The general plan for the Põhja-Tallinn city district is headed in the overall direction of diminishing the proportion of industry, increasing openness to the sea, developing the mobility environment via public transportation and bicycle traffic, and strengthening the blue-green network of the district.

The municipality and the developers are in agreement in terms of the visions on how to proceed with Põhja-Tallinn—each wants development, repurposing idle areas, and both parties are actively looking for solutions to enable the development of urban build on the peninsula. This comes with economic requirements and obstacles in urban spatial planning which are being tackled locally by developers on the one hand, and urban planners from a more comprehensive urban viewpoint on the other. How much of development activity is controlled urban planning based on urban spatial visions, and how much of it is a global development trend being implemented by private initiative?

Vision

A long coastline, biodiverse green areas, and industrial architecture heritage make the district one of the most unique and versatile of living environments. Opening to seaside areas is the main potential to be honed by the spatial development. The largest development areas of Põhja-Tallinn are tied to the seashore and the former factory areas of the district, which in the urban visions morph from being closed monofunctional areas to open and versatile environments. Uncompromising, modern architecture will be adjacent to historical factory buildings, new public space and parks will be created, making these areas attractive and accessible to all. Controlled by the general plan, creating dwelling spaces of different types and suitable for different members of society will ideally produce a versatile building stock and alleviate the economic and social segregation of the residents. All development areas will be joined by public transportation and bike lanes, and by the possible extension of commercial train travel to Põhja-Tallinn, the partially restricted peninsula will become a destination for the entire Tallinn region. New central areas will emerge by the sea area and together with the existing community centres, the result will be a contemporary urban space where daily activities and services will be a 15-minute walk away for most residents.

This positive urban build vision is present in the development strategy of Tallinn as well as the general plan of the district. Whether or not the vision becomes a reality and if so, what form it actually assumes in actual space as it comes to fruition step-by-step, we will be able to tell in the future. In the current writing, we are attempting to explain the role and options of the urban architects and planners in directing the development.

Restricted growth

The world is urbanising and globalising, the effects of which are also reaching Estonia. Tallinn is a city with a growing population and the attraction site of the state, therefore, when directing and condensing the city’s spatial development, it is better to focus on the brownfields (former factory and harbour areas), and not the urban suburbs, as this would increase commuting, or the green areas, as that would oppose the principles of sustainable spatial development. Relocation of trading and manufacturing units to places with logistically better access reduces the number of heavy loads in the city district and with that any negative disruptions to the local inhabitants.

Upon compiling the general plan, we have estimably analysed the increase of the working and residential population and found out that upon maximum realisation of the construction rights granted by the general plan, the size of the population will estimably grow by 44,000 people, that is, up to 100,000 residents. An approximately similar increase in the number of jobs is prescribed, as the general plan directs developmental activities towards a more versatile use of the land.

Põhja-Tallinn has a long shoreline. Estonia does not have another city or city district as close to the sea where the link between the built environment and the sea would be so intense. The district features about ten former industrial quarters and harbours, where enriching an architecturally enticing industrial heritage with modern architecture would create fantastic conditions for the formation of unique urban areas and multi-layered dwelling environments. Each brownfield has its own story, heritage, and identity that should be protected by developing place identity that is based on it.

No doubt, doubling population on the peninsula is a great urban build challenge, especially regarding the assurance of accessibility and mobility, but also with regard to the sufficiency of social services and public space as well as maintaining and improving quality of life for the existing residents. The mobility study1 carried out in 2014 already indicated that city district planning and assuring mobility only has two outlooks: to end urban build development by 2024 or to radically change the ways and needs for mobility. The study also revealed that by not modernising the types of mobility, it will only be possible to realise 8% of the construction rights planned in the design without exacerbating the situation.

By relying on the study, doing urban planning and pre-emptive investments, it is possible to avoid setbacks that would otherwise accompany the development. The growth of Põhja-Tallinn is, however, rather firmly limited and these limitations apply to all development areas in the form of restricted housing density, to keep added construction output under control.

