Siiri Vallner is an industrious architect, who is sensitive and attentive towards the environment, while at the same time, her projects are rational and conceptual. At the moment, with her team, she is designing Tallinn’s main street, and also working on the vision for the coastal area of the city, lately the most influential undertakings in the city planning

Interviewed by Jarmo Kauge

People know you as a humble, gentle, perhaps even shy architect, living and working in a heritage-listed wooden neighbourhood and driving around town with bicycle all year round. You do not have a smartphone, not alone a Gmail or Facebook account. Are these signs of caution towards technoconsumerism?

Not really. But these are all very conscious choices, not to possess all kinds of smart gadgets or even a TV set, to use a bicycle, to live in a building heated by wood. Actually, I have grown up in close contact with computers – my parents are working in IT. Back in the late Soviet time, they were able to pursue their own projects in the computer department of the State Planning Committee after working hours, so they had to take the kids along. We called it ‘going into the machine’. My childhood was spent in that computer department. Me and my sister, we were running around the building, and later playing the first text-based computer games.

How did you find your way to architecture?

It might be hard to believe but I was really struggling as a teen. I opposed everything, so for example pursuing maths studies was out of the question although I had graduated high school in a class with sciences specialization. I’m mostly a decent and orderly person, even too much so, but I completely ignored high school. So choosing architecture was like the only option I had. Competition for admission was tough but high school final grades did not count.

Yet something must have prompted the choice?

As a kid I used to do a lot of sports but in my teens I discovered art. Still, I was no artist. But I think this is where the interest in architecture came from. In hindsight, the choice was somewhat surprising because in the beginning of the 1990s there was nothing interesting being built at the time neither any remarkable building plans in public discussion. I imagined an architect being somebody rather introverted, quietly minding her own business somewhere. I do not like to perform in public. The buildings I enjoy are similar to the people I like – rather discreet than noisy.

University usually is the most definitive period in one’s formation. What were the most relevant issues from that time? You have mentioned the influence of 3+1 architects.

At the Estonian Academy of Arts, Alver and Kaasik were prevailing but I almost did not attend their classes as I was always studying somewhere abroad. The new era had just begun, most of the professors were the same as in the 1980s, only Tiit Masso was ‘the young one’. 3+1 architects (Markus Kaasik, Andres Ojari, Ilmar Valdur, and Inga Raukas – JK) were the first ones standing out for their different ideas at school. They had just graduated and were in their first year teaching.

But the greatest impact was a semester I spent in Denmark. In Estonia, the social aspect of architecture was practically never discussed at that time. In Denmark, the issue was a blast on me. The social relevance of space is the very basis of architecture making there. Upon returning I felt as if it were impossible to discuss it with anyone here, as if it were a taboo subject normal architects do not deal with. It seemed like a minor issue compared to the grand urban ideas discussed here. It only arrived later to claim a central importance that it occupies to this day.

How did your time in the United States follow up on the Danish experience?

I was living in Washington D.C. for a year, and in New York for a year. This was a great experience of locality an authenticity. In spite of the enormous scale of NYC it is possible to lead a perfectly locally-based life there. You may live and work within a couple of kilometres. Authenticity in the USA comes in all possible forms so it is very enlightening. As architects are always constructing new living environments we are also creating new forms of ‘authenticity’.

It seems that the aspect of locality has always played a part in the DNA of Kavakava. What is its position in your practice today? I guess you have never designed a project outside Estonia.

A couple of years ago I was attending a conference on peripheries in the Czech Republic.There were architects whose whole practice was based in one village, whose architecture was essentially local. I was deeply impressed by such an attitude and I would happily convey that image myself. But compared to them, it wouldn’t be completely true. Actually, if we had enough initiative and entrepreneurial spirit, we would do competitions abroad as well.

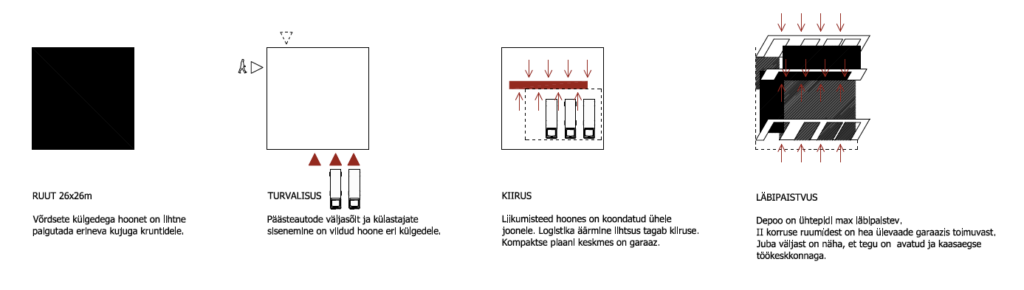

Currently one of your main projects is Tallinn main street, based on a competition design with Toomas Paaver. What is its conceptual core, how does it relate to your other projects? Or is it just a pragmatic amendment of urban public space that does not even need a conceptual approach?

