Over the course of the past thirty years, designing school spaces has migrated from being a marginally positioned subject matter to the centre of focus in the field of architecture, supported by scientific studies and continual research and development. The spaces for learning have acquired a new image and meaning.

To understand the scope of and reasons for the changes that have occurred in and around school spaces over the past thirty years, we must go back in time and find out when the education reform began in the first place. Turns out, that is not an easy task. Basically, we might say that reforming education (like all other areas) began with the reinstatement of independence of Estonia. An important milestone was the year 2003, when the state issued tasks, ordering the counties to compile development plans for the school network (including, dividing the school districts, and naming the service centres where schools had to remain). The 2005 analysis1 compiled by Praxis on organising the network of general education schools noted the level of confusion and the complexity of the problem, while also using the situation as a proposed steppingstone for the state to accept responsibility for the long-term development of the school network and suggesting more active intervention to integrate the educational policies with regional policy-making, thus ensuring equal quality in education across the country. It was the first time when the term ‘school network optimisation’ was used, and a proposition was made to divorce state high schools from middle schools by dividing the administrative load between the state and the local governments (the state assuming responsibility for the high schools and the local governments for the middle schools). In 2009, the proposition became a legislative amendment, and in 2010, State Real Estate (hereinafter RKAS) organised the first architectural competition to build a state high school in Viljandi.

Reality of newly independent Estonia—an outdated school network

Finding articles on the topic of school architecture in the architectural journals of the 1990s is like looking for a needle in a haystack. The architectural journal Ehituskunst reports on no schoolhouses whatsoever (except for Kolga School built according to the 1985 project by Maarja Nummert, construction completed in 1991). In the architectural review Maja, only a few schoolhouses are featured in between the private homes, apartment buildings, office buildings, and commercial centres (Linnamäe Middle School by Alver & Trummal, Rocca al Mare School by Urbel & Peil), some extensions (Nõmme High School by Siiri and Margus Koot, Otepää High School by Toomas Rein), and renovation projects (Tallinn English College, Tallinn French Lyceum, Gustav Adolf School, Tallinn Secondary School of Science, Ristiku Middle School), many of which are mentioned here and there but only a few are recipients of closer inspection. This reflects the condition of a state in the process of acclimatising to a new societal order—building occurs where there is access to resources. Schools and other public buildings must wait for the state to become more affluent.

The first article dedicated specially to schools, written by Piret Lindpere, was published in the architectural review Maja not until the last issue of the decade.2 The review article does not yet associate learning with spatial solutions; the themes circle around the symbolic meaning of schools, the financial difficulties following the restoration of independence, the emptying rural schools, and some notes on the changes in the styles of school architecture after the reinstatement of independence (from the end of soviet-era postmodernist-vernacular concepts to the new ‘bold modernism’, marked by the Linnamäe and Rocca al Mare schools).

Site introductions include pragmatic architecture-specific descriptions of the location of the schoolhouse, layout of the volumes in respect to the cardinal points, spatial structure, lighting conditions, and the main materials—mostly recorded by the architects themselves. Renovation projects convey more on the historical details and colours that were preserved, developed, or changed altogether.

