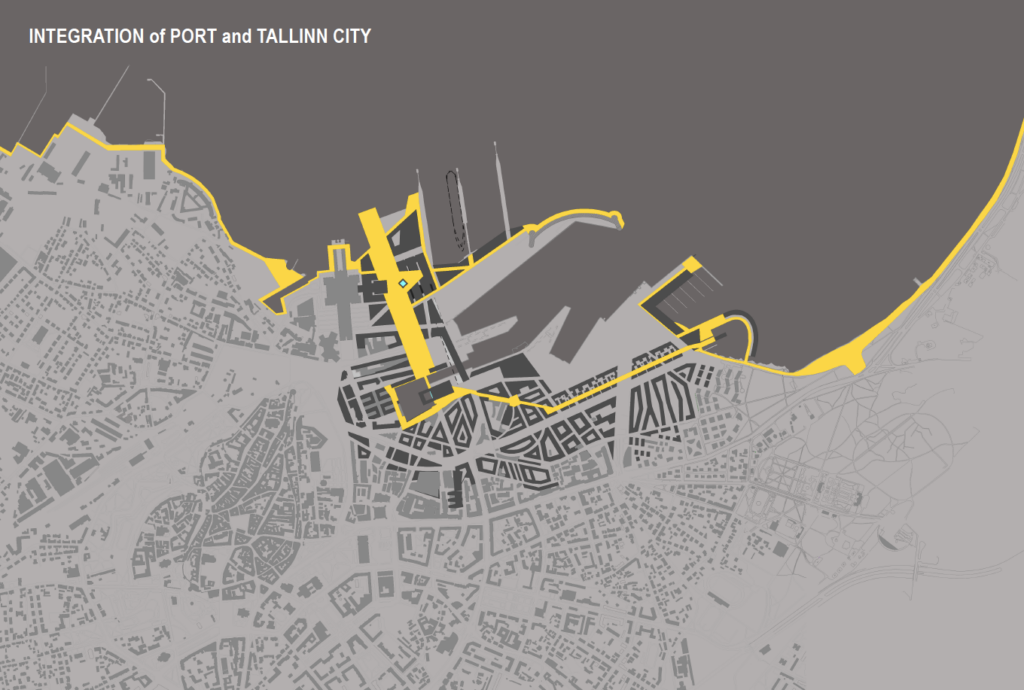

The main challenge for the competition lay in connecting the harbour with the city centre and creating a built environment that would speak to all Tallinners.

The results of the three-stage invited competition for the Tallinn Old City Harbour (Vanasadam) were recently announced. The competition dealt with a complex urban area, which had long been closed to the public due to its industrial history and functional harbour1. Participants were expected to propose solutions, where a considerable area owned by the Port of Tallinn would be urbanistically redeveloped. Keeping with the mandate of the Port of Tallinn as a state enterprise, serving public interests, participants faced the challenge of connecting future developments public spaces in the harbour with the existing city centre, North Tallinn district and Kadriorg districts that surround the port.

The three finalists included Alver Architects and Douglas Gordon, Kavakava OÜ with Alejandro Zera-Polo and Zaha Hadid Architects. Zaha Hadid Architects were announced as the winners in September 2017.

