Interview

‘I am still an architect, but for me the profession has taken on other colours. ‘

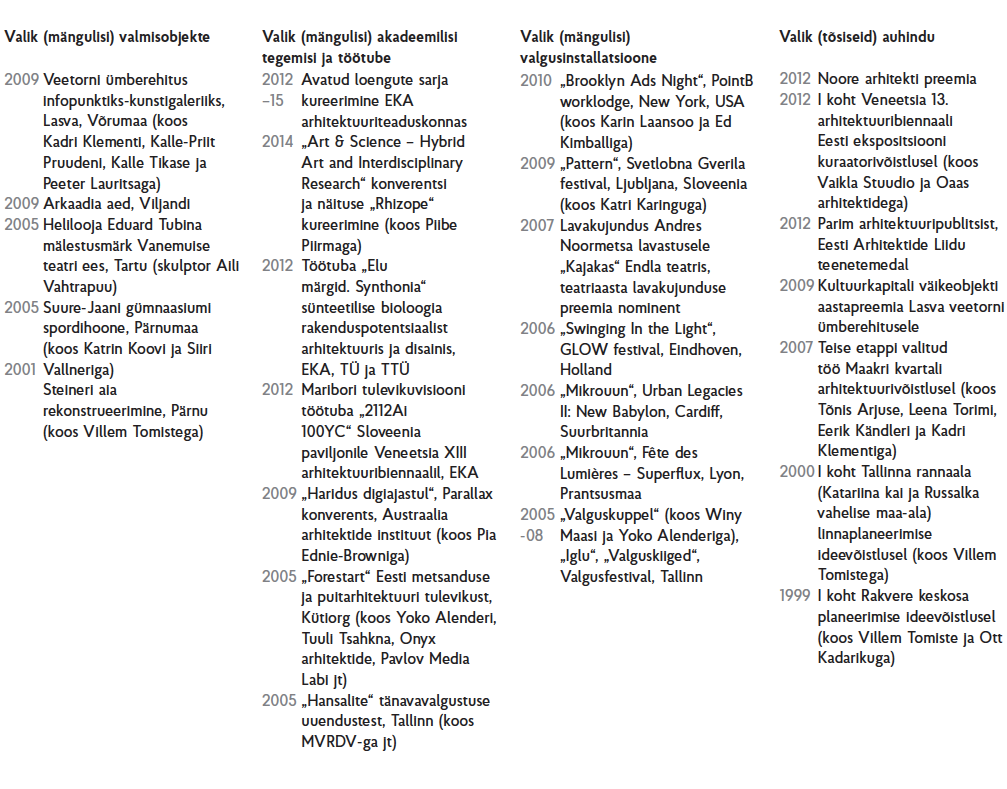

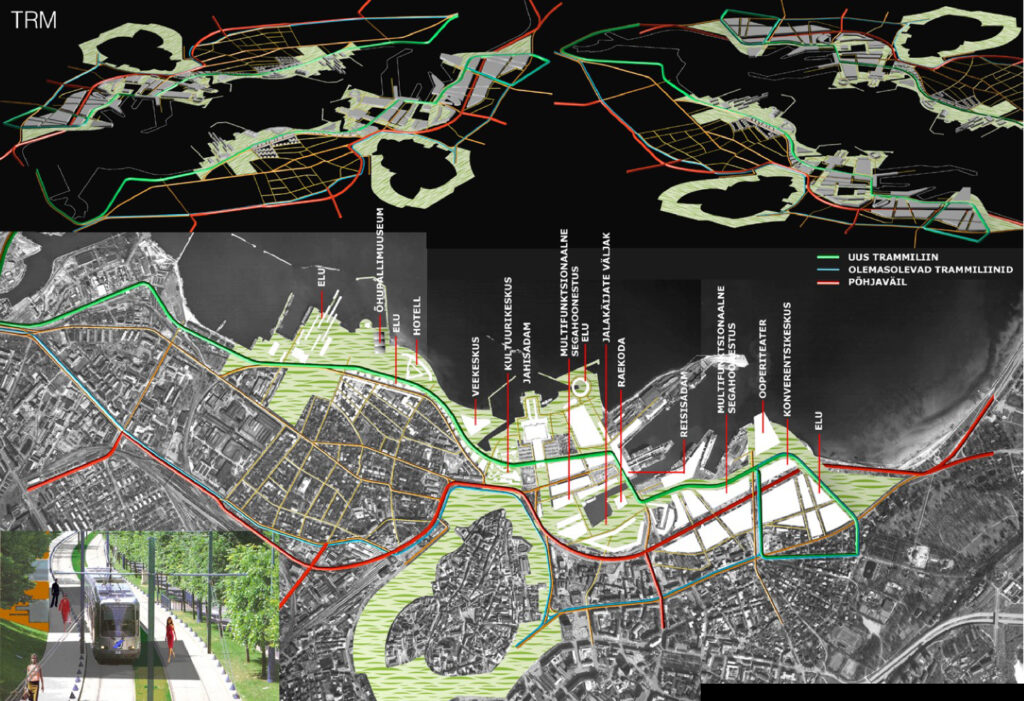

VERONIKA VALK-SISKA (1976) is an architect, laureate of Young Architect Award 2012. She studied at the Rhode Island School of Design in the US and graduated from the Estonian Academy of Arts. She completed her PhD at RMIT University School of Architecture and Design in Australia. She has constructed both public and private buildings, designed interiors and landscapes, won some 30 prizes at various architecture and planning competitions as well as published a number of critical essays on architecture and urbanism since 2004. As a firm believer in „architecture as initiative“, she is one of the key initiators of Kultuurikatel creative hub on Tallinn waterfront. She directed research at the Faculty of Architecture and lead the PhD program in architecture and urban planning at the Estonian Academy of Arts in 2013-2017. She has been an editor of architecture, design and urbanism pages at Estonia’s main cultural weekly Sirp and monthly Müürileht. In 2015 she became an advisor on architecture and design at the Ministry of Culture and has helped to kick-start the Spatial Design Expert Group by the Government Office of Estonia.

For Veronika Valk-Siska, architecture neither begins nor ends with a design or a building. Her career in architecture until now can be read as a reflection of an increasingly expansive understanding of what architecture could be.

For Valk-Siska, architecture is definitely more than just building, even though building projects are certainly part of her practice, albeit that even when her work is architecture proper, it is not always exactly meeting the conventional expectations of what architecture is or should be. Her work, whether produced under her own name or under the banners of Kavakava (between 2002 and 2005) and Zizi & Yoyo (from 2005 until today), intervenes in the built environment, at the intersections of architecture, art, and spatial agency.

Over the years, the focus of Valk-Siska has increasingly shifted from making architecture to enabling architecture. She has subsequently worked as a journalist stimulating a public interest and appreciation for issues pertaining to architecture and the built environment. She did her PhD and has been working on the advancement of architectural studies when she became the head of research at the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning of the Estonian Academy of Arts. And recently she is addressing issues related to the scale of the whole country as the Ministry of Culture’s adviser on architecture and design.