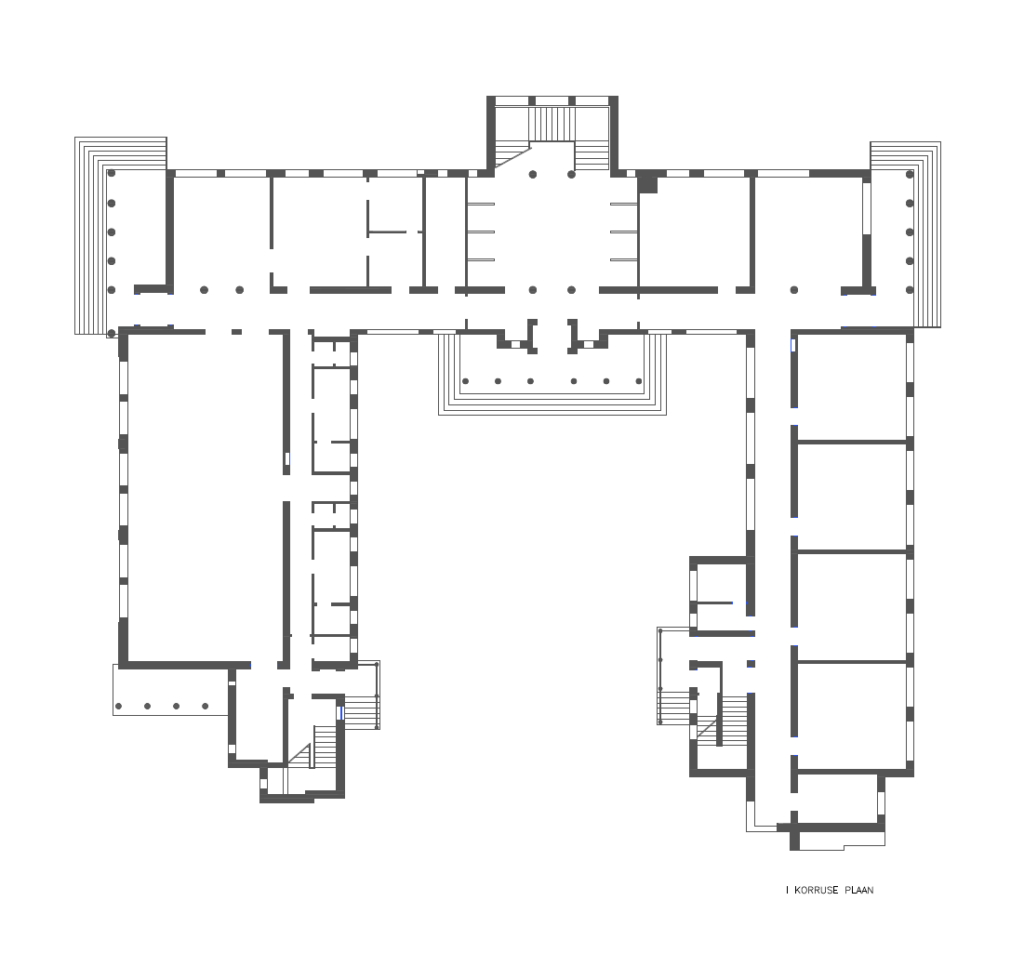

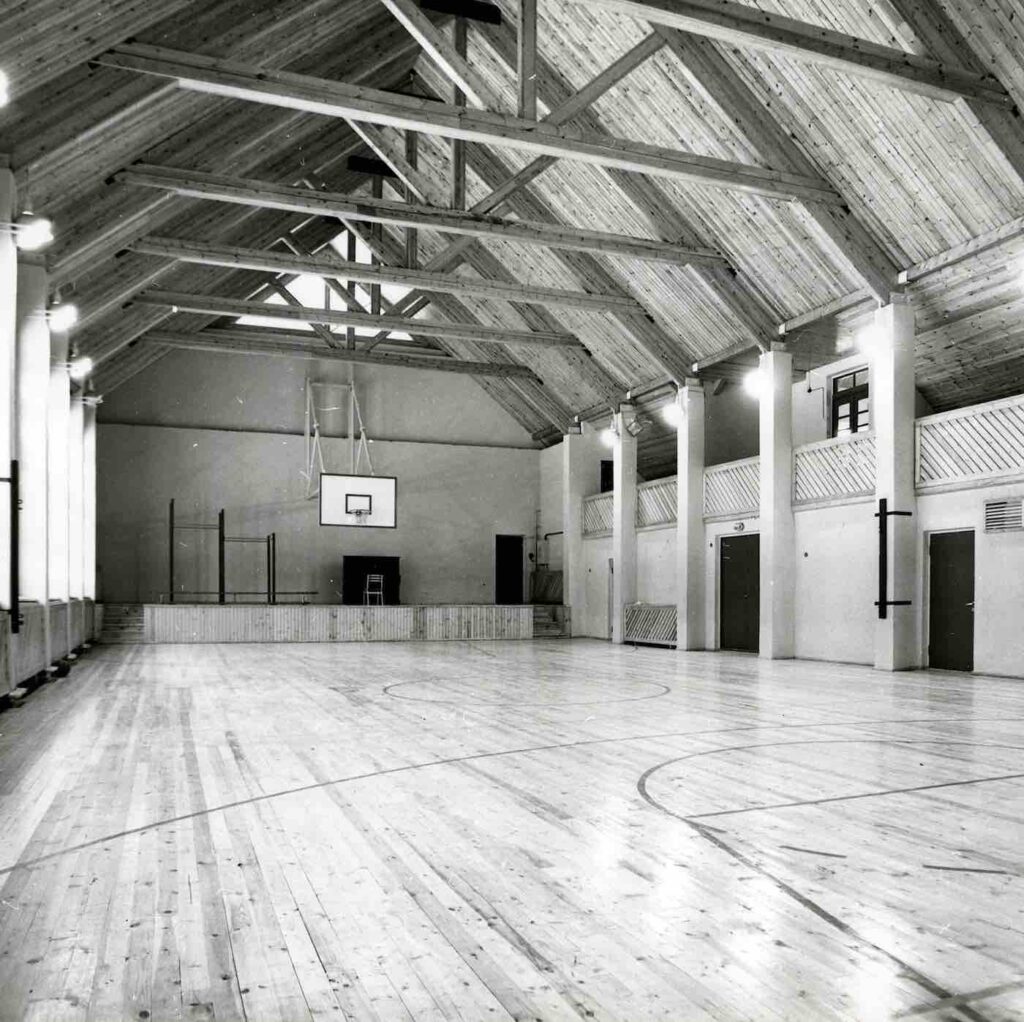

Due to many smaller schools in rural areas being in extremely bad or even life-threatening shape, the privileged position of the elite schools of the larger centres is criticised in terms of renovation order. At the same time, the value of historically important buildings being restored is acknowledged. The financial situation of universities seems to have been better, more renovation works could be afforded, and even new buildings built, but they were also considerably less in number compared to general education schools. Rural schoolhouses whose architecture relied on the 1980s’ rural building traditions are underscored as business cards of Estonian architecture of that time, most of which had been authored by Maarja Nummert whose distinct signature in schoolhouse architecture is recognisable to anyone who has taken a road trip around Estonia. They differed from the normative schoolhouse type mainly due to their dimension and vernacular style: 1–2-storeyed, gable-roofed, often symmetrical, heavily glazed, and featuring symbolic pillars in front of the main door as appropriate for a ‘temple’ of education. Their layout still resembled the typical larger schools where the defining element of spatial structure was straight hallways with classrooms indistinguishable from one another. Similar buildings from the same architect were created in the 1990s as well: the schools of Ääsmäe, Uhtna, Püünsi, Kiigemäe, and Tahkuranna.

Catalogue data from the journal Projekt ja Ehitus indicates other architects’ involvement in schoolhouse design throughout the decade as well: Krabi School (by Kalju Kisand), Himmaste Primary School (by Agu Roht), Maaritsa Primary School (by Kaie Moorast), Aravete School extension (by Ignar Fjuk), Haanja School extension (by Ilmar Jalas), Mõniste Middle School extension (by Vadim Tšentropov), etc. The journals do not, however, feature more detailed analyses on these buildings.

(Not) noticing user experience

How a student feels while at school, and how the new/renewed space impacts on learning ability, was not in focus in the nineties. Lack of attention to user experience was not isolated to school contexts—the 1990s’ paradigm often left the user out of the equation of making and writing about architecture. It was a time of transition, where the architect was still prevalently positioned as an artist, and conscious efforts were made to stand out or juxtapose oneself to the trivial mundane (or at least, to create shifts); at the same time, a new role was beginning to get imbued in the specialty—the architect as an entrepreneur and service provider. An architect’s work can currently also include social research or collaboration with scientists, involvement of the user, or research as a method.

Learning from user experience was an unacknowledged or explicitly rejected subjective approach to spatial design not to be taken seriously in Estonia or elsewhere in the world. Thus, it has been up until recently that very little has been known about the potential of the swiftly evolving branches of science researching the human being, such as psychology and neuroscience, to support the quality of spatial design. 2017 saw the publication of the book, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives,3 which highlighted the importance of the impact of space by drawing on the aforementioned branches of science. At the same time, the book maintained a critical note on schools of architecture that failed to sufficiently involve that available knowledge. The author, American architectural critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen, argues that the effect of the built environment on human beings is significantly greater than previously thought; at the same time, scientific studies seem to indicate that 90% of our daily environment remains unacknowledged.4 For example, a multifaceted, articulated school environment encourages interaction, initiative, curiosity, and physical activity, whereas a monotonous space has the opposite, inhibiting effect on those qualities. The question becomes, what kinds of environments we wish to create for ourselves and our children for learning and development. The human ability to adapt is remarkable, including to clearly harmful environments without our conscious awareness. Long-term exposure to deleterious environments has a negative effect on mental and physical health. Therefore, we must draw much more attention to architecture and landscape architecture, taking into consideration user-experience and scientific studies, and ensure general improvement in spatial literacy, so that every child and youth could receive at least a base level spatial education—to be prepared to notice and value, and ask for higher quality space in the future.

