Many things have gradually become so obvious that it is hard to imagine a time when we thought otherwise. And yet, there was such a time, and we were just as convinced of our notions back then. It would be silly to assume that our present understanding will last any longer than the previous one did.

To say that in what follows I will be describing what has taken place in the field of apartment building construction over the last 30 years would be clearly too ambitious. Changes are constant, and describing them would imply that they have been registered, systematised and articulated as generalisations. Nothing of the sort has been undertaken for the present article. I have simply lived as an architect and designed buildings for (most of) the period in question, and thus, I will try to draw out some of the more significant aspects from my own personal experience.

Such perceived changes might not reflect the reality. Perhaps it is the perceiver himself who has changed—or maybe it is how the world responds to him, and the kinds of things he encounters. Generalisations based on personal context might turn out to be inaccurate or even plain wrong from some other perspective.

Many things have gradually become so obvious that it is hard to imagine a time when we thought otherwise. And yet, there was such a time, and we were just as convinced of our notions back then. It would be silly to assume that our present understanding will last any longer than the previous one did.

Changes differ in their nature. Some things are constantly changing. Some things change all of a sudden, and then remain stable for a longer period. Some things change in a cyclical manner, switching their state back and forth. The nature of the change depends, of course, on the duration of the observed period and the observer himself—his ability to notice things, and the focus of his interests.

I will try to list a series of changes in areas that have also affected residential architecture. Each of them invites further targeted research, and the same probably goes for areas that I fail to mention here. Due to a large number of changing aspects, the present analysis is indeed often restricted to a mere list.

Changes in the mode of housing production

While seasonal variation and fluctuations in economic growth are periodical processes, many other changes appear to be non-recurrent and conclusive. It would seem that market economy and banking industry are here to stay. It would seem that, for now as well as the future, the practice that delivers us housing is property development. Private ownership of real estate seems to be the only thinkable way for real estate to exist.

Centrally coordinated Soviet-era housing construction was gradually replaced by a market-based one. This required a series of small initiating steps. The land reform and property reform were state-organised one-off changes in the course of which land and real estate became trading assets, circulating between private owners. This change had a huge effect on housing, and the change in the housing statute in turn had a huge effect on other areas of life.

Together with these state-initiated reforms, sectors that had not even existed before, or had operated on different principles, sprouted and thrived. Banking, property development and brokerage formed a kind of triple harness, where all the parties fed off of each other, but together, they tugged on the “carriage” of spatial environment in Estonia, including housing.

Even though these developments were one-off, they took some time to unfold. In that time, there were moments when one of the parties baulked or got stuck. This compelled the others to be inventive, which led to several business ventures that might not have gotten off the ground in the current, more stable environment.

As a general statistical remark, it should be noted that the decade of 1991-2000 following the restoration of independence was relatively slow in terms of construction activity. In a sense, all of this has contributed to the fact that things are now moving—perhaps slower than we would like, but the range of parallel developments is nevertheless a sign of a functioning society, a functioning mode of production.

Economic cycles

I witnessed the first boom in an architectural firm in the early 2000s. It was strange. We looked at the potential income for the next season and suddenly found it incredible how poorly we had lived so far. The forthcoming growth seemed to be exponential—because once on a roll, there can be no stopping any more, right? And yet, before these expectations could turn into tangible benefits, it became clear that the reality is different. Today, those who run architectural firms know that prosperous times are there to prepare for the rough times that follow. All the reserves will slowly be spent up, and huge surpluses occur only rarely and in fairy tales.

Legal matters

We can gladly acknowledge that the legal domain is constantly evolving. We have seen times when there were still some completely unregulated areas. We can concede that some areas are over-regulated by now. But all in all, the process of legislation is ongoing, and many sectors have a horizontal feedback loop through which regulators communicate with field-working practitioners, and through which we are able to contribute to state-building. It is true, however, that the field of spatial environment has been drowned in construction-related provisions in our laws, and the voice of architects is rather feeble in our regulatory texts. The sprawling property rights contain straps that cut into the flesh of urban diversity. For instance, mixing spaces with different functions within a single property lot is legally burdensome. Two apartment owners can interfere with the plans of a developer renting out commercial spaces in the same building, and vice versa. In order to avoid such disputes, experienced developers prefer buildings with a simple and homogenous program. This leads to solutions that are incongruous in the context of a city centre.