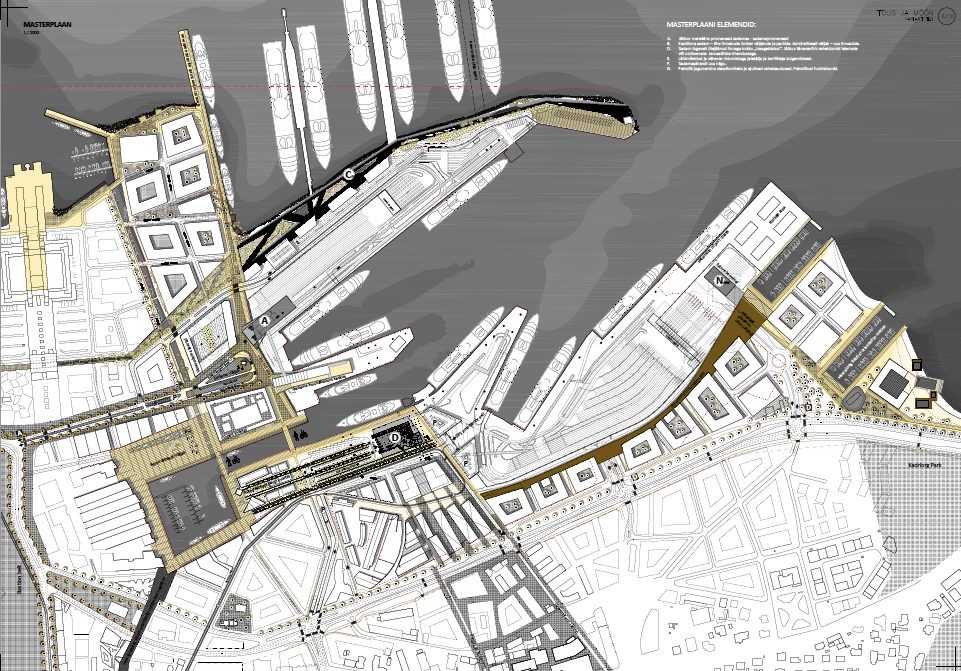

Zaha Hadid Architects

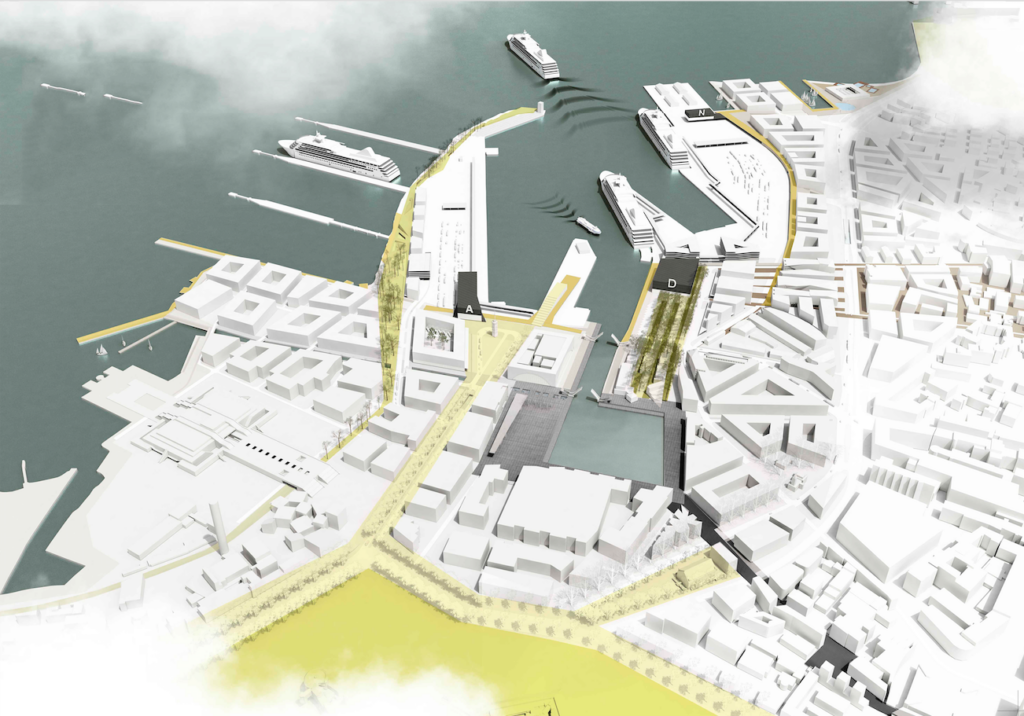

The ZHA proposal included a set of interesting ideas, but also qualities that are inappropriate for the Tallinn city centre. On the positive site, the team proposed to redevelop the current port terminals A/B and D as new, 21st century facilities, forming key landmarks in the city centre. Almost 10 million passengers arrive in Tallinn every year through the port – significantly more than the airport and railway station combined. The present cruise ship area behind Terminal A was proposed as open to the public, accommodating a park that would considerably extend the public waterfront. The pier behind Terminal A is currently closed to the public, yet cruise ships only arrive at its northern side during summer months.

