ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND THEATRE LARGE HALL

Interior architecture: Aivar Oja / FRA Disain

Architectural acoustics: Linda Madalik

Architecture: Toivo Tammik, Mart Rõuk / Ansambel

Client: Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre

Client project manager: Ott Maaten

Contractor: Nordlin OÜ

Net area: 528 m2 (Large Hall), 6140 m2

(extension total)

Project: 2012–2016

Construction: 2019

Happiness—a word frequently used to describe the sensation emanating, exuding and radiating from the newly completed large concert hall of the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre. How is happiness built?

Awakening. Acknowledging

A student of music may well consider a musical instrument to be an extension of herself. In fact, the connection to one’s instrument may prove to be more intimate than any human relationship. An intricate, web woven of feeling, sensation and cellular memory begins to form from the very first moment we place our finger or lips or foot on our partner—our instrument. A delicate formation process gathers momentum and fluidity with daily practice embedding into our nervous system this device that was not quite attached to us (or in the case of singers, developed) at birth as seamlessly as it were our private heart or lungs. A near supracorporeal morphosis like this surely demands the right conditions from its environment, which are now comfortably provided by the new concert hall of the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre. The magical capability of architecture is to create solutions, enable access, raise potential, and unfold us, humans.

Architects Toivo Tammik and Mart Rõuk from the Ansambel architectural consultancy, who designed the extension, approached the ambitious necessity of accommodating within the new volume both the studyrooms as well as the publicly accessible large concert hall and blackbox, and linking it all with the existing building, based on the principle of contrast. The horizontal, elongated and light-coloured space, full of sounds from several generations, was extended by a rhythmically playful, visually distinct architectonic shape that still harmonises with the surrounding cityscape. According to the architect’s descriptions, performing the task of conjoining the old and the new at a level of technical excellence was, in architectural terms, nothing shy of a heart transplant. The level of intricacy involved in establishing a connection with the external urban environment is revealed when walking around in the building, and from one floor to the next. Fantastic views of the sky and cityscape open at unexpected places!

Observing the sky is an expected activity one might imagine happening in a unique and intimate quasi-outdoor space which is both open to the sky, and situated between two large, temporally distinct built spatial volumes. The essential function of the study building that has existed in a dispersed or even abstract form up until now, i.e., the core of the interior of the extension, the large concert hall, was intriguingly emphasised by skilful use of lighting in the original design, leaving it visible from the outside on Sakala Street and discernible as the most important part of the entire complex. Being a school building, the idea of such a solution prompted in me an image of a bare, featherless, tiny bird with blood vessels and closed eyes still underpinning its translucent skin; an acknowledgment that through architecture it is possible to be in primary contact with developing organisms who are susceptible to external impulses; and perhaps a question as to whether or not architecture can create trust and stimulate in us all a heightened sensitivity, and ultimately uncover our life force and full potential?

Flesh of the woods

Ethnographer Art Leete has thoroughly researched and written about the Komis, a people who live in the forests of the tundra and taiga, their creation myths and their relationship to nature and acts of creation. The article, published in Vikerkaar , is a worthwhile read, especially in connection with the new concert hall of the EAMT, as the light rosy (‘birch-core-white’ according to the interior architect since the wood veneer was cut from the core of the trunk) wavy panels are directly related to these animated Komi forests. This fascinating piece describes mythical beliefs according to which a person must be experienced or willing to experience processes in the evolution of her awareness that are potentially exposing, in order to be able to understand the fundamental structures underneath the relationships between the creator and creation. Deception (or self-deception), acquisition of power by illusory means, abuse of benevolence are if tools that lay the groundwork for experiential knowledge gain which in the best case scenario leads to the birth of a master whose mind governs over living nature.

