Roland Reemaa interviews Eva Gusel, one of the authors of the project +/– 1 °C: In Search of Well- Tempered Architecture, that represented Slovenia at the 18th International Architecture Exhibiton in Venice.

When the effects of resource overconsumption begin to hit energy bills, debates on building heating and cooling become heated. Striving towards energy efficiency is now an undisputed demand of users and clients. It is codified in laws and regulations, worked out by engineers, and integrated into designs by architects.

Casting doubt on this chain of actions, Slovenian architectural offices Mertelj Vrabič Arhitekti and Vidic Grohar Arhitekti had long pondered on the relationship between the strive for efficiency and the prevailing concepts of sustainability and ecology. In 2023, after winning the open call in the previous year, they presented their critical explorations as the Slovenian pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, with an eloquently titled project +/– 1 °C: In Search of Well-Tempered Architecture. It is an attempt to bring ecological and thermal comfort issues back to the domain of architecture and discuss them through building design.

Photo: Maxime Delvaux

The pavilion and the accompanying publication were praised for their subtle design and clear messaging. By looking into vernacular techniques across Europe, the project invited architects to reconsider their reliance on standardisation and technology in achieving thermally comfortable spaces. History is to be learned from but can also turn into a retreat to nostalgia. I discussed with one of the project’s authors Eva Gusel why we should search for thermal comfort in the past and what it means for today.

Roland Reemaa (RR): Although I only heard positive things about your pavilion design in Venice, I would like to focus our conversation on the publication that followed. It presents historical vernacular examples from all around Europe with a particular focus on how energy consumption, building design, and activities, i.e. people’s ways of life, were inextricably intertwined in the pre-modern era. What was the starting point for your research, and how did you organise it?

Eva Gusel (EG): We started our research in the first year of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. Winter was approaching, and the dependency on Russian gas became a major debate in Slovenia and the rest of Europe. This concern made the project immediately relevant.

There are many ways to study the past—for example, through material and construction techniques or community involvement. We wanted to look at the past through the lens of energy efficiency. We focused on Europe because of its diverse climatic environments, ranging from harsh winters to hot summers, from seas to mountains. Europe also has a long tradition of researching its vernacular architecture. This gave us the opportunity to reach out to friends and colleagues from the field and ask them to share their examples, which became the basis for the catalogue and the exhibition.

Photo: Maxime Delvaux

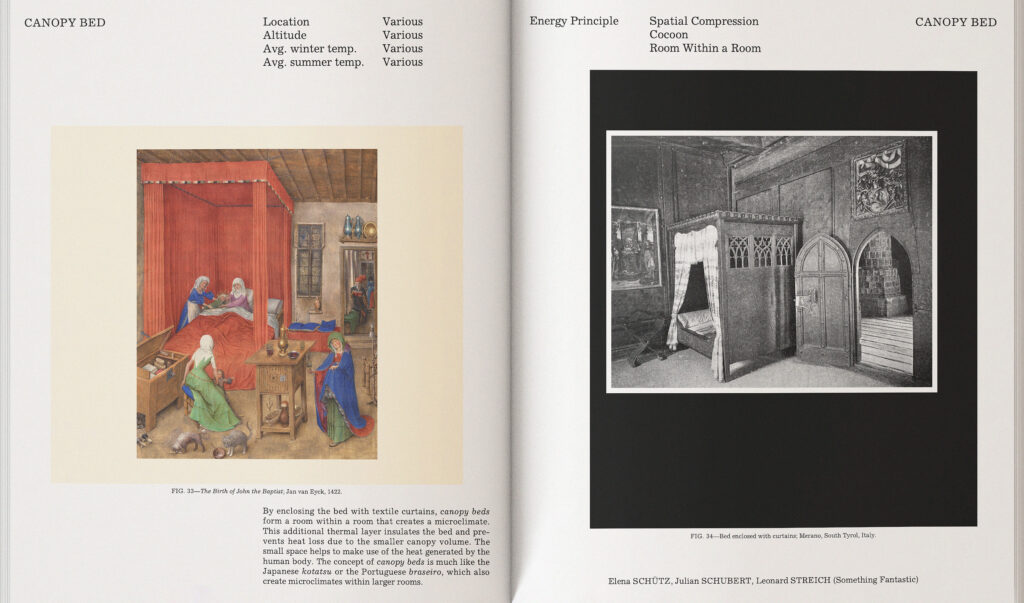

RR: The catalogue consists of 50 examples from around Europe that present a wide range of architectural elements, from blankets and beds in the interiors to spatial layouts and foliage-covered façades. How do you suggest the reader should consider these examples in the contemporary context?

