A new system was established in Barcelona during the Olympics – an interconnected and organised chain of 10 public beaches. Its parts adapt to the changing times: they let themselves be rethought and thus allow self-sufficient life to flourish.

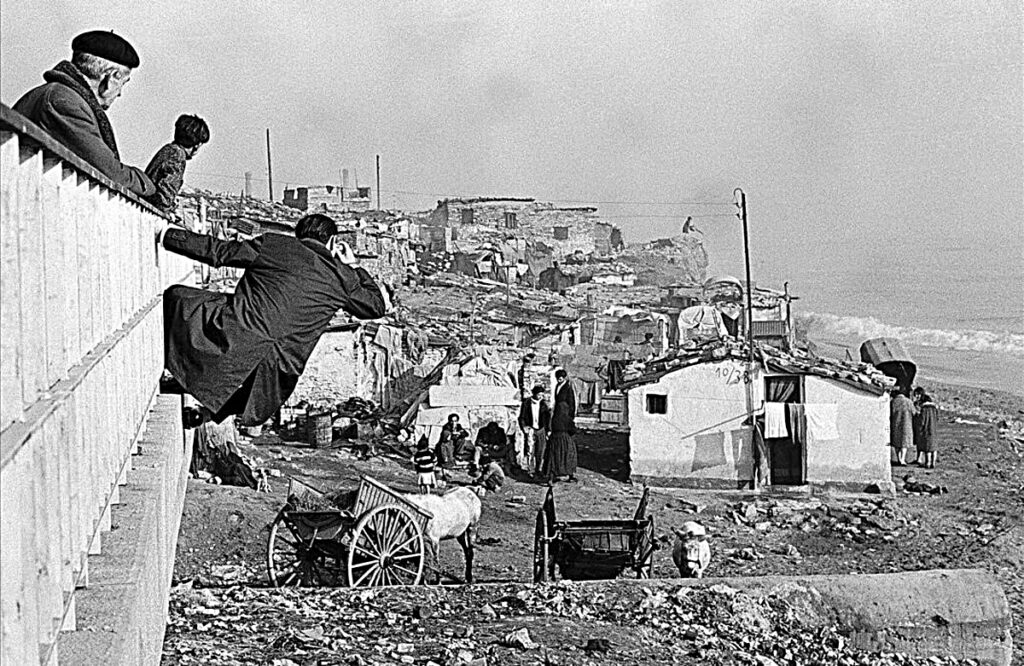

By the time I set my foot on the beaches of Barceloneta for the first time in 1997, the last self-perpetuating xiringuito (a temporary beach kiosk) had been removed three years before. During the renovations for the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, five kilometres of public beach were created. Many consider this area to be the main public space in the city. The Somorrostro district, with 15,000 inhabitants, and the beach of the same name were located between the modern Olympic harbour and Barceloneta as late as the 1960s. The beach had been cleaned overnight the previous time, too, and the first part of the beach promenade was constructed for a major event. Back then Franco was the “long-awaited” guest, who would be opening a new military exhibition.