Development strategy and various interests

Põhja-Tallinn is known for the highly appraised Kalamaja and the cosy living environment of Pelgulinn that are characterised by low to four-storeyed wooden buildings and private courtyards. Looking at the housing stock of Tallinn as a whole, these types of buildings are the rarest and they are proportionally considerably less prevalent than in other European cities on average. Therefore, our goal is to develop Põhja-Tallinn as a district with low housing stock. According to the developers, however, industrial architectural heritage and lower scale is a restriction that rather increases the price of the development and lessens profitability. Yet, aiding the creation of a strategic human-centred urban space could be considered one of the main roles of a city.

How to find good balance between urban build qualities and economic output is the main topic of concern in all development projects. A 15-minute walk to the city and up to four-storeyed dwelling houses are mentioned in all strategic documents, but how is it achievable so that developers would be content, too? How much conceding is allowed on account of the goals set in the general plan, how much can housing density and the number of floors be increased so that the developer would agree to begin development work? To avoid unfair competition, we have set equal conditions for all developments by region both in terms of height as well as density. In some well-grounded cases single higher edifices are allowed—accents and landmarks. Discussions are being held on topics such as the influence of restricting the number of floors and density on housing availability, whether taller buildings and greater density make housing units more accessible and affordable like some landowners claim, or are these backed by greater development profits? Restrictions are difficult to accept and using urban build argumentation to substantiate the situation often does not suffice.