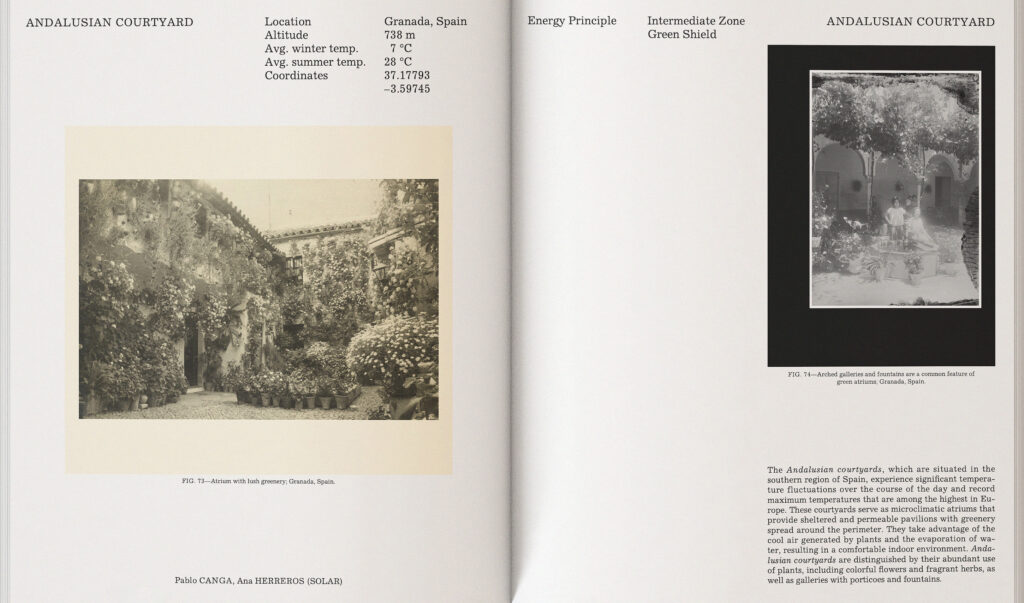

EG: We worked collectively with our colleagues from across Europe who sent practical contributions. In the end, we formulated these techniques into 13 energy principles, such as Room Within a Room, Seasonal Living and Fat Wall. They should be understood as abstractions of dealing with energy in buildings. Today, some of these concepts can be applied directly, others indirectly. For example, one of the most practical principles is urban greenery, where trees and plants are an integral part of planning and designing comfortable places. They should not only be considered as decorative features—they create microclimates in cities. Another directly applicable idea when designing today is the overall idea of seasonality—the principle of temperature zoning.

RR: How did you define vernacular architecture?

