Summer 2017: Changing

Peatoimetaja Katrin Koov.

The Estonian National Museum’s own home was completed thanks to three very simple underpinnings: belief, trust and cooperation.

Now, as the process of the rough diamond becoming an alluring (architectural) gem is complete, it is time to explore the fine cuts made to achieve it. We discuss the project through three generic terms: vocabulary – defining the key terms for the building, urban – contextualising it in micro- and macro-scales, and internal – from the interior ambitions to domestic relationships.

DGT’s architects had previously worked in large offices and their attitude in the beginning was that they’re the ones who come here and tell us how things will be. But there’s a different climate here, and for another thing, different laws, and third, different relationships in the field of construction. In France, the architect is always the general contractor, but here the tenets of the Public Procurement Act had to be followed. The position of the architect on the team is different. Furthermore, the engineers for this prestigious showpiece building had been chosen at tender for the lowest cost, and this caused problems of its own.

The renovation of 44 Queen’s Gate Terrace was completed more than a year ago, after which the embassy’s doors were also opened to visitors, whose numbers have risen impressively. A fair testament to high public interest in the building is the fact that on the city’s annual embassy open-doors day, the Estonian Embassy was so popular that the amount of people wishing to tour it exceeded the limited time frame allowed.

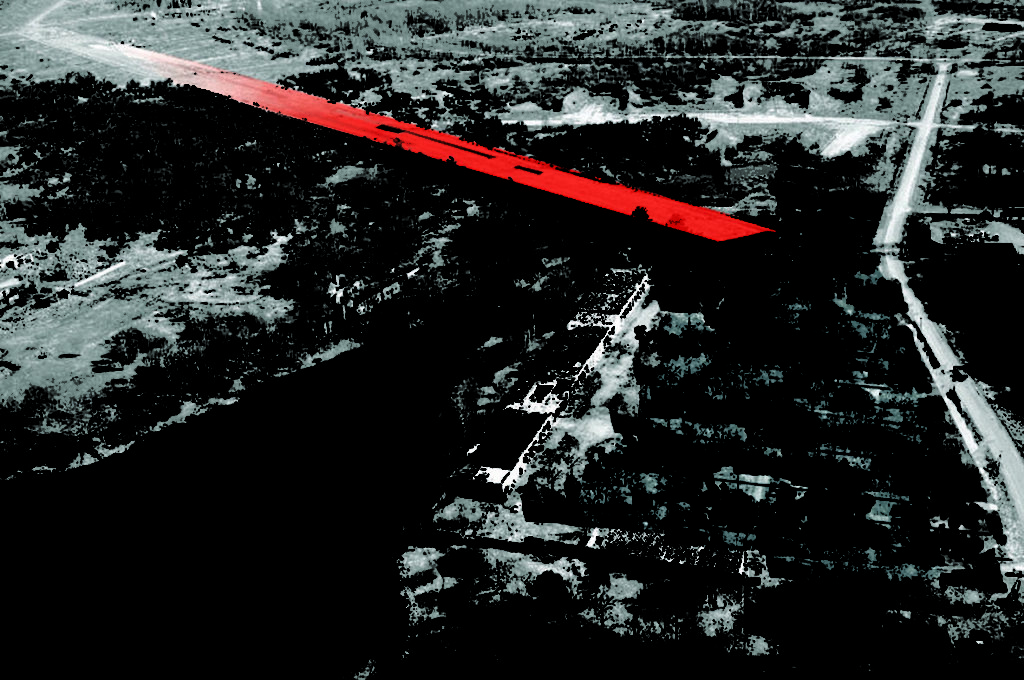

The following text is an attempt to conceptualize the architecture of the new Estonian National Museum building as a process. The focus of the article lies not so much on what the museum’s architecture is as on what it does. The individual user’s experience is not in the spotlight, but rather Estonian history. So, let’s ask ourselves, what does the museum’s architecture do with Estonian history?

Tänasel kujul on Kultuurikatel aga otsekui pommitabamuse saanud. Protsessi käigus on sealt minema pühitud nii ideed kui ka autorid ja valminud hoonest on kärbitud viimanegi avalikku kasutust toetav arhitektuurne struktuurielement. Kultuurikatlast on saanud keerulise logistika ja põhjendamatu ruumiprogrammiga elitaarne A klassi rendipind, mille on kinni maksnud Euroopa ja Tallinna inimesed.

European Union assistance has had a very strong influence on the appearance of Estonian towns, villages and landscapes in the last decade. Much has been done, but the real question is what has been done, and how. At the start of the previous European assistance period, local governments were encouraged to be active in asking for support. Something akin to a mentality became widespread: if money is being handed out, it has to be accepted and spent.

Siiri Vallner is an industrious architect, who is sensitive and attentive towards the environment, while at the same time, her projects are rational and conceptual. Interviewed by Jarmo Kauge.