A thoughtfully prepared comprehensive plan acts as a basis for spatial planning decisions, but it is not a substitute for on-site expertise – each local government needs a planning specialist.

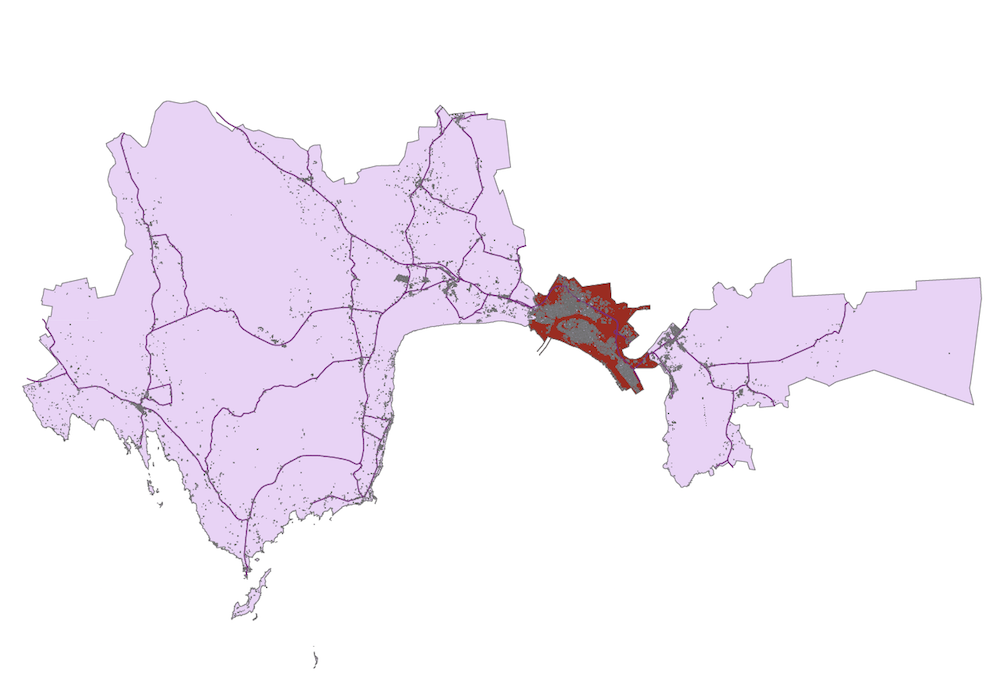

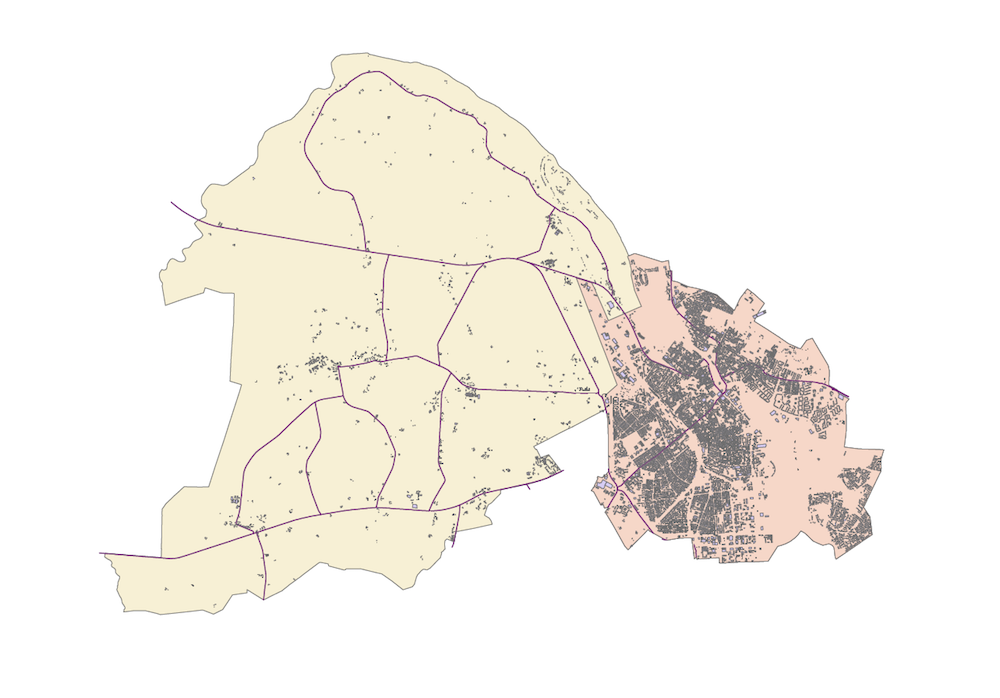

The local governments that were formed after the administrative reform are larger and, above all, more diverse. They combine cities and rural areas, communities of different nationalities and cultural backgrounds and entire counties. Expectations are high – the state hopes that these new administrative units will be stronger partners than previous smaller units, while residents expect improvements in their quality of life.

