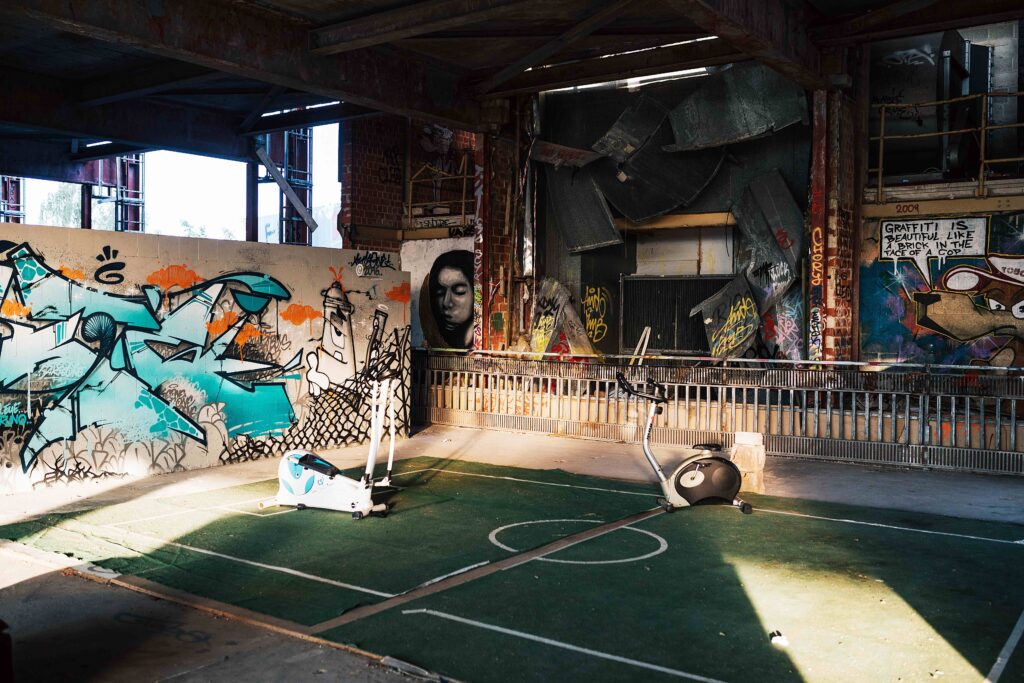

The capital of Germany is a maze of rules where imagination flourishes in the underwood. Although Berlin may come across as the capital of tolerance due to the various forms of diversity, it also has its controversies.

When I moved to Berlin last year in summer, I bought a bike by the end of my first week there. A bicycle is an obvious part of your body in this city. It’s not that the U-Bahn is not reliable, it is, but the capital of Germany is one of the places with a proliferating cycling culture. Why? The cycling lanes covering the city are not actually as comfortable as in Holland where the wide asphalt roads are separated from car traffic and line the entire city in their own right. The equivalents in Berlin are actually somewhat wimpish narrow lanes paved with stone rather than asphalt and in most cases sharing their right to exist with pedestrian paths. It is not uncommon that you need to bounce over tree roots protruding through the stones. Nevertheless, I continuously cycled in Berlin, even in winter. The traffic in Berlin flows kindly at a steady pace through the city with all vehicles reaching more or less the same speed when they wait up for the slower ones at the red light. My favourite activity was to cruise in empty streets at night listening to some old techno-mixtape. This was surpassed only by flowing with some friends along the street rivulets leading to an exhibition, park, café or party, when the journey became equal to the destination in terms of spending quality time.

I began to notice the reasons for taking specific trajectories. During the first months, the routes were so to speak public – to an exhibition, theatre or bookshop. Sometimes I went for a walk just to get out of the house and my feet took me to a shopping centre – stress relief had become a commercial trajectory. By late autumn and winter, I had got to know the people I had met better. I noted that my routes and their destinations had become entirely personal. I no longer went alone to public buildings or events such as exhibitions, theatre or bookshops (or if I did, then only to meet somebody). I took my bike from my personal space – home – to another personal space – my friend’s house – or from my friend’s place to a park to meet up with another friend. I sometimes tamed public spaces for them to become mine. For instance, I could go down the stairs out my house, cross the street and step into a gallery, hug my gallerist friend and dance together to Kendrick Lamar until we could close the gallery and leave to another personal spot. The abundance of private trajectories seemed to illustrate the network of relations that I had developed in Berlin – without the given relationships I would not have been walking down this road in that direction – I would not have access to that bar after closing time to gulp down colourful beers with the barista and talk about feelings.