The ultimate human form amongst the Komis is the hunter whose success in navigating through the thickness of his own forest is dependent on how well he is able to balance between the seen and unseen, the manifest and unmanifest. It is rare that the language he uses takes the form of a word. In a like manner, a person who is only just getting to know herself may not know where the path she treads might lead. Her goal is to master her instrument and become fluent in a non-verbal language so that she may express her creative will. The air and flow essential for music-making can be too easily interrupted by in a linear way expressing a note that is transcendent by nature. Similarly, the Komi truth may at the base level seem a pure falsehood, a half-truth or simply incoherent. This is so because for a Komi being too direct will destroy the fine network between two quintessential polarities, causing him to lose power and command over animals, plants and all of nature. Candour, a concept generally synonymous with the value of honesty, and figuratively the sun that sheds its light on darkness, is for a Komi a clogging of the vein of life, a calling on of self-destruction that terminates the hunter’s luck and causes the forest to shut its doors from him. The material of the concert hall that acoustician Linda Madalik and interior architect Aivar Oja worked with came from these very forests. Could that mythical insight have carried over from the birch trunks to the blueprint of the concert hall?

Linda Madalik has designed the sound fields of many of the most prominent buildings in Estonia. Sound is a mechanical impulse that humans have learned to use for purposes of supporting as well as destroying life. Not only our auditory but also our non-auditory cells are receptive to the effects of sound. This is not all that surprising as after birth our evolution continued in the forest. We are adapted and attuned to communicate with trees, plants and animals. It is merely the language we have forgotten, or perhaps simply awareness of the fact that this language exists in us as naturally as our ability to allow our lungs to breathe or our hearts to beat. An acoustician’s vocabulary is equipped with somewhat unusual phrases such as ‘narrow sound image’ or ‘apparent source width’. A need to comprehend two sensory modalities, seeing and hearing simultaneously, through linguistic code already creates a shift in purely semantic terms. But the language of acoustics also accommodates room geometry, angles and tilts of sidewalls, floor areas and ceilings, and material properties are not the least of its considerations. Command of this language is a prerequisite for collaboration between the acoustician and interior architect, calling forth a sound field that has influence on our health and our aesthetic sense alike.

Branch of science

Environment and architecture have the ability to concentrate and carry knowledge in both explicit and implicit form. The Japanese philosopher Kitaro Nishida coined the concept of ‘Ba’ which signifies a context harbouring meaning. ‘Ba’ has been adopted in knowledge creation models and it has been interpreted as a shared space, enabling generation of new relationships and connections. This space may be physical, virtual or mental. The essence of ‘Ba’ is thus a creative, innovative and tolerant space, creating connection at an individual as well as cultural level. Architecture as the focal point for very different types of knowledge is one of many fields where ‘Ba’ may express and manifest.

