Interview

The aim of the council of the foundation is to acknowledge and support primarily architects and groups of architects who have veered off mainstream architecture. Why did you set such a goal?

Kristel Ausing: Brothers Hanno and Erki Kreis, who gave impetus to the foundation, were both that kind of creators with their own unique view of the world and preference for alternative routes.

Emil Urbel: We were more friends with the younger brother Hanno Kreis. Veering off the mainstream was his attitude and way of life. I remember when we were hitchhiking in the vast expanses of the Soviet Union, Hanno said that you should never queue for tickets, you should always go the counter for the military to buy your ticket. This he applied also elsewhere, as he was never satisfied and always tried to find a different route. Some things he never completed, but he gave a new perspective to ideas that others would not have thought of. This is how we were led to the idea that the foundation should acknowledge that kind of an attitude.

Mart Kalm: Today there are countless clichés on good architecture and the right ways to do it. I like the fact that the Kreis Foundation Award has called the traditional value or cliché on exemplary architecture into question. That kind of successful architecture would have been difficult to execute in their days which was largely spent during the Soviet era. The cliché was not that powerful at the time. In the current capitalist commercial world, the successful architect is considered highly important. Our award, on the other hand, is meant for a searching soul deviating from the mainstream. It hasn’t been a pressing problem in the past few years, but at first we sometimes said among ourselves that we wouldn’t mind if we had to give the award to Lubi Vaike. She was a so-to-speak nutcase who lived near Suure-Jaani, sometimes called a people’s architect who built a giant tower out of random sticks and twigs for herself in the 1980s.

Emil Urbel: There is now a similarly curious character Jaan Alliksoo in Hiiumaa. He built an Eiffel Tower out of sticks that became a local attraction.

Mart Kalm: I believe we need to make a clear difference here. Such alternative architecture is sometimes done simply for attention. Lubi Vaike did not want to become famous with her creation, instead, she was inspired by her curious view of the world and inner need.

Kristel Ausing: A picture of Lubi Vaike’s tower is still featured at the background of the Kreis Foundation Award diploma.

Why is it important to notice and distinguish people and activities veering off the mainstream?

Emil Urbel: First of all, we should ask what the mainstream is. Built architecture has become rather primitive. All new buildings are identical: posts, boards and something around them. Whether it is a bit this way or that, who cares. This makes us look for something different. It is increasingly difficult to find such an idea. The market and money set their own rules. There is a considerable pressure to make money and be successful, even to run an office. The given model does not encourage you to think differently. But who will pay for the innovation or divergence in thinking? There are few left who attempt to be different and do differently.

Kristel Ausing: The range where it works out great is very narrow. The divergence in thinking and action can also work out poorly.