Until in the following summer, it was time to leave Berlin and I had to connect the trajectories with one another, to tie them together. With two companions I staged a performance – actually there was no performance as a separate goal, it was rather a process among us. The three of us agreed on meeting points all over the city where we went by bike. The meeting points were kind of stations to accomplish a specific task. The trajectories covered Berlin as a network as every cyclist moved towards the destination alone to meet one person. One station was for fulfilling a task alone.

The first task was to leave home at 9 o’clock. As agreed, I put on a long cocktail dress in blue and red and sat on my bike to go to my previous neighbourhood in Friedenau with a vast maze of gardens behind my house. The given gardens are basically similar to the web of dachas in Eastern Europe but tidy and filled with garden gnomes as befitting Western Europe. The Germans grow fruit and vegetables there or merely mow the lawn in order to walk naked and read papers in their little cottage in summer. I was cycling in the maze in my dress and humming to myself some poems, “As soft as snow / are the lips of wolves”. The aim of the meeting was to read poetry to an agent. Some 40 minutes and several laps around the orchards and rose bushes later, we had found each other and read poetry (Kristiina Ehin, Wisława Szymborska, Tove Jansson) accompanied by a cup of thermos coffee, I took off my dress and gave it to her to wear. We went our separate ways, she to the Velodrom in Prenzlauer Berg to meet another agent to paint each other’s faces and dance, while I was going to Tempelhof to write my diary. As I reached Tempelhof, I first circled around the closed amusement park in scorching sunlight with children running from one colourful tent to another and then passed the refugee camp established in the main building of the airport.

The former military airfield Tempelhofer Feld is now merely an urban park with nothing but a few trees, a vegetable garden and giant hayfield with ravens flying above it. The length of the field is 1 kilometre with an empty expanse between and around the two runways. This is one of the favourite places among the locals to relax. It also used to be my favourite place to lie down on the grass and feel that the world included only me and the sky. The Tempelhof hayfield became the main place for me to relieve stress and gather my thoughts. Its location near my house was also great. As a part of my assignment, I lay down on my back on the grass, took off my clothes as it was one of the sultry dog days of summer and wrote into my diary, “Will we stay friends for long?”

Local people feel strongly about this empty field. In a city referendum in 2014, the residents were asked if they agreed to allow 4700 new flats to be built on the edge of the field. The majority opposed the project and the mayor was forced to scrap the plan and admit that Tempelhof will remain as it is. The citizens could thus show their conviction that an empty field in the city centre is important to them while the city government demonstrated that they accept the citizens’ decision.

The issue was raised once again this year and all hope is now on the protest culture of Berlin that could help to leave the area untouched also this time. The resistance is always present in the city streets. For instance, recently there was a march against racism, xenophobia and right-wing extremism near the Brandenburg Gate participated by over 200,000 people. Last summer, a brigade of lesbians marched through the streets to secede from the commercialised Gay Pride and express their independent lesbian pride. Similarly, there was a queer job fair in Neukölln attended by institutions directly related with the gay community and also companies merely expressing their support, while there was a small group of people in front of the convention centre protesting against the large corporations represented at the job fair.

I relied on my intuition to time my journey to the next station. That was the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park. The ride seemed long mostly because I felt my tires were melting into the asphalt. As I reached my destination, I was met, contrary to the disorderly expanse of Tempelhof, by a giant square with its architecture celebrating a totalitarian regime. At one end of the memorial, there are large steps down to a paved square leading along panels featuring Soviet soldiers and working-class families to the cylindrical staircase showing the way to the memorial of a Soviet soldier commemorating the liberation of Germany from the Nazi regime. Some people call it the Tomb of the Unknown Rapist to highlight the brutality of the Soviet forces.

As I was circling around the square under the shade of the trees, I discovered a fountain watering the lawn that I could pass under to cool off and ponder my post-Soviet feelings for the square. Until another agent arrived wearing a blue and red dress that the first agent had given her at the previous station. Our task was to take turns in answering the questions written on a piece of paper. Where do your bitternesses lie? How psychic are you?