We spoke over Skype at the beginning of 2018, when Valk-Siska was in the process of moving to a new apartment while enjoying her maternity leave, which did not stop her from attending a State Real Estate seminar that week, where she had reiterated her point that Estonia lacks a comprehensive vision on the built environment. ‘Investors, and the government, usually look at property from a narrow financial perspective, without the kind of holistic view we try to promote with the newly created Spatial Design Expert Group, which has a mandate for one year, to kick-start new approaches. Part of it is our suggestion to create an office of state architect, who should oversee the spatial implications of developments in Estonia, to help to plan the country and to measure the value and impact of design.’

You are critical about the current condition but isn’t architecture in Estonia in a good place right now?

The economy is on the way up, there are a lot of private sector commissions, and many public competitions right now. Estonia is one of the few European countries where there are still plenty of anonymous competitions which everyone can enter, offering opportunities for young architects to compete for jobs. This is to a large part due to the Estonian Association of Architects, a key player in advocating, preparing and running competitions.

Despite this momentary economic growth, Estonia will unavoidably have to confront the demographic challenge that even in the most optimistic scenario the population is not expected to grow in the coming decades, and according to every less optimistic prognosis will actually see a population decline. Given this prospect, how much new architecture does Estonia need?

We are probably not going to enjoy this current building activity for too long, which would allow us to ask what we need today and how we can do better for tomorrow. I am convinced that there should be more coherence between decisions which are impacting the built and natural environment and which are often made in isolation. And right now, there is too much emphasis on the spreadsheet and the financial aspects, taking the direct costs as the determining argument for basically everything. And the lack of coordination between different ministries and governmental organizations means that conflicting decisions can be made without anybody noticing it until it is too late.

Could you elaborate on that?

There is not enough long-term planning in Estonia. We desperately need a better coordination to align decisions and to assess their spatial consequences. For instance, if you build a road, it is not only a strip of asphalt connecting two points for an economic benefit, but it is also affecting the living environment. So, in the narrow sense it is nothing more than constructing a road, in the broader perspective it is changing the built and natural landscape and the lives of the people. With the Spatial Design Expert Group, we are advocating for a better coordination and collaborations among public sector institutions and governments.

You are trained as an architect. Is this kind of work on the level of government and policies still within the field of architecture for you?

