PROJECTS

Baltic Station Market. Aesthetics of Poverty 〉 Madli Maruste

Baltic Station Market: Interview With City Architect, Developer and Architect 〉Kaja Pae

Utopian Microcities 〉 Berk Vaher

Tallinn Old City Harbour Masterplan Competition 〉 Andres Sevtsuk

How to read the Masterplan Process 〉 Ülar Mark

PERSONAS

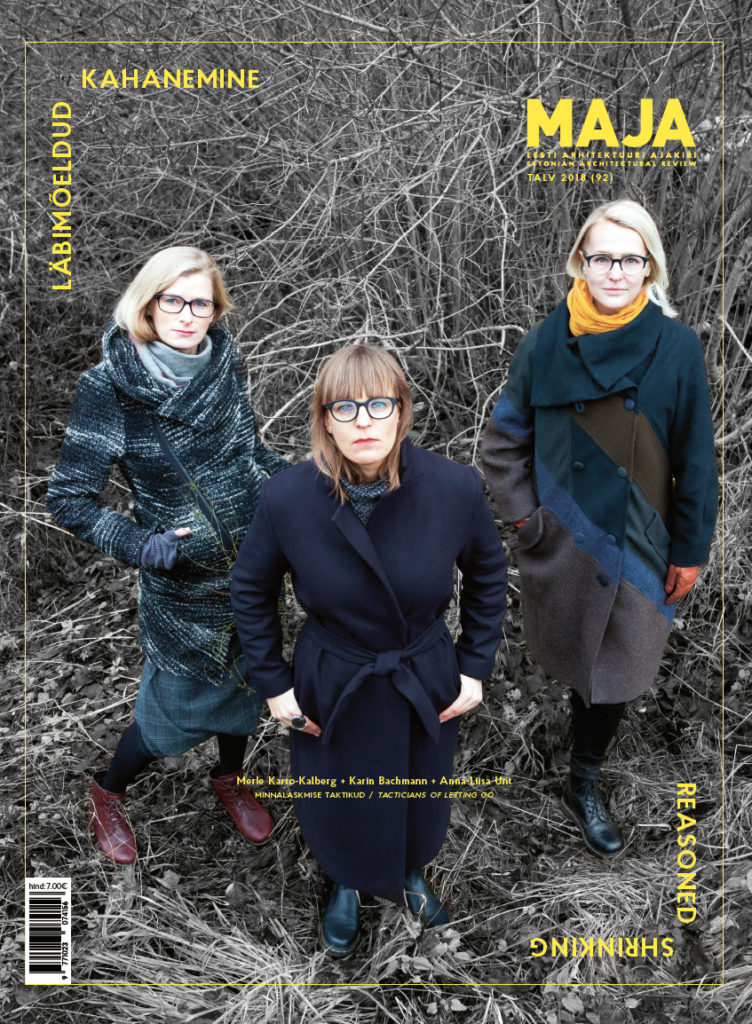

Tacticians of Letting Go. Landscape architects Karin Bachmann, Merle Karro-Kalberg, Anna-Liisa Unt 〉 Interviewed by Katrin Koov

REASONED SHRINKING

European Spatial Policies and State Architects 〉 Veronika Valk-Siska

Future of Estonian Settlements and Small Towns 〉 Garri Raagmaa

Administrative Reform and Spatial Planning 〉 Tiit Oidjärv

Comprehensive Planning After Administrative Reform 〉 Pille Metspalu

The Many Faces of the State Upper Secondary School Programme 〉 Andro Mänd

How to Protect a Shrinking City? 〉 Jiri Tintera

Narvaaaaa! 〉 Friedrich Kuhlmann

Coastal Cultural Spaces 〉 Eva-Liisa Lepik

Abandoned Sanctuaries 〉 Eva Kedeauk

Curating Shrinking 〉 Mark Grimitliht

THE GREAT BEAUTY OF SHRINKING

In autumn, the EU Architectural Policies Conference took place in Tallinn within the framework of the Estonian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. The speakers including both state architects, promoters of architecture and practicing architects provided a balanced discussion on the future of European architecture. The conference came to assert that the word ‘architecture’ in the titles of national architectural policies has gradually been replaced by ‘place-making’ or ‘designed environment’ thus providing a more adequate picture of the scope of the work of architects. In the present issue, an overview of the work of European state and government architects is given by Veronika Valk-Siska.

An effective, albeit perhaps slightly exaggerated image of the scope of spatial design is provided by the concept of ‘hyperobject’ by philosopher Timothy Morton. He used the term when speaking, for instance, about the climate crisis as, on the one hand, it is revealed on various scales while, on the other hand, it is difficult to grasp as a comprehensive whole. The overall effect of the decisions concerning space are somewhat comparable. The Flemish government architect Leo Van Broeck characterised it by saying, “Local actions require global thinking”, and his office, for instance, does not support the construction of private houses but only apartment buildings. “One of the greatest challenges for spatial design is the increasing number of people, that is, there are too many of us on this planet,” Broeck said. When leaving the conference hall, my friend stated that perhaps there is something that we do right in Estonia … we shrink.

Indeed, almost all Estonian towns are shrinking. In the past 27 years, the population of (all) Estonian towns has decreased by 5-62%. At present, only the urban regions of Tallinn and Tartu are growing. The awareness of decreasing population and its consideration in spatial design does not stand for letting go, instead it may help us to find new values despite the highly meagre resources.

The national spatial plan “Eesti 2030+” dating back to 2010 aims at maintaining the present housing structure with the key to the survival of small towns lying in their improved connection with larger cities. Garri Raagmaa, Tiit Oidjärv and Pille Metspalu study how many of the ideals of the national spatial plan are implemented and if the latest major change – administrative reform – supports its objectives. The state of shrinking requires highly comprehensive consideration of the use of resources and the impact of the state measures without losing sight of the main goal. The various effects of the state secondary school programme, including the importance of the location of the school building for the town is discussed by Andro Mänd. The state architect of Valga Jiri Tintera talks about the issues arising in a shrinking town with regard to national heritage.

The Creative Cities – Telliskivi in Tallinn and the Widget Factory in Tartu – are examples of the surprising effects of old spaces provided with new functions. The utopian potential of the given districts is weighed by Berk Vaher. We will consider the extent to which the new Baltic Station Market has managed to maintain the air of the old market and the community of traders as well as its architectural essence from the point of view of a user, city architect, developer and architect.

The feature article focuses on the first generation of landscape architects from the University of Life Sciences, the proponents of high-quality thicket Karin Bachmann, Merle Karro-Kalberg and Anna-Liisa Unt who have acted as a trio extending the boundaries of landscape architecture and underscoring the value of naturalness.

While the regional centres were tackling the challenge of finding new functions for deteriorating historic buildings, the emotionally charged Old City Harbour masterplan competition was concluded in Tallinn which in terms of square meters will establish an urban area of the size of a small Estonian town. The entries of the final stage and the subsequent discussion are analysed by Andres Sevtsuk and a member of the jury Ülar Mark. In the winds of abundant change, the city centre seafront of Tallinn provides a textbook example of the need for the institution of the state architect also in Estonia. In order to prevent the great forces from nullifying each other in a head-on clash, there is an urgent need for an institution to coordinate the activities of the various parties in a situation of strategic importance for the whole state and to help to comprehend the wider consequences of various spatial decisions.

Kaja Pae, Editor-in-chief

January, 2018