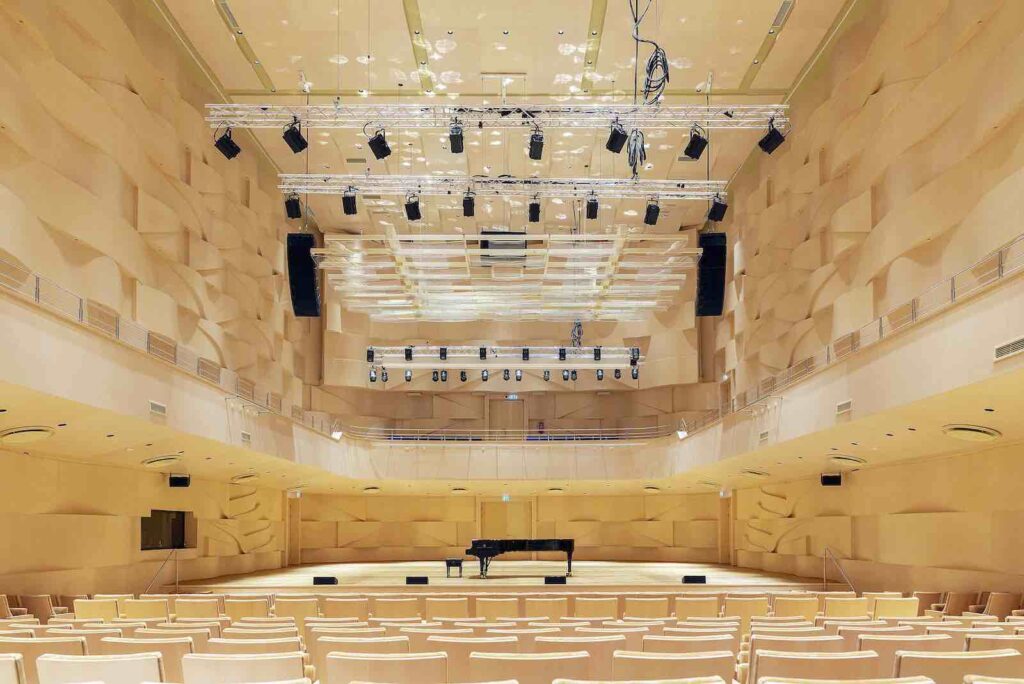

This is why the new large hall of the EAMT is much more than just a convenient rehearsal space. It is an environment for evolving human beings, whose attitudes and intuition are fostered in a space that caters precisely to those inner faculties. Acoustics is the portal through which the ‘code’ of the hall is infused with the wisdom of sensory preferences. The Japanese acoustician Yoichi Ando refers to preferences as an organism’s primary reactions to external stimuli, steering the behaviour and decisions of the organism in the direction of maintaining life, i.e. creativity, a value of knowledge that is capable of integrating with culture. Collaboration between the interior architect and acoustician points towards exceptional success: The hall is an elegant fusion of an introspective intuition and the tacit knowledge embedded in the original material, carried by a physical, mathematically definable, acoustically measurable space. Be it sound waves or gusts of wind shaping sand dunes, interior architect Aivar Oja has sensitively expressed the flow of growth, codifying quiet, steadfast change and transformation in the sculptural landscape of the hall. The tonality of the entire hall (light rosy-white thick birchwood, light-soft seats) creates a feeling of being inside delicate skin. Embedded in it are conditions for an experience that the human mind and body clearly perceive as bliss. Should this not be the focal concern and goal of architecture?

Sound carried by silence

A transparent ‘cloud’ hovers above the orchestra. A mobile, morphing, clear, multifunctional cloud that helps to set the acoustic atmosphere according to the performers and the music programme. On the ceiling above it, for those who can hold their gaze long enough, there are gleaming constellations that neither yet have a name, a definable shape or form…

The hall, which is scaled to the needs of a chamber orchestra, will require adaptation from an orchestra or choir who have grown accustomed to the conditions of a large concert hall. Linda Madalik, an acoustician who, depending on the situation, is equipped with either a pistol, or sound-image-language (often carrying both like a Komi hunter) shares a work-related memory of how once during rehearsal the initial self-expression of the Estonian male choir was so forceful that everyone at once became startled. The response of this dignified lady to that event was to say that the hall truly comes to life through piano…

MARIANNE JÕGI is a graduate of Georg Ots Music School where she majored in music theory. She has an MA in sculpture and installation from the Estonian Academy of Arts. Her postgraduate research and practice involve investigations at the intersection of architectural acoustics and art, with the aim of integrating sensory environmental technologies and spatial form.

Comment

LINDA MADALIK, acoustician

“The way I understand the new EAMT hall phenomenon is that it can act as intermediary for a musical composition in a most profound way.”

We began engineering the EAMT concert hall right after the opening of the first phase of the school building in 1999. With architect Kalvi Voolaid I determined the overall dimensions and room geometry of the hall, which in principle remained the same despite the fact that designing the hall stopped for many years and was later continued by the Ansambel architecture consultancy.

The main dimensions of the hall were: length 33 m, width 16 m, height 14 m. The specific volume, i.e. cubature per person was selected around 10 m3/person, which allows a subsequent reverberation time 2 s, which is appropriate for a concert hall. Matching room geometry and specific volume is extremely important in the design of a concert hall. Once these are set in place, the interior architect does not need to start fixing spatial geometry but can focus on designing the interior.

Interior architect Aivar Oja and I shared a vision of a room made of light-coloured timber with curved surface forms. My intent as an acoustician was to achieve the propagation of sound waves and a scattering of the sound field, while interior architect Aivar Oja worked on molding the wavy and dynamic surfaces. There is an area near the stage where the surface waves break, and this changes the rhythm of the waves.