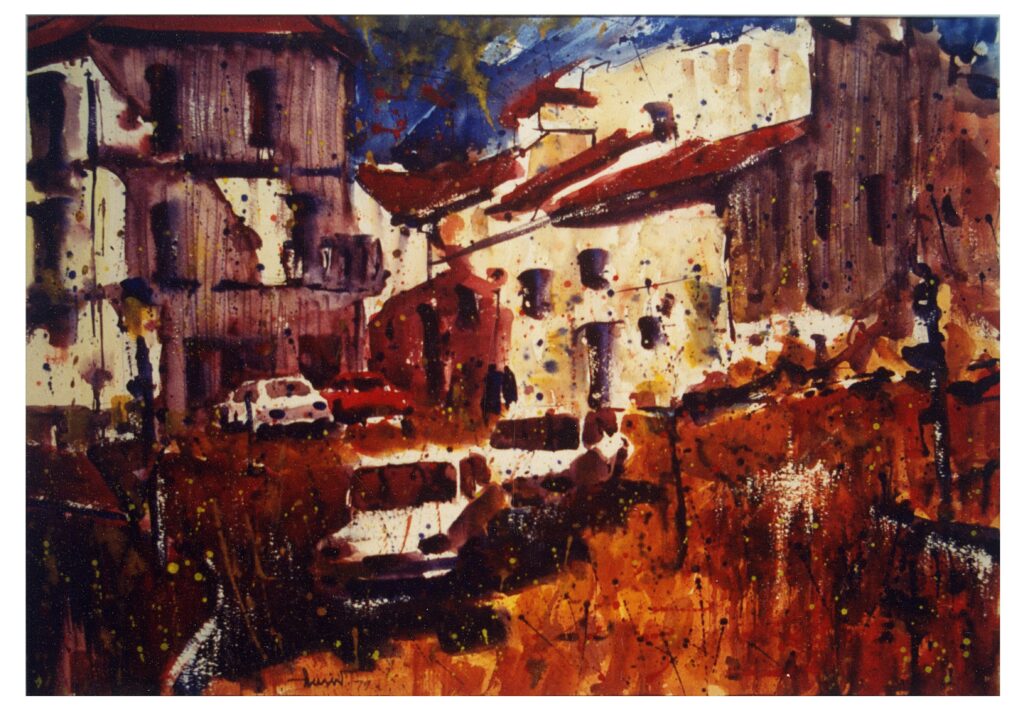

Emil Urbel: We haven’t written it down, but we have agreed that the dissenting idea that we will recognise must also be executed well. We have awarded also highly renowned authors, such as Toomas Rein. He caught our attention as he is not only a very good architect but also an artist, watercolourist and lecturer.

Mart Kalm: I believe it is important to consider architecture as a discipline in somewhat wider terms. Architecture is not restricted to the practice of a qualified person in organising space. It is an intellectual activity. The given field is considerably more extensive than the mere practical mainstream, that is, what is done by the majority. It would not be right to say that we have poor architecture competition juries who have awarded so-to-speak wrong achievements. Indrek Peil and Siiri Vallner from Kavakava office are definitely among the most original practitioners today and certainly not mainstream. They have nevertheless done very well, received numerous important commissions, won architecture competitions and awards. They are curious and strange enough to solve spaces differently, but our general progressive awards have taken them to the top already so that there has been no need to acknowledge them with the Kreis Foundation Award. We have rather searched for those who have been left aside.

What does the jury’s work look like? The competition is announced every year in the trade association list and the media. What is the proportion of proposals made by the general public and to what extent is the foundation responsible for finding the appropriate award winners?

Mart Kalm: We have got a huge number of good ideas from the open call. Considering all the excessively long and thorough jury discussions, I dare say that around half of the nominees have been harvested from the public call and the other half have been found by ourselves.

Kristel Ausing: There are also nominees who have been discussed on several occasions at our meetings over the years and are constantly shifting upwards. We probe into those aspects of each candidate that make them differ from the mainstream.

Mart Kalm: There have also been candidates who have not been selected for some reason or another, but they apply again in the following years.

Emil Urbel: The topics raised around us change constantly and occasionally time has been on some candidate’s side. After all, we also attempt to contribute to spatial politics with the award, highlight the aspects that are important for us or that others may not notice or do not wish to notice.

Mart Kalm: I believe that we have played a considerable role in shaping the mainstream. After we awarded the Czech-born city architect of Valga Jiří Tintěra, he came to receive also more general acknowledgment. For instance, it is primarily based on his idea that the team led by Kalle Vellevoog won this year’s competition for the Estonian pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Tintěra has naturally been highly active himself too, but I believe that we have contributed to his journey to Venice.

What is your understanding of the mainstream? Could you name any criteria or aspects to characterise the mainstream?

Mart Kalm: We have not set any clear principles. That would be a tad too complex. Instead, when considering every candidate, we have thought if their works are mainstream or not.

Kristel Ausing, Yes, in every specific case we have considered if the candidate’s works include interesting offshoots.

Emil Urbel: Is Frank Gehry a mainstream architect? How would it be possible to define the mainstream? For us, it is important to find a person who does something important or idiosyncratic: focusses on religion or does something that others don’t want to or cannot do and don’t have the patience for.

Mart Kalm: We are now used to the fact that Katrin Koov is the president of the Estonian Association of Architects. But with Kreis Foundation Award we wanted to highlight her alternative landscape designs.

What are the jury’s discussions like?

Kristel Ausing: They are very long and emotional. It is highly interesting for us as well as we often work out many things.

Emil Urbel: It also happens quite often that the candidate initially expected to get the award is discarded and the award is given to someone who we would not have even considered at first. We argue a lot but we always make a unanimous decision. We have never voted.

Mart Kalm: Searching for the different routes takes quite a lot of time. However, it is important that there is good architecture also outside the cities where money is naturally accumulated anyway. For instance, a few years ago, we acknowledged Ülevi Eljand’s achievements as the town architect of Võru and Valga. He was also a renowned artist when he went to school in 1970s. He has been similarly acknowledged by Kumu and young art historians. He has become a composed town architect fighting for high-quality space in “depressing small towns”.

Emil Urbel: He is the salt of the earth in the best sense of the word whose mission is to export architecture to small towns.

Mart Kalm: We acknowledged Andres Põime for his persistence in holding the classic Nordic Modernist line while many other architects turned their back on such a mindset due to fashion or circumstances. He has had the confidence to remain true to his vision.