Mobility

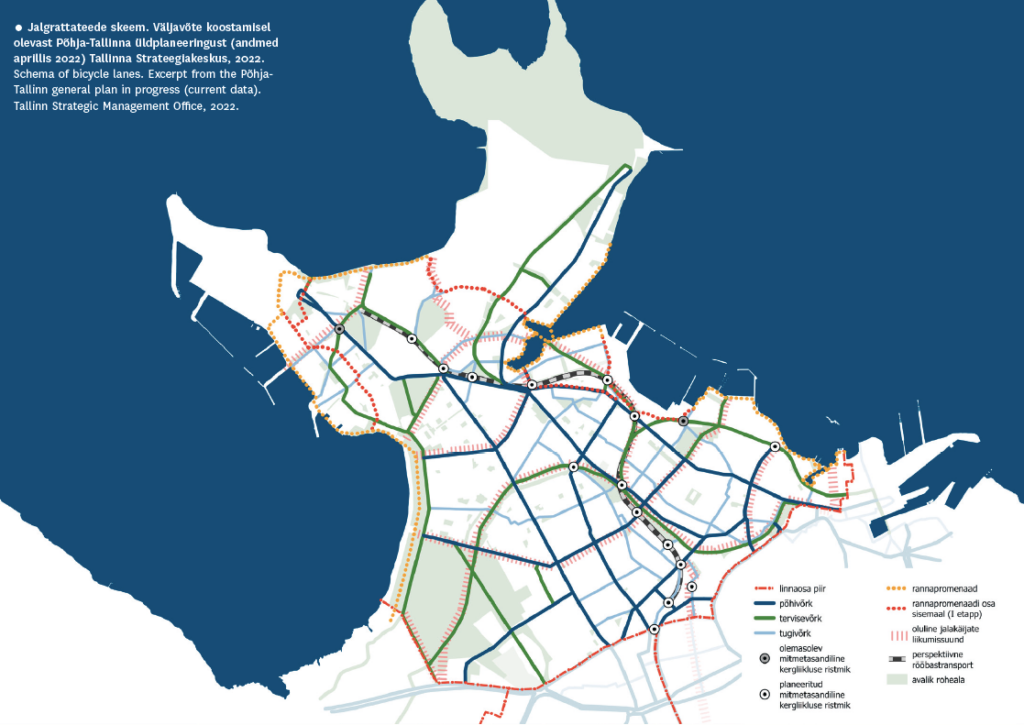

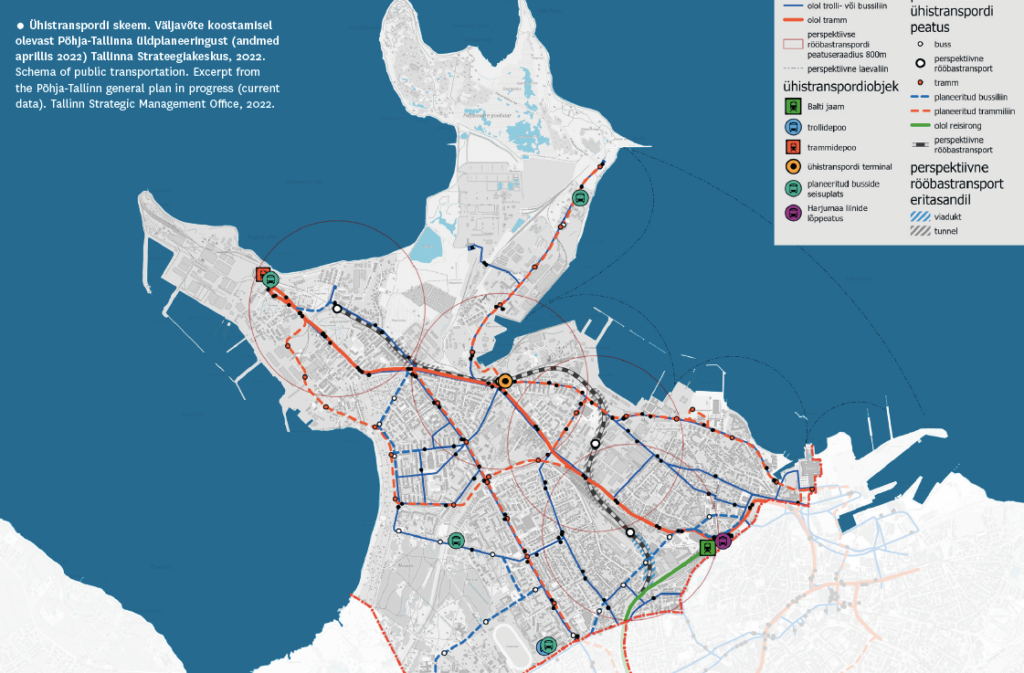

The main bottleneck in the development of Põhja-Tallinn is the street space and public transportation that have expanded and no longer meet the changed mobility requirements. Quality in living and working environments is underlined by recognising the importance of coherence with the rest of the city and its various networks: the public transportation system, human-friendly ways of mobility and streets, green areas, and mobility in the green network. Developing and enabling sustainable types of mobility is one of the priorities in the general plan of the district underway, as these are essential conditions for the proper evolution of a peninsula-shaped part of town.

Tallinn 2035 development strategy and the general plan for Põhja-Tallinn have set a strategic goal to shift 70% of daily commuting to being car-free by 2035. Development of public transportation and bicycle lane networks as well as increase in the user ratios of these mobility types are therefore the most significant parts of a district’s mobility environment. Reconstruction of streets or (in development areas) planning new streets must ensure comfortable footpaths and bike lanes. A district’s versatile mobility environment and the multitude of mobility means has a direct influence on the traffic load of the streets of that part of town. Upgrading the parking policies of the city in conjunction with these changes is extremely important to optimally regulate the number of added cars.

When compiling detail plans, it is the city’s duty to ensure that planning solutions are aimed at orienting all mobility towards the primary use of public transportation and creating a comfortable environment for commuting on foot and by bicycle.

Time horizon

The development potential of a city district is immense, and realisation of the build is a long-term process, considering the general building capacity in Tallinn. Developments should be planned in time-based increments and planners should avoid a district from becoming one big construction site. That has been our goal with the general plan from the perspectives of both mobility and comprehensive environments, by defining the areas that will be developed later on, or by verbalising the preference for areas near downtown and with good public transportation connectivity. How do you tell someone that one development is a priority from an urban build perspective, and another must wait 20 more years before action can be taken?

Dividing one development area into phases based on the completion of public transportation capacity is logical but not without questions raised about how to distribute the development phases throughout the urban space. The phases must, in turn, be based on comprehensive solutions, with room for buffer zones in the transitional areas between the phases, and temporary use should be preferred to activate the urban space—but is all of this enough?

Success has often accompanied developments where the business model is incremental, where building is approached by single houses and urban spaces completed gradually, with a broader vision curating the process. A good example can be made by the Telliskivi and Põhjala quarters where the gradual occupation and alteration of space became a distinct spatial strategy. We must admit that applying this kind of by-piece-development logic renders the classical municipal control- and long-term-based urban planning quite helpless. Often, the municipality lacks courage to make spatial decisions for fear of future accumulation of problems and there is no trust in a self-organising capacity.