The legal framework comprises the developer and the architect, but also the municipal government, whose task is to coordinate the construction of the spatial environment. The laws that have once been enacted and brought into practice make it possible to consider every decision from a legal point of view. This is mainly done by courts—but in spatial matters, a court is like a randomly firing gun. Thus, municipal governments direct their efforts to preclude any court cases from the get-go. This decreases the amount of attention paid to the quality of space, meaning that certain preferences among public servants often appear skewed from the perspective of an architect.

Insolation is a concept known to every architect who has worked in housing design. The requirement to ensure access to daylight is actually in the discretionary powers of municipal governments, but municipal governments almost always prefer to regulate spaces with the daylight standard specified in recommendatory provisions. Since daylight is a measurable phenomenon, officials and lawyers are equally keen on it—every disagreement can be resolved by a projective analysis with an unambiguous result, meaning that there is no need to go to court.

In order to circumvent the rules, resourceful developers introduced something that has now been in use for a couple of decades already—the visitor’s apartment. A visitor’s apartment is a housing unit that is subject to different rules than regular housing units. In its original use, the term designated mainly apartments built on commercial land, but today, it could also refer to living spaces that get insufficient sunlight. Over time, visitor’s apartments have been regulated in terms of room-naming as well as fire safety, but the resilience of this very concept indicates some deeper faults in the regulations, or namely the kind of dynamic that is written into our legal domain, perhaps.

The combination of diversity-inhibiting property laws and insolation requirements has a withering effect on, say, perimetral buildings. The kind of city centre that was still dominant in the early 20th century would be impossible to build in the current regulative context.

Energy efficiency has come a long way—with just as much still left to go. The energy labelling statute was established in 2008. At first, it was thought that this will make windows shrink and walls thicken. In practice, the great burden it places has been carried by advanced technological systems, meaning that the regulation has had less effect on living conditions and spaces than it was initially feared.

Spatial changes

There have been times and places in which the architect is able to devise the whole urban environment, designing also the buildings and landscape in it. There have been times and places in which each bit is handled by a different party. There have been situations in which it is not even possible to design buildings as part of the planning. The current trend is that developers are increasingly dictating which shapes of buildings are permitted, and which are not.