What are the spatial features and qualities of the new local governments?

The legislative body has demanded that the combined local governments establish new comprehensive plans within three years. This is how long the preparation of such a plan usually takes. However, more time may be needed in the case of the new administrative arrangements. A comprehensive plan presents an opportunity to establish sensible rules for managing development, spatial organisation and design. A rushed plan or, worse, spatial development directions and requirements that are automatically adopted from a former local government make life more complicated.

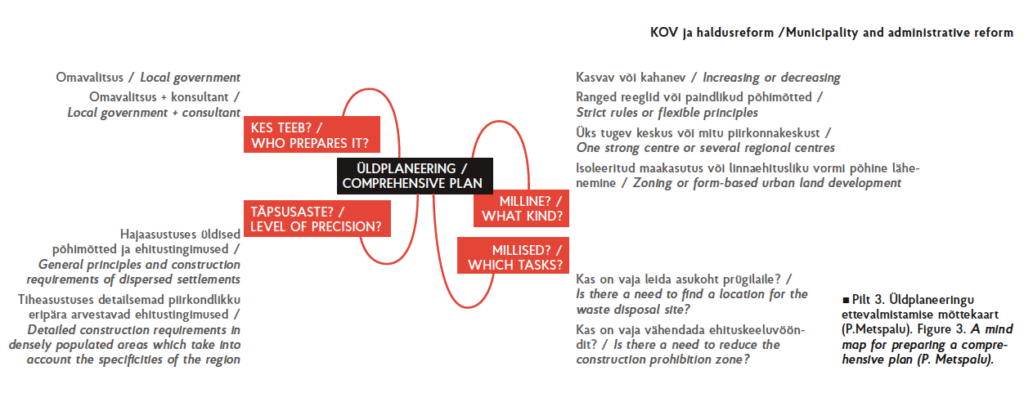

Preparation of a comprehensive plan also requires prior planning so that it actually works as a spatial development tool once it is completed. It is unwise to rush into initiating a comprehensive plan and a public procurement to find a consultant. Instead, it is better to establish the spatial features of the new local government first and to think about what problems the comprehensive plan should solve (and how) and to determine what kind of experts are needed to prepare the plan. Consultants can help to organise ideas where needed1, but the substantive work regarding the specification of the objective and tasks of the plan can only be done by the new local governments.

The tasks that are to be solved by a comprehensive plan and the method used depend on the needs of the specific local government. It is easy to interpret the new Planning Act adopted in 2015 in a way that suggests that new comprehensive plans should be all-inclusive preparatory documents for construction work in the near future, resembling a detailed plan. A more accurate approach that focuses on height and density is entirely justified when it comes to built-up urban areas of cultural and environmental value, but high-precision construction requirements are rarely needed in the case of rural areas. The different nature of urban and rural areas must be considered when creating a comprehensive plan, especially in the case of new local governments with large territories where former neighbouring municipalities have been merged with the city, e.g. Pärnu, Haapsalu, Paide, Tartu and Narva-Jõesuu.

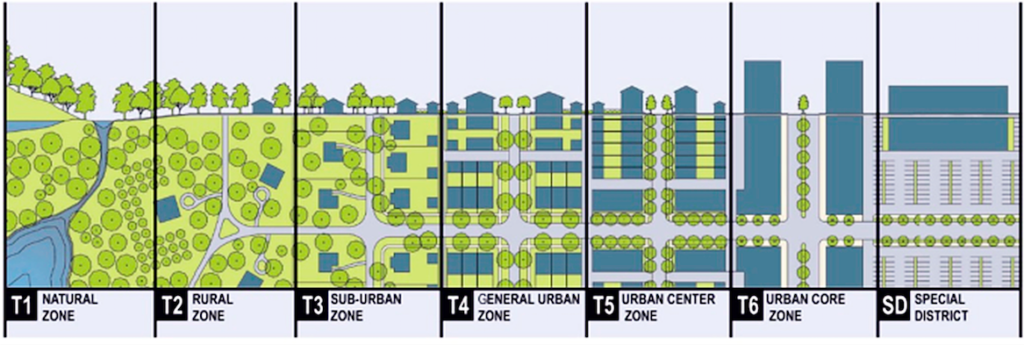

Focusing on the establishment of precise construction requirements for the entire local government is a slippery slope that quickly turns comprehensive planning into a troubling obstacle for the design process, which should be bypassed. A comprehensive plan is essentially a strategic, long-term, forward-looking document that provides a basis for all kinds of decisions that are linked to space or that have a spatial influence. It makes sense to remain open to possibilities whilst maintaining values. Values should be based on the most important asset of each local government – its people – and solutions should be discussed with village elders and communities. Comprehensive planning of cities and the surrounding rural municipalities that have been merged with them means constant deliberation regarding a suitable precision level: one that would combine long-term flexibility with a sufficiently specific basis for everyday detailed planning and design. One solution is to use the so-called form-based code popular in the US, which is based on the density of the constructed environment and differentiates between high- and low-density areas.

