As a country that has experienced Europe’s biggest increase in real estate prices, we will soon face the question: how to avoid reaching the top in segregation and spatial inequality too? Hannes Aava explores.

In the age of the Roman Empire, many Romans lived in hazardous apartment buildings known as insulae and owned by the aristocrats. As two apartment buildings belonging to the esteemed orator and senator Cicero collapsed within a short interval due to poor construction quality, Cicero expressed no regret nor guilt over the suffering of his tenants in his letters to his friend Atticus. Instead, he had already come up with a good idea for earning an even greater fortune with replacement buildings.1

Although two thousand years later, social apathy and self-interest have not disappeared from this world, we can nonetheless acknowledge that regardless of the occasional collapses of apartment buildings and gas explosions, people’s living conditions in most of the world have significantly improved since Cicero’s lifetime thanks to the development of civil society. Increasingly, we can speak of a solidarity sanctioned by the public sector—for instance, even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN in 1948, established housing as a basic right, and today there are many cities and states that are actively involved in ‘corrupting the market’, i.e. steering the housing policy by curbing the real estate market order to keep cities socially diverse, lively, and affordable for as many sections of society as possible. This kind of policy is not only carried by social idealism but is also increasingly justifiable by the arguments of rational capitalism. When comparing the statistics on wealth distribution in various countries with the general competitiveness of these societies, we can clearly see that in Europe the countries with the lowest wealth inequality (e.g., the Nordic countries and Slovenia) are also among the most competitive ones. Solidarity literally pays off. In almost all of these countries amongst the inequality reduction mechanisms are, namely, the housing programmes.

The roots of affordable housing programmes extend back to the 19th century workers’ districts. However, the strategic state programmes developed mainly in the 20th century over the course of which their popularity fluctuated constantly due to some major failures and shifting ideological tides. In Western and Northern Europe where owning real estate is much less common than in Eastern Europe, each country has developed its own version of a state programme by now, and there are signs that the goals set in Estonian spatial strategies are similarly unlikely to be reached without the public sector’s intervention.

Estonia—a future European front-runner in inequality?

The 82% home ownership rate of Estonia is among the highest in Europe and would have probably earned praise from Margaret Thatcher, a fierce opponent of state intervention and state housing programmes. Granted, there are some merits to such a system—being a homeowner increases one’s sense of responsibility towards the property, offers a certain kind of psychological security given our nation’s historical traumas, alleviates the traditional right-wing fear that the state is turning into a so-called nanny, etc. Certain social strata are also pleased with the growth of real estate prices in Estonia which has been record-shattering in the context of the EU—since 2010, the prices have increased by 213%. This increase significantly exceeds the wealth growth of average Estonians in the same time period, which was on average 50% in 2013–2020.2 There are no indications that this process is stopping—real estate prices have continued to rise in spite of massive inflation and a cooling economy.

Given this record increase, one of the central questions of socio-spatial cohesion is, how many members of the society are able to participate in this kind of price hike? Where is all the earned money spatially concentrated in? Mark Aleksander Fischer, in his master’s thesis titled ‘Planning Affordable Housing in Põhja-Tallinn. Kopli Freight Station—the Last Piece of the Puzzle in the Socio-Economic Landscape of Northern Tallinn’, which was defended in the Estonian Academy of Arts in 2023, calculated the affordability of apartments for sale and for rent in relation to the median salary in Harju County. The resulting picture is not much of a surprise to anyone who keeps up with the prices of new properties entering the market. According to Fischer’s calculations, there are no longer any districts in Tallinn where the purchase prices of new apartments would be affordable to someone earning the median salary in Harju County, and even the rents are affordable only in Lasnamäe and Pirita.