Emil Urbel: In his case, it is also important to highlight the dimension of regionality. He has established good cooperation with the former A&O, the present Coop supermarkets in South-Estonia. He has done many things that do not qualify as the classic show architecture and thus the architectural quality and meticulous details often remain unnoticed.

The winners have mostly been architects with one exception. In addition to architects, there is also Ingrid Ruudi who is actually an art historian. How did you find her?

Mart Kalm: With the exhibition “Unbuilt. Visions for a New Society 1986-1994” (Ehitamata. Visioonid uuest ühiskonnast 1986–1994) she brought completely new topics to architectural research that had not been explored before. At the time, history writing had not quite digested it yet. Her approach was exciting and contemporary. Today, architecture is mostly discussed through design aspects in home décor magazines. It is not wrong or bad as such but there is no serious perspective to architecture. We have not had deep and intellectual exploration of architecture and this is where Ingrid Ruudi comes in.

Emil Urbel: The given exhibition touched me deeply and also the representatives of our generation in the foundation. I suppose this had some impact, but I must stress again that the most important role is played by quality.

It seems to me that the winners of Kreis Foundation Award are creative minds who have mastered the mainstream but can easily also go against the tide. Toomas Rein seems to have the status of a classic. Others have also received various smaller and major awards.

Kristel Ausing: True, we haven’t really explored the completely uncharted territories.

Mart Kalm: Well, we have of course considered who has received awards earlier, however, there are now various new prizes and we don’t really want to nitpick. I believe it is also important how we perceive the person’s presence: who is more friendly with the media, whose buildings tend to get more coverage. The public image is not always related with quality. Photogenic buildings stand out more but it does not automatically mean that the space has better quality.

In addition to the alternative routes to the mainstream, we have also considered it important to highlight architecture that has been left aside or remained unnoticed. Total alternative has never been our strict goal. Ethical attitudes neither.

Kristel Ausing: Instead, we want to acknowledge a creator who is good at his or her daily work but also has something extra, an additional nuance.

Emil Urbel: Similarly, we value a quality that has been left unnoticed or that nobody has known how to distinguish. Of course, we will not award any random amateur from the periphery. We do not seek curiosities, the works of the award winner must correspond to our current life, ethical convictions and contemporary thought.

MERLE KARRO-KALBERG is a landscape architect and the editor of architecture of the cultural weekly Sirp.

Marika Lõoke

Already in the 1970s and 80s, Marika Lõoke stood out while working at EKE Projekt. Several buildings, such as the Recreation Centre for the Council of Ministers in Narva-Jõesuu, as well as buildings for Võru and Saare KEK were built in this period. After years of neglect, the listed building for Saare KEK on a roundabout in Kuressaare, has gradually been renovated by the local entrepreneur Helle Susi. Unquestionably, this is a tribute to the work of Marika Lõoke.