The aim of this planning method is to establish requirements for creating a human-friendly space that facilitates different ways of moving based on the intensity of the use of space and housing density.

Planning must be based on needs

Central rules, which tend to become laws and regulations in law-abiding Estonia, may not correspond to local specificities and requirements and often express spatial blindness, i.e. they cannot foresee the consequences that occur in real spaces. The new Planning Act supports, intentionally or otherwise, local governments – subsection 75 (2) clearly states that decisions on the tasks to be resolved by the comprehensive plan prepared in respect of the territory of several rural municipalities or cities should be based, among other things, on the spatial needs formulated in the development strategy of the county and on the purpose of the plan. This gives local governments the full right, but also the obligation, to decide which tasks to resolve with their comprehensive plans and on the level of detail.

Development of a comprehensive planning solution requires perception of space on different scales. Global societal development trends such as increasing mobility and aging populations require positioning of local governments in Europe, Estonia and counties. These trends manifest themselves in the local spatial language of cities or rural municipalities, which reflect the construction traditions and lifestyles characteristic of these places. This spatial language is above all spoken by the residents of these areas, i.e. local government officials/specialists. In order to identify with development trends, assess the influence of different solutions and navigate through legal space, it is useful to include consultants. However, substantial work will in any case remain the responsibility of local governments. Consultants who are more experienced in planning can help in interpreting spatial development directions at the state level – e.g. what the term ‘sparse city space’ mentioned in the National Spatial Plan Estonia 2030+ could mean in, for instance, peripheral rural municipalities and how to address the urban settlement areas specified in county plans. County-wide spatial plans provide directions for creating comprehensive planning solutions that are based on the state’s needs but still correspond to the specificities of regions. Consultants should be able to offer solutions that support web-based analysis in order to make the planning process easier.

Unfortunately, there are rumours that representatives of several local governments feel that officials who deal with the daily management of spatial planning are no longer needed. The reason given for this is the fact that the new local governments are so large and complex that all plans will need to be outsourced in any event. However, the purpose of the administrative reform was to boost local competence. The understanding that the aim of planning is to map regulations trickling down from above and to set restrictions is unfortunately gaining ground.

Determining the content of and authorisation connected to spatial planning is currently high on the agenda of several countries, e.g. Finland and Norway. The necessity of local planning competence is generally not challenged upon reviewing the spatial planning system. On the contrary, Scottish local governments, for example, are planning to establish the position of a statutory chief planning officer. Above all, the chief planning officer is an adviser who uses their expertise to assist municipal councils in making decisions that concern spatial planning. Other responsible officials are obliged to involve the chief planning officer in preparing the decisions made in this field as early as possible.

Until recently, the Environmental Board played the most important role in the strategic assessment of the environmental impact of spatial plans, but now this responsibility and discretion lies entirely with local governments. Changes in the Environmental Impact Assessment and Environmental Management System Act establish that the Environmental Board will continue coordinating impact assessment reports, but it will no longer have the discretion to approve or reject them. Decisions on the sufficiency and use of the results of strategic assessments of environmental impact will hereafter be made by local governments. This in itself is natural, because planning is already the responsibility of local governments. At the same time, this change means that rural municipalities and cities must have an official whose competence is equal to that of an environmental specialist and is familiar with the world of spatial planning.

In larger local governments, the planning team should be formed not only for organising the preparation of plans, but also for the strategic guidance of development. Even if spatial plans are acquired from elsewhere, the party that places the order must understand the local government’s needs, how to fulfil them via planning and the effects of the plan once implemented. A strong local government must be able to manage its diverse space so that the benefits of the administrative reform are seen in real life.

PILLE METSPALU is a member of the management board of the Estonian Association of Spatial Planners and works for the spatial planning and environmental management consultancy firm Hendrikson & Ko OÜ.

Above: Vaksali square in Tartu, authors: Landscape architecture office Kino, Tartu City Goverment. Photo Erge Jõgela.

Published in Maja’s 2018 winter edition (No 92).

1 More information on planning procurements and the necessary preparations can be found in the new instructional material Soovitused ruumilise planeerimise hangete läbiviimiseks (‘Recommendations on conducting spatial planning procurements’) prepared by the Estonian Association of Spatial Planners with the help of the Ministry of Finance.