Changes in building structure

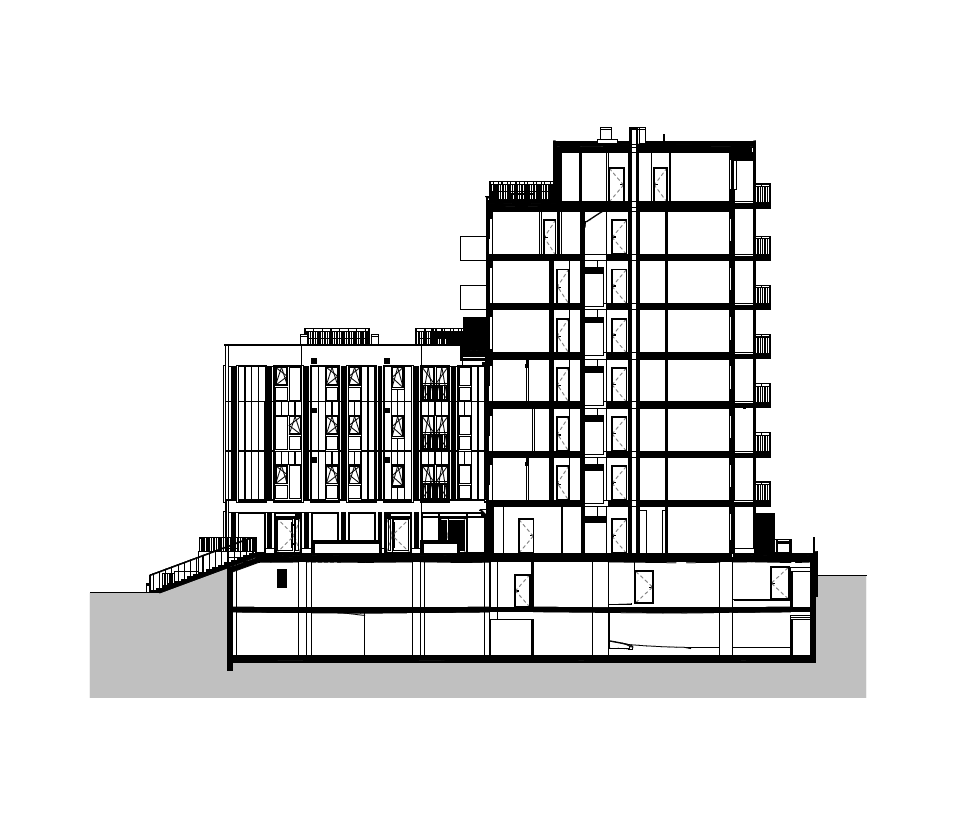

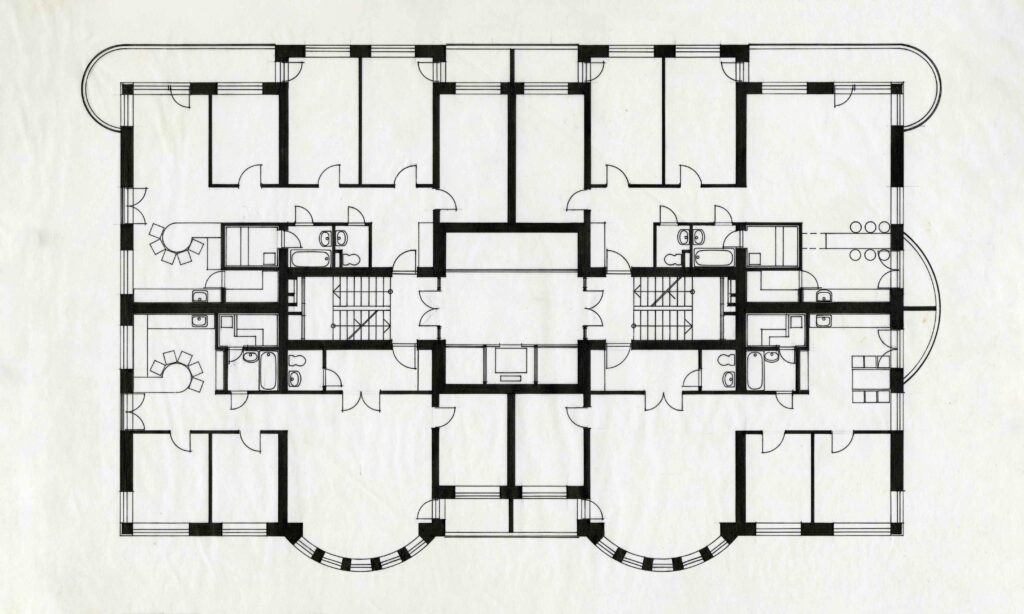

Entire repeated floors have given way to a slightly more varied reality. The average contemporary multi-floor apartment building has floors with at least four different plans—parking and storerooms in the basement, entrances and apartments with terraces on the first floor, intermediate floors with a repeated plan, and penthouses with even larger terraces on the highest floor. This order of things is rather foolproof and not given up easily. Having different floors involves connecting various ducts and shafts, which is sometimes the only challenge that the architect faces.

Every architect gradually learned the column spacing required by underground parking lots. There was a time when certain things were in harmony. There used to be a magical 8.1-metre module that could be used either for three cars, or a living room and bedroom, or by a construction engineer as a lintel for interior ceilings. Today, there is a legally set standard for parking space sizes, for which 8.1 metres is too little. Larger column spacing is rejected by constructors, and rooms can no longer be arranged using that same module. In other words, the world keeps on changing.

Changes in apartment structure

One might suppose that apartments have changed in 30 years, but on closer inspection, the change is not that big. We have slowly embraced the open kitchen that helps to keep rooms in more reasonable and pleasant proportions, given the size of an apartment. Naturally, this is also useful for the developer—the building can be thicker and the apartments deeper. Since every apartment houses a life of its own, it is difficult to evaluate how many people actually enjoy this solution and how many simply tolerate it as an inevitability.

A changed developer

Developers have become institutionalised. Larger projects are carried out by larger developers, who have their own lines of credit, market niches and preferred design teams. Increase in professionalism has been accompanied by increase in self-assurance and the number of placed orders.