The entry by ZHA also produces several qualities that are ill suited to the Tallinn city centre. The suggested building fabric is strikingly different from surrounding areas and would not establish natural connections with Kalamaja, Kadriorg and the city centre. Planned building volumes are excessively large, many of them comparable, for instance, to the size of Teenindusmaja (present Tallink Hotel) near the Viru Centre. Almost the whole development is composed of large, free-standing buildings that do not form continuous wall-to-wall street fronts. Such formal separation from the rest of the city centre would result in the harbour as a natural extension of the city centre, it would instead continue to emphasize its separation.

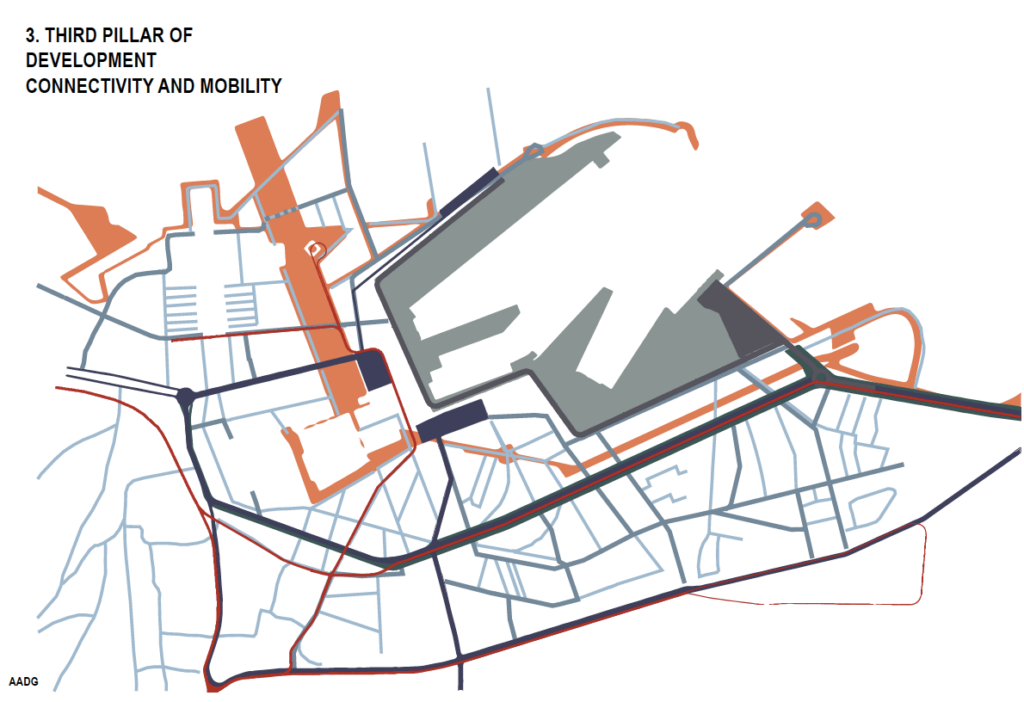

A key element in ZHA’s entry is the pedestrian promenade – called the Stream – that runs from Kadriorg to the harbour, starting parallel to (an competing with) Reidi Road between new buildings, then connecting diagonally over the Admiralty basin and dissolving by the waterfront between the City Hall and the cruise ship area. The promenade is proposed as the focal point of the public space with most of the proposed buildings oriented towards it, somewhat similar to the High Line in New York City. In my opinion, however, this pedestrian spine emphasizes movement in the wrong direction. Longitudinal waterfront paths from Pirita to the harbour are mostly used by joggers and recreational walkers. The development of the harbour should instead focus on the connections with the surrounding districts of Kalamaja, city centre and Kadriorg. These critical urban connections have unfortunately not been sufficiently addressed. In a similar manner, there has been no attempt to improve the currently problematic roads and traffic intersections along Reidi Road, Mere Avenue and Ahtri Street, which presently separating the harbour from the city centre.

Near Kadriorg and the present Terminal A, the proposed promenade rises to a second-floor level, leaving the ground level for road traffic and parking entrances. Considering the housing density of Tallinn, such a multi-level solution would likely introduce a number of problems. The upper level could remain poorly utilized, much like the current roof deck of the City Hall. The multi-layered solution would most probably have to be constructed by private developers, not the city government, which threatens to give the promenade a private character. Furthermore, if the peninsula behind Terminal A would ever open up for redevelopment, concentrating the harbour activities entirely behind Terminal D, an elevated promenade and partially sunken road behind City Hall would create a visual and physical barrier between Kalamaja and the current Terminal A loading area. It would be preferable to establish a well-connected, ground-level street network around the harbour, which should seamlessly connect the area with surroundings built-out districts, creating ample public opportunities to move to and through the harbour district in all directions.