Changing content of school space

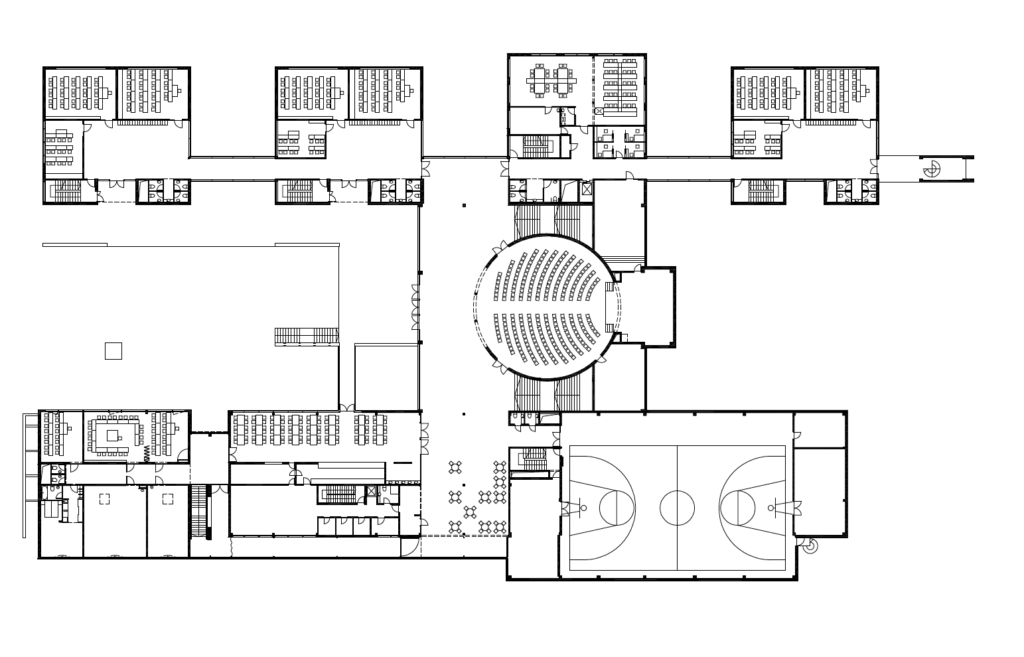

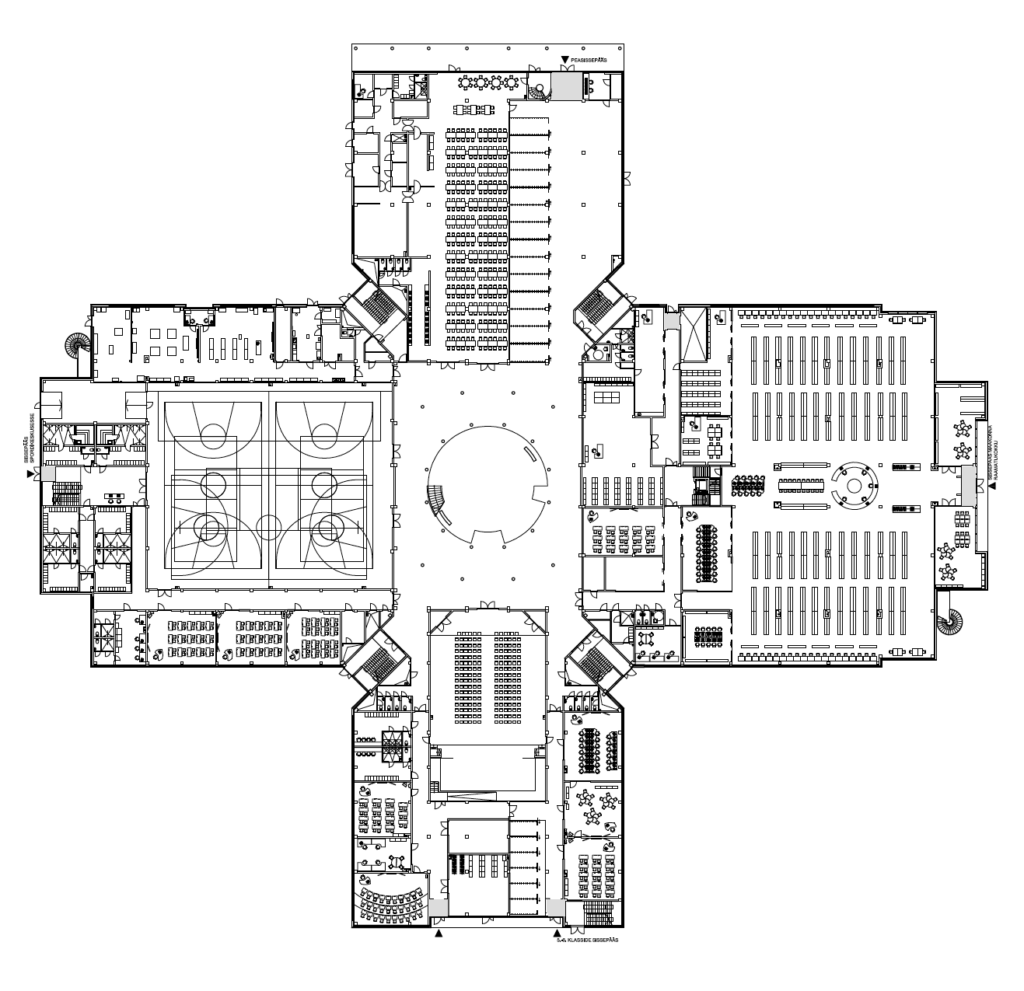

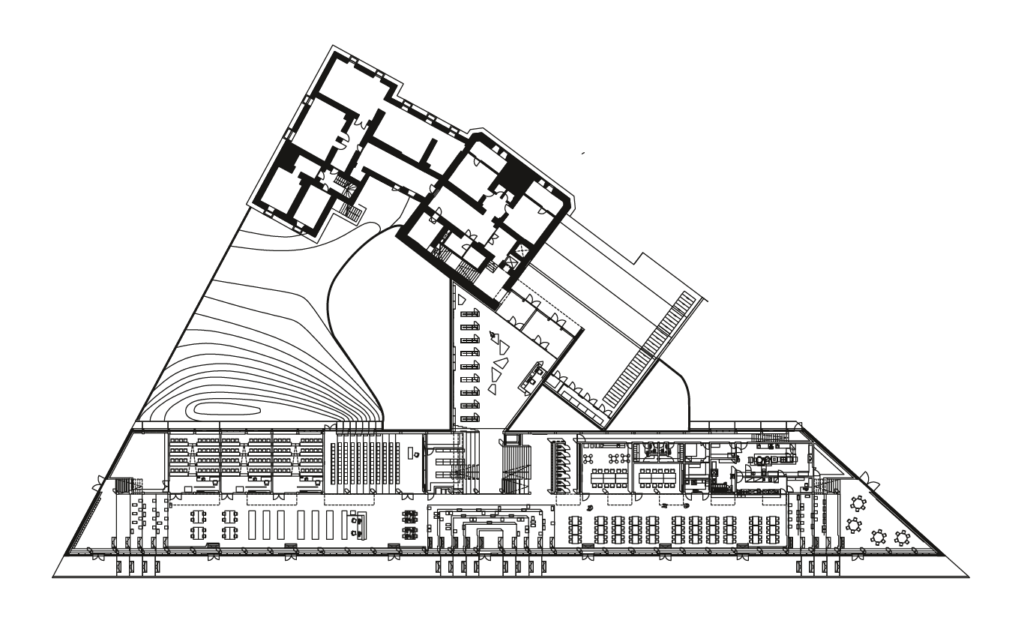

The turn of the century brought along an increase in the number of articles on schools and their content changed as well. The year 2003 and the new Viimsi High School, a winning competition entry by Agabus, Endjärv&Truverk Architects, were significant: for the first time, the project description addresses learning through the prism of social experience and highlights the importance of the atrium as a carrier of the concept of openness and binder of the school into a whole. Markers of contemporary learning concepts in the winning entry are introduced after a long foreword, pregnant with metaphors (wheel of sun, oak crown, dispersed continents connected by a light space), but the new principles are nonetheless present. Many of the spatial solutions that have been formulated by today, which support a changed approach to studying and learning, have been explicitly listed in the Viimsi School: the central atrium adjoining the canteen and cafeteria, and a wardrobe that is not hidden in the cellar but brought close to the entrance so as to encourage outdoor lessons and outdoor breaks; there is mention of nests for various school levels, the school space itself is bright and well illuminated, articulated, and varied. After completion of the building, Regina Viljasaar in her article5 emphasises the idea of mobility and sense of togetherness, contoured by the organic nature of the architecture. Praising the finely tuned discreetness and learner-friendly nature of the project, she underlines studies from the USA that confirm that children’s academic results, physical aptitude, and concentration ability have been proven considerably higher in new or renovated school buildings, compared to unrenovated buildings. She also highlights that, while in the earlier modernist tradition, children would be abstracted into ‘units’, the contemporary school at Viimsi clearly opposes this calculating worldview. Lastly, she verbalises regret that the outdoor areas of the school were not built, although the project for them existed.