This project is essentially no different from the previous ones. Our approach is still based on our core values, and the spatial solution will express these. The ideology of the main street is originally not ours but we share the idea, at least for now – you never know what direction a design project will take if politicians are involved. A city is a big organism and it is difficult to mobilize all its elements. The main street works currently as a slogan that is able to mobilize all different departments. A model street, an example for the future. At the moment, everyone equivocally backs it. For us, the main motivation is a concept of equality of all users – everyone deserves equal respect. In the context of Tallinn this is a major breakthrough.

If there is a viable conception already existing before you are involved in the project, does it make a project less interesting?

In this case, I wouldn’t say that. Architecture and urban planning are very slow disciplines. A hundred years might pass with not much happening at a certain site, and then suddenly you receive the job as a baton in a relay race where you must do your part and pass it on. There is very little consistency in Estonia. This project is an opportunity to build on something already existing, and it is heartwarming – a different feeling than the usual projects. Our favourite part concerns the bastional belt, although even this is not our original input, we just managed to bring it into focus again.

The most problematic part of the main street project is the part of Narva Road with a lot of withering businesses – does it still have any potential?

It would require a great deal of effort. Spatial manifestations of power relationships are very interesting, and Narva Road makes an interesting case. This was something we dealt with in the project for Tallinn Architecture Biennale in 2013 as well. The current situation has developed over time, it has a range of reasons. During the Soviet times it was developed as a showcase street, the connection with the seaside was blocked; later, private ownership resulted in further closing of the few passages there were. Today, the developers often like to use the rhetoric of creating passageways and openings instead of proper streets, some semi-private yards that would be universally accessible. But it will all vanish shortly, the space will be privatized. The architects should not foster illusions resulting from such rhetorics, it is self-deceit.