I am still an architect, but for me the discipline has taken on other colours. As a practicing architect I realized that you have usually little or no impact in drafting the brief. I feel there is a role to play for me as an architect, at a certain distance from the actual design process. As an architect you can take a position by either participating in a competition or not, but you have a limited influence on the public discourse about architecture, cities, landscapes, and the living environment. That was for me the reason to move into journalism and work as an editor, to engage in the public debate, to stimulate discussions and awareness about the built environment. But obviously, popular media don’t allow you to dig deep, which prompted my move into academia.

There I was confronted with the situation that architectural research and the practice of architecture have become disconnected. I was approached by RMIT to do my PhD in a practice-related research which made me fully aware of the values this kind of research could bring to the table.

In other words, what I am trying to say is that I realized that you can take on different roles as an architect without being the designer of a building but still remaining within the field of architecture. I am not unique in this sense. I see lots of architects in Estonia taking on different roles, moving from designing architecture to for instance neighbourhood activism, where they support local groups to improve the quality of their environment. Even if they do not assume the role of designer, it turns out that they work architecturally, using their expertise, for instance, in interpreting planning drawings, which is extremely helpful for a community to understand and articulate the condition they are in. Many architects are also involved in teaching. So it’s not just me but a whole generation that is operating like this, bringing their skills as designers and deploying different tools and instruments to advance the quality of living environments.

What could be those different tools and instruments?

For me, there is a great promise in materials sciences and synthetic biology. They provide opportunities to develop a new kind of architecture, and they could radically change the way we understand architecture. In 2012, I conducted a synthetic biology workshop “Synthonia” which ended up as a travelling exhibition. Inspiration for this largely came from meeting Oron Catts and lonat Zurr, who run SymbioticA research laboratory in Perth, Western Australia, enabling artists and researchers to engage in wet biology practices. Their perception, their investigation and observations of “life” have indeed had an impact on how I regard the future of design practice and possibilities of an architect to engage with new developments in culture, including science, technology and the concurrent engineering paradigm. The development of biotechnology is exerting a profound influence on how we will perceive, use and shape the world around us – the living organisms – in the future. The pioneers of synthetic biology and geo-engineers promise us new materials – medicines, fuels and chemicals not found in nature; they promise a better world and a triumph over climate change. But do these scientists and engineers grasp the field of influence represented by biotechnology in today’s cultural space and understand the desired future developments?

How has the broad scope of your different activities in the field of architecture impacted your understanding of architecture?

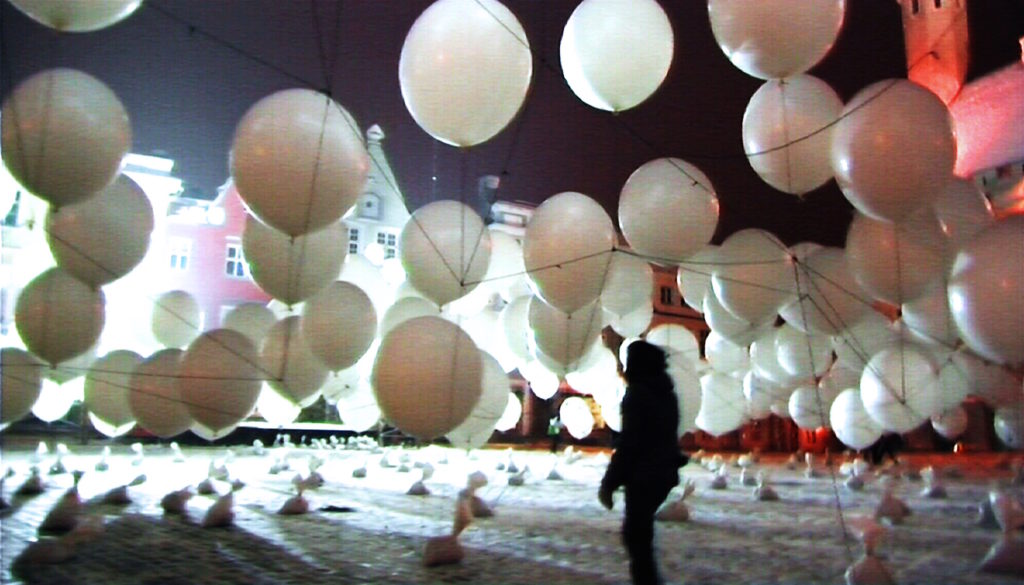

The key is investigation of “life”. The search for vitality expresses itself in my work through the offer of the “joyful” and “playful” which are usually not mentioned in any of the briefs of commissioned work. An architect is typically asked for pragmatic solutions — for a building to function logically and perform ecologically, for a design solution to be energy efficient, for design and surfaces to be easily maintained and so on. In my practice, I have demanded something more from the outcome beyond the pragmatics — I have searched for ways to integrate the “playful” and the “joyful” in buildings such as in Suure-Jaani sports centre, in public spaces, like the monument for the composer Eduard Tubin and urban installations for Festivals of Light. I see it as “embodied generosity” of practice, something which inherently increases the quality of solutions for built environment even if no one initially asks for this in the commission briefs. But it also applies to my teaching and curatorial work, where I try to offer similar playfulness.

