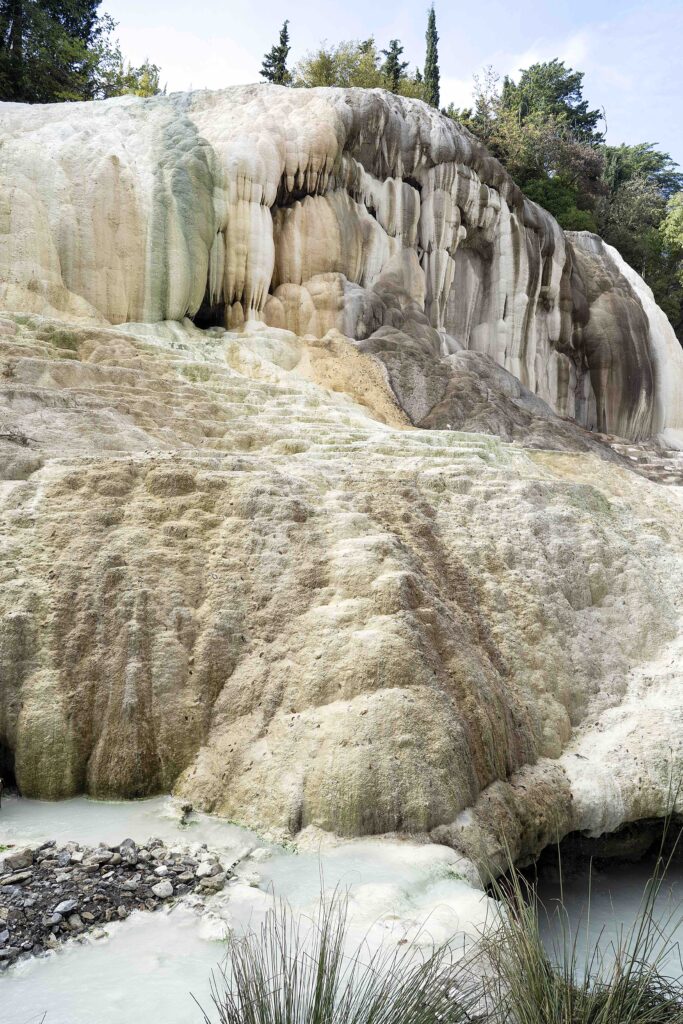

A view from Bagni San Filippo

‘The stones are alive too’ sounds like the motto of a New Age healer working with crystals in an incense-filled room. Or maybe of a mystical architect composing atmospheric buildings, playing with the arrangement of forms in the light. But it could also be the conclusion—with all the ethical questions and metaphysical considerations that come with it—of a close observation of some geological manifestations on the surface of the Earth, which have to do with the history of architecture and could have a lot more to do with its future.

When reflecting upon what tomorrow might be about in terms of architectural materiality, and especially when the imperative for ‘sustainability’ or ‘greenness’ is thrown into the equation, turning to life may feel like a safe bet. Working with the bio-sourced, with trees and plants that grow fast enough, trap carbon dioxide (our contemporary archenemy), can be planted, harvested, used and replanted in a virtuous circle of lignin and cellulose becoming buildings. The geo-sourced, by contrast, is easily disqualified by the very legitimate criticism of the over-exploitation and the global environmental damage brought about by the extraction and processing of limestone, gravel, sand, iron or bauxite to turn them into concrete, glass panes, steel rebars or aluminium sheets. The geological debt of architecture cannot be ignored, and neither can the geological abuse that has grown exponentially throughout the 20th century.1 But is there no way of thinking our architectural engagement with the geosphere differently? Beyond extraction and appropriation, can we find modes of collaboration with its flows and cycles?

In the woods around the village of Bagni San Filippo, in southern Tuscany, lives a strange geological creature, white and steamy against the green of the trees. It is a hydrothermal spring, pool after pool of milky water, populated year-round by crowds of half-naked bathers, in a haze of sulphur. People call it the Balena Bianca2, rock mound after rock mound, sometimes 10 metres in height or more, bright white in places, covered in dark green streaks or brownish mats in others. When I visited it last, in the early autumn, I also saw a lot of white oval bumps, and drawing closer to them I noticed that they were dead leaves that had just fallen from the surrounding trees. But they were completely encrusted in minerals already, petrified in a matter of days, merging with the surface of the stone. Those mounds aren’t just made of rock. They entrap much more in their mineral layers, swallowing branches and whole tree trunks, even engulfing a recently added wire fence with their not-so-slowly growing stone bodies