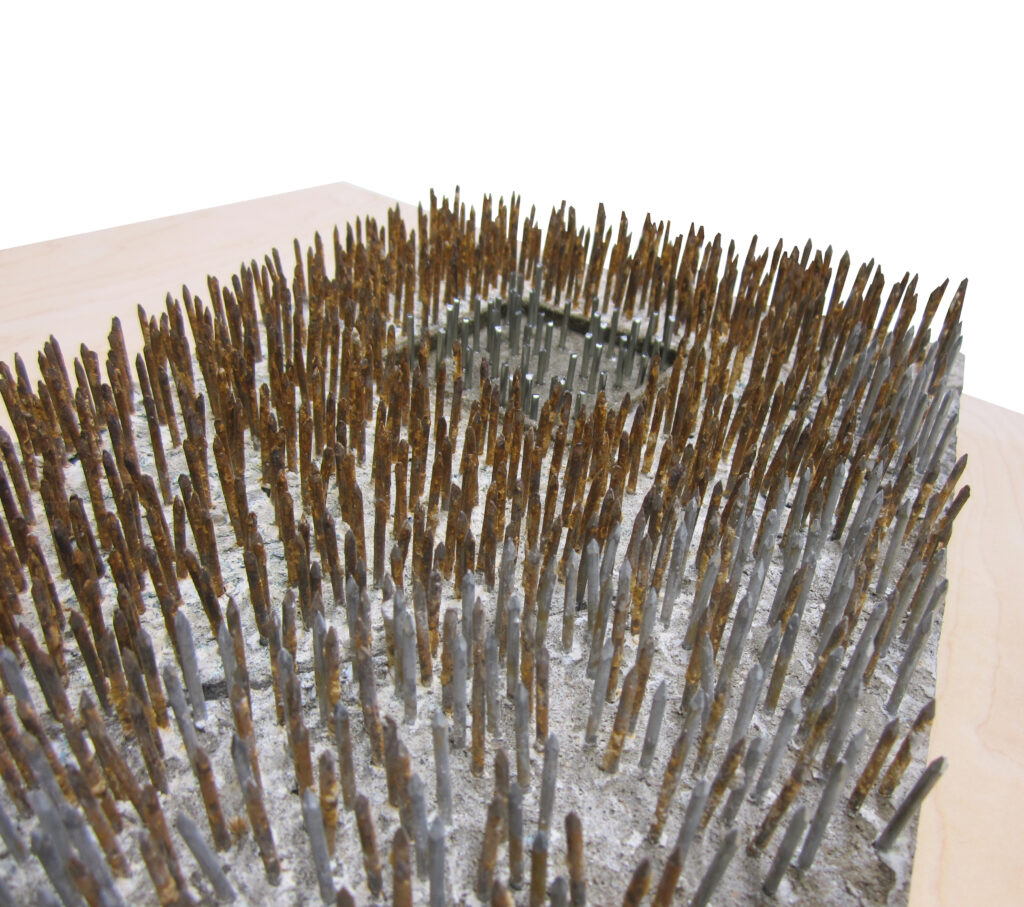

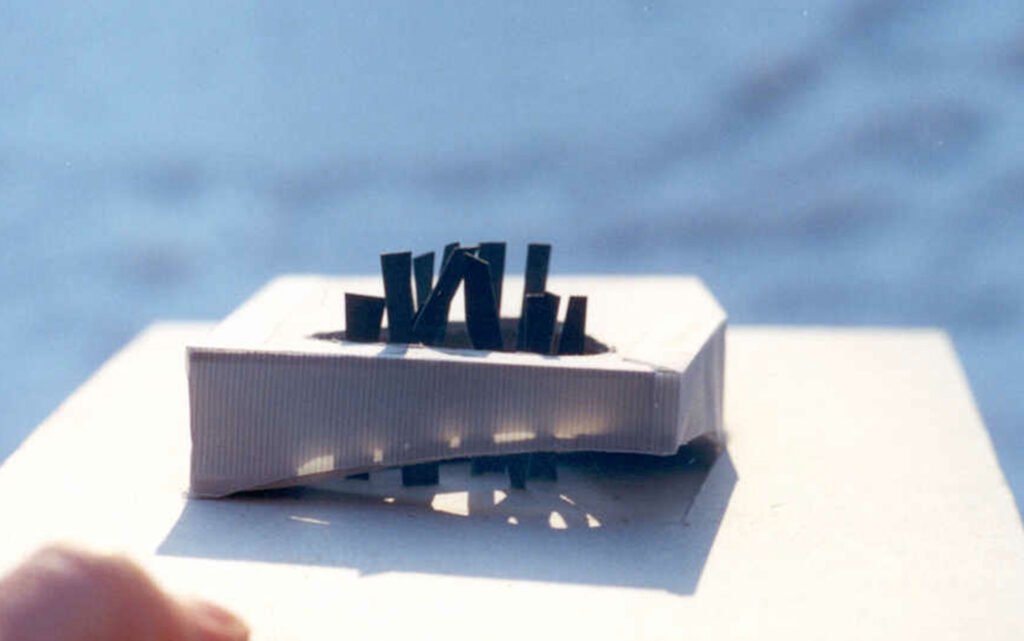

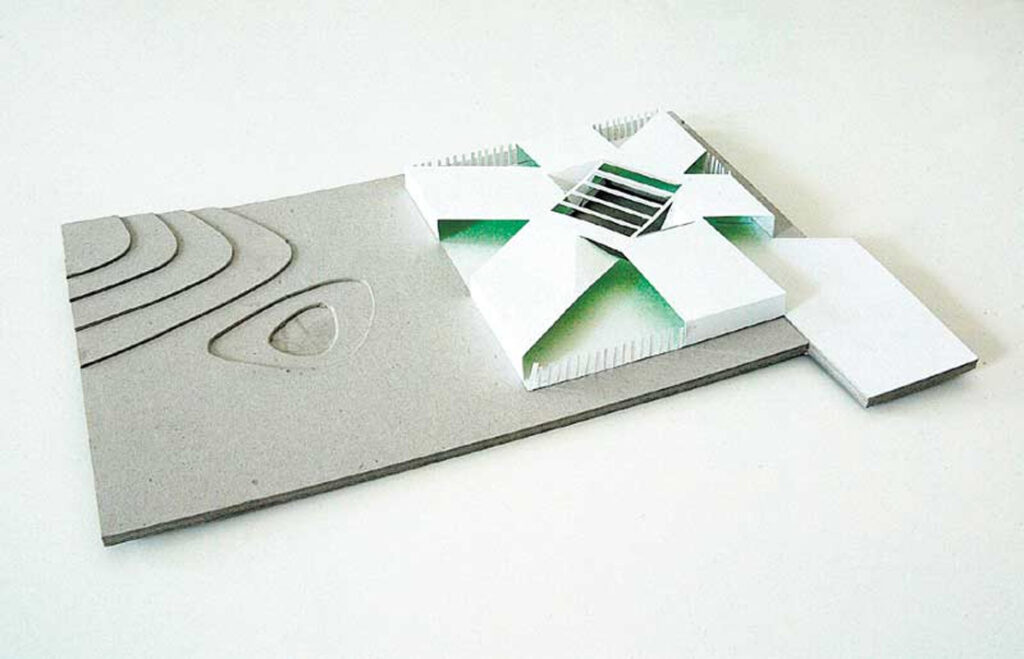

Among your recent projects, the memorial for the victims of communism at Maarjamäe, awarded the purchase prize, is most arresting. It seems like a model project most perfectly conveying the ideology of Kavakava.

The issue of monuments is an intriguing one. We instantly knew that we must participate, and we were sure we wanted to collaborate with an artist. Jass Kaselaan is an original thinker who does not have any prejudices regarding monuments as many contemporary artists do. We already had the idea to use forest but we weren’t sure how to solve the question of the wall. It was Jass’s idea to make the center of the memorial inaccessible.

It is almost an impossible task to create a monument next to the existing Maarjamäe memorial. For us it was crucial that the new memorial would complement the previous one at the same time offering a different spatial experience. There is this intense, dense and dark forest that is not really integrated to the existing memorial so intensifying its experience suited our idea. We were also considering the ceremonial protocols – laying the wreaths takes place in a similar way everywhere but it is a custom from a different era that has largely lost its meaning. Our aim was to rething the ceremonial protocols – even is the person who has arrived with an entourage of security guys and soldiers he would still experiencing the moment alone. Lately, there was a photograph in a newspaper about our president Kaljulaid laying flowers to the remains of the Berlin wall. The flowers had to be stuck into the wall joints one by one. Even this is a somewhat different experience than laying a wreath on a pedestal; a different meaning might emerge from there.

As an architect you are the creator of a space, regulating people’s behaviour. Does manipulation make for an ethical issue?

It is an ethical issue right from the beginning. Any space manipulates people, either in a good or evil way. I do not indulge in illusion of being free from it. The task of the architect is to organize the space and direct people’s movements. The question is how to do it in a way that would not deprive the user of her freedom. A moment of freedom must be retained in each project. As a user of space, it is also most important for me that a space would not be oppressive or too organized.

On the one hand, the space needs to be organized, on the other, it has to have some loose threads. How do you balance these opposing principles?

I think a space always needs to have a certain slack, a contingency that creates a certain breathing space. At the same time the user needs a hint or some kind of guidance – a space must not be too neutral, too universal. This is a reason we do not design commercial spaces – we couldn’t want to design a shopping centre where our task would be to persuade people to do something they otherwise wouldn’t. In the case of the Museum of Occupations we dealt with the issues of spatial persuasion and clearances perhaps in the most naive and eager way, it was our first project. Its space is not totally uncontrolled – the change of height induces a certain movement or behaviour. But the push is really very slight. Maybe nobody even notices.