To come back to what you have said at the beginning of this conversation, given your career path shifting from being an architect to becoming an editor, moving into academia, and now being an advisor on architecture and design at the Ministry of Culture, could this office of government architect you are favouring, actually be your next job?

If there was an opportunity I would certainly be interested to explore it, but there are so many people in Estonia who would be very good at it. And I am not sure if the focus should be on an individual. As we may see in the Netherlands and Flanders where they have government architects, it is actually an office, an institute and not so much a single individual.

For an outsider it seems that Estonia is small enough to be able to get its act together and create a high standard for its living environment. Why do you think this isn’t the case?

Part of being a small society in our case is that there is not much hierarchy. Estonia is very horizontally organized, and people tend to be individualistic. This means that everybody and everybody’s interests are treated equal and considered equally important. So, to achieve a coordinated outcome in terms of planning is difficult. The aim of the Spatial Design Expert Group is to involve all parties to operate collaboratively. But we need rules and regulations to structure this and we need to somehow overcome the fears that someone else is making the decision. So, we try to learn what happens in other ministries, by making our group work as a communication platform, bringing in people from different ministries to meet around the same table. People were actually surprised that it had never happened before. These meetings turn out to be extremely useful because people start to understand what others are doing and why, and they begin to develop a shared vocabulary, and perhaps even a shared frame of reference. Hopefully it will lead to what the Germans call Baukultur, a comprehensive culture of building. Right now, there is a gap between the Planning Act and the building regulations and we need a holistic view to bring them together.

You try to apply a similar rethinking on the building industry, for instance when it comes to timber.

That is another largely uncharted territory here. Having so much forest, the timber industry can be much more competitive. We already export two thirds of the timber production, 95% of timber houses go to more than 50 countries. But the timber industry rarely hires architects; they mainly operate as subcontractors, delivering whatever is requested. While with all the advancements in digital fabrication, there is an enormous potential for the wood industry to become more proactive product developers. Many of my architecture students are really with one foot in digital fabrication and this allows for different kinds of collaborations between architects and the industry that was unimaginable 10 or 20 years ago. You can do projects in a totally different way. But if the industry at large, with a few exceptions, is not ready nor open for this, the question for me is: what do we need to do to change this? In my opinion, the answer lies in offering a better setting in which designers and the industry can come together. Architects are not sufficiently aware of the potential of the industry, and the industry is too self-contained and too comfortable working as it has been doing for long, without investing in innovation. What I see through the work of my doctoral students Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam is that collaboration could help to bring the timber industry to a completely different level and sophistication and it would give Estonian architecture a great opportunity to brand itself as a place excelling in timber technology.

Speaking of forests, a substantial part of Estonia is non-urban. What is the take of the Spatial Design Expert Group on landscape?

We are investigating how to overcome the purely utilitarian view of forests, agricultural land and even national parks. Part of the problem again is the fragmentation of expertise and responsibility. Estonia has joined the European landscape convention and its landscape policy is part of the mandate of the Ministry of Environment. But they are not in charge of, for instance, road construction which impacts the landscape in a direct and profound way. The Ministry of Economic Affairs is responsible for the construction in general, spatial planning resides within the Ministry of Finance, and there is the cultural dimension which is represented by the Ministry of Culture. Each of them has a say and an influence on the environment, but they do not necessarily share the same interests or ambitions. To remind you, at the government level alone there are more than ten different institutions and departments making decisions that have direct implications for the spatial quality of the country. In addition to the county level administration and the municipalities, all significant decision-makers for our future living environment.

Zooming in to the smaller scale of the spatial quality. What is your perspective on public space in Estonia?

If we aim to improve the quality of the living environment, it is of crucial importance to arrive at a better quality of public space. Public space is the starting point for everything that happens in neighbourhoods. In Estonia we like to speak of architects as guardians of public interests. There is a need for architects as advisers to balance interventions proposed by different user groups and to help visualizing what the combination of different spatial interests likely means in spatial terms. It is not so much a matter of design but of a visualization of the spatial potentials of the diverse interests. If the public opinion tends to be dominated by single interest groups, the function of public space is to somehow accommodate all those interests.

HANS IBELINGS is an architectural historian. He is the publisher and editor of the Architecture Observer and a lecturer at the John Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design of the University of Toronto. From 2004 until 2012, he was the publisher and editor of A10 new European architecture, a magazine he founded together with graphic designer Arjan Groot.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 spring edition (No 93).

PORTRAIT black-and-white photos about Veronika by Renee Altrov.