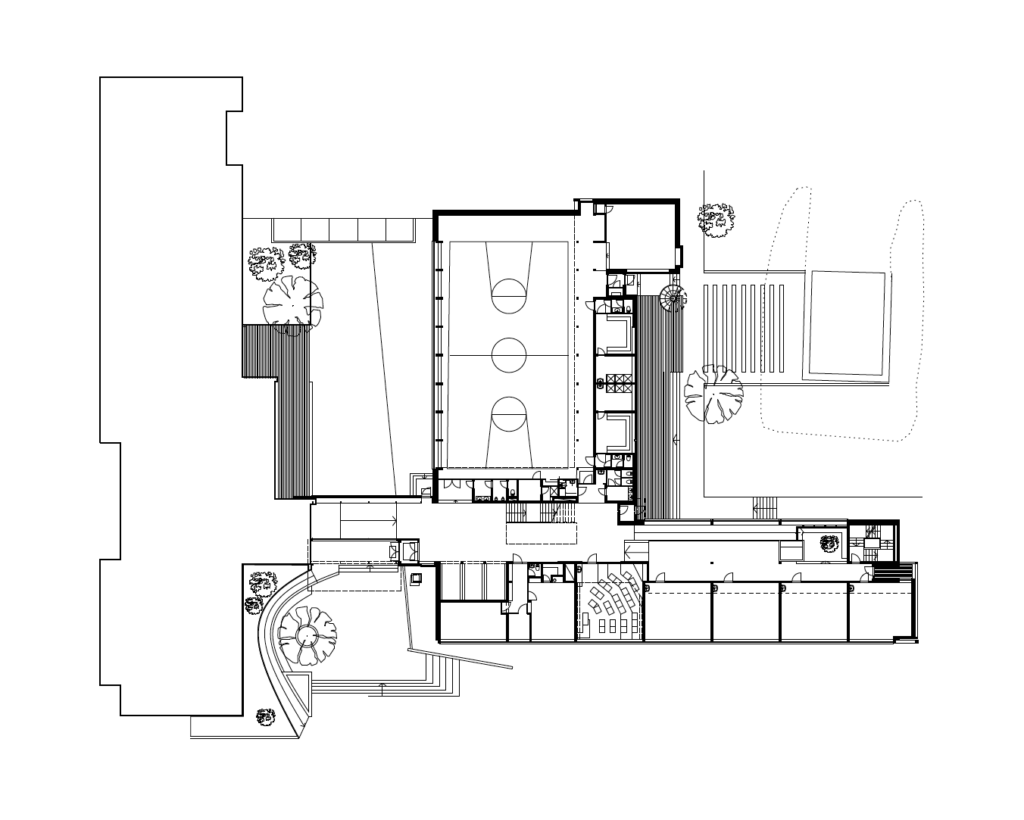

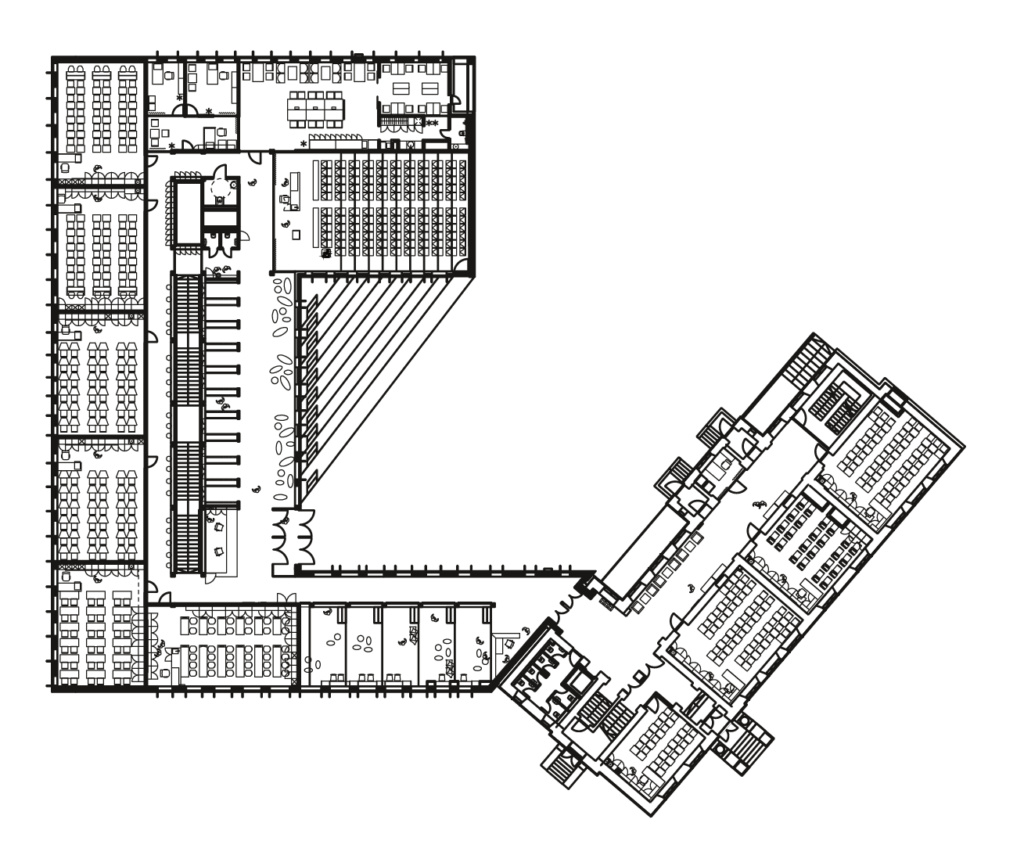

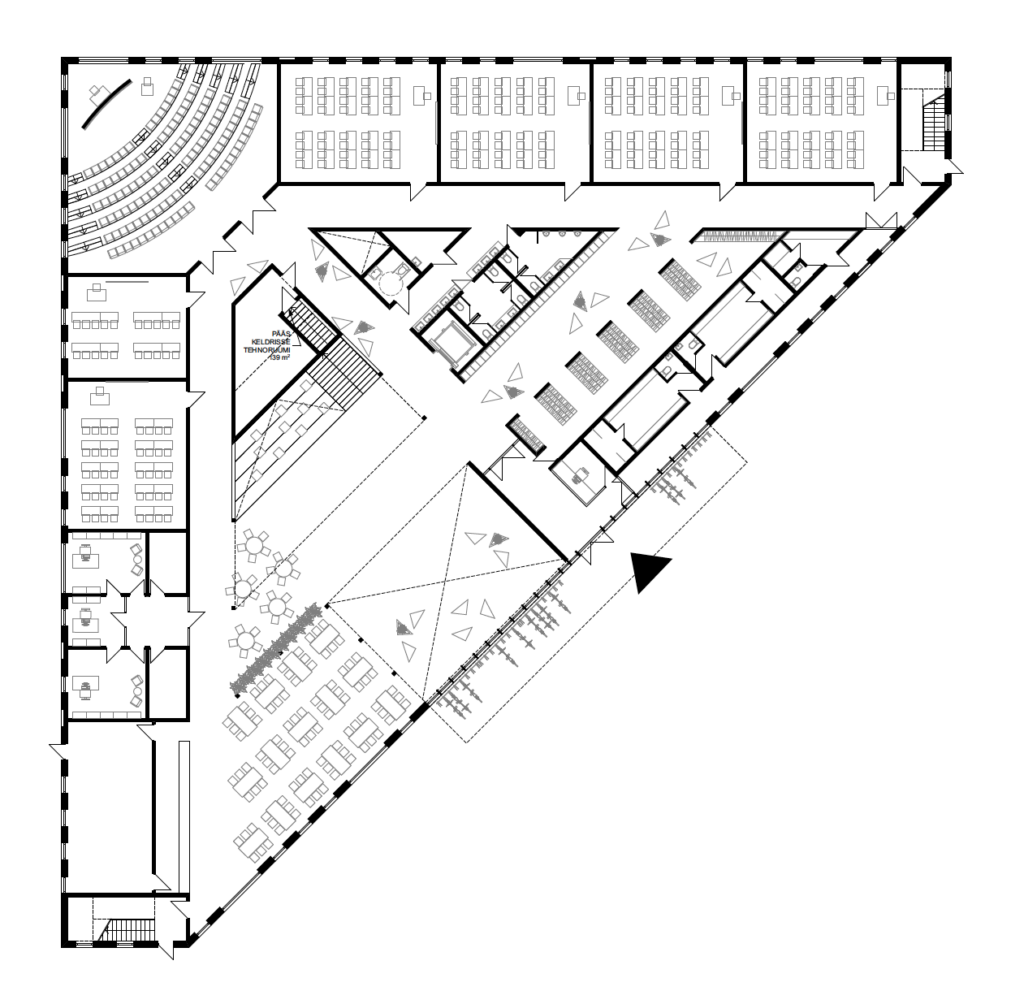

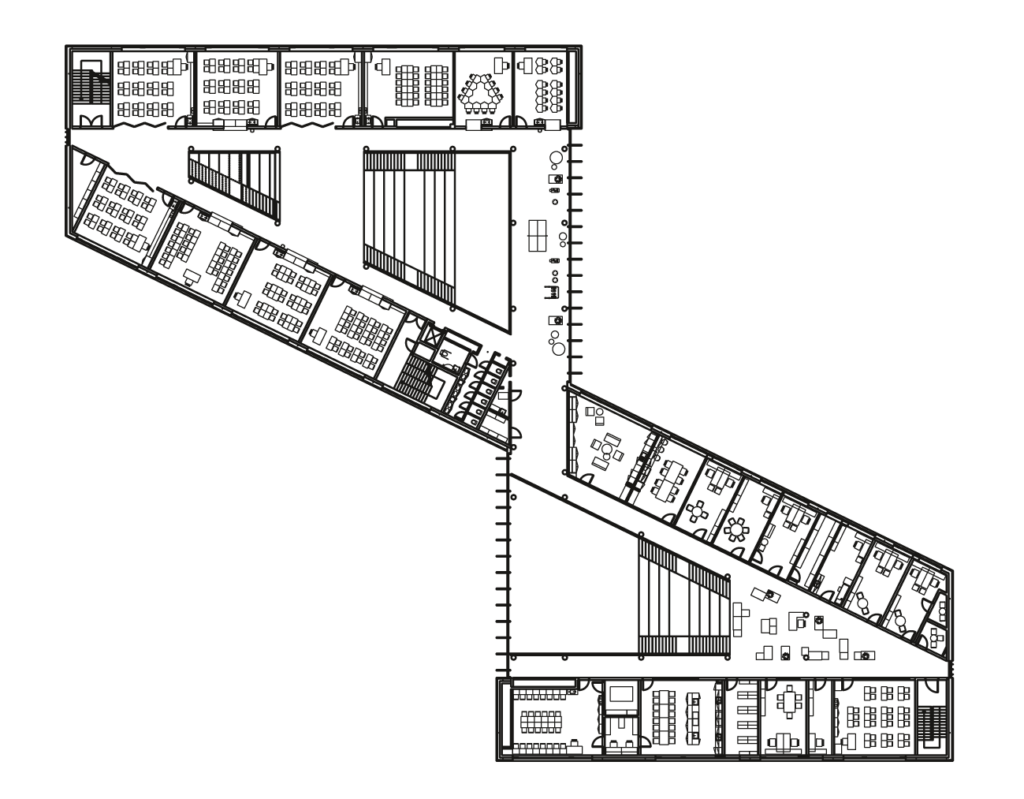

The competition for Tartu Kesklinna School took place in 2005, which was won by Salto Architects, and which opened in 2007. The site-specific architectural solution ties together the various parts of the school complex that had been completed over the course of time and creates a playfully varied whole. For the first time, the solution employs the roof area of the building—as an outdoor auditorium which organically connects to the surrounding park area (it would take time to actively implement it, since for the first few years, the steps were fenced to control access). The school extension also portrays several updates towards a new concept of learning—entrance to the schoolhouse has been brought to the rear part of the building, creating a cosy space for interaction and play in front of it; the wardrobe is situated straight across from the entrance to make grabbing shoes and jackets even more convenient while heading outdoors; the hallways feature rest areas and spatial elements with different moods; the partitions between the classrooms are movable.