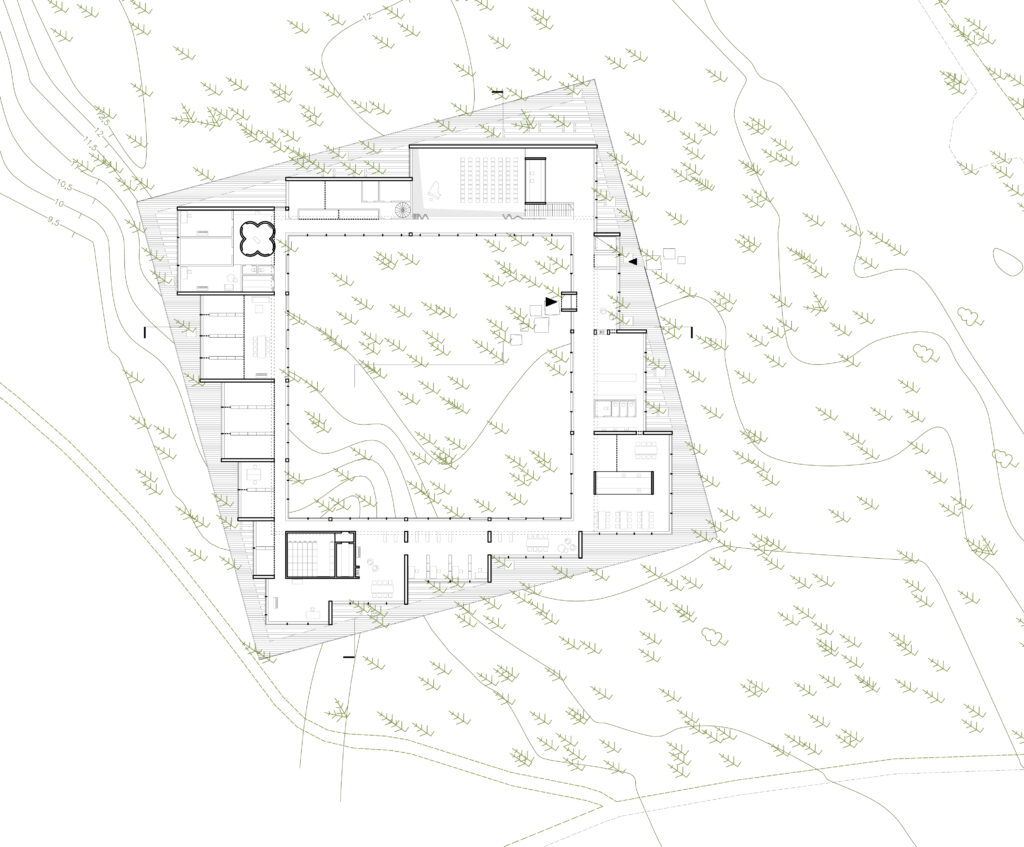

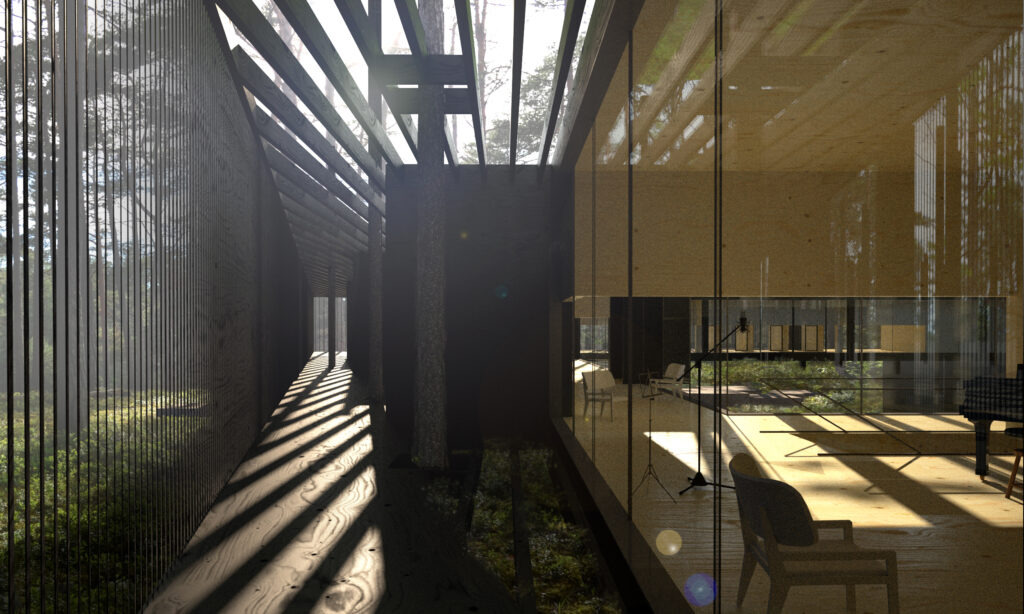

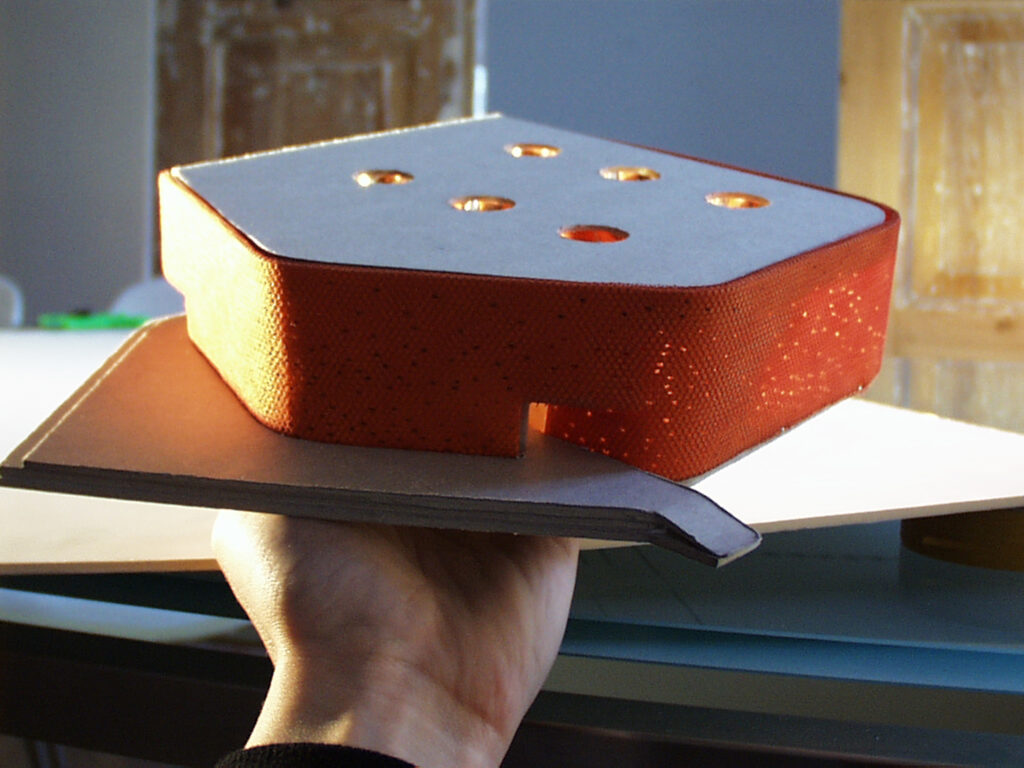

At the same time some of your projects betray a certain propensity for systems and regularity. Perhaps it most strongly reveals itself in the case of private houses but also in Lotte kindergarten, Vallimäe stairs in Rakvere, or the competition entry for Arvo Pärt centre. You mentioned 3+1 architects whose designs display even stronger systematic approach, you have also said you enjoy the work of OFFICE Kersten Keers David van Severen from Holland whose desire for systems borders on fetishism. Does the need to impose systems raise from lack of frameworks in a form of some already existing architectural substance, or strick regulations to dispute?

Maybe yes. Maybe these are the cases where a system displays itself most clearly. But generally, architecture is essentially a system. An order, a structure, or a system may be present in a more open or undisclosed manner. In any case, architecture is based on it. And it is something I’m attracted to in architecture. In the case of OFFICE, it is something like an idée fixe, quite useless – however, I wouldn’t know how it works in real space, I have never experienced their built projects. And this can make a great difference – I remember seeing some buildings by Louis Kahn as a student. I had always considered them pointless formalism but they appeared, to the contrary, totally unformalistic. A perfectly simple system or geometry may offer so many possibilities and so much freedom. And if you enter a space that might come off as perfectionon the drawings, you may be completely unaware of this quality in real space. I wish total perfection and total freedom might be compatible. But they are not. You must not push it too much. To go too deeply into the projects of OFFICE might give you creeps.

The competition design for Arvo Pärt Center by OFFICE was quite radical.

I loved it. It was one of my favourites from that competition.

