Concrete stuff

Architects and engineers are taken with concrete—a material without a natural form of its own, meaning that it can be shaped precisely to one’s intent, according to physical forces. Its production can be easily repeated, accelerated, globally scaled; its monolithic, uniformly continuous mass resembles man-made stone. In the Estonian language, this has resulted in a deviant categorisation—houses built from aerated concrete blocks are classified as stone buildings, even though such blocks do not occur naturally in the Earth’s crust. Scientists are not unanimous on whether we have already reached the Anthropocene—the geological epoch in which the Earth’s crust is most affected by human activity—but the triumph of concrete sets an example of the planetary impact of our species. Take, for instance, the world’s largest hydro electric power plant, the Three Gorges Dam. The enormous structure holds back 40 billion cubic metres of water, which allegedly slows the Earth’s daily rotation by 0.06 microseconds due to its weight.

Concrete’s strength is not only physical, but also political.

Concrete has become synonymous with development. It implies a lot of building and building at scale; it comes with the potential of growing the local economy, creating jobs, improving accessibility, and providing new energy infrastructure. This is what makes the country’s GDP and international competitiveness grow—thus, concrete’s strength is not only physical, but also political. Megaprojects such as dams, highways, data centres, and shopping malls improve the well-being of selected groups of people and soften the impacts of a volatile economy. But are these objects always necessary? Geographer David Harvey refers to such megastructures with the term ‘spatial fixes’. Spatial fixes are objects that result from redirecting surplus capital within a free-market economy into physical space, with the aim of preserving or increasing capital value. Pouring concrete boosts the economy; furthermore, one can always find some spatial issue or other to solve with it. However, Harvey notes that these solutions are unevenly distributed in time and space, and such temporary bursts generate further problems of their own that then need to be addressed. One example of this is our local ‘Euroarchitecture’.1 As Merle Karro-Kalberg pointed out in 2007, no one was really keeping tabs on all the overpasses and concrete sidewalks that were being built. All available funds were simply put to use. Now we have to deal with urban sprawl, car-centric planning, and underground car parks that account for 30–50% of a building’s carbon footprint. Harvey urges us to view concrete not only as a physical body, but in a more abstract way—i.e., not only as a material or an object, but also as a social process.

Imagine a flat hilltop—level, dry, and firm footing. Concrete stuff. This seemingly spontaneous plateau has enabled a certain part of the human species to have stable growth of wealth and well-being, improved health and hygiene, and global interconnections. The plateau keeps expanding to serve the needs of a growing digital world as well. The development of ever more powerful AI models goes hand in hand with the pouring of ever more concrete. Emissions from building Microsoft’s new data centres increased by a third last year compared to 2020. Yet, the pressure that this growth puts on everything around the plateau—on those who are not living on it, on other species, on natural resources, and on the planet as a whole—is increasingly evident. Although dictionaries define the term ‘plateau’ as a stable, fluctuation-free state, they also include a caveat: it only lasts for a certain period of time. So, what comes next?

New objectives

One measurable common goal that has been set to limit the harmful impacts of the expanding plateau is to reduce carbon emissions. The most energy-intensive part of concrete production is clinker production. Thus, alternative clinker types with a smaller carbon footprint are being developed all around the world and used in products such as Celitement, C-Crete, Solidia, EcoCrete, etc. But even if new binders are developed and concrete producers are able to find better ways for utilising or capturing carbon, it is unlikely that the emissions from global concrete production will decrease. It is more likely that the exact opposite happens, due to the Jevons paradox—the more efficiently a resource is used, the more of it is consumed.2 Business as usual, the spatial fixing of capital, will continue without any significant shake-ups.

The alternative is to dismantle that very same reinforced concrete plateau in order to create new buildings from it. This is not only a technological challenge, but requires a deep intervention in the machinery of the current capitalist and extractivist system. Reuse of (concrete) materials stands in complex relations with the standardised, automatised, exponential, globalised concrete production, which is bringing economic benefits to an ever smaller group of people. Circular materials are so uneven and varied that they tend to push us back towards handcrafting, where each element needs to be sourced from existing local buildings, measured, cut, and certified separately. Still, this process also hints towards a possible new paradigm. The society should invent and employ new collaborative practices that would enable a more local and cohesive construction sector than monopolistic mass production does. The default should not be movement towards a monolithic, but rather a heterogeneous world.

We could also set the measurable goal of extending the lifespan of concrete buildings. While trees sequester carbon as they grow in the forest, concrete does the same for many years after the building has been built, through a slow process of carbonation. Extending the lifespan of buildings is not only about speculative computational models, but rather about broad social and legal agreement to preserve existing buildings, and ultimately about architecture responsive to such changes. Thus, taking longevity as a metric follows Harvey’s call to understand concrete’s relations to complex social processes.