No matter how wild Berlin may seem, the state is always present. The state kicks you out of the park at dark to lock the gates, the sate patrols your street if you and your neighbours are not white and the state daily sends you a new notice with a claim or a bureaucratic procedure.

After accomplishing my task and running through the secret fountain again, we went our separate ways to the next station where all three of us were supposed to meet. This was a flower shop in Sonnenallee that I had never visited before but had always wanted to step in. Sonnenallee is the artery of Neukölln with the dual carriageway studded with vegetable stalls, shisha bars, barber shops, falafel restaurants and phone stores. And about every twenty metres there must also be a scaffolding for façade renovation turning the pedestrian path into a particularly narrow cave passage. The air is thick with waterpipe smoke, kebab heat and gas emissions from the buses. And people are thronging past each other with strollers, wheelchairs, bikes, all going about their business.

The flower shop we entered was full of plants with thick green leaves, colourful blossoms, twigs and roots all thrusting up the walls towards the ceiling. In one of the corners, there was a textile pouf and a glass table for drinking coffee. Once all three of us had arrived, we took a seat – the shop was quiet, warm and peaceful in stark contrast to the general hotchpotch and noise in Sonnenallee – and stood up again without saying a word in order to go to the Lebanese falafel place across the street and continue our imaginary conversation. The discussion was to be carried on so that one puts a piece of imaginary information on the identity of others on the table, the next one will grasp at that and continue the topic. In the end, we were three researchers, blue-collar workers and drama critics who had died of various causes and met each other in the afterlife discovering that they had common children. The process ended similarly on the intuitive impulse to join hands and sing a joik in Swedish.

Azzam – the Lebanese falafel, hummus and kebab restaurant that became the venue for our finale – is one of the legendary places in Neukölln. It has probably received good reviews on TripAdvisor or somewhere in the past years, as in addition to local Turkish and Middle-East families, there are now increasingly more hipsters and tourists among the clientele. Men with hairy arms prepare the best hummus and baba ghanoush in Sonnenallee and come across perhaps a bit arrogant to newcomers, however, as you start coming there more often you learn to enjoy the rough treatment accompanying the good food. When you eventually plant your hands into the creamy eggplant cream while sharing the table with a Turkish family celebrating a birthday, everything is in place.

Although Berlin may come across as the capital of tolerance due to the various forms of diversity, it also has its controversies. In recent months, several videos have been circling in social media featuring policemen in full uniform using excessive force with one person – who is mostly a person of colour. Stories are told among friends about a person being beaten in the police car as he did not speak German – after getting into the police car for standing up for a transwoman.

No matter how wild Berlin may seem, the state is always present. The state kicks you out of the park at dark to lock the gates, the state patrols your street if you and your neighbours are not white and the state daily sends you a new notice with a claim or a bureaucratic procedure. On the one hand, Berlin is characterised by a convivial mentality of going with the flow, on the other hand, I have never had to deal with so many public officials as in Berlin. For instance, while spending a summer in Berlin a few years earlier, I shared a room and a half with about five Estonians with the occasional friends staying with us for the weekend to party at the techno music mecca Berghain. In the first two weeks after moving in, the gas was turned off as I did not have the four hundred euros demanded by the gas company guy behind my door – the owner of the flat lived in New Zealand and had not bothered to pay the bills. Soon after that we were visited by the police to hand over a thousand-euro parking fine although none of the residents of the flat owned a car. The shower had been broken ever since we moved in, so the shower cabin was equipped with a hose conducting cold water from the kitchen sink. And on top of that, the previous tenant threatened to take away all his furniture at highly short notice. Every time it seems to be getting out of hand, Ordnung reminds you of itself, however, much like in those bumpy cycling lanes, there are plenty of wild sprouts also in the pavement of rules.

PIRET KARRO is a freelance cultural critic whose love for brushwood dates back to her studies of semiotics when the periphery and Non-Tartu were held in high esteem. She then worked for four years as the culture editor of Müürileht, the largest youth culture magazine in Estonia, residing the last year in Berlin. At present, she is pursuing her Master’s studies at the Department of Gender Studies in the Central European University in Budapest.

PHOTOS by Rasmus Jurkatam

PUBLISHED: Maja 95 (winter 2019), with main topic Drift