Occasionally, your systematic order allows some unexpected moments. These do not disrupt the system but offer an additional layer, add a human touch. Your systems are never total.

I am soft like this – I would like to be as radical as OFFICE, or even more, but I cannot because at some point a feminine softness undermines all this radicality.

Your entry for the Arvo Pärt Centre competition was awarded 3rd prize (ahead of OFFICE), and you regrettably did not win the memorial for victims of communism competition neither the one for the Estonian Academy of Security Sciences although you fully deserved to win. How do you take losing?

I am the sportsman of the office. At a certain moment in time, someone is simply better than you, and wins. I am accustomed to it. In sports, it was made clear early on that there is no explaining away your defeats.

But in sports the results are usually measurable…

Indrek also claims that for the sake of mental health, one should think differently, and curse a lot…

You and Indrek seem like totally different personalities yet there are some similar traits as well – how does your cooperation work?

It doesn’t (laughs). Of course, somehow it does work. I enjoy cooperating with Indrek because he always brings a certain edge to the project. It feels a necessary aspect. I have been working in some other teams as well, and sometimes feared that the result will be too neat. I very much enjoyed observing the cooperation of Sami Rintala and Marco Casagrande. Rintala is soft and emotional, Casagrande is quite the opposite. The projects Sami is nowadays doing by himself are supernice but something seems missing. Indrek is always thinking everything through, he never simply utilises a fully-formed conception or makes use of a common idea – he always thinks it through from the scratch. He is against any kind of emulation. Not a single line may be drawn without a reason. If my secret hobby is triangulation then Indrek is interested in integrating music and architecture. The question of composition in general, not in any one discipline – at some basic level the tools of different artistic disciplines are similar.