Reading ahead of my visit about the multiple geochemical phenomena that unfold there, I discovered that this water is heated and chemically enriched by the underground volcanic activity of the region, and that the fluid that oozes out of the ground is a solution of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2), with traces of hydrogen sulphide (H2S) that gives it the characteristic smell that sank into my skin as I was lying in one of the pools, and that lingered for days. The dark green streaks and brownish mats contain whole worlds of microscopic bacterial life growing on the mounds, accelerating sedimentation by helping the calcium carbonate go from dissolved molecule to hard sediments deposit. The bacteria end up petrified themselves, trapped into the rock, in a process of biolithogenesis—or ‘life-made stone’—which in this case produces a kind of travertine. Millions of years ago, those same dissolved molecules of calcium carbonate had been alive themselves, in the primeval oceans. They were the shells of ancient molluscs, the skeletons of ancient plankton, that accumulated to create the limestone bedrock of Tuscany before being dissolved and taken away by the spring water that flows in Bagni San Filippo. Which reminds me of the time American biochemist Lynn Margulis talked about a stone sample during an interview and said: ‘People used to think that it was just a plain rock, but we now know that it’s a skyscraper of bacteria. It was made by living organisms, many hundreds of millions of years ago.’3 When looking at stones on a geological timescale, the bios and the geos are a mere split-second away from each other. Life then rock. Then life again, then rock again.

Beside the window it opens onto the sometimes-rapid biogeochemical cycles that make stone, Bagni San Filippo also holds a legacy of material experimentation started in 1757 by local architect Leonardo Massimiliano de Vegni. There, he inaugurated a tradition of manufacturing which no longer exists in Italy but is still active to this day in a few locations in Europe. By allowing the minerals held in the water to settle for months into metal moulds designed for him by sculptor Giuseppe Pagliari, he created sedimented architectural elements called plastica dei tartari4 out of this geological process. He devised ways to add tinctorial substances to give them different colours, and to orient the flows to create veining, apparently emulating those of precious ornamental stones such as alabaster, and even replicating the white and purple clouds of Pavonazzo marble.5 With his enterprise, which was also by all means a commercial venture, he tapped into the geosphere, but not as architects usually do it. He positioned himself directly inside the ongoing cycle of stone. He went with the flow.

Acknowledging geological substances not just as static resources to be appropriated but as belonging to situated terrestrial cycles creates a new sensitivity to the inner workings of the Earth. One that opens up new terrains of creative geologies for architecture, based on collaborations between mineral, organic and cultural life in ways similar to those experimented upon by de Vegni. Beyond the sedimentations of Bagni San Filippo, new design endeavours could also observe and work with cementation, weathering, accretion, erosion, metamorphism, fusion or many more geo-dynamics, and find ways to engage not by force, but by tuning into them, in the right place, at the right time.

This speculation inevitably raises questions such as the scalability of such techniques that respect the slow rhythm of the geological. But in an architectural context that should increasingly be about building less and reusing almost everything, maybe newly produced architectural elements would no longer have to be churned out in the massive quantities and at the breakneck speed the Industrial Age has trained us to expect? Maybe geological elements used in buildings could be allowed to grow at a different pace, teaching construction to decelerate?

We architects need a geological literacy. Only then will we manage to consider the practice of design and construction not only as anchored in the deep time of the terrestrial, but also as capable of renewing itself creatively by imagining new materialities and architectural expressions out of the geosphere. A reflection that will be design-oriented, but will also be earth-scientific, cultural, metaphysical, ethical and possibly historical, touching upon how we evaluate and appropriate geological materials, and certainly opening up variegated new ways of being geo-architectural.

GALAAD VAN DAELE is an architect and researcher. He teaches design at ETH Zurich and is a co-editor of architecture and art magazine Accattone.

The essay ‘Sedimentary Flows and Creative Geologies’ by Galaad Van Daele was commissioned for the publication Reset Materials–Towards Sustainable Architecture, edited by Chrissie Muhr and published by the Danish Architectural Press (Arkitektens Forlag, September 2023). Continuing the exhibition ‘Reset Materials’ curated by Chrissie Muhr at the Copenhagen Contemporary, Reset Materials both documents and reflects on the multidisciplinary dialogues between the ten teams and materials, entangling shared learning and practice, science and aesthetics. Both publication and exhibition were realised in collaboration with the Danish Association of Architects (Arkitektforeningen) and supported by Dreyers Fond. The publication is available via the Danish Architectural Press.

PHOTOS by Galaad Van Daele

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE

1 Martin Head, Will Steffen, David Fagerlind, Colin Waters, Clément Poirier, Jaia Syvitski, Jan Zalasiewicz jt, ‘The Great Acceleration is real and provides a quantitative basis for the proposed Anthropocene Series/Epoch’, Episodes 45 (2021).

2 The White Whale (it).

3 Symbiotic Earth: How Lynn Margulis Rocked the Boat and Started a Scientific Revolution, director John Feldman, 2018.

4 Tatar sculpture (it)

5 Fabio Barry, ”Painting in Stone’: Early Modern Experiments in a Metamedium’, The Art

Bulletin 99, nr 3 (03.07.2017).