GOLDSMITH STREET

Type: Social housing

Architect: Mikhail Riches, Cathy Hawley

Landscape architect: BBUK

Passivhaus consultant: Warm Low Energy Building Practice

Structural engineer: Rossi Long

M&E: Greengauge Building Energy Consultants

Density: 83 dwellings/ha

GIA: 8058 m2

Client: Norwich City Council

Contractor: RG Carter

Construction cost: 1875 £/m2

Passive houses have a thick airtight skin and small eyes, they are certified based on inflexible standards, and at their core is a machine with a demanding maintenance regime. Nevertheless, in the United Kingdom, a number of councils have adopted the passive house method in order to realise their growing ambitions in the housing sector. Could this also lead to an increase in spatial quality?

In the 1980s, ambitious council housing programmes in the UK were scrapped, having been strangled mainly by Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal iron grip. Since then, the winds of austerity have been blowing rubbish around in the courtyards of apartment buildings, while their composite panel façades have come to reflect the current relationship between the free-market economy and architecture. Due to deteriorating housing affordability and housing stock, and rising energy prices, it is increasingly critical that councils intervene more ambitiously in the housing sector.

In November, I visited a social housing neighbourhood on Goldsmith Street in Norwich, a town near the eastern coast of England roughly the size of Tartu in Estonia. In 2019, this neighbourhood became the first social housing project as well as the first passive house project to win the most important annual architecture award in the UK—the Stirling Prize. When the architecture practice Mikhail Riches won the architecture competition for this neighbourhood more than ten years ago, the council could not find a suitable partner from the private sector to develop it. Ten years later, the council took over the development and imposed an additional condition on the architects—the buildings must be certified as passive houses.

Photo: Tim Crocker

A passive house is, in principle, an airtight house. Its walls are thick, with every bit of air gap carefully taped shut. And this is not something that happens only on paper—during the construction process, including in its final stage, the buildings are put through an air pressure test that checks on this aspect. A passive house is required to have a heat recovery ventilation system, which should ideally be its only heating element. Before reaching the interiors, air passes through a heat pump and its filters, meaning that it arrives in the rooms cleaned and conditioned. Passive houses have significant similarities with the nearly-zero energy buildings specified in the EU requirements, but unlike the latter, the passive house status comes with certifying the completed building. They also have stricter requirements regarding the shape of the building (form factor), the size and number of windows, and the use of passive heating solutions.

Are passive houses an example of the ecologisation of architecture or technology? Or is it instead pure economisation? The municipalities in the UK that design their social housing as passive houses put much emphasis on the low heating costs that come from airtight walls and efficient technology. In this way, they can protect the interests of their low-income tenants while also ensuring that the council budget does not suffer rent voids. Fuel poverty is a serious problem in the UK. Municipalities also tend to like the fact that ‘passive house’ is not simply some abstract term. It stands for a set of guidelines and techniques, a domain of independent accredited experts, and is thus perfectly suited to today’s world where consultants proliferate.

Passive house means that the actual completed building is tested by designated experts, meaning that the quality of the building is under increased scrutiny. Ultimately, passive house means that the building has a certificate, a stamp on a diploma, and a plaque on the exterior wall saying, ‘Certified Passivhaus’. A house either is or isn’t a ‘passivhaus’—there is no arguing or debating over it.