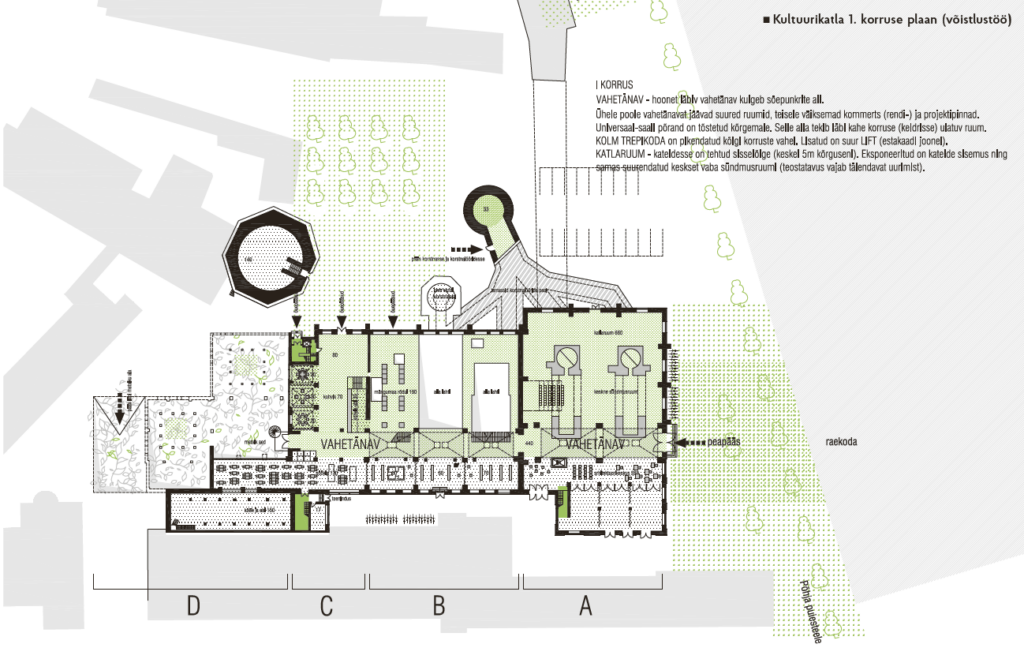

Kavakava is also well known for thoughtful, intellectual relating to existing built substance both in terms of urban planning as well as in buidling reconstructions. Your approach is often very delicate, even surgical, very deliberate, bringing out the qualities already existing. This has been the case at the Cultural Cauldron that you have earlier called a dream job although for different reasons the result was not quite like originally planned. What went astray in the process?

In the case of the Cultural Cauldron, we have seen five generations of clients – I believe the current situation is not the final one either. In the beginning there was an NGO whom we compiled a simple spatial study based on their general ideas. We were just looking at the possibilities of the space. A workshop followed, and only then there was the design competition. We almost cannot claim the authorship of the competition project because we used so many ideas from the joint workshop, it was based on a vision of the whole group. As architects we acted as curators of space. Most of what has currently been built has followed the design and we are happy we managed to assign the main role to this magnificent cauldron hall. The spatial results are quite ok apart from the demolition of the loading ramp and the wild garden. The main disappointment is the changes in use management, and the realization how easy it is to hijack a space and an image with nobody protesting.

Continuing with problematic issues we have to tackle the State Real Estate Ltd (Riigi Kinnisvara AS, or RKAS), the biggest client in Estonia that you have had to confront in a number of times. What could be done to get this system working without making architectural compromises? RKAS has been seen as rather harming than benefiting the Estonian built environment.

At the moment this is regrettably true. It is a highly technocratic and bureaucratic institution, very difficult to cooperate with. A classic case of bureaucratic idling where issues that actually matter are not dealt with. It is a system with normatives of its own but the architect appears as an anomaly in the system. The same applies for the user. The issues of organization and managing processes are an art of its own but in the case of RKAS these are highly formalized and rigid. The people employed there are quite normal and smart but in summation, the organization acts dumbly. In this machinery that is the RKAS, there should be also a firm place for the architect’s point of view so employing architects would balance the situation there. Although in the end, the institution is not essentially evil, they do try as well. The idea of integrating a competence centre for designing, constructing and managing the buildings of the state is not bad in itself.