The main concern in acoustics was how to build a hall entirely with a wooden finish that would transmit all the sound frequencies as evenly as possible. As is well known, wooden panels resonate in the lower frequency range, causing subsequent reverberation time in such rooms to drop in these frequencies. It is appropriate for speech auditoria but ends up being a drawback for larger concert halls with natural acoustics, preventing a ‘mellow and full’ sound image and ‘warm’ sound timbre, to use subjective judgement criteria as musicians do. We strove to overcome this deficit by using thick and rigid wooden panels. That said, the wall panels are 40 mm thick and directly attached to the stone wall. The 25-mm-thick ceiling panels have fixed support to a sound-isolating drywall suspended ceiling. Even the hardened wooden panels resonate to some degree, the panels in the stage zone are filled with wool to disperse these resonant frequencies. The wavy veneer panels were manufactured by wood furniture company Supra Furniture of Sõmeru, who used tight birchwood originating from the Komi tundra regions.

The acoustics of the hall design were computer-analysed by the well-known Danish acoustician Anders Christian Gade, who strongly urged us to create sample panels before construction and test them in laboratory conditions. This enabled us to test the sound absorption properties of the panels which had been a hypothetical selection in the project design since there had been no previous tests done on similar products. Testing revealed that we had done well in choosing the technical solution for the panels and this meant we did not need to alter the project. Despite this, I was in for a shock when I visited the Latvian R&D acoustics lab where the panel testing had taken place. It became evident that even on an entirely flat lab room floor, it was difficult to fit the panel modules together without joints. These joints caused an additional unhinged sound absorption scenario that could have potentially influenced the sound field of the hall considerably. The joints became the key concern for the acoustics. During construction it became evident that in addition to being compressed, all the joints also needed to be filled with silicone.

There are several objective parameters in diagnosing the acoustics of a concert hall which can be planned for during the design phase. These objective physical parameters are met by subjective parameters that describe the sensations of musicians and listeners upon music-making and the listening experience. For example, room subsequent reverberation time, which is one of the main parameters of a hall, characterises the sonority of the room; it also impacts on loudness. How the duration of subsequent reverberation time changes in different frequency ranges determines the timbre properties of the sound. The spaciousness of sound is primarily dependent on room geometry, whereas a narrower room ensures greater spaciousness. A diffuse or scattered sound field will make the listener feel as if they are surrounded by or enveloped in sound. Another important parameter, sound clarity, is also mainly dependent on room geometry. All these parameters had to be addressed for optimal value during the design phase of the hall’s acoustics. It is also important to differentiate between acoustic conditions in the listener area and the performing area. This hall features an acoustic ‘cloud’ (reflector array) above the stage which consists of sound-reflecting transparent plexiglass screens. The screen modules, that have been slightly bent to achieve a curved surface, have been positioned at specific distance from each other, i.e. about 50% of the surface is made of openings. The different parts of this ‘cloud’ can be moved up and down and the entire cloud can be suspended high up under the ceiling for events that use sound amplification. The effect of the cloud at different heights on the performers on stage was tested by RAM, the Estonian male choir. They found that the cloud supports performance conditions considerably and the effect was also audible from the listening area in the hall. The optimal cloud height for the choir turned out to be 8 m which was the normal cloud suspension height in the project as well.

After opening, Aivar Oja and I listened to numerous concerts in the hall and exchanged our listening experience. Each performance revealed the hall from different acoustic aspects, but it was during the Zurich Youth Orchestra’s concert performance that I completely lost myself in listening. I experienced a metamorphosis… all at once, the hall around me with its interior design and everything else including the people disappeared and I had transformed into a special state of awareness. Around me and inside me there was only music, very intense music. And since there was nothing else—no room, no objects or subjects—the music managed to find its way to a very deep space of my consciousness. A place of whose existence I had not been aware of until then. It is the place where deep happiness comes from.

PHOTOS: Paco Ulman.

PUBLISHED: Maja 101-102 (summer-autumn 2020) Interior Design.

1 Leete, Art. The sacred woods of the Komis. Vikerkaar, October, 2016.

2 Selected prominent works: Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre school building phases 1 and 2, Pärnu Concert Hall, Jõhvi Concert Hall, St John’s Church in St Petersburg, renovation of ‘Estonia’ opera theatre, Estonian National Museum, reconstruction of ‘Kosmos’ cinema, Tallinn City Theatre, Tondiraba Ice Hall, reconstruction of Theatre NO99 foyer into jazz club.

3 A reflector array over the stage