The corporative apartment bible is a collection of guidelines given to the architect by the developer. In the earlier years, it consisted in functional terms of reference, which the developer often had difficulties writing down, and the architect stepped in to help. Today, the situation is completely different. After a confidentiality agreement has been signed, the developer presents his own design guidelines, which could span tens of pages. The order might specify the depth of hallway cabinets and balconies, structure of awnings, proportions of rooms and list of kitchen appliances. On the one hand, it is good that the order is precise; on the other hand, there is little room left for manoeuvre in this world.

These apartment bibles could be repurposed as study materials for training architects, but so far, developers have considered the makings of a good apartment their own trade secret. This might slowly lead to architects working in the service of developers. Just think of it—a new corporative guild system.

Among less institutionalised developers, one occasionally comes across a designing developer, who comes and sits with the architect behind the desk, where he could then spend a day or two, tinkering with the plan and bombarding the architect with his own precious tips. Have you met one?

We should also note that a couple of decades ago, architects used to meet with the very entrepreneurs who risked and profited, but today, we only get to meet with their salaried employees. They, too, have more expensive suits and better cars than us, but their opinions carry less weight, and persuading them of something could well have zero effect on the further course of things.

A changed resident

The image of new residential housing built for young families has slowly eroded. Nuclear family still dominates the renderings of sales pages, but will not get any compromises. Rather, nuclear families have become the filler who move into places where others would not. Why? Because their financial capability is low. Apartments await first and foremost those who are able to get a bigger loan. Children’s playground is still the only small-scale object in the meagre yard area, but has lost its heart and soul. A change in the conjuncture of family structure types is both noticeable and measurable. Increase in the proportion of people living alone and single-parent families, changes in the population pyramid and mobility are some of the factors influencing the market.

While the property reform turned all Estonian residents half-forcibly, half-voluntarily into property owners, such homogeneity has eroded over time. In the ‘90s, a tenant was often a forced tenant, and a rental apartment was often forcibly so. Thirty years later, the picture is more diverse. Globally spreading peer-to-peer accommodation system, economic polarisation of the society and professional international mobility are growing the number of rental apartments. An apartment is no longer sought only for living, but also as an investment, the liquidity of which depends on its location and spatial plan. Rental apartments are even more reflective of the market, since they are more often sought for their sexy marketability than the apartments bought for living.

Changed structural elements and building materials

Indeed, technology keeps advancing, materials keep changing, and, from time to time, a wholly new product enters the construction market, which on closer inspection turns out to be an old friend in disguise. Fire safety and acoustic requirements tend to fix the types of building envelopes used. When it comes to load-bearing structures, reinforced concrete in its different forms remains in the lead, while wood has stumbled at the starting line. The architect is left with the task of designing the “coat” of the building—his choice of finishing materials and arrangement of balconies are expected to exude a wonderful freshness that should find its place in a real estate portal rather than an architecture magazine.

Coda: a lack of air

While this is not always the case, interesting spatial solutions are still often born out of some kind of excess. Excess means resources that have not been taken into account in the terms of reference or design-related restrictions. Excess allows the building to extend outward or upward, contain holes or cavities, be weirdly shaped or programmatically unusual. Excess might simply be some luxurious extravagance or an odd spatial component that later turns out to be very pleasant (or pointless). There can be an excess of money or excess of time; excess might lie in the natural or social surroundings; but architects have always been most delighted in the excess of space.

Excess of space is especially appealing for the architect, and even more so if it is accompanied by the freedom to realise it in an arbitrary way. This degree of spatial freedom is commonly called “air”. How much air is there in the building—how wide is the gap between the placed order and maximum construction volume?

Alas, apartment building projects have been deflated of air. This has happened on two fronts. Zoning plans specify the maximum footprint of the building, number of floors and total built-up area. The latter is often the product of the former two. This product also serves as the point of departure for the developer in devising the business plan. Each additional square meter means additional profit. It might seem that this proportional relation cannot extend infinitely—but in these parts, space has not yet densified to the extent that would begin to cut into the profit margin.

A devilish tradition that is also written into the building code stipulates that the built-up area comprises all the awnings, balconies and consoles. This favours the strategy of using up the permitted built-up area to the fullest, and multiplying it with the number of floors in order to maximise the total floor area. Hence we get plain buildings with vertical walls and repeated floors—buildings without air, without any excess. Architecture is reduced to correct design solutions and cool-looking facades. This does not necessarily give bad or unsightly results, but makes it hard to breathe.