At the same time, the population of Tallinn still shows a growing trend, and the more optimistic forecasts predict that it will grow to 552,000 inhabitants by 2050.3 Why, then, does the rise in prices pose a problem in the context of spatial issues? Recently, there have been increasingly many discussions about the segregation of the urban population, which also happens to follow strong ethnic and age-related parameters.4 The rising cost of living and poor quality of urban space, including its green areas, are among the root causes of urban sprawl and segregation. This leads to socio-economically homogeneous and inequality-amplifying districts, and to the weakening of general social cohesion, which in turn creates a fertile ground for alienation of different social groups and the resulting political polarisation. In the Estonian context, it certainly does not help with integrating those who are hostile or indifferent towards the state, or socially ostracised. If things continue to develop in this direction, it is difficult to see how the city of Tallinn or Estonia as a whole could fulfil the goals set in their strategies that prescribe more reasonable land use, reduction of emissions in the construction and transport sectors, improvement of mobility, urban densification, a more cohesive society, etc. If no changes are introduced, there is the danger that the same car-centric urban sprawl and spatial-economic stratification that has accompanied our spatial developments over the last decades will continue to grow inertly.

Housing policy—for whom and how?

Still, it can’t be said that nothing has been done—after all, several cities have their own social housing programmes, and Tallinn also has a municipal housing programme with 1822 apartments. Yet, conceptually, in the wider socio-spatial context of the city, one can note a lack of social diversity—social and municipal housing is generally kept emphatically separate in the urban space, and is usually situated in lower-income districts. These places tend to lack high-quality infrastructure and comprehensive urban environments that would render the districts attractive for wealthier residents. Furthermore, social and municipal housing units, even more so than the regular new property developments, seem to suffer from the architectural problem with the typology of apartments—the buildings lack spatial flexibility that would enable to adapt the spaces according to changes in the lives of the residents, such as residents having children, or their children growing up and moving out. Examples like the complex in Raadiku, which began to be built in 2008 and today has 4000 residents, and the recently failed affordable rental building in Otepää, where the town was forced to simply sell rather than rent the apartments due to rising prices, have painfully demonstrated by now that, just like with building 2+2 roads, developing enormous volumes of car infrastructure and gigantic shopping malls, and other dubious spatial planning decisions, we still lack the skill to learn from the mistakes that were made elsewhere decades ago.5

In the late 20th century, housing programmes organised by the state became associated with grand failures that turned into symbols for the decline of the whole modernist paradigm. Many cities, especially in the United States, threw out the baby with the bathwater and opened the door to a housing policy that led to extreme urban sprawl and the accompanying extensive motorisation, growth of inequality, loss of communities and increased homelessness in many cities. Although experiments with affordable housing projects were not conclusively dropped, so far there have been few successes in the United States that could be compared to Europe. However, as we look for examples for Estonia to follow, it is important to emphasise that the greatest failures of affordable housing and social diversity programmes in the United States have almost invariably happened when the private sector has been given too much influence over rejunevating a neighbourhood—this always leads to accelerated gentrification and displacement of the socially underprivileged.

Elsewhere, however, traumas have been overcome, and it has been understood that the problem with affordable housing policy does not lie in ideology, but rather in inadequate methodology. Social housing and heavy intervention by the public sector in the real estate market is sexy again in countries such as France, the Netherlands and Denmark. Examples of successes with this approach include Paris and Vienna, which are also among the places with the highest quality of life in the world. In Vienna, for instance, approximately 60% of the population is today living in publicly subsidised housing, and the city is vigorously acquiring land and favouring the involvement of non-profit organisations in developing social housing (as well as comprehensive high-quality urban space and infrastructure), all the while observing that the public intervention would not excessively damage the interests of private real estate developers.

It is increasingly important to involve the future residents already in the planning stage. There are systematic attempts to make the social cocktail within a block as well as the whole area as diverse as possible. Run-down districts are eagerly renewed, ensuring that the quality of social housing does not fall short of average market levels, thus preventing the area from falling behind. One effective method here is civic society-based development, which can offer the residents impressive benefits and spatial quality. Implementing it in Estonia where this sort of civic tradition is lacking would imply either major social changes or artificial attempts to create civic associations with the appropriate competences.

Equally impressive is the housing programme in Paris, which is organised by the non-profit sector and connects affordable housing with climate goals, use of local building materials, reduction of mining of construction minerals, re-use of old buildings, and other important objectives. The programme of the largest provider, the non-profit giant Paris Habitat, pursues a sensitive pricing policy and offers housing to every ninth Parisian, including people earning slightly below the median salary as well as those earning much below average. An important aspect is its pursuit for architectural quality, which is evidenced by the 2021 Pritzker Architecture Prize for Anne Lacaton’s and Jean-Philippe Vassal’s contribution to the programme, and experiments with sustainable construction policy and materials like hempcrete.

