, and indeed, there have been no technical problems with the building, except in one corner that extends out from under the eaves. This sums up all that I have learned about wooden architecture so far—a wooden building needs to have eaves.

A house without structural frame

If a building lacks bones—i.e., a load-bearing frame within the insulation—then the space is free in its form, because the structural part that separates off the interior of the building is both insulating and load-bearing. The whole wall is in one piece—there is no exterior and interior finishing. Given the requirements for airtightness and insulation of the interior that are in place today, adding layered materials has become almost inevitable, and this makes flat surfaces and 90-degree angles significantly more competitive than organic forms, which are nearly impossible to build economically in layers.

Thermal insulation of a monolithic wooden wall

The efficiency of a wall’s insulation is expressed by its thermal transmittance or U-value. With wood, this value is two times worse than with mineral wools—i.e., 15 cm thick wooden wall should be as cold as a merely 7.5 cm thick wool-insulated one. And yet, interestingly, in a solid wood building, it does not feel that way. How come? One possible answer is offered by Panu Kaila in his book Talotohtori [The House Doctor]. When you are boiling water, it takes quite a lot of energy to bring the water to boil and for the vaporisation to begin. The inverse of this process is condensation. Condensation—i.e., water vapour turning into liquid water—releases the same amount of energy that it takes to vaporise water in boiling. Panu Kaila hypothesises that solid wood walls are a kind of microscopic heating plant—near the dew point within the wall, water is constantly condensing, residual heat is being released, and at the same time, the capillary structure of wood drives that moisture immediately away from that zone, meaning that condensation can go on and on. This also means that the air in the room will not be excessively dry, for capillary humidity makes its way through the wood to the room, while the condensation-based ‘heating device’ within the wall is working. The colder the weather, the more intensively it works. Whether it is so or in some other way, I cannot tell, but a solid wood building indeed has excellent indoor climate and much better thermal insulation than you might expect based solely on its U-value.

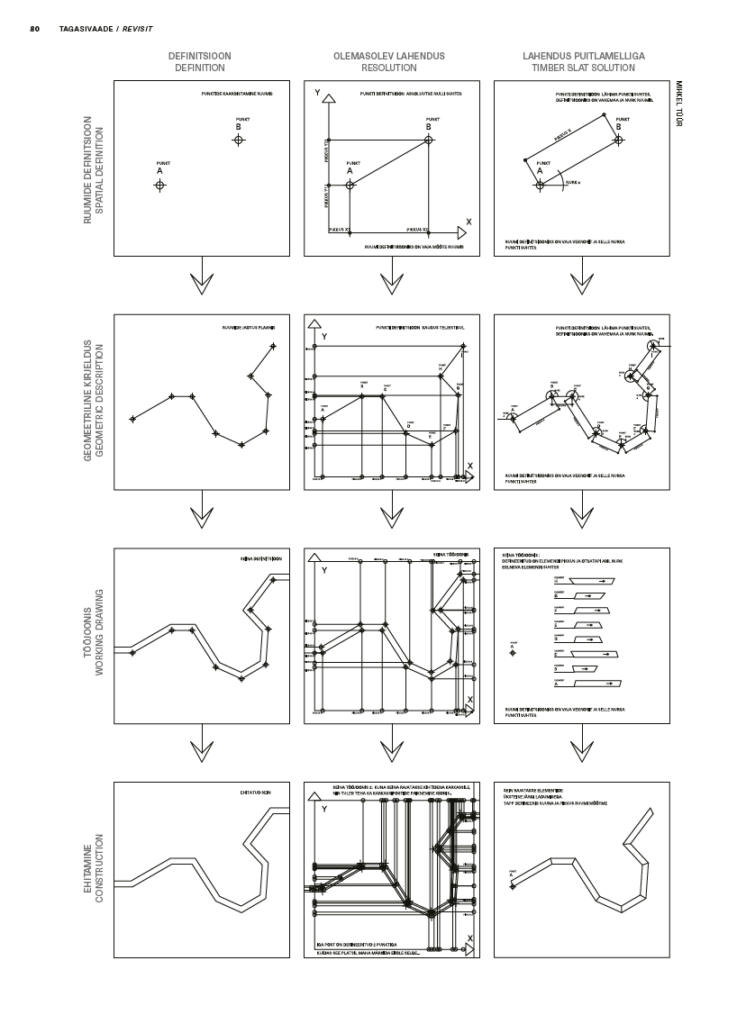

Wooden slat monolith as a construction system

In 2011, two years after the Muhu hut was completed, it occurred to me that this building method could be automatised and adopted as a construction system. The idea of using wooden slat monoliths in construction inspired contractor Mait Schmidt, together with whom we began to further develop the system. The development was financially supported by Enterprise Estonia, Peetri Puit, Raitwood Kapital and Lemeks. This led to a two years-long collaboration, in the course of which we tried to create a standard for such a construction system. For this purpose, architect Raul Kalvo wrote a Rhino script that divided a building volume automatically into slat-thick layers, each layer into sections, calculated the corner data for both ends of a section, and then presented the information in the form of an Excel table. In collaboration with Hundegger sawmill, this informational output was adapted so that it could be fed directly into sawmill machinery, which would then produce ready-cut building pieces that can be assembled by hand. We jokingly called it a low-tech 3D printer. In collaboration with the engineering department of the Tallinn University of Technology, foundations for the static load calculation of such structures were developed. Two 2 x 2 x 2 m test buildings stood in the university’s yard, on which settlement, moisture regime, airtightness and thermal insulation of the walls were measured. We designed a sample building (8-metre diameter spherical residential house) whose slat structure was calculated by construction engineer Otto Pukk. Unfortunately, in post-recession conditions, we were not able to create a fully developed standard for the system, for this is a long, costly and energy-intensive process within the EU legal space. Since we did not reach a sellable product, which could fund all that inventing, we were not able to bring the system to widespread adoption. However, the process itself was instructive and can be of use in case of other similar initiatives.

15-years-old architecture

My Muhu hut is 15 years old by now. This is precisely the interval after which a building is no longer contemporary, but neither is it yet retro. It is simply a non-contemporary worn-out space. I myself find it very enticing, because this is the timeframe in which only those qualities of the building remain that do not make a claim for something special; what remains is first and foremost a simple spatial experience. The wooden slat system has been subsequently tried elsewhere—for example, in patching up old log houses. One wooden slat house was erected with communal work near Otepää by Olympic medalist Erki Nool, who was extremely satisfied with the result. To me, the main charm of a single-layer wooden slat house is its geometric freedom, which is considerably more expensive and difficult to achieve with other construction systems.

MIHKEL TÜÜR has been working as an architect for about 22 years. He is still convinced that space is equally open to all and everyone can take part in shaping it. An architect has no upper hand here.

HEADER photo: Mihkel Tüür

PUBLISHED: Maja 114 (autumn 2023) with main topic ISLANDS