Questions by Ingrid Ruudi

VILLEM TOMISTE is like a figure from the beginning of 20th century Young Estonia movement – genuinely European, deeply urban, and as such, slightly suspicious for the local conservative community. Unlike many architects who preach social benefits, he actually lives by what he promotes in his civic visions – urbanistically to the core, commuting on foot and by tram, avoiding over-consumption, and with a refined aesthetic sensibility. Contemporary spatial culture is, for him, a field of opportunities: extending from urban planning and landscaping projects to dialogues with contemporary music, the visual arts and various exhibition practices.

Once again, you returned from Barcelona last night. What did you see this time?

Nothing in particular. Barcelona is my place of retreat. I don’t have a countryhouse to stay at when I need a break. I suppose I would need a habit perpetuating from childhood to pursue that, but we spent our holidays in Pärnu or by the Black Sea, in Moscow or St Petersburg. So, now I go to Barcelona. It is a great place for tracking the logic behind urban evolution. When you travel to places, you may get a feeling that you know what a city is like, but in fact it renews itself every half a year. There’s a dynamic – some things come, others disappear. It is interesting to follow. Take a business or any other building complex, vegetation, a new park – is it going to work or not, or how long until the first changes are made.

It seems that you systematically visit all the prominent art exhibitions when travelling Europe. What does this mean for an architect and do these experiences permeate or reflect back from your own projects?