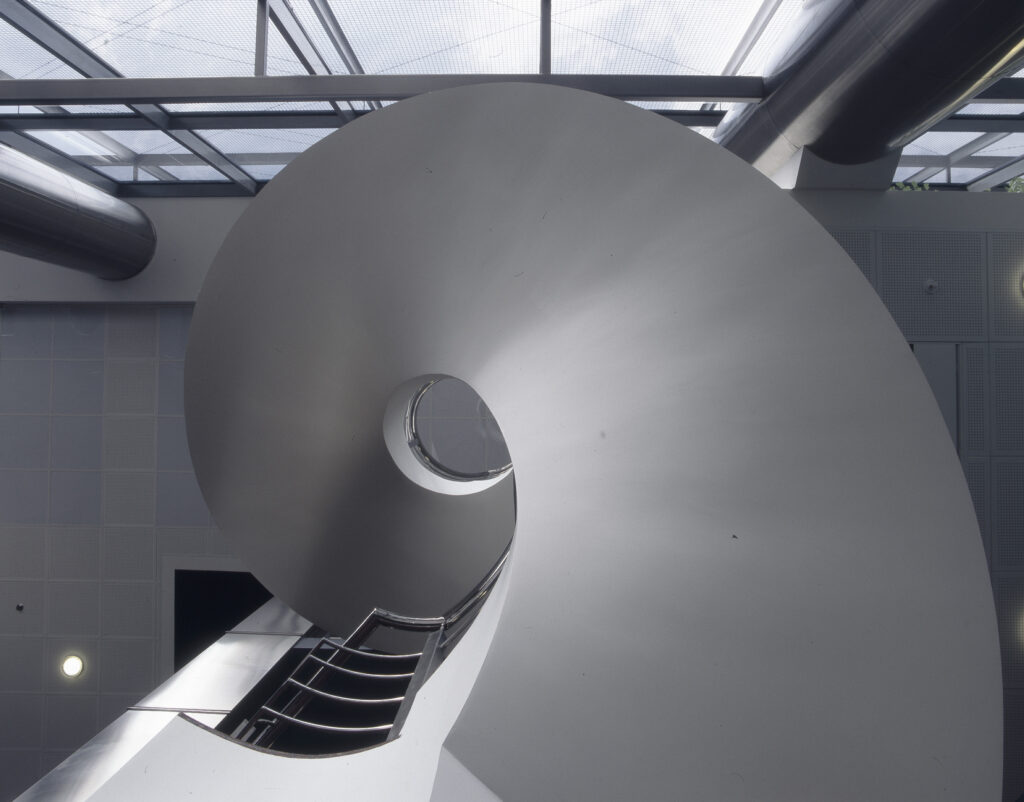

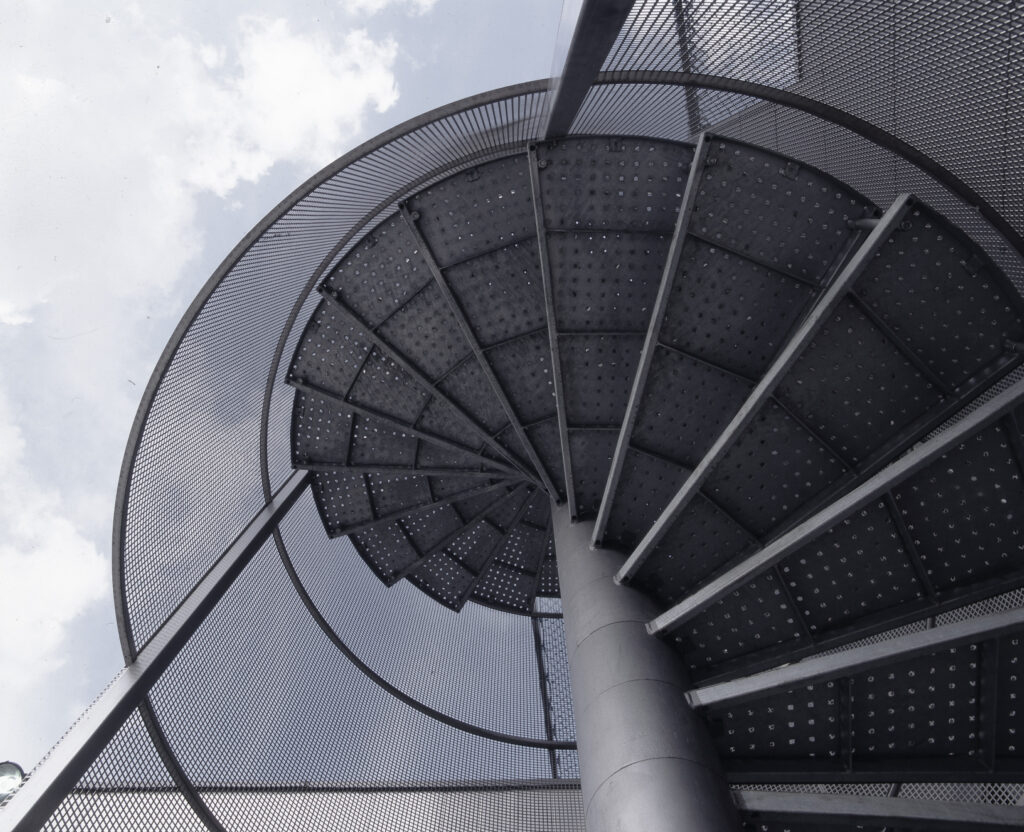

After the Estonian Restoration of Independence, together with the artist and architect Jüri Okas, Marika founded a successful architectural office. Over the last decades, they have designed rigorously laconic office and housing projects, that stand in sharp contrast to the flashy trends of the mainstream.

What makes Marika Lõoke prominent and particularly prizeworthy is her contribution to the work of the Estonian Association of Architects and the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, as well as her contribution to the organisation of architecture competitions. She is one of the most frequent members of competition juries, and uncompromisingly insists on high quality architecture.

Mart Kalm, the chairman of the Kreis Family Foundation who awarded the prize to Lõoke, finds that her service to the public by firmly standing for high quality architecture amidst the pressures of developers, weak local councils and submissible colleagues is rare and it has not been appreciated enough until now.

HEADER: Chairman of the Kreis family Foundation board professor Mart Kalm and the 2019 laureate Marika Lõoke with a diploma. Photo by Aleksander Siim

PUBLISHED: Maja 98 (autumn 2019) with main topic Author