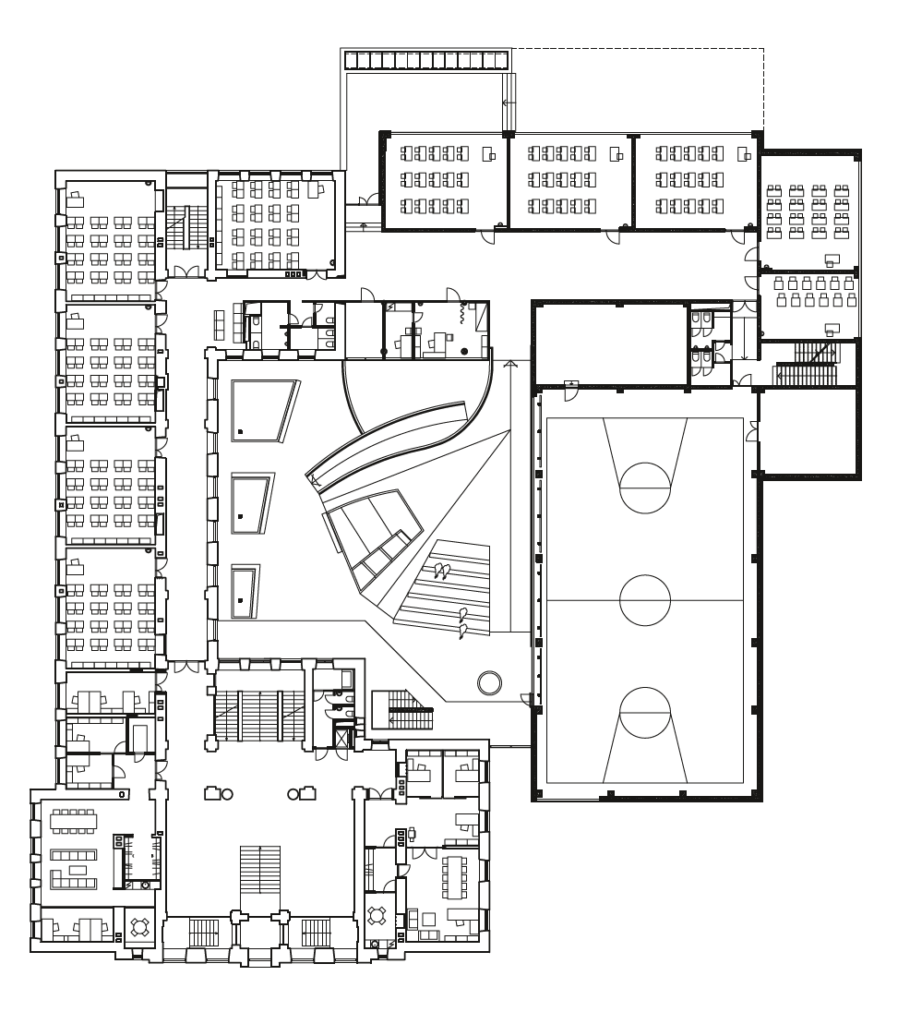

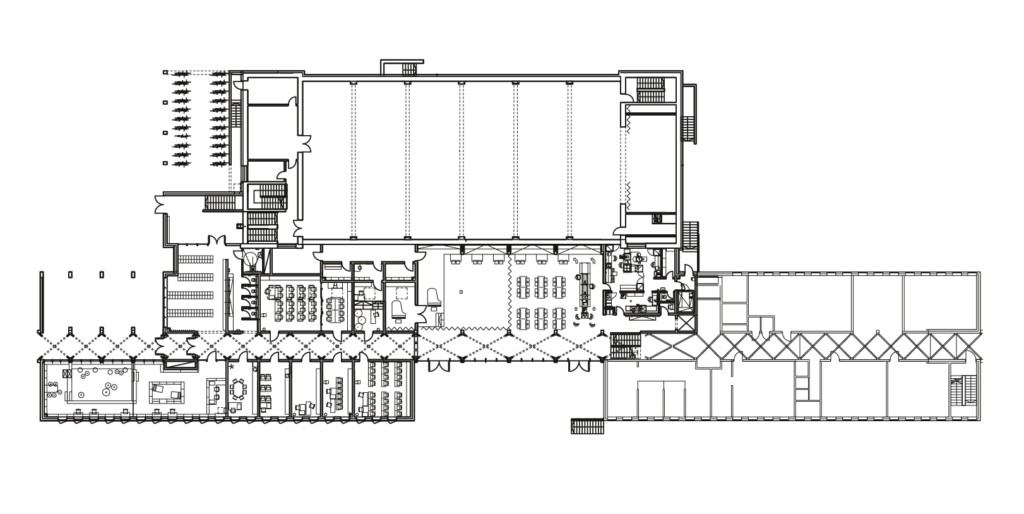

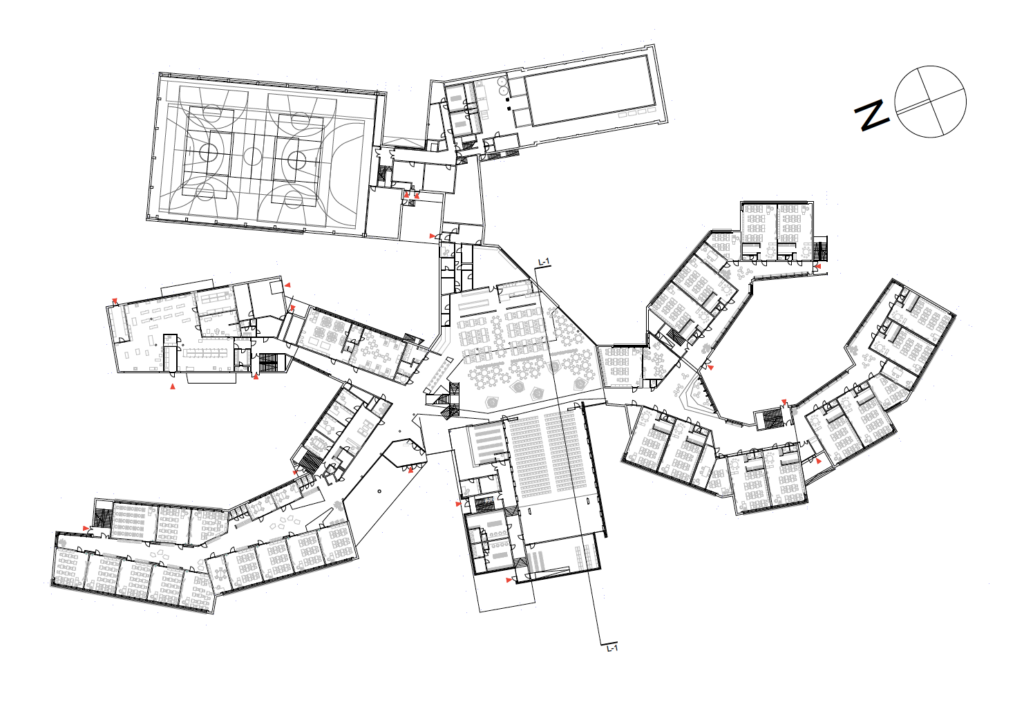

The third decade after reindependence further places the subject matter of general education and schoolhouses at the centre of focus. A new milestone emerges in the form of the first state high school in Viljandi, completed in 2013, again authored by Salto Architects—since then, RKAS as the founder and manager of state high schools has designed nearly all of the new schoolhouses through architectural competitions. In addition, that first ‘sample school’ is most often accessed as the model for what a contemporary school space should be like. The school in Viljandi is a prime example of flexible spatial solutions that adhere to the new concept of learning, especially in the atrium that connects the classrooms of the extension, which is itself a space integrating a library and a cafeteria, while enabling activities from across the board: from interaction, dining, resting, and reading, to concerts, lectures, and chemistry experiments. The façade that follows the curvature of the landscape features many doors to create opportunities for stepping out for a breath of fresh air at any given moment. There are regular classrooms as well, but it is the atrium that allows many additional opportunities for teachers as well as pupils. The key to a new school, no doubt, is also a headmaster with a vision to create an open and innovative school.

Education reform and explosion of architectural competitions

After completion of Viljandi State High School, an increasing number of schools began to reach the construction phase. In 2014, Pärnu Sütevaka High School was opened—an extension (by Öö-Öö Architects) tied to an historical building by a gallery and skilfully packed within the dense urban environment, Rapla State High School in 2018, also an extension of an old building reaching out to the park landscape and creating a cosy square between the old and the new schoolhouses (by Salto Architects), and Viimsi State High School in the same year, whose cascading wooden volume will be built on the grassland next to the expanding, newly developed residential area (by Kamp Architects). 2019 saw the completion of Kohtla-Järve State High School which works well and connects the somewhat dispersed apartment building district by creating an inviting public space in front of the compact schoolhouse (by Boa Architects). All of these schools offer intriguing site-specific spatial solutions and a versatile study space inside the schoolhouse. Coincidently, all of these solutions were selected via architectural contests.

A great indicator to follow along the trajectory of evolution of educational spaces is open architectural competitions: seeing that before the year 2000, only a few competitions took place, from the turn of the century up to today, 40 architectural competitions for schoolhouse designs have been organised, supported by the involvement of the Estonian Association of Architects. A culmination of contests was achieved in 2019 when there were twice as many competitions for schoolhouse designs in one year than in the years of the first decade of the century put together. Numbers reflecting competitions are a marker of growth in trust towards the format of the architectural competition on the one hand, and on the other, they signify that the education reform has reached the phase of physical upgrading of school infrastructure.