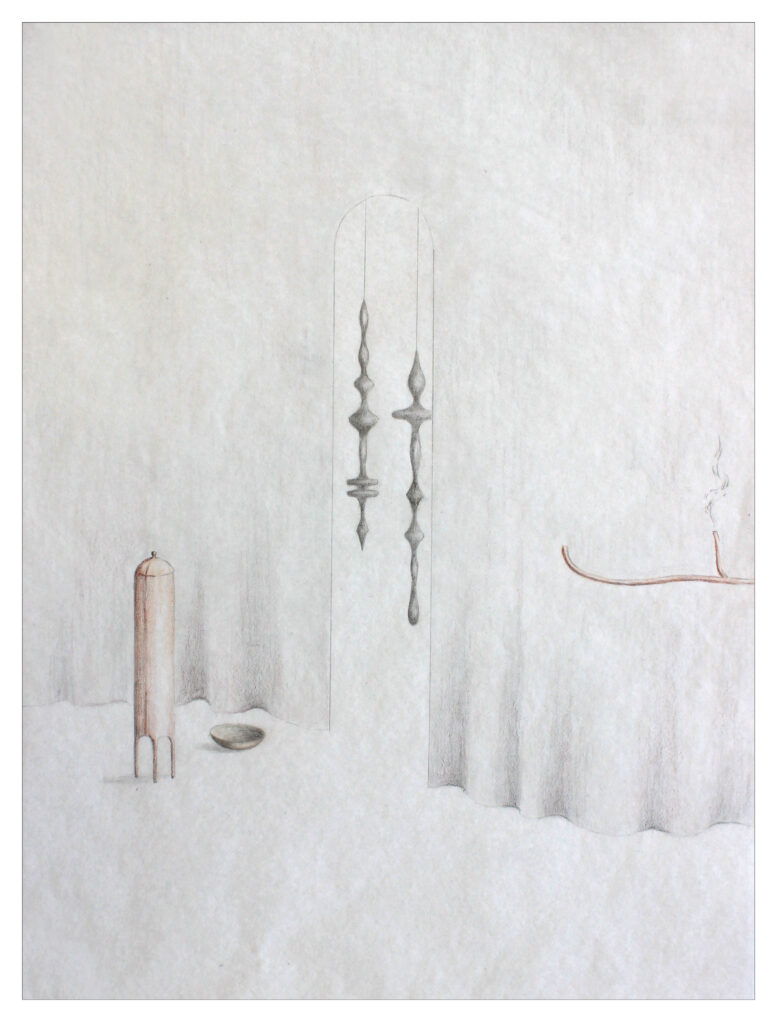

I have no ambition to make art, looking at it is rather a vacation or a search for something. It is like going to the forest to pick mushrooms – you go, you look, and you find. No doubt a lot of it is uninteresting but that just makes the discovery of the few cool things all the more exciting. You can really enjoy it then, cathartically. It is the same with contemporary music. A concert is a kind of workshop for me where listening spurs my thought process in a completely different way. Sound and space jointly often incite this effect. In Tallinn, a wonderful place like this is Niguliste Museum-Concert Hall where I attended quite a few concerts during the World Music Days this spring. I work alone, so my work process does not involve discussions with other people. The moments that lead to either self-doubt or an awareness, I have to catch within myself. In that sense, art is not a direct source of inspiration for me, although I am certainly more intrigued by pieces that touch upon topics similar to mine. At the moment my attention is on all sorts of machinery since I am building machines on the central square in Võru. The new solution for the square has two layers: firstly, the traditional elements such as paving, greenery and lighting – tentatively, the “operating system“ of the square – and then the suprabuilding, that is, all the programs and mobile gadgets that are in constant development. The Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art recently hosted an exhibition called Quantum that provided a platform for a dialogue between quantum physics and contemporary art. The work Cascade (2018) by Yunchul Kim exhibited an intriguing construction that I found similar to the widgets in Võru. Art addresses me when it deals with things that have no apparent function but which describe the modern day – I am interested in the aspect of contemporaneity.

Do you have specific preferences toward genre?

Mostly, the type of art that inpires me is installative in one way or another, like for example, Pierre Huyghe. His contact with nature interests me – people’s assumptions or attitudes toward nature or opinions on how different life forms should exist. Or Charlotte Mothi’s Duchamp prize exhibition at Pompidou, “The Wolf, the Lady with a Shell, Martin and the Couple“ where she created new installations and manipulated with lighting to re-interpret sculptures from the Parisian city space. Recently, the most thrilling experiences have come from shows where artists display mastery over various media – for example, Acqua alta (2015) by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, or Mika Rottenberg. Political subject matter can work if it is played out smartly; a certain degree of humour can come in handy. In Paris, the Palais de Tokyo always has something interesting in store. There are just so many biennials and exhibitions that there is hardly any time left for other trips – take Venice, Istanbul, Manifesta. Visiting New York two years ago I did not find the art scene as fascinating as in the European institutions. The focus was on established artists with not much room left for the unexpected.

Does conceptual architecture, the kind not meant for building, also speak to you?

I am not involved in making conceptual architecture, per se. A lot of projects have been left unrealised because people are skeptical about how an object might support itself, or because no similar thing has been attempted elsewhere. It is somewhat peculiar that the project for the central square in Võru was selected winner. The idea of the competition entry was to build urban gadgets on the square which the citizens can move around according to their preference – the smaller ones can be moved independently, the larger ones with the help of mechanisms. I proposed the first set of gadget prototypes in the competition entry, and later we developed these ideas further in collaboration with the City of Võru, to make them more adaptable. And all this works. But it is not a conceptual project, because it deals with practical issues – what defines a modern square, how do people use it, how to make it more attractive.

It is important for me to strive toward a universal language that employs geometry, a line, as one of its elements. This approach enables an object to adapt according to need, and retain its individuality at the same time. Raine Karp has said that first, the regulating lines have to be set up – this is not incorrect. The grid of the Võru square is not 8 by 8, but rhombic with a 60 cm increment, which allows controlling the whole while generating freedom, so that the idea may mutate according to need. The pedestrian bridge across the Admiralty basin was also a contextually evolving enterprise. The liftable part of the movable bridge is balanced by lighting that illuminates either the bridge or the embankment, depending on the situation.

I think there is no other Estonian architect with so many winning competition entries unbuilt as you have. What is the role or effect that such unbuilt works impose on architectural culture? Do you consciously draft competition projects that do not heed to compromise in terms of feasibility or client expectations, and end up second because of it?

Every single one of my projects is intended for realisation. The majority of winning entries that remain on paper are concerned with Tallinn seaside or public space. Coincidentally, looking at the winning entry “TRM“ for the 2001 seaside vision competition in retrospect, we find the Culture Hub exactly in the right place, a museum for machines in the seaplane hangars, and the bastion zone slowly evolving into an integrated public space. I hear the tramline will be extended all the way to the harbour soon, too.

Is the question of conceptual architecture even relevant in Estonia? Are there enough partners to form a dialogue?

Of course, it is important to carry on dialogue, art can emerge from reflection. I cannot say if there is conceptual architecture in Estonia, I am interested in the different opportunities to practice architecture and I know others who are as well. For example, Laura Linsi and Roland Reemaa, whose exhibition in Venice was charmingly simple and comprehensible, and so detailed at the same time. The sincere discussions and opinions that Margit Mutso contributes to contemporary architecture are irreplaceable for me. The list goes on. The organisers of the satellite programs of Tallinn Architecture Biennial also carry on, even if their architectural practice seems not very practical at first.

You revived Tallinn Architecture Biennial (TAB) in 2011 to sustain dialogue and architectural thought. You have said that a curatorial exhibition should be an experimental stage for architectural magic and in the context of TAB this statement has perhaps best described your own first exhibition. Which architecture exhibitions have you been enchanted by yourself?

François Roche inspired me with one of his exhibitions held in Paris in 2005 so much so, that it instigated a desire in me to curate an architecture exhibition. Then, a few years later, TAB was kicked off. Roche’s exhibition was called “I’ve heard about…Hypnotic chamber…(a flat, fat, growing urban experiment)”. The rules for an exhibition differ completely from those that apply for the built environment. Displaying completed buildings or landscapes in diminished scale in an exhibition space is not sufficient for me, I might as well go and see a show on model cars.

The international biennial landscape becomes richer and denser by the year. Has TAB established itself? Has the growing network and chance to look and see beyond everyday building work stimulated Estonian architects and broadened the view of municipalities? In what direction should TAB proceed?

The objective of TAB was to inspire architects to think outside the box and provide a platform for that in Estonia. TAB is one of the few biennials with an open curatorial competition and thus different each time. The biennial could keep functioning as a trigger that encourages the materialisation of ideas we think about anyway. It could keep creating possibilities for local practicing architects and refresh the scenery by inviting visitors. My personal goal is to involve not so much specialty magazines as general media. I have always preferred the level of reaching people via a daily newspaper channel to address an audience as wide as possible. An architecture biennial enables discussing complicated subjects at different levels – in specialty language at symposia, but in a more relatable way through the vision competitions. Participants can design buildings or plan urban areas for an actual location in Tallinn, explaining the topic as they go. After the third vision competition of the biennial which focused on the Viru square junction, the Tallinn main street project was initiated that has evolved into a construction project by now.

What do you think of the subject matter of this year’s TAB – “beauty matters“? Is it adequate in today’s world where there seem to be much more urgent issues?

We can feel one way or another about the issue of beauty, but it is relevant in both architecture and art. If architects do not bring up the topic of beauty and architecture, then these concepts will continue to be used in a conventional, outdated way. For me personally, it is exceedingly difficult to understand the pursuit of so-called old-school conceptualism in art. I have always been searching for my own geometry or line, and this search is ongoing. This was not cultivated at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EAA) when I was a student there, and it was a joy to find a diverse field of such explorations at KU Leuven where I spent a year studying my own practice. EAA has long followed the Dutch model from the 1990s, where primary focus is on typology, logistics, functions and then at the end some creasing of surfaces to top it all off. Studies have been based on drawing proposals with the aim of achieving flow and rationality. It is difficult to jump from this disposition to capturing location-specific phenomenology. When you are trained as a logistics specialist, you are not equipped to invest architecture with a narrative dimension or create unique geometry.

Touching upon aesthetics, it seems to me that your designs have become lighter over time, less robust, perhaps even more poetic?

Hmm.. I’m usually more interested in the robust. In the public space or business front it is namely robustness that injects verve into a building. At the same time, chaotic situations have to maintain systematic relations with one another. In this regard, the practice of Miralles-Tagliabue in Barcelona is a great example. Maybe I have simply got better at creating geometry over the years, I feel more confident in this regard. When you are younger, you are just combining different volumes.

Site-sensitivity is of course extremely important. Lately, I have been participating in a number of landscape competitions. An expert from the jury of the Tallinn main street project thought that my design would never be feasible because the white arches would hide a view of the old town – for me the arches are delicate. Design elements are discredited for hiding views, while to a greater or lesser degree, all the existing standard elements are more accepted, having become „invisible“.

Lately, you have co-authored some projects with Anna Mari Liivrand. What does collaboration with an artist provide?

A chance to discuss exhibitions – spatial experiences, topics, details. How visual configurations inform the surroundings. For the last four years, we have been designing the Tallinn Cruise Port Terminal with Maarja Kask and Ralf Lõoke. Both of us have won various competitions dealing with the harbour area, so this time we decided to collaborate. They also often travel across the world to experience different kinds of art and this provides a pretty good background for us where our different practices can meld into a joint endeavour.

Estonian architecture is lacking a more nuanced material sensitivity. The availability of materials was almost non-existent in the Soviet times, leaving this tradition quite barren. Our tradition of architecture is too thin for a material- or detail-sensitive thought, but it is slowly improving. For instance, all kinds of experimentation with timber; but in addition to private housing it should reach public urban buildings as well. Robustness can be pleasing as with Herzog de Meuron, but making a robust detail work requires just as much effort. I am very pleased with the robustness of the Võru square, the competition work even had a bit too smooth an appearance compared to the built result. Feedback from local citizens has been surprisingly positive. The theme of heritage often surfaces with public space projects. This even happened in Võru which is the youngest town in Estonia – I got a call earlier today, in fact, asking if it would be possible to add some traditional folk patterns. Yet, Marge Monko’s project from last year, “Artists in Collections“, displayed in Võru Museum, demonstrated how modern Võru citizens were already in the 1920s and 1930s. Historical quotes in urban space make me cautious. How do you organise a celebration on a square that is centred around a tomb? This almost happened in Võru because some politicians would have wanted the memorial to the victims of the „Estonia“ ferry disaster to remain in the middle of the square. Fortunately, they found a new place for the monument near the church.

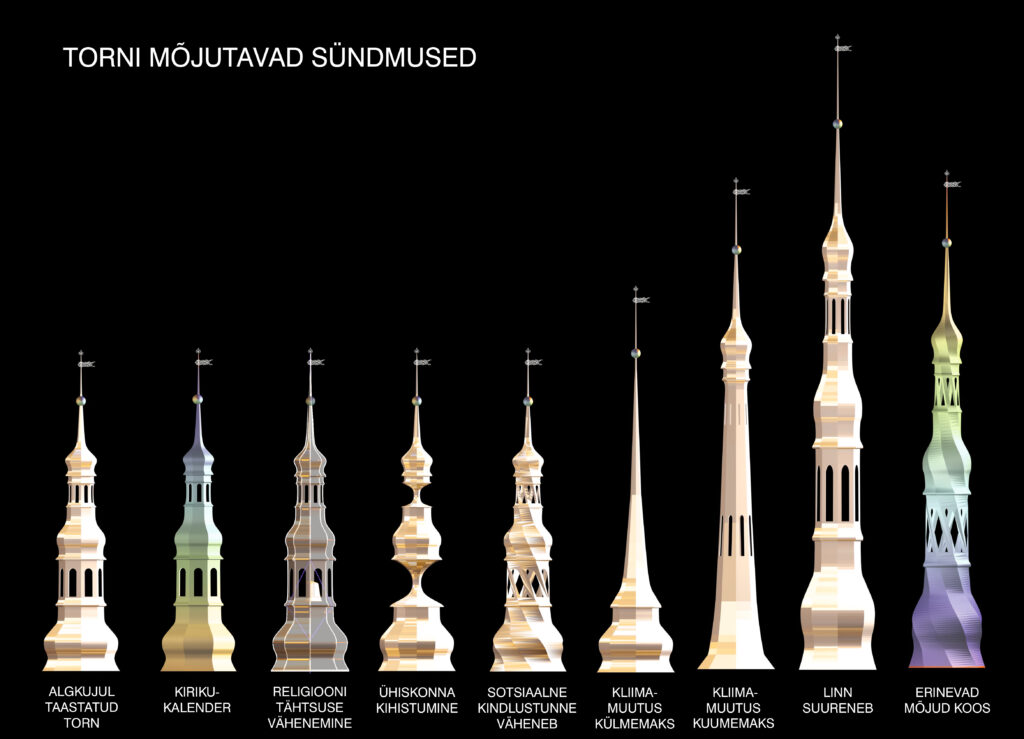

You have displayed quite a provocative spirit toward historical context sometimes. For example, the Holy Ghost Church tower project that reminds me of the recent debates around the fate of the roof of the Notre Dame in Paris. Mathieu Lehanneur proposed a tower form reminiscent of the flames of the fire, Studio Fuksas submitted a Baccarat crystal tower, Aleksandr Nerovnja – a roof made entirely of glass. Now, the ruling is in favour of restoring the original look. They are planning to rebuild the Glasgow School of Art in pseudo-form as well.

Right after the Notre Dame fire, the Minister of Culture declared that it will not be restored. Now, the tables seem to have turned, which is a shame. Why not complete the towers according to Viollet-le-Duc’s project then as well? The situation was similar with the Holy Ghost Church: what was left of the tower was below the minimum that is required by regulations of heritage conservation to restore the original shape.

I submitted a work entitled “The New Smokes of Town Hall“ to the Lift11 contest – the idea was to install smoke machines in the new chimneys of the freshly renovated Town Hall to restore the original vibe. Heritage conservation liked the idea, but the Madam of Town Hall was against – yes, that is an operating office.

Yet, you are one of the few Estonian architects who relates to the modernist architectural avant-garde such as the heritage of Le Corbusier. The courage to deal with not only the local Estonian context, but submit proposals to exhibitions concerned with the future of Paris or Venice – this is not all that common here.

Indeed, the apartment building on Pirita road was elevated to give room to the surrounding modernist park, and there is a garden on the rooftop. The interior solution is actually rather a comment on Moisei Ginzburg. Part of the apartments are situated on one side of the median corridor, part on the other, above and below. Externally, the Pirita building looks pretty robust, but the internal subject matter is actually quite delicate.

The Parisian project dealt with re-integrating the Champs-Élysées as a modern-day junk space in a way that would preserve the ceremonial potential of the street. In the space below the street, I designed a creative industry incubator that would function autonomically, with zero-energy consumption, zero-waste, and no need for imported food ingredients.

For this year’s Venice biennale competition we proposed a project focusing on life on the streets. This is something that has fascinated me on my travels for the past 15 years. In the name of hygiene, modernism effectively wiped out urban diversity – everyday life was segregated into monofuctional areas with transit corridors in between. As a result, pedestrian movement has almost disappeared and it is a major health risk for the urban dwellers. After all, man is a hunter-gatherer by evolution, meant to be constantly bustling around. The aim of the project is to find ways to bring the activities of gathering back to urban everyday.

You once wrote an article on how streets should have appointed directors, so that public space would be a matter of concern for somebody. Generating urban life among Nordic people is not all that simple. You envisioned a square curator in the competition project for Tartu New Market Square – a person to organise events, provide assistance, run a ping pong paddle rental, ensure “an ongoing street festival“.

Our park culture development is hindered by the belief that if you want to spend time in nature, you have to buy a summerhouse. This is extremely environment-hostile. People have two cars and two households.

There are many parks and green areas in Tallinn, but no consumers: life does not reach these areas. Deer Park is totally empty in the summer. At the same time, you hear a lot of talk about developing community spirit. The joint venture organised by Lasna Idea seems real, though, manageable for the citizens, intended not as a party for the whole city but serious local daily business.

Fortunately, we do not have only Estonians inhabiting Tallinn. Half are Russian and quite a large percentage are other nationalities as well. Parks are used by non-Estonians. Entering Narva, you see straight away that park culture is totally different. An unfortunate trend has radiated from shopping centres to public buildings, schools, apartment buildings – it is all about the atrium. The interior is staged as a pleasant atmosphere with open cafeterias and other functions but the latter could be used instead to integrate the building into the external environment, inviting people in from the streets who would otherwise never enter. The same applies to apartments buildings: stack pretty volumes on top of a modernist plate. An integrated street space is what you see in Rotermann apartment buildings, or the competition work for Pärnu 31 from a few years ago.

What is the status of the Kanut Garden Park project, and the Härjapea Journey?

The Kanut Garden Park project is at a standstill – at first they said it would continue after the completion of the first phase of the main street, but they lost interest and now we have a new mayor as well. The competition task was to join Pärnu and Narva roads with the harbour area by creating pedestrian-friendly streets perpendicular to the sea. I found it necessary to link the old town with the Rotermann Quarter and build Kanut Garden Park as an active space for the modern citizen.

The Härjapea competition was a vision contest. The river trajectory passes through a very versatile city space today, as it did in the past. The work built upon three topics: firstly, mobility enabling movement from one place to another; secondly, squares creating space and variation along the journey; thirdly, the gurgling of Härjapea River, i.e., the fountain-chain along the path that would resuscitate the river through sound. Current city plans are hopeful. I find joy in the making, that can’t be taken away by things left on hold, or undone.

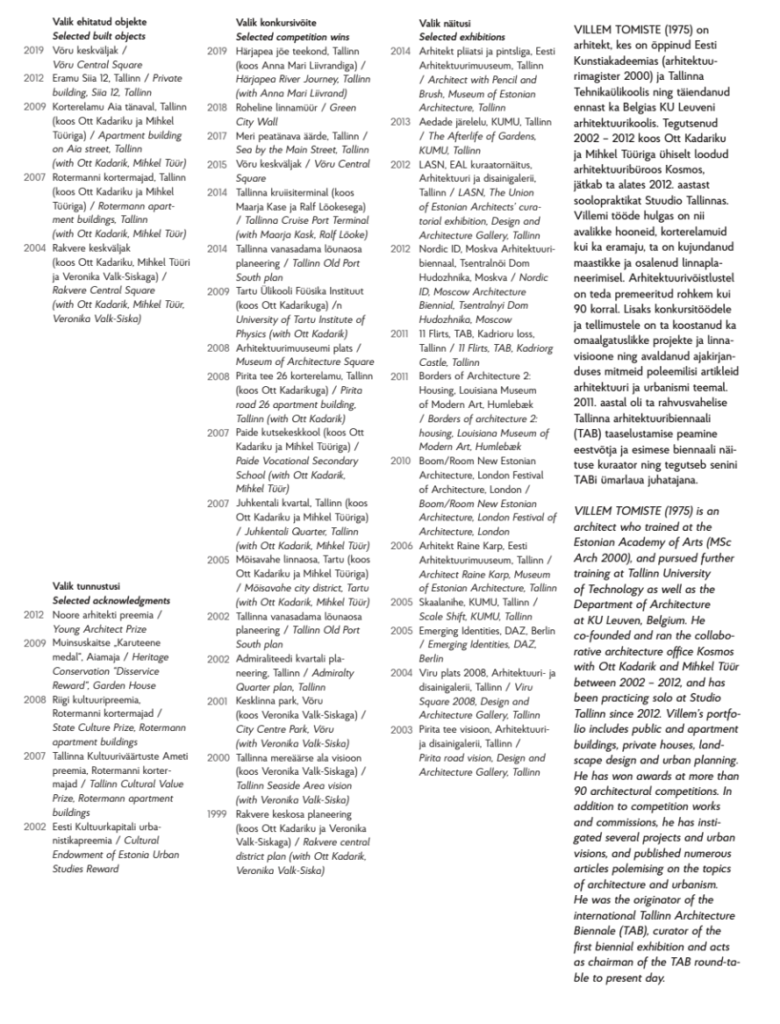

INGRID RUUDI is an architectural historian, critic and curator, junior researcher at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo by Renee Altrov

PUBLISHED: Maja 97 (summer 2019), with main topic Architecture is an Art of Space