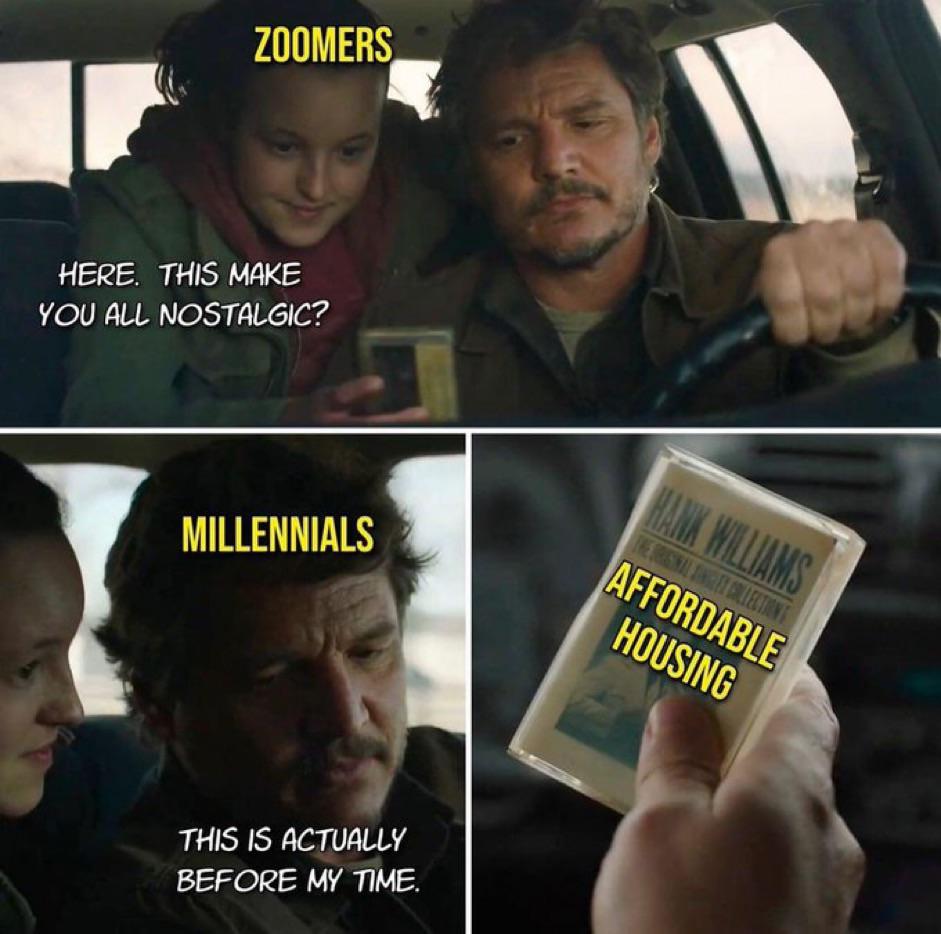

Source: Affordable Housing, digital image, Reddit, 20.07.2023

Community vs developer

In the Estonian setting the format of citizen-formed housing construction cooperatives might be suitable, although this would involve rather the economically more secure and proactive part of the society, who are generally not the first to be pushed out of cities by price pressures. I nevertheless agree with Fischer that supporting housing construction cooperatives is something that should be considered, and that it could take place in the framework of a possible KredEx measure, which might be suited for young families as an affordable housing start-up grant, and enable them to be actively involved in creating their future dwellings. One important prerequisite for this is abandoning the parking space requirements of Estonian municipalities.

Lately there have been signs that the city of Tallinn will look for a partner (presumably from the private sector) who would develop the area around Linnahall, and to whom the land will be sold. In light of this, we should take note of the community land trust system that is increasingly popular in Europe and North America. With such a system, the local authority does not aim to sell the land for a quick cash injection in order to patch up their budget holes, but rather leases it to a non-profit civic association that has been formed to develop housing there, thus enabling the future residents to actively participate in the process of designing the dwellings, and to receive a home that is appropriate to their standard of living.