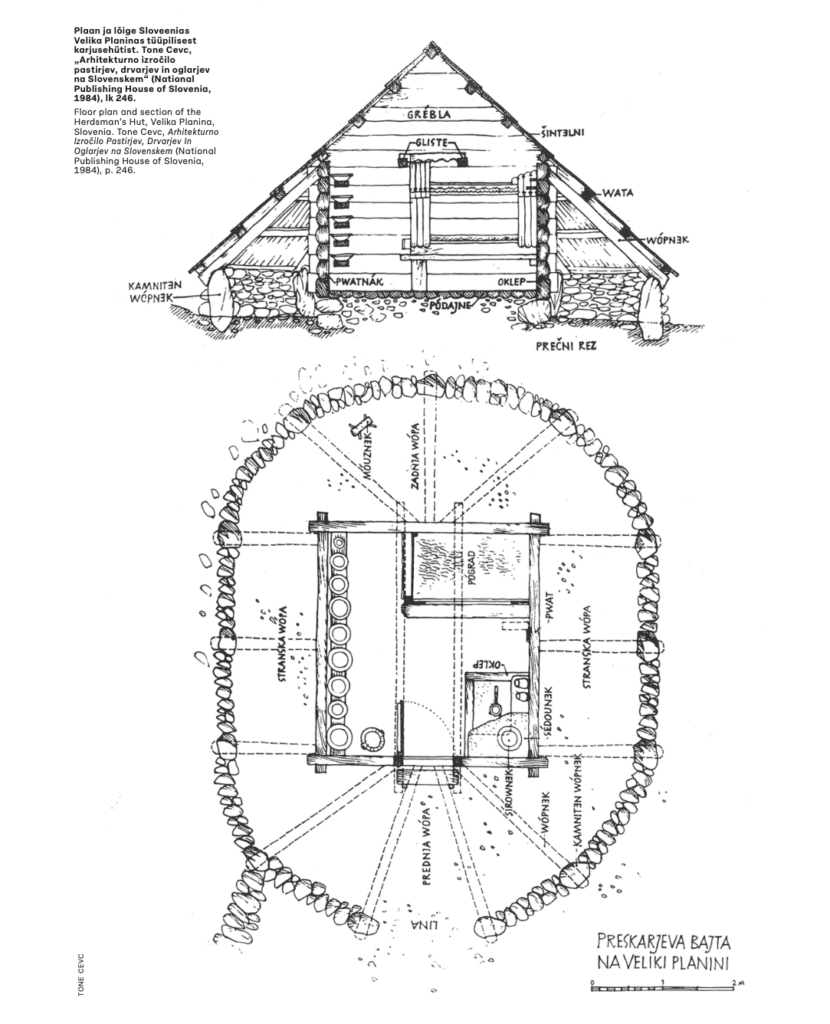

EG: We defined the term ‘vernacular architecture’ as something made through centuries and generations, with communal knowledge and by local people, not so much by architects. Vernacular architecture does not have an author behind it. Vernacular architecture also has no perfect type or archetype. One of our common references was the Herdsman’s Hut in the alpine mountain pasture of Velika Planina in Slovenia. A small rectangular cell for a shepherd would be surrounded by another ring of structure—the zone between the interior and exterior, where sheep lived and retained heat around the living space for humans while also emitting the heat of their bodies. It presents a symbiotic and spatial relationship that is effectively based on energy consumption and living together. The Herdsman’s Hut was constantly adapted through the centuries. It is very important that when we talk about the vernacular, we are not stuck with one specific image.

RR: Do these Herdsman’s Huts still exist?

EG: They do, just as you can see in the catalogue, but ironically, they are often converted into Airbnbs and upgraded with heat pumps and thermal insulation. So, the original concept is completely lost.

RR: You start the introductory essay of the catalogue with the year 1923 when Le Corbusier published his canonical book Vers Une Architecture. The essay takes us elegantly through key events, thinkers, projects, and technologies that have shaped architectural design over the past 100 years up until today. What did looking at this period offer to your research and understanding?

EG: Taking a hundred-year retrospective provides a symbolic period to reflect on. We start with Le Corbusier as an individual figurehead of modernism in contrast to what we consider to be vernacular, which is a common and anonymous development. The shift from vernacular to modern thinking was obviously not immediate, but the hundred years do illustrate how architectural design has gradually become less about local means and has increasingly been shaped by global technologies and international standards. For example, take central heating. Central heating was also applied earlier, but modernism introduced it on a large scale. Before that, one had to think about the distribution of heat around rooms and bodies as an integral part of architectural design. Since these concerns were made redundant by technological inventions and physically hidden into walls, floors, and ceilings, architectural reactions to such ecological issues were no longer developed. On the other hand, a quick overview of the past 100 years of architecture history shows us how the ecological concerns of the last decades are not completely new to the architectural discourse. Previous attempts to address them include, most famously, Buckminster Fuller’s and Oswald Mathias Ungers’ work. However, architecture at large was dealing with other concerns.

Üleval „Baldahhiinvoodi“, kaastöö Something Fantasticult. All „Andaluusia sisehoov“, kaastöö SOLARilt.

RR: Let us look at a term that plays a central role in your research and writings—i.e., ‘ecology’. How do you define it?

EG: One reason for choosing this term was that we did not want to use the word ‘sustainability’. I will loosely quote Timothy Morton here, an English writer and philosopher we interviewed for the catalogue. They describe sustainability as a means to sustain the status quo—a state of no changes. But the status quo has led us to our current situation, where we have to address the greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint of the construction industry. So, it does not make sense to sustain the unsustainable situation and pretend that after making some small changes, we can go on with business as usual.

‘Ecology’ stands for something broader—a complex relationship between living and unliving entities, where architecture plays a significant role in shaping them, and vice versa. We do not have specific formal parameters to measure ecological aspects of architecture apart from measuring the efficiency of technological devices and built-in products (e.g., thermal insulation). But I really find it important for the architects to imagine and propose how to include ecology in the design from the beginning, just like we do with structure and load-bearing walls. With our project, we argue that architecture lost its capacity to deal with ecology as it used to, and technology allows a quick measurable way to, for example, resolve the required interior temperature standards.