Another point where air gets deflated is in functional terms of reference. Developers have set very precise limits to the sizes of apartments, rooms, kitchens, cabinets and storerooms. The ratio of total built area and saleable net area is experientially very clear. The limits are based on the clients’ ability to pay (or get a loan) so as to enable selling on the best conditions. The rules are well-intended, guaranteeing the basic quality of life and guarding against mistakes due to sloppiness or ignorance of the designer, but they also rule out any alternative solutions. Apartment plans lack the air that could be concentrated in a particular spot, or spread out evenly. There is no air to carry architecture further and beyond the utilitarian decorative minimum.

Could this change—and should this even change? I suspect that every era has had its own methods of efficiency that are solidified by interconnections across different spheres. Our current lack of air is encoded in the banking, property development and property sale sectors. Their operating logic is in accordance with the rules of globally dominant liberal capitalism, and in our case, gets expressed in the fact that the construction of housing has become a market-based activity. Thus, change seems to be possible provided that there is some kind of a shift in the global economy, or that we locally decide to put the production of housing on some other basis. Neither prospect is very likely.

It is noteworthy that contemporary apartment buildings of the more economical class are quite akin to Soviet-era mass-produced housing. The conjuncture of apartments, simple forms of buildings, repeated floor plans and reinforced concrete structures are relatively similar. Granted, there are differences in energy efficiency, acoustic separation between apartments and usually also the quality of construction, but a certain pursuit of economic efficiency has brought us full circle and back to familiar territory. The very same lack of air can be felt in both, even if the mechanisms that keep reproducing it have changed.

A changed architect?

Thanks for the consideration, but not really.

INDREK RÜNKLA works at Kadarik Tüür Architects. Previously, he has taught in the Estonian Academy of Arts, worked at Alver Architects and acted as the Advisor for Architecture and Design in the Ministry of Culture.