How can one create architectural qualities in such a whirl of bureaucracy? By qualities I mean some kind of a surplus value, even spatial poetry. Your projects induce qualities that might be elusive, that defy the merely pragmatic aspects, impossible to quantify in monetary terms. Yet RKAS tends to produce Excel charts in concrete.

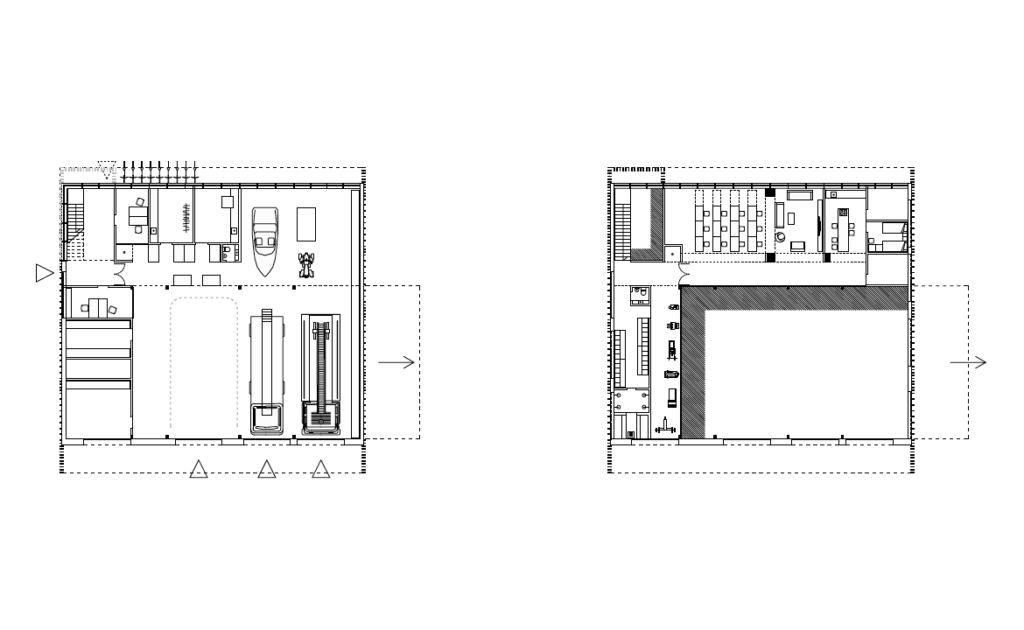

We keep quiet on these matters. If the project, designed for RKAS, has some essential qualities, something really important for us, it must be hidden so that it would not become an issue at all. Everything must be cheap yet nobody cares about the different possibilities of achieving it. At this year’s Venice Biennale there was an Alabama fire depot by Rural Studio that was extremely simple and cheap yet we would be unable to design such a solution under the regulations of RKAS. All boxes for normatives must be ticked. The system does not enable innovative solutions for achieving cheaper results.

So that a building that has to be built cheaply would actually be cheap and not try to ‘dress up’?

Actually, yes. We have a project for a fire depot in Vastseliina that is shortly being built, it is located in the middle of a forest, and there is no reason why you shouldn’t be able to open the windows – but no, they require some kind of technomiracle with a cooling system. After all, you may even leave architectural quality aside for a moment, it is not the most important point. But it is not possible to go against everything you believe in. It is not sensible to design a house, much less a standard design project, that does actually not conform to the users’ needs and will be expensive to manage and keep up. But architects don’t seem to care. In ten years it will give a serious backlash. The society changes, values change – it is due time to give some serious consideration to the issues of sustainability and cost. I think in ten years nobody undestands the present choices. But there will be no-one to blame then so the only ones who have to take responsibility will be the architects.

To what extent are you willing to fight? Go to the barricades?

I used to think of the architects as the capitain of the ship who has the obligation to be the last one standing on the sinking vessel. I’m not so sure about it anymore. But it’s a pity that the architects are not co-operating much. Building up a career is seen as serious competition instead and there are very few activities and workforms that would foster cooperation.

You have said you try to invest your designs with some positive energy, a certain optimism or brightness. Is it always possible?

It is possible. But you have to keep focusing your mind on it.

JARMO KAUGE is an architecture historian and critic, he works at the Museum of Estonian Architecture as a photo archivist and curator.

HEADER: photo by Mark Raidpere.

PUBLISHED: Maja 89-90 (summer 2017) with main topic Changing