Structure

Constructing buildings with a truly long lifespan of more than 50 years while following reuse principles seems to clash with the very logic of the capitalist economy, as it reduces the demand for new materials and buildings. Still, could there be ways to promote this approach? In 1997, architects Marika Lõoke and Jüri Okas received the annual architecture award from the Cultural Endowment of Estonia for designing the new Forekspank building at Narva Street 11 in Tallinn. The project utilised an existing concrete frame of a former industrial building. Back then, this was the cheaper and more efficient solution. Today, it is generally cheaper to build from scratch, which is why additional incentives are often sought from the municipalities and the state. In Brussels, during the tenure of regional chief architect Kristiaan Borret, a local law3 was adopted stating that buildings must be retained and preserved, and can only be demolished if the new building demonstrably improves the local quality of life or the environment, as well as passes the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). At the Estonian Centre for Architecture’s Circular Architecture Accelerator seminar in Tallinn,4 Borrett presented projects in which he had the mandate to commission alternative analyses and spatial proposals from select architectural offices with the aim of preserving certain buildings—proposals that could fundamentally contradict the developer’s plans to demolish them. This sort of approach is not meant to restrict new developments, but rather to prioritise housing accessibility, reduce forced relocations, and value existing communities. One can only dream that a similar mandate will also be given to the state architect of Estonia. In any case, it provides a direct means to influence the architect’s field of work, allowing them to focus on reusing existing buildings and the ubiquitous concrete load-bearing structures.

ANKRU 8

Type: apartment building

Location: Tallinn, Estonia

Architects: Molumba (Karli Luik, Johan Tali, Harry Klaar, Heidi Urb)

Interior architects: Pink (Aet Grigorjev), Kadi Laur

Landscape architecture: KINO

Client: Ankru 8

Contractor: Hausers

Structural engineers: Ehitusekspertiisibüroo (Siim Randmäe, Kaspar Karus)

Completed: 2024

Area: 5408 m2

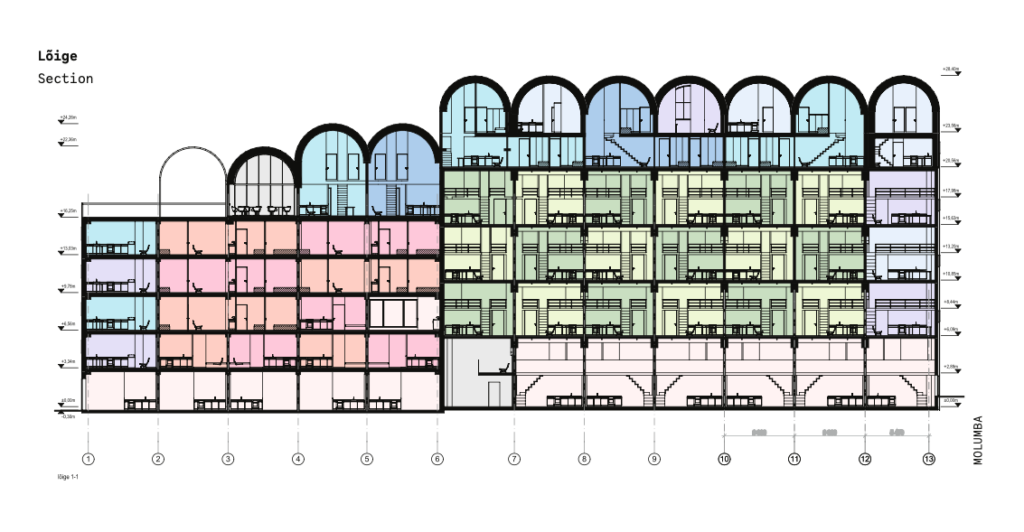

In 2024, Molumba Architects received annual architecture awards from both the Estonian Association of Architects and the Cultural Endowment of Estonia for converting the former factory at Bekker Port, Ankru Street 8 in Tallinn, into an apartment building. The requirement to preserve the existing concrete frame was written into the brief by the developer Hausers for practical considerations—this enabled to avoid pouring new foundations and structures, start the construction works earlier, obtain the necessary permits more easily (since it was categorised as an extension rather than a new development), and get a market advantage from the resulting rough industrial look.

According to architect Johan Tali, the uneven floors, irregular column spacing, and varying ceiling heights of the existing concrete frame presented quite a challenge. A further half-floor was added between the 4.5-metre lofts, with a floor to ceiling height of about two metres. ‘Legally speaking, these are auxiliary rooms and do not form a part of the saleable area. But buyers understand that they could be just as well used for, say, bedrooms,’ says Tali. Regarding the Estonian context, he highlights how engineers are often hesitant to work with old concrete floor slabs, since they lack personal experience with old-time construction practices, doubt their competence, and fear taking risks. ‘That’s when you need to find yourself an old-school type—someone with a pencil still behind their ear, someone who will tell you stories from the Soviet period when bicycle frames were used as rebar,’ adds Tali.

and a spacious roof terrace with a greenhouse.

Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Ankru Street in Tallinn into an apartment building.

Photo: Johan Tali

The important realisation here is that having a good skeleton is a must. Existing concrete frames in Estonia often have poor construction quality, and the difficulty lies not only in finding engineers and contractors but also in convincing the clients that this sort of structure is worth exhibiting and its robustness is something to be appreciated. Moreover, there is a lack of regulations that would support their preservation and a lack of requirements to reduce the carbon footprint. Pouring new concrete gives ‘a kind of solid feeling’—to engineers, private clients, as well as the public sector. ‘Green talk won’t get you far in Estonia. By the pre-construction design stage, environmentally conscious ideas in the initial brief tend to be forgotten,‘ says Tali critically of the reigning mentality, and contrasts it with exemplary experiences with international clients as well as Finnish building practices, where environmental awareness and sustainability are genuine guiding principles rather than mere lip service.

Photo: Hampus Berndtson

THORAVEJ 29

Type: office space and community hub

Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

Architects: Pihlmann Architects

Interior consultant: Sara Martinsen

Client: The Bikuben Foundation

Contractor: Hoffmann A/S

Structural engineers: ABC Consulting Engineers

Completed: 2025

Area: 6224 m2

This year, a reconstruction project designed by Pihlmann Architects was completed at Thoravej 29 in Copenhagen. Originally built in the 1960s as an office building, it now houses the philanthropic foundation Bikuben (Bikubenfonden) as well as innovative social and artistic start-ups.

The concrete columns, ceilings and floors are exposed in their robustness, and a spatial gesture is made with slanted concrete TT floor panels supporting the staircase, making the new foyer feel more spacious and allowing natural light to pass through the building. The idea, which appears simple at first, required extremely precise execution. For example, during the cutting and lowering of the floor plate, it was necessary to maintain the internal tension of its reinforcement so that the plate would not collapse under its own weight. The construction process involved 3D scanning of structural elements, custom furniture design, meticulous planning for on-site material storage, and making sure that the roof stays in place during the large-scale works.

Photos: Hampus Berndtson

Johan Tali visited the object in early June as part of an educational trip organised by the Estonian Centre for Architecture’s Circular Architecture Accelerator. ‘It is a total work where everything is on display. Even the new ventilation ducts are part of the spatial experience and align with the ceilings instead of following the shortest possible trajectory.’ The ventilation system is located on the rear façade, newly built primarily from steel and clad in glass. The same principle of delicate materiality was observed with internal partitions in order to highlight what was preserved. Reportedly, 95% of the materials in the project are reused. Tali says that visiting the building felt like being in a house museum where the display and the contents are closely intertwined. ‘It is not technically impossible to do something like that in Estonia, but it just doesn’t fit the budgets,’ says Tali.

Indeed, paradigm-shifting projects tend to be expensive and are therefore often stigmatised. But if the public sector can update regulations, the wealthy private sector should be progressive with building practices. Here, the architect’s role is far from passive—on the contrary, it is to actively seek and introduce clever solutions that go beyond mere façade decoration.

Bricoleur

Perhaps the modern architect needs to be a bricoleur. The concept was coined by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in the last century. A bricoleur is someone who is using trial and error to fit limited available materials to a new purpose for which they were not originally designed. Lévi-Strauss was not talking about creative work per se, but more broadly a mindset that enables one to find new solutions depending on the particulars of each situation. To be a bricoleur is to work in diverse ways, notice opportunities for collaboration between people, materials, and other species, and stand in a tangible relationship with the environment and society. However, the work of a bricoleur-architect requires support from similarly minded engineers, planners, private and public sector clients, and contractors, who are likewise interested in rethinking their roles in a changing world. The concrete plateau is not a neutral ground any more. On it, social, political, and ecological responsibilities should be carefully scrutinised.

ROLAND REEMAA is an architect at LLRRLLRR and an assistant professor at the Estonian Academy of Arts and the University of the Arts London

HEADER: Nikolai Kormašov, Raudbetoon (Reinforced Concrete in Estonian), 1965, Estonian Art Museum

PUBLISHED: MAJA 2-2025 (120) with main topic CONCRETE

1 Merle Karro-Kalberg, ‘Euroarchitecture’, Maja 89–90 (2017)

2 A paradox put forth by English economist William Stanley Jevons in the 19th century during the Industrial Revolution, a period of intense coal min

3 See the book The Architecture of Reuse in Brussels (p. 6) and the 4th article of the regional urban planning regulation (RUPR).

4 Public seminar ‘Present(ing) Resources’ on 9 May at Erinevate Tubade Klubi, organised by the Circular Architecture Accelerator.

5 Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (University of Chicago Press, 1962).