RR: You claim that technology has become ‘ecologised’. What do you mean by this?

EG: As practising architects, we have become very frustrated with the current situation where you are required to apply overwhelming amounts of heat pumps, solar panels, heat recovery systems, insulation, and so on to make a house sustainable. These requirements are measured and applied through demanding regulations, which have become barriers to developing a more nuanced architecture that would address ecological issues in a different manner. It is much more difficult to measure the energy usage of a building as an organism, focusing on its use by its actual inhabitants and the microclimates they create. We are not against technology, but we are critical of the fact that today you can make any house ecological by simply adding more and more technology to comply with the regulations. At the same time, many houses that would address ecology in unconventional ways never get built as it is often very difficult to prove their ‘efficiency’ through the lens of formal regulations. Therefore, it is not architecture that is evolving according to its environment, but technology that is being ‘ecologised’, which ironically discourages experimentation and prevents further progress in architecture.

RR: This is what you mentioned when referring to Morton—it is just about sustaining the status quo.

EG: Yes, it is a sustainability trap.

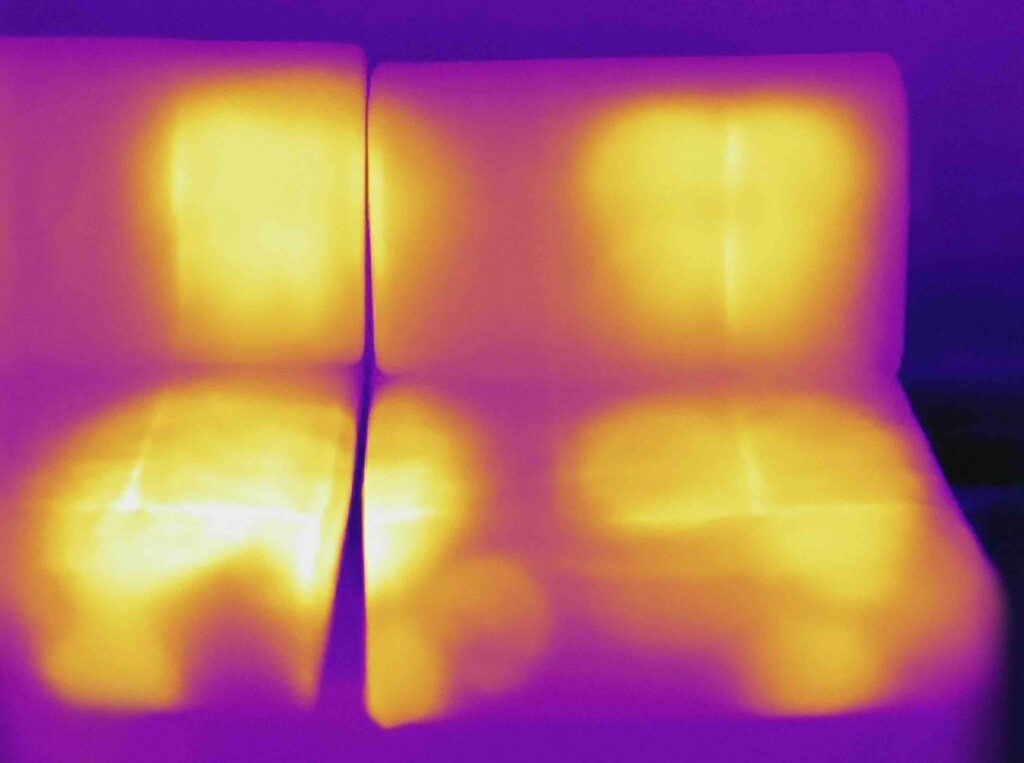

RR: With this in the background, let us discuss air. Technically, interiors with a stable temperature are very energy-consuming. What role does thermal comfort play in designing spaces?

EG: We are addressing this question very directly with the title of the exhibition and catalogue itself, where the +1 and -1 play a significant role in discussions about temperature and comfort. A contemporary interior is often heated up to a stable 20–23°C, but from a biological point of view, there should be more variation. For example, a cooler temperature is more suitable for sleeping, while spaces for taking a shower can be temporarily heated. Temperature is directly related to function, and from a vernacular point of view, it had many more gradients from one space to another or even within a space.