Given that Tallinn is governed by two parties for whom social equality has been an important issue, trying out one of the described methods might offer a more sustainable perspective than selling the land to some private actor who is most likely to build another segregating project with elite-oriented business properties and exclusive apartments. Karen Barke, who is involved in renewing the property of the city of London and developing its social housing, gave a nice summary of the shortsightedness of this course of action: ‘Parcelling off bits of land and selling them to the highest bidder is not an approach that creates viable, long-term affordable housing for London, and it does not provide the financial security needed to deliver vital local services. Eventually, the land will run out and so will the short-term income stream from sales that come with it.’6 Not to mention the fact that the city loses another control lever for steering its development.

Left turn allowed at the intersection

It seems that we are currently standing at a decisive crossroads. In one direction, there is the decision to establish the conditions for a strategically organised public sector policy that would aim for social security, social cohesion and intensive, socially as well as functionally diverse spatial planning. In the other, the continuation of the current free market-based development, where the public sector keeps lagging behind the events, urban districts become more and more socially and economically segregated, and places like Tallinn city centre and Põhja-Tallinn become enclaves with economically homogenous populations. Many earners of lower incomes will be pushed to more slowly developing apartment block districts or cheap new housing districts built on the fields in nearby municipalities, where their lives will be spent on making home loan and car leasing payments so that they could commute to the city for work, culture and social life.

Some rays of hope here and there suggest that we are taking the first steps in the former direction. In Tallinn and Tartu, the apartment block districts that accommodate a large part of the population have been receiving more and more attention—e.g., in the form of improvements to the quality of buildings, public spaces and green areas. Numerous Master theses defended in the universities confirm a growing interest of young architects and planners in social and empathetic projects. They appear to be casting aside the tepidity towards social solidarity which characterised much of the previous generation.

As part of the coalition agreement of the current government of Estonia, spatial planning will be centred in the Land and Spatial Development Agency (Estonian: Maa- ja Ruumiamet, abb. MaRu), set to be launched in 2025. Although the agreement also includes a pledge to reduce inequality, looming housing cost crisis and spatial segregation are not mentioned in the 2018 final report of the MaRu expert group. This, however, might be because the problem has become much more salient in public debates than it was in 2018. Here it is pertinent to recall the project New European Bauhaus, which was launched by the European Commission and will be implementing the green transition in the domain of spatial issues. Three main themes in its statute are sustainability, beauty and inclusion, where the latter is explicated in terms of diversity, accessibility and affordability as central goals.

To conclude, I shall return to the beginning. The example of Roman insulae was in reality more ambivalent than simply a piece of evidence for lack of human solidarity. The ground floors of insulae were often occupied by small resident-managed shops that interacted with the surrounding street life. It seems that already the Romans understood intuitively the benefits of multifunctional buildings, density, and lively street frontage—the virtues of which have been convincingly recounted by urbanists such as Jane Jacobs.7 Such principles, together with social diversity, could be our guiding parameters when designing our future affordable housing programmes.

HANNES AAVA leads the Green Tracks Project at Tallinn Strategic Management Office’s Spatial Design Competence Centre. He studies landscape architecture at the University of Greenwich and from time to time writes about (urban) spaces.

HEADER photo: Erik Holm

PUBLISHED: Maja 113 (summer 2023), with main topic Housing

1 Harvey, Laura. ‘Dangers of Living in an insula.’ Rome: A City of Rental Property (course project).

2 ‘Uuring: keskmine eestlane on saanud kõvasti rikkamaks, aga ebavõrdsus on tohutu.’ Postimees, May 26, 2023.

3 Aivar Jarne. ‘Sotsiaalteadlane Mare Ainsaar: Enim hakkab kasvama kesklinn. Popimad elukohad on kesklinna kõrval veel Haabersti ja Pirita.’ Pealinn, May 3, 2023.

4 Riina Aljas, Oliver Kund and Mari Mets. ‘Tallinna nähtamatud müürid,’ Levila, March 2022.

5 Mets, Mari. ‘Tallinna suur prohmakas nimega Raadiku: sotsiaalkorterite kommuun on kasvulavaks sadadele hädas lastele.’ Eesti Ekspress, April 3, 2022.

6 Karakusevic, Paul, and Abigail Bachelor, Social Housing. Definitions & Design Exemplars. RIBA Publishing, 2017.

7 Jacobs, Jane. The Life and Death of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.