Also in terms of land uses and functional programming, the ZHA proposal feels elitist and clearly incongruent with the surrounding city centre. The suggested programme mostly includes class A office space, luxurious flats and serviced apartments. An explanatory note suggests that “locals are drawn to the area by the promenade, marinas and spas”. But how many Tallinners visit spas or go yachting?

ZHA’s proposal clearly addresses the interest of the Port Authority and the tourists, but it fails to adequately address the interests of the residents of Tallinn. The project does not sufficiently reflect the morphological, social and historic context of the city centre and would likely create a spatially separated, heavily privatized and elitist waterfront.

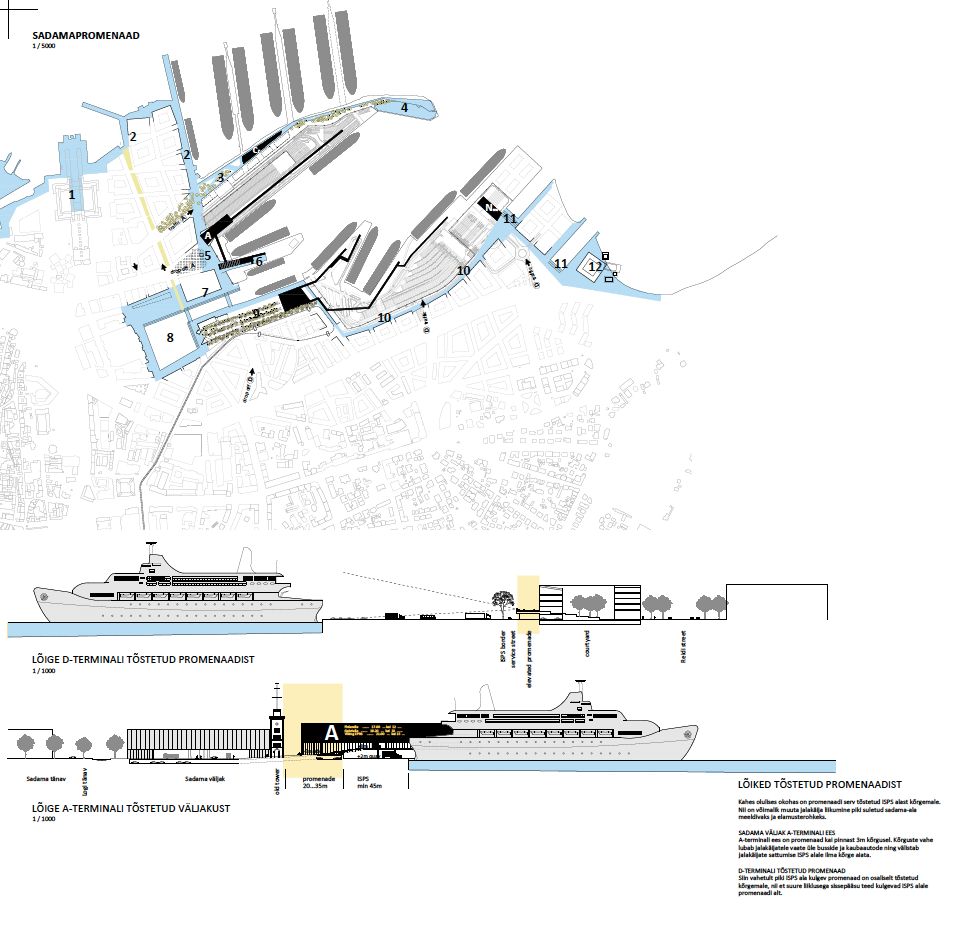

Kavakava

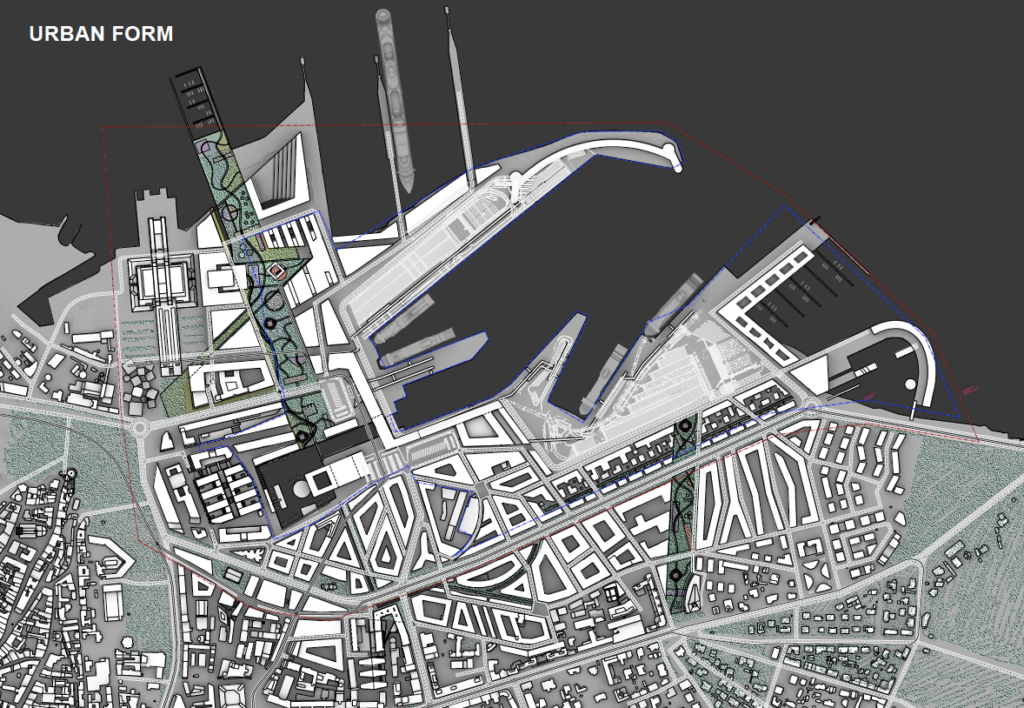

There are many positive features in Kavakava’s proposal. The solution stood out from other entries for its sensitivity to historic context. It emphasizes historic streets and directions that connect the harbour with the surrounding city centre. Sadama Street as the oldest street between the present port and the Old Town is renovated along with a preserved tower in the harbour headquarters building. Near Kadriorg, at the site of the first swimming pavilions in the 19th century, a beach is restored together with a new sauna complex. Reminiscent of the first half of the 20th century, railway trajectories are implemented as paving design elements. From more recent history, the project retains the large and distinctive concrete slabs and a decommissioned derrick crane at the tip of the peninsula behind Terminal A.