With large development areas, compiling complete detail plans essentially means planning spatial development in the very long term, we might even say, the objective is to plan a finite solution in an infinite perspective. However, these hyper-long-term ideal solutions come at the cost of all ‘small spaces’, cool temporary uses and random but significant layers.

Planning diversity

There is somewhat of a chasm between contemporary urban build theories and actual urban planning. The question is often about what the tools are for general plans that would ensure a versatile, human-centred, and multifunctional urban environment. How to create public space, parks and squares in a development area entirely in private ownership, how to preserve jobs requiring low qualifications, small production facilities, and simple pop-up bars amidst new housing stock?

In a general plan, we can surely define the height of the buildings and set restrictions to the number of floors they can have, allow for exceptions based on urban build arguments, define the purpose of land use as green area or mixed housing area, and set restrictions to the ratio of living spaces. Such planning measures, however, are restrictions for developers often not complied with. So-called bullet-proof substantiation of criteria that is that specific and based on development areas is generally not possible, which is why general plans call for definition of generalised principles stemming from a broader analysis of the region.

Planning the lead function of a mixed housing area alone will not create a strong foundation for the formation of a multifunctional urban space, because even if the goal is to create a ‘cocktail’ of various building types and functionalities, this type of land use enables all kinds of housing while not excluding anything in particular, either. The specific functions and building types are up to the developer to determine.

In some cases, planning monofunctional urban tissue is justified. An example of this is entertainment and leisure entrepreneurship, which can only be ensured 24/7 in business districts with no permanent residents where the socio-cultural part of the city can exist without interruptions.

Architectural and construction clauses are significant, but the city can only apply those depending on public interest and with clear substantiation from an urban build perspective. For example, it is possible to set urban build requirements on facades adjacent to the streets and the first floors of business centres, aiming at enabling private entrances and showcasing windows for business spaces.

Conclusion

Directing a city’s development must be grounded in an urban build vision and to implement it there must be a societal agreement. In addition to quality factors and the spatio-architectural control of the living environment, it should also contain a vision of mobility and accessibility, public service, social and technical infrastructure, as well as purpose of use for buildings and public space. In the long run, this type of city should also be doable, that is, profitable for the developers and attractive to the buyers. But every development also needs to be useful and not detrimental to the city as a whole, in both a direct economic sense as well as in fulfilling of strategic goals. Finding agreement in such a comprehensive vision is not easy and is rather quite impossible without compromise. Põhja-Tallinn distinctly features these various interests and reaching compromise takes time. Envisioning the former industrial areas in a debate between the developer and the city is missing the balancing role of public interest since these areas do not yet have residential population.

In a legal sense, planning and formulating a city’s development is a hierarchical system, where strategic documents and general plans provide the general principles for urban building, detail plans provide the spatial solutions and building rates for quarters or lots, and a construction project the architectural solution for a concrete building. And to the policymakers, everything seems to be in order. In reality, a hierarchical system like that does not ensure the generation of a high-quality living environment even if all the phases are passed at the highest possible level. The reason lies in the inevitably high level of generalisation in the strategic and planning documents, which do not automatically define the quality of urban space on specific lots. The objectives and quality requirements of strategies and general plans do not translate directly to the detail plans and projects but require constant interpretation to specific locations and sites. To create high-quality space, it is necessary that the architect of the local government be continually diligent in directing the spatial development of the area (throughout all phases of planning and design)—and curate the development of the urban build prudently. Quality and uniqueness in urban space are, after all, created by architects and developers.

JAAK-ADAM LOOVEER, ANNA SEMJONOVA ja MIHKEL KÕRVITS Jaak-Adam Looveer, Anna Semjonova, and Mihkel Kõrvits are urban planners at the Competence Centre for Spatial Design at the Tallinn Strategic Management Office, and authors of the general plan for the Põhja-Tallinn city district.

HEADER photo by Kaupo Kalda

PUBLISHED: Maja 108 (spring 2022) with main topic Opening Tallinn to the Sea

1 Osaühing Stratum, „Põhja-Tallinna liikuvusuuring 2014“ [transl. ‘Mobility Study at Põhja-Tallinn’], 2014, https://uuringud.tallinn.ee/uuring/vaata/2014/Pohja-Tallinna-liikuvusuuring-2014.