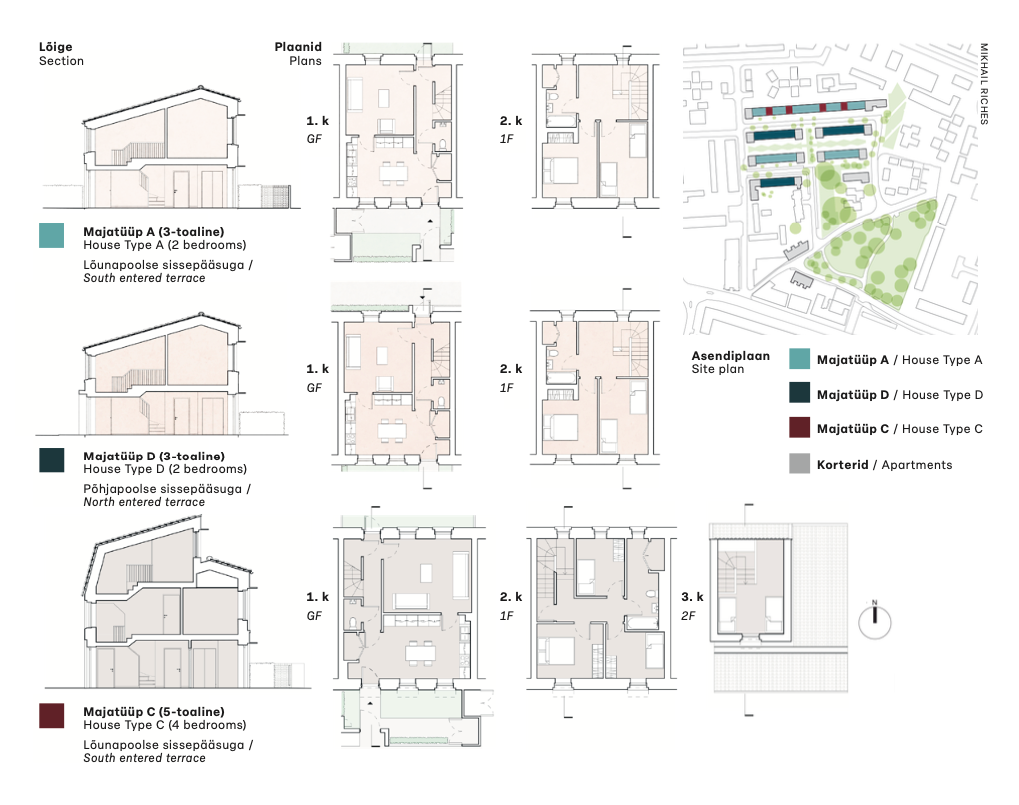

The Norwich project has 105 homes, some of which are apartments, while most are two-storey houses. Each and every one was social housing on completion. The building volumes take into account the possibilities of solar heating. The building materials have been selected so as to make use of thermal mass. The project plan reveals that the buildings are built on wooden structures and mostly insulated with cellulose wool. Yet, the windows are smaller than the architects would have liked—this, too, is obvious from looking at the façade and marks the materialisation of the greatest passive house-related fear architects tend to have, i.e., limited window area.

Photos: Laura Linsi

While I was taking photos of the neighbourhood on Goldsmith Street, I was approached by a dog walker. She pointed to a rounded corner of one of the buildings and noted, ‘A-ha, forms and curves… Are you a photographer?’ And I responded that, well, no, I am actually an architect, and those buildings are interesting to me due to this being one of the largest passive house neighbourhoods in the UK, one that has been developed by the council to boot. Upon leaving, the walker said that she often goes to fetch a dog from one of these houses, but did not even know that the buildings are somehow special, and added that from now on, she will be seeing them in a completely different light.

Then again, what is the point of looking at them from a different, passive-house perspective? Instead, we should notice how nicely the streets of the new quarter have been connected to the existing ones and that every home has its own front door opening to the street, which makes for safe urban density. Or also the fact that the older and newer buildings form a unified whole and thus a coherent place to live at. Or that this here is indeed a new development with low rents, small energy costs, cosy street space, and homes with a healthy indoor climate. Such seemingly simple, but essentially long-term solutions are one way in which local governments can be agents of change and quality.

LAURA LINSI is an architect at LLRRLLRR, a lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts and the University of the Arts London, and the editor-in-chief of MAJA.

HEADER photo by Laura Linsi

PUBLISHED: MAJA 4-2024 (118) with main topic AIR

1 ´Grenfell Tower: What happened´, BBC, 29 October 2019

2 The ecologisation of technology and architecture is the focus of the discussion between Roland Reemaa and Eva Gusel in this issue (118).