Landscaping and green areas have been carefully considered. An attractive square sheltered by pine trees is proposed in front of Terminal D, which would invite visitors to walk to the old town. Anther square is proposed in front of Terminal A. The Merchants’ pier between the terminals is conceived as a public area, moving the vessels that currently dock there to other piers. In its place, a public building with a stepping terraced roof is proposed, providing magnificent views of the old town. This would be a welcoming solution, which would significantly extent the present public waterfront from the Admiralty basin to the sea.

Kavakava’s proposal creates a number of new streets and street fronts between party-wall buildings. There are two parallel bridges over the Admiralty basin, extending Paadi and Laeva Streets and providing good connections to the northern districts, which would otherwise be cut-off by the City Hall. In terms of land use mix, the proposal expands Tallinn University’s campus towards the harbour, which would bring students to the area, contributing to the site’s vibrancy and diversity on a daily basis.

A few shortcomings should also be mentioned. Three adjacent squares around the Admiralty basin seem a bit excessive. Instead, the immediate surroundings of the basin could perhaps have denser construction, ensuring that the area is visited not only by tourists but also the locals. A ten-meter wide sidewalk on the northern side of the basin could function as a modern analogue to the famous Nyhavn in Copenhagen.

The tramline is unfortunately proposed only to Terminal D, without continuing over the Admiralty basin. There is no connection to Terminal A, the cruise ship area behind it, or to the new residential district behind the City Hall. A tram extension in that direction would be an easy way to bring life to the northern area that is difficult to access. It would also help cruise ship passengers reach the city by public transport.

An elevated pedestrian promenade is proposed parallel to Reidi Road, along the fence that overlooks the harbour. Similar to ZHA’s proposal, a need for