One of the main objectives of the education reform is to coordinate the positioning of the school network according to where people actually live. In smaller regions, that usually means spatial contraction, in larger centres it means building extensions, or entirely new schoolhouses, from scratch. This grand-scale optimisation can be viewed critically as force-extinction of smaller rural areas, but mostly it is a lag-process where schools are concerned—people have already left the area and a school with only a few pupils is unmanageable, i.e., a sufficient level education cannot be delivered. The main changes that have occurred are conversions of intermediate-sized parish centre schools: from high school to middle school, or from middle school to primary school. The turn of the decade will see the opening of numerous middle schools with innovative spatial approaches: Türi Middle School (by Karisma Architects), Tabivere Middle School (by Architect Must), Haapsalu Middle School (3+1 Architects).

Difficulty of change

Change and evolution are inscribed in learning. It is, therefore, rather peculiar that the school is one of the utmost inert establishments, albeit its task is to prepare its current students for the future of which we know so little. Sir Ken Robinson, the British researcher and advocate of education, has referred to this contradiction between the rigidity of the education system and a future that is changing at an accelerating pace, and set three requirements for the education system: versatility in the subject matter and methods of learning, arising curiosity, and awakening creativity. His impressive lecture titled ‘Do schools kill creativity?’ is the most popular TED talk throughout time among the viewers of the series.6

Most Estonian children are currently still studying in schoolhouses whose typology originated in the soviet era—the buildings fulfilled the expectations and requirements of the society of that time but are rather divergent from the expectations of our current society. The education reform in Estonia was initiated nearly two decades ago and it has taken that long to start to witness the content and structural change that it involved. At the same time, we can see that the schools have been swift and flexible in reorganising their work during the pandemic. The question then is rather about the incentive that would inspire experimentation with the new. What would be the driving agent towards more clever ways of utilising school space and being more courageous in redesigning them? Institutionally, the backing has come in the form of the state’s initiative to build state high schools and the Innove subsidies to local governments to upgrade middle schools. There have been many initiatives from the schools themselves, starting from reorganising the school day (later starting time, coupled lessons, long outdoor breaks, etc.), a bolder and more diverse use of school spaces (using the library or hallways for study purposes, opening the main hall for ‘dance recess’, active recess, etc.) up to reconceptualising outdoor lessons. Quite a lot can be changed without great expenditure. Where more comprehensive and fundamental spatial alterations are considered, it makes sense to spend the money as wisely as possible—by beginning with defining what a contemporary learning environment means.

Spreading the new concept of learning

Reiterating the reference to Goldhagen above, our daily space impacts on our behaviour, interaction with others, and thought processes to a considerable degree—the tremendous influence that school spaces have on pupils and teachers alike reaches the fabric of society, as it affords them the leverage to handle situations outside of school and in life, after graduation. In a rapidly changing society, openness to change and readiness to learn become a life-long stance. Since to a large degree, learning is a social activity, and a considerable part of education is acquired through informal means, i.e., via communication and daily activities, it is even more important that the school environment support interaction among people—the ability to find common ground, discuss with peers, younger and older pupils, as well as teachers, and parents. In other words, collaboration is key. An education system as we have known it so far, which is built upon individual accomplishments, does not support social cohesion, and may instead weaken and subvert it.