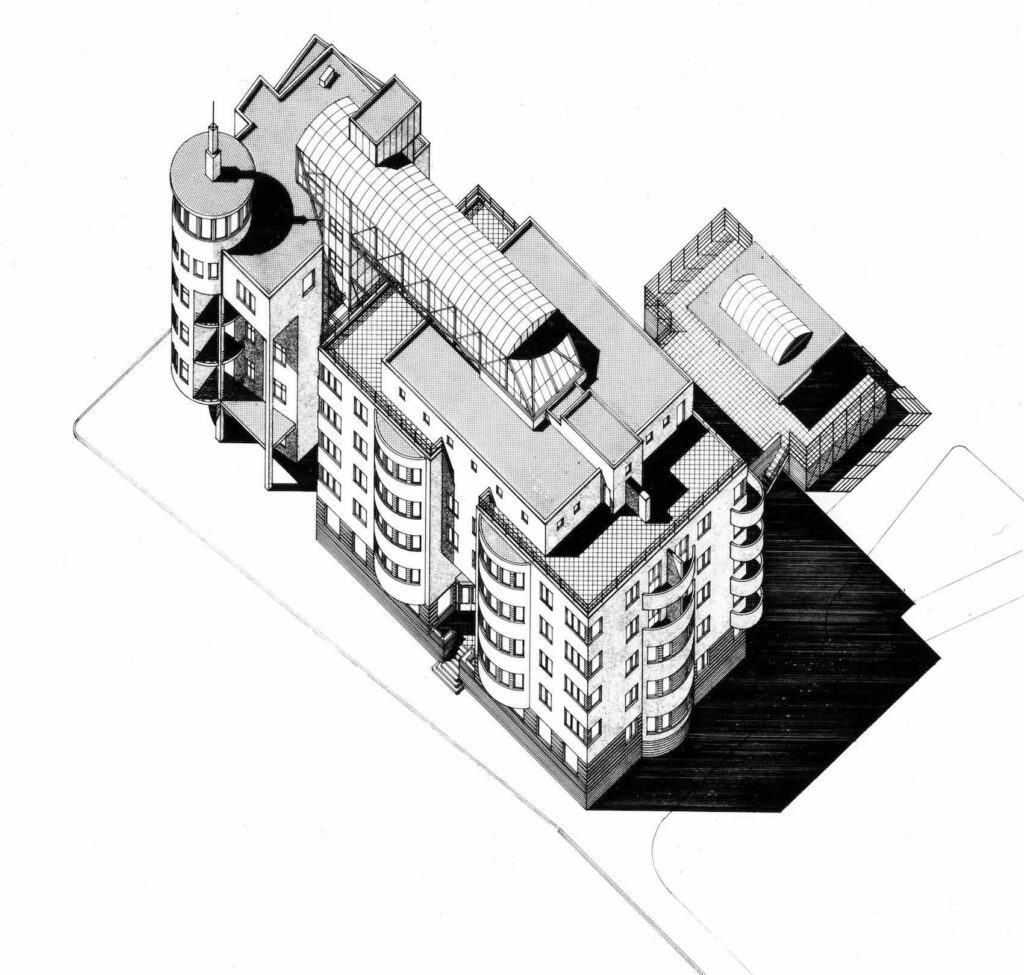

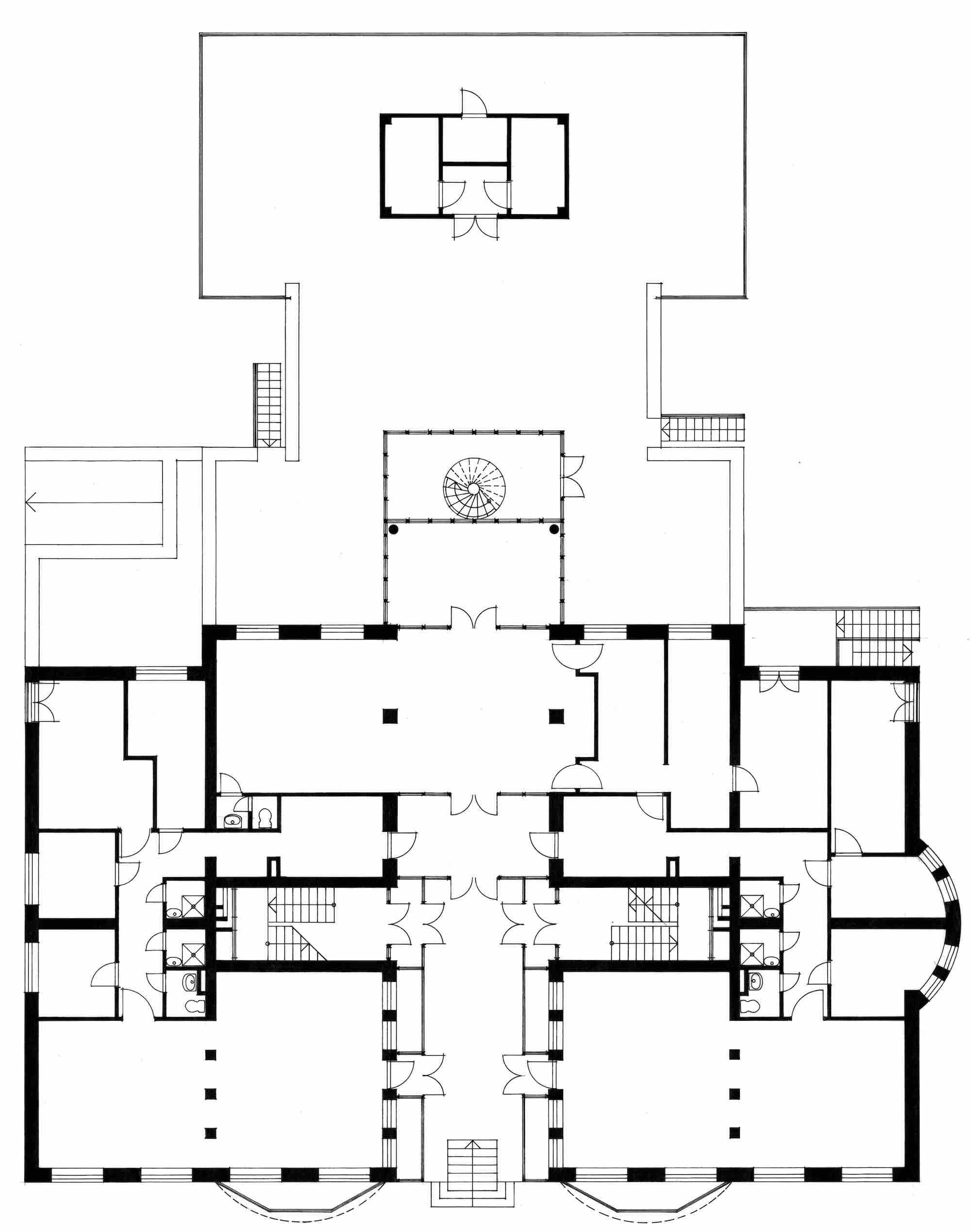

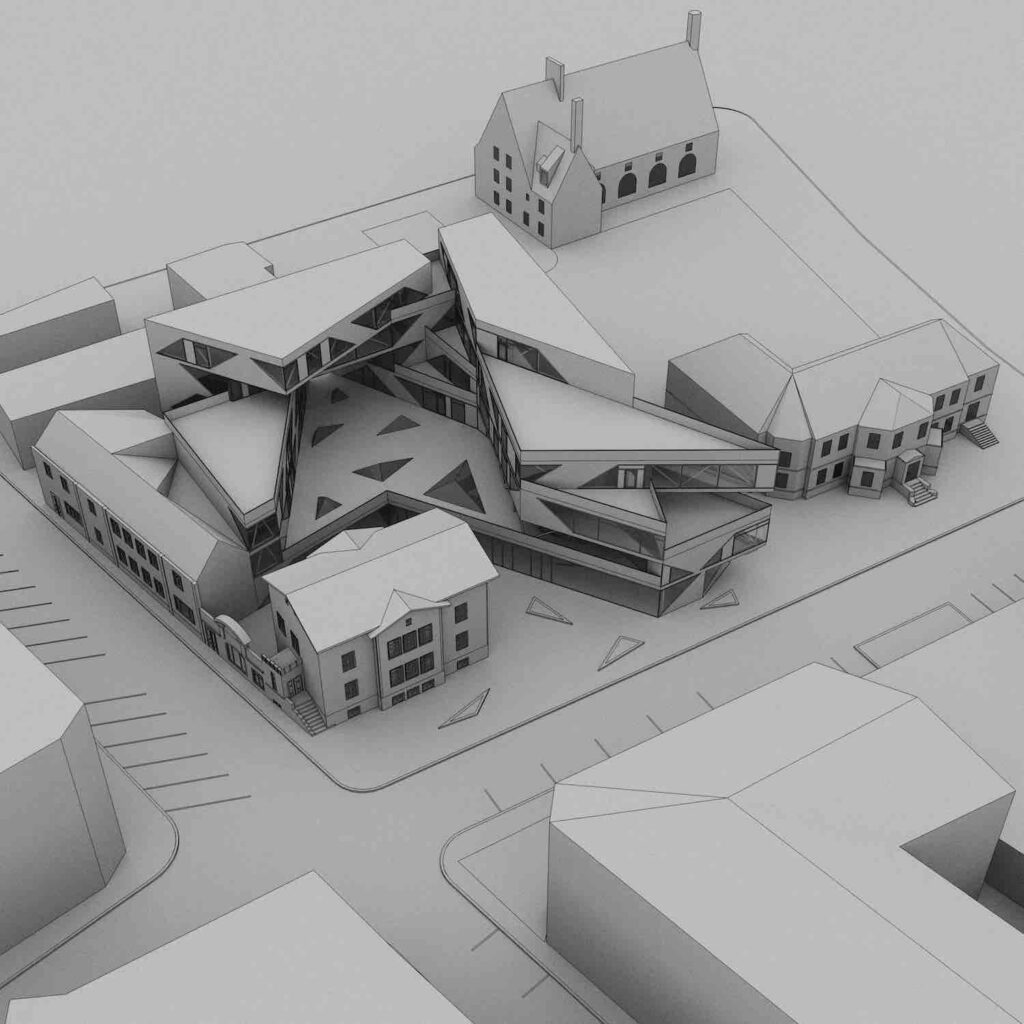

HEADER: The residential building of recent years are characterised by increased construction volumes. Toom-Kuninga apartment buildings in Tallinn. Kadarik Tüür Architects, 2015-2020. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 106 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions