The fate of a shrinking town is greatly influenced by the location and building of the state secondary school. In the course of the process of establishing twenty new state secondary schools, it is only natural to consider what contemporary pedagogy and the respective learning spaces are like.

We live in interesting times in school architecture. The establishment of new state secondary schools will introduce considerable changes in the present educational landscape and the physical school network. The present school network dates back to times when more than 21,000 children were born in a year. In comparison, only 14,000 children were born in 2016. Due to the rapid decrease of the number of students, more than a third of Estonian secondary schools now have less than 60 students.

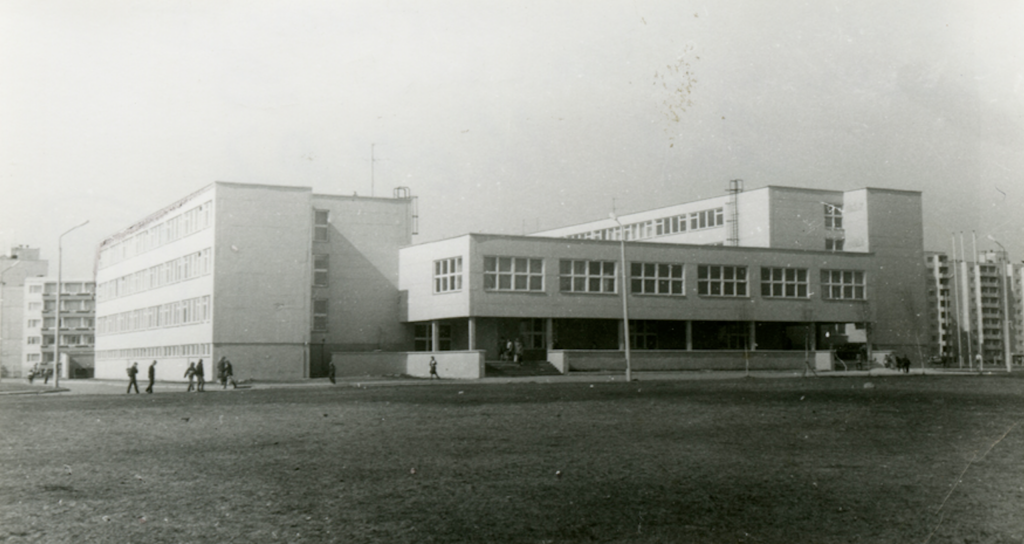

The programme initiated by the Ministry of Education and Research and executed by the State Real Estate Ltd (RKAS) to concentrate upper secondary schools in regional centres aims at improving the quality of education and ensuring a more effective use of maintenance resources. Such activity in constructing new school buildings was last seen in Estonia in 1970-1980s when all new pre-fabricated panel housing districts from Lasnamäe in Tallinn up to Männimäe in Viljandi and Vana-Vigala were studded with standard designs by the state design office Eesti Projekt. The most widely used design at the time was 221-1-321 by Milvi Vainik.

A School Building in a Shrinking Town

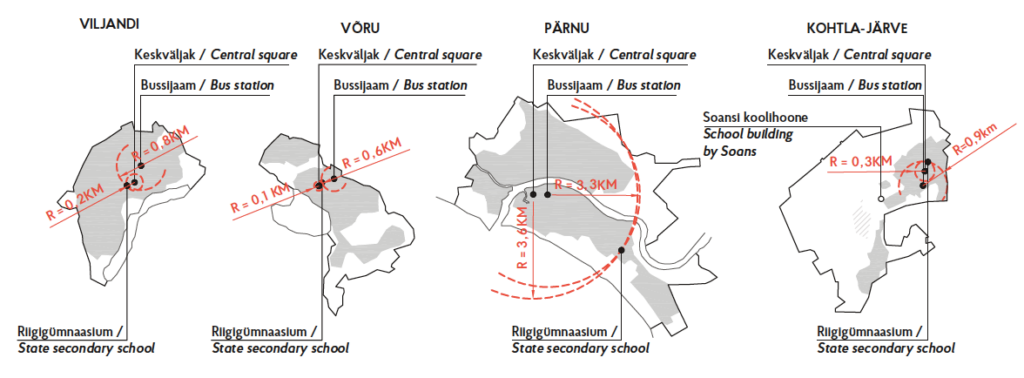

At the time of the construction of the given schools, the urban population was growing. With the number of people in most Estonian towns now decreasing, the location of the state secondary schools with a strong impact on the urban space must be carefully considered. Many small towns (Haapsalu, Kärdla, Valga, Viljandi, Võru) have established their state secondary schools in the centre thus enhancing the historic heart of the town. Beside the good examples, there is also the unfortunate decision by the town of Pärnu to establish their state secondary school in the 221-1-321 standard design building of Koidula Secondary School in the pre-fabricated panel housing area Mai about 3.5 kilometres from the centre. Although back then the given project was rather successfully adapted by architect Maie Hansmann, there are several historic school buildings in the city centre that with their stateliness and location could have provided considerably better options.

The state secondary schools are not meant to serve only the particular town but the whole county. It is thus important that the school be situated as close to the public transportation nodes as possible. The central bus station, however, is located in the city centre making it more difficult and time-consuming for the students from rural areas to reach the outskirts.

The architecture of the school building as the embodiment of the school identity and cohesion is similarly greatly underestimated. A vivid example here is the dispute concerning the expansion of Gustav Adolf Secondary School to the new building for the elementary and basic school level. For the given purpose, the former Vana-Kalamaja Adult Secondary School building completed in 1950s according to the standard project 2-02-27 was adapted and expanded. One of the main arguments of the opponents included the loss of the school’s history and identity stemming from the unique and dignified building despite the fact that the upper secondary school still remained in their historic building. Good teachers and students jointly form a strong community with its unique image, however, the state secondary school in Pärnu in its mass-produced body will never establish its own spatial identity as there are altogether 56 schools in Estonia cast in the same mould.

Unfortunately, a similar road with Pärnu was taken by Tartu with its new state secondary school also situated in a standard 221-1-321 type of a building in the outskirts of the city. However, architect Andres Kase has introduced some changes in the standard design and built a new wide recreational area with an outdoor lecture hall between the two wings. Also the new state secondary school in Kohtla-Järve has received some criticism. Differently from Tartu and Pärnu, the building will be in the current city centre. Given that Kohtla-Järve is one of the fastest shrinking towns in Estonia, it seems to be a clever move. The only misgiving here is that there is a school building designed by Anton Soans lying empty in the outskirts of the city that represents one of the very few architectural masterpieces in the area. There is no good solution to the problem, as according to forecasts, the population of Kohtla-Järve will drop from the present 35,000 to 26,000 by 2030. The historic school building designed for 522 students, however, is already at present too large for the new state secondary school with 252 students. Thus, the city government must seriously consider the best ways to make the urban space more compact and in all probability something needs to be sacrificed.

The citizens of Rakvere have been riled up by the new coalition’s decision to construct a new building for the state secondary school and reorganise the historic Rakvere secondary school building by Alar Kotli as a basic school. On the one hand, Rakvere must be credited with keeping also the new building in the city centre. On the other hand, it is debatable whether it should be located on the square in front of the present school. In case of Alar Kotli’s building, the urban void in front of the building is highly important as it allows one of the symbolic buildings of Estonian functionalism stand out in the urban space. The new school in front of it would clearly devalue the historic school building.

Then again, the yearning for a new construction is perfectly understandable as the present building with a classic layout does not correspond to the contemporary vision of a modern learning space. Similarly to the school designed by Anton Soans in Kohtla-Järve, the given building is protected heritage thus imposing strict restrictions for its renewed functions. The ideal solution here would be similar to the state secondary school in Viljandi, where the building under heritage protection was added a contemporary extension. As a result, the city has fewer buildings to maintain, the historic building retains its original function and there is also a modern learning environment to satisfy the needs of the students. In view of the demographic situation of Rakvere, it seems that they should perhaps consider closing the current school buildings instead of building a new one.

The Changing Learning Space

The new state secondary schools will have a strong impact on the structure of our towns, but there are considerable changes also within our schools. A vast majority of our schools have been constructed according to standard projects. They bear the mark of their time as they used to correspond to the needs and expectations of the society. The given schools are so-called shelf-type buildings with the classrooms piled upon one another on shelves and long connecting corridors in front of them. The latter were usually unfurnished maneges with the horses replaced with students walking in circles. However, it must be admitted that in the standard project number 221-1-321, the corridor extensions were also marked with the word “recreation”. In most schools, though, it only remained on paper. The canteen, library and great hall were separated and the access restricted.

In the new buildings completed or to be completed, the interior structure has undergone several changes. Comparing the new schools designed on the basis of public competition with those of the previous generation, there is an important shift in the interior structure. Namely, the school has evolved into an analogue of a small town with its central public square designed for people to eat, meet and spend their free time. The great hall, canteen and library – previously semi-public and mono-functional spaces – are now public areas with mixed functions. These are at the students’ service at all times. There is no traditional great hall. In the era of shrinking and converging, the waning of the great hall may be considered compellingly symbolic.

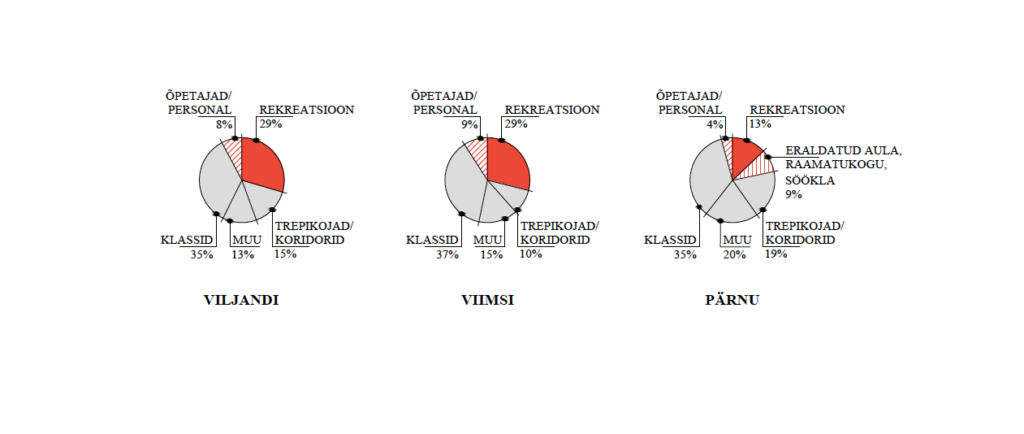

However, from the point of view of dance and drama clubs, the given solution is naturally quite unfortunate. There is no possibility to rehearse or pursue one’s hobbies in a more private environment that many children consider highly important. Then again, it is a good sign that in a country where every penny is counted, we have managed to open the classic closed spaces in order to expand the recreational area that functions as the school’s core with flexible functions. It becomes the great hall for more festive events and the hobby club area (for folk dance, for instance) after the lessons, while remaining a general recreational area at any other time. Such a solution may be somewhat inconvenient in terms of furniture, but at the same time provides the school’s spatial structure with much needed flexibility. In the earlier standard projects, recreational areas constituted 10-15% of the whole building. In the new state secondary schools, it has increased to 20-30% due to changes in the given spatial functions. Despite the various structural changes, the proportion of classrooms in the building has remained more or less the same, accounting for about one third of the surface area. The society is increasingly motivated by lifelong learning. People benefit from openness and quick adaptive skills. Interpersonal communication has a highly important role to play and the interior structure of the new secondary schools resembling town squares will certainly contribute to it. In addition to their regrettable location in the outskirts of the town, also the old-fashioned interior layout of the state secondary schools in Pärnu and Tartu remains utterly incomprehensible.

The discussions have mainly focussed on the appropriateness of school buildings for students, however, also the teachers’ working conditions would require further attention. As time goes by, people come to attribute increasingly more importance to their work environment along with their salary. Teachers’ rooms are generally similar to those twenty years ago. On the one hand, it is certainly the architects’ misjudgement, on the other hand, particular restrictions are set also by the school network programme by the Ministry of Education and Research stipulating that the net area of the whole building (from utility areas to classrooms and corridors) per student must be below 11.5 m² by 2020. Within the given area, it is virtually impossible to find additional space to improve the teachers’ work environment. At the same time, the selfsame restriction has also spurred the changes in the former structure of the great hall, library and canteen. In addition to the teachers’ lounge, the next school layouts set by the ministry should also include more private areas for students who wish to withdraw from the bustle of the town square.

Besides the proportion of various functions, also the spatial layout in the new schools has changed. For instance, there is no shooting range (which was not necessarily included in all schools earlier either) and there are new rooms for IT and counsellors as well as large lecture halls with a sloped floor. Also gyms are left out of most new state secondary schools. One of the key criteria in selecting the location for the state secondary school is the proximity of a sports centre. The aim is to promote cross-usage of the current structure of the city. The physical education classes will occupy the sports centres during the day when they would otherwise be largely empty. The given decision has been criticised, however, considering the tight budgets and shrinking county centres, it seems to be a reasonable solution.

Every child must feel that he is valued and worthy of investment. Also contemporary architecture must consider it. The standard designs 2E-02-2 and 221-1-321 were undoubtedly good projects at the time, however, the present school environment has changed. I’m glad to see that after the rocky start (with seemingly little comprehension of the wider impact of the decisions), the state secondary school process is heading towards improved spatial design with new spatial possibilities searched for the learning environments with architecture competitions. I can only hope that the process will not confine itself with the present achievements, but dears to experiment further and ask critical questions regarding the contemporary pedagogy and the respective learning spaces. The cornerstone of the given changes lies in public architecture competitions, while a highly important role is also played by school leaders and public officials with a vision and contributive power at the ministry and the State Real Estate company.

Architect ANDRO MÄND has participated in designing various educational institutions, including the state secondary schools in Viljandi and Rapla, he also works as a teacher in a secondary school.

COMMENTS

Kalle Komissarov, architect, coordinator of conditions for the state secondary school architecture competitions

The State Real Estate (RKAS), commissioned by the Ministry of Education and Research to organise the construction of state secondary schools, has so far coordinated the terms of the architecture competitions with the Union of Estonian Architects. The respective input, however, has been traditionally scant and concrete – the spatial programme by the ministry and the technical requirements for non-residential buildings by RKAS. Gathering information on the contemporary educational principles and the needs of the changing education system is the responsibility of the compiler of the competition brief. The Union of Estonian Architects has added some studies and websites to the competition terms: for instance, spatial solutions in support of movement, the effect of space on communication, and the space and time management of a school illustrated by the example of Viljandi state secondary school.

Looking back at the competitions so far, it is clear that RKAS has learned something new from every completed building with the acquired knowledge and solutions employed also in preparing for the next projects, however, it mostly concerns the technical aspects. For the architect, it stands for additional technical limitations restricting their creative freedom with every new project. There has been no such development in the concept and content of the input received from RKAS (concerning educational visions) and here perhaps the Union of Estonian Architects should give some good advice to the customer. Specialists of the ministry, the management of the future school as well as education specialists should be included in the process of drawing up the input and competition brief either on the initiative of or in cooperation with RKAS. The given step will allow them to improve also the underlying principles of school architecture.

State Secondary School Programme

Without architecture competitions

2013

Läänemaa Secondary School (reconstruction of the school under heritage protection)

Jõgevamaa Secondary School (reconstruction of the school building)

Nõo Secondary School (new building)

2015

Koidula Secondary School (reconstruction of the school building)

Võru Secondary School (reconstruction of the school under heritage protection with an extension)

Jõhvi Secondary School (new building)

Tartu Tamme Secondary School (reconstruction of the school building)

2016

Hiiumaa Secondary School (a new building for the demolished part of the building)

Valga Secondary School (reconstruction of the school under heritage protection)

Põlva Secondary School (a new nearly zero-energy building)

As a result of architecture competition

2013

Viljandi Secondary School

To be completed in 2018

Rapla Secondary School

Viimsi Secondary School

In the design stage

Kohtla-Järve Secondary School

Laagri Secondary School

Architecture competition in the following years

Kuressaare, Tabasalu, Narva, Rakvere, Tallinn, Paide

HEADER photo by Karli Luik

PUBLISHED: Maja 92 (winter 2018) with main topic Reasoned Shrinking