RR: As a practising architect, where do you see possibilities for intervening to achieve less dependency on technology and be more attuned to vernacular thinking and designing?

EG: I think one interesting discussion concerns the mentality and behaviour in using spaces—for example, using them seasonally or with different temperatures. Changing these things does not usually require a spatial intervention but a more general educative approach. In Slovenia, such topics are not very widely discussed with, say, the clients. Everyone just wants to be comfortable. Importantly, though, the aim is not to be less comfortable but to be more attuned to human needs. Chronobiology is a field that focuses on biological rhythms. Its studies clearly show that a constant 23°C is very unnatural—a temperature gradient might be much more beneficial.

Photo: Roland Reemaa

Currently, we can witness a phenomenon of extreme discomfort becoming popular and attractive—people are taking ice baths, time-restricting their eating, etc., all in the name of health. The fact that discomfort becomes a luxury experience obviously does not align with ecological design and can even have the countereffect of making such experiences seem unattainable to the general public, but it shows alternating environments are a desirable part of human life.

Furthermore, I think it is very important to remember that, as architects, we do not have to address these concerns alone. There are multiple other sectors that are interested in this field and studying it, and we should collaborate with them. Architecture is only one tiny part of the global ecological crisis, and we should not get caught up in an echo chamber.

We are not against technology, but we are critical of the fact that today you can make any house ecological by simply adding more and more technology.

RR: There have been numerous theoretical and practical attempts in history to ‘ecologise’ architecture but with little mainstream effect. Why, if at all, should current times see bigger changes than before?

EG: Ecological concerns remained on the fringes of the architectural field, as well as general social consciousness, up until the 1950s. In the sixties, people grew more aware of how fragile the world was in their hands, as can be seen in, for example, counterculture and hippie movements. Only then did the topic enter the architectural discourse, and even then only marginally. Today, we are in a much worse environmental condition than 50 years ago, and you cannot even think of architecture or construction without thinking about its impact on the environment—we simply do not have a choice but to make it the mainstream discourse.

RR: The term ‘ecolological’ in today’s context opens up a wide variety of ways to enter a dialogue with the environment, and not only measurable ones. Considering our discussion and the climate anxiety looming over us and the field of architecture, where do you position yourself with regard to the opportunities and challenges in the profession?

EG: This question pops up very often; an extreme, although relevant, version of it is whether we should build at all anymore. Undoubtedly, the role of the architect is changing as we are increasingly working with adaptive reuse projects and renovations of existing building fabric. But there is still a lot of ‘architectural’ work to be done with new spatial layouts, material selection and applications, and integrating all these aspects into coherent designs, whether we are renovating or building anew. The focus and the position of architects have changed, but I do not think the profession is becoming less relevant. If anything, it could be more relevant than ever if it addresses the situation critically.

Our project has gained quite a lot of attention in countries like Germany, Austria, and France, as well as in the northern part of Europe. High-altitude countries and northern countries have had to deal with the heating of houses for centuries, but today we are increasingly talking about cooling them too. Many of these countries are now emerging as forerunners in alternative energy solutions, including their implementation. For example, the energy efficiency-related regulations in the German state of Bavaria are at a very high level, but at the very top is an experimental classification, which allows to override some of the regulations in order to build and test innovative, experimental concepts. This is not an option in Slovenia or most European countries. I find it ironic how we think that our society must be more advanced than the previous ones because of all the formal bureaucratic regulations we have put in place, all the while these very regulations encapsulate us and limit our own curiosity, experimentation, and development. Only the standard solution, which falls within the regulations, is permitted.

RR: It seems to me that we have lost not only our practical sense in dealing with interior climate but also a ritual one.

EG: One of the simplest yet most meaningful and profound rituals is gathering beside the warm stove during cool evenings. The stove was not only a heating device, but a generator of social relations, the centre of communal living. In fact, we still appreciate this so much today that we install stoves in our homes just to produce this feeling and revive the ritual, even though we generally do not use them to heat the spaces as we have central heating systems in place. This is a rare example of energy-related rituals still practised today, no matter how devoid of its multilayered original function and purpose the stove has become.

ROLAND REEMAA is an architect, lecturer, and founder of LLRRLLRR studio.

HEADER photo by Klemen Ilovar

PUBLISHED: MAJA 4-2024 (118) with main topic AIR