All changes to the school space that are derived from the new concept of learning cannot be evoked by mere means of a general strategy or technical precepts. They must also be animated by spatial solutions. As per the national curriculum for middle schools, the study environment is a combination of the mental, social, and physical surroundings that envelop students. It would be both unreasonable and impossible to separate one part from the whole. In changing circumstances, architects, on the one hand, need more knowledge of the operating principles of contemporary schools, and school managers and teachers, on the other, need to see (and welcome) the new spatial opportunities that architecture can provide.

All things considered, 5–6 years ago, the EAA began being more vocal on the subject matter of the changing school space, and entered dialogue with different ministries, local governments, schools, teachers, and pupils. Board representatives from the EAA invited themselves to meetings held by the Ministry of Education and Research on the topic of the school network, to discussions and debates held by the Innove grant fund on the fiscal decisions concerning middle schools, organised a conference on the topic of the changing school space in collaboration with the ministry in spring of 2018, and a year later, published a handbook7 under the same title, which was a guidebook compiled by Kadri Klementi, Katrin Koov, and Terje Ong, comprising the best knowledge and practice available at that time.

While initially, the need for architects’ involvement had to be proven to the officials of the government ministry, over time, the collaboration has become a natural part of the protocol. For example, the ministry is supporting publication of the English print version of the ‘Changing School Space’ handbook, which is a tool for introducing the know-how from the Estonian experience of school upgrades—abroad. While the ministry is backing the initiatives, a more intense working relationship has emerged with educational psychologists and educationists from Tallinn University, movement and health scientists from the University of Tartu, and landscape architects whose greatest wish has been to bring outdoor learning into focus. One of the initiators and compilers of the ‘Changing School Space’ handbook, Terje Ong, has a fair amount of experience in designing outdoor areas for schools and kindergartens. Collaboration with various partners began much earlier and an inspiration for the comprehensive printout version of the guide was a 2015 compilation of suggestions and examples of spatial solutions supporting mobility, titled, translated ‘Schoolhouse Inviting You to Move!’8 , a collaborative product of scientists from the Mobility Lab of the University of Tartu and b210 Architects. It is recommended to study the publications jointly, since they rest on similar principles and complement each other. Collaboration with the Mobility Lab will continue after the publications, with outdoor learning solutions presently in focus.

The past decade brought vast growth in understanding the significance of space and its influence on learning ability, ushering in a completely new way in which school spaces are seen and understood. That knowledge and experience can no longer be ignored.

Architectural competitions for schoolhouses:

- 2000 – Suure-Jaani High School extension, Tallinn 21st School extension

- 2003 – Viimsi High School

- 2005 – Randvere Primary School

- 2006 – Keila School 2007 – Tartu Kesklinna School

- 2010 – Viljandi State High School

- 2012 – Pärnu Sütevaka High School

- 2016 – Viimsi State High School

- 2017 – Laagri State High School, Kohtla-Järve State High School, Valga School and sports complex, Haapsalu Middle School

- 2018 – Tabivere Middle School, Saaremaa State High School, Tabasalu School, Kõrveküla Middle School, Rapla State High School

- 2019 – Jõhvi Middle School, Kärdla Middle School, Rakvere Middle School workshops, Paide State High School, Kohtla-Järve Middle School, Võsu Middle School and Kindergarten, Kuusalu High School, Narva State High School, Kuressaare Middle School, Mustamäe State High School, Sillamäe Old Town School, Rakvere State High School, Haljala School

- 2020 – Kolde Avenue State High School, Tõnismäe State High School, Narva Middle School and State High School, Võru Järve School, Rae State High School

- 2021 – Saku Middle School, Tiskre Middle School and Kindergarten, Tõrvandi Middle School, Kadrina High School

- Pending: Tallinn Secondary School of Science and Jakob Westholm Secondary School extensions

KATRIN KOOV is an educator at the Estonian Academy of Arts as well as the School of Architecture, and a practicing architect at the b210 architectural office. Past appointments include Chairwoman of the Estonian Association of Architects (2016–2020) and Editor-in-Chief of Maja (2014–2017). She has been a partner and co-author at the KavaKava architectural office.

HEADER: Viljandi State High School. Salto Architectural office, 2013. Photo by Karli Luik

PUBLISHED: Maja 106 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions

1 „Üldhariduskoolide võrgu korraldamine. Lühikokkuvõte“ (transl. analysis on organising the network of general education schools), Poliitikauuringute Keskus PRAXIS, Tallinn, aprill 2005, http://www.praxis.ee/fileadmin/tarmo/Projektid/Haridus/ULDHARIDUSKOOLIDE_VORGU_KORRALDAMINE/Yldhariduse_koolivork_lyhikokkuvote2.pdf

2 Piret Lindpere, „Templid sajanditeks,“ (transl. temples for centuries) Maja nr 4, 1999.

3 Sarah Williams Goldhagen, „Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives“ (Harper, 2017).

4 Amanda Kolson Hurley, „This Is Your Brain on Architecture“, 14. juuli 2017, Bloomberg CityLab (Intervjuu Sarah Goldhageniga), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-14/this-is-your-brain-on-architecture

5 Regina Viljasaar, „Liikumist armastav uus koolimaja Viimsis“, Maja nr 4, 2006 (transl. a schoolhouse in love with mobility at Viimsi, Maja 4, 2006)

6 Sir Ken Robinson, „Do schools kill creativity?“, filmitud 2006. a veebruaris, TED, video 19.12,https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity?referrer=playlist the_most_popular_talks_of_all

7 Kadri Klementi, Katrin Koov, Terje Ong, „Muutuv kooliruum. Eesti Arhitektide Liidu juhend tänapäevast õpikäsitust toetava koolikeskkonna kavandamiseks“, Eesti Arhitektide Liit, 2019 (transl. the EAA’s handbook on the changing school space for designing school environments supporting contemporary concepts of learning), Estonian Association of Architects, 2019) https://issuu.com/ingridmald/docs/eal_muutuvkooliruum_190x257mm_issuu__1_

8 Kadri Klementi, Karin Tõugu, Grete Arro, Merike Kull, Aave Hannus, „Koolimaja kutsub liikuma. Näiteid liikumist toetavatest ruumilistest lahendustest,“ Tartu Ülikooli kehakultuuriteaduskonna liikumisharrastuse käitumuslik probleemlabor, 2015 (transl. schoolhouse inviting you to move, examples of spatial solutions supporting mobility), University of Tartu, Faculty of Physical Education, Behavioural Problem Lab for Mobility, 2015) https://www.b210.ee/koolimaja.pdf