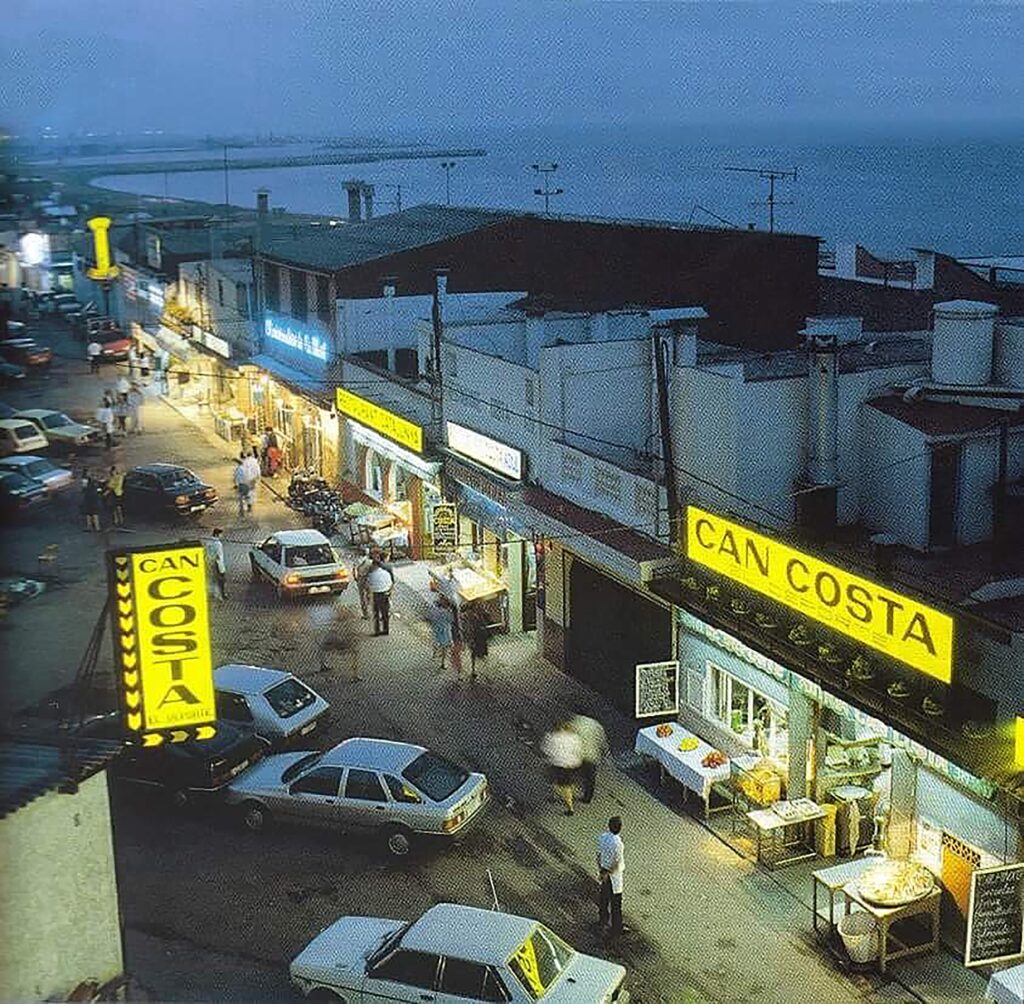

I saw the beach when it was still in its infancy – it was all completely new and bare. The kiosk venders had left their demolished huts and moved to the beachside districts or new food centres. This was back when you could get fresh crisps from the xurreria (a small business that specialises in making potato chips and xurros) and buy a bottle of Blanc Pescador from the nearby shop to enjoy on the beach. Palms had just been planted in the sand; the sea water was still polluted. The world was tuning in for the Olympics and the stunning coastline drew more and more tourists. Today’s vibrant seaside restaurant street of Passeig Marítim stood empty and abandoned for the first 10 years. First to utilise the space were service providers and clubs for locals. The old round-the-clock domino players set the mood on the empty beach after the sports festivities. Gradually xiringuitosmade their way back to the beach scene, but this time round they were purposefully added to the space as airy shelters that blended in nicely with the sand.

The palm trees initially planted in the sand didn’t seem to want to grow. During the Olympics, beaches were built by pumping sand from the sea, meaning the vegetation on the sea bed was disrupted. All in all, not the most sustainable way to create a space for human use. Recently, creating and maintaining beaches has been viewed from a new perspective, taking into consideration the sea and its inhabitants. After the seawall was created in 1687, the currents pushed sand up from the bottom of the sea to form the beach, thus making it a human creation. Beaches are extremely dynamic landscapes, and as such, to my great surprise, a storm once wiped Barceloneta beach away completely. For a couple of years the beach was replaced by a bluff, until people came up with a self-managing, multi-purpose solution – a bulwark. Natural erosion washes away 5% of the sand on beaches. In order to slow down this process, a network of breakwaters was constructed in front of Barcelona’s beaches. The system is invisible to the eye but regulates the currents so that they carry more sand to the beaches each year. In 2003 an artificial reef park called Parc dels Esculls was created. It is administered by the city zoo. The aim of the underwater park is to make the sandy sea bed more tranquil and to diversify the flora and fauna in the sea. Several hundred concrete structures are gathered in five main areas along the shore. The reefs were designed to provide homes to local animal and plant species, to increase fishery resources and to create a suitable environment for algae and organisms that purify the water polluted by swimmers.

A particularly endangered local species is the Barcelonetan. Initially built as a community for sailors, the area was supposed to have two-storey buildings. However, in the mid-19th century, heavy industry workers from the other side of the district faced a shortage of living space. That’s why the area was redesigned, with new buildings being as tall as those in downtown Barcelona. Altogether 36,000 people resided in the area at its peak. In just half a century Barceloneta’s population has declined by 60%. Today it is one of the settlements in Barcelona that is suffering from tourism the most. As people all over the world perceive Europe as one huge land of ice cream, xuerrias and other local companies that offer authentic flavours are going out of business one by one – this being the crime committed by this runny, rapidly melting substance. Even sardines are becoming harder to find in restaurants. As in all other parts of the Mediterranean, tourists demand that fish be big and white. Fortunately, the global trend of hanging out in department stores is starting to die off. In the meantime, Catalan cuisine has proved intriguing and inspiring to many people – new tapas dishes and the pursuit of molecular gastronomy are increasingly popular.

There is something calming about the arrogant Parisian approach servers take at restaurants: once again they live for themselves, rather than to cosy up to the passing hordes of tourists. However, let’s take a look at a tourist, even a Finn in Tallinn’s Old Town, who visits the city every few months, goes to all the same sights their compatriots have kept alive for decades – are they not part of the city, are they not creating a new sense of what being local means…? They are definitely more local and at home in Tallinn than the car-worshipping and ever-complaining people of Viimsi who use the city centre as a corridor to pass through. It is amusing to observe the pallid tourist groups on Barceloneta beach: they’ve taken a short plane trip to spend the weekend getting sunburnt.

The 10 beaches along the coast are just like the segments of a spinal cord, each transformed into something else following their unique everyday rhythm of life. People have come to enjoy fun times on Barcelona’s beaches for centuries. Beach time has always been a hit with tourists. However, the entire beach has only been open to the public since 1992. Not everything was completed right away, but a sort of harmony was established when all of the beaches became interconnected. This cohesiveness is available to everyone: it is a free public space, as opposed to the pop-up kiosks with their paid terraces and fenced-off areas. Today refurbished xiringuitos are back on the beach. The kiosks are only open during the summer season though, because their prices are fit for a tourist’s budget, but seasonal visitors tend to abandon their favourite destination for six months of the year. From autumn to spring, and especially in late January, there’s nothing better than making use of the long sunny days and walking on the shore from Llevant beach to Barceloneta, exploring how the intervening storms have redesigned the beaches. What Barcelona’s beaches come down to at their core is a continuous process of flowing through different emotions. These whirlwinds of mood form a unique sense of unity that breathes in sync with this dynamic city.

VILLEM TOMISTE is an architect.

HEADER: Xiringuito Street in Barceloneta beach 1990, Barcelona. Photo Archive (Arxiu Fotográfic de Barcelona, Col-lecció Arxiu Popular de la Barcelonata), registration number 7627, author unknown.

PUBLISHED: Maja 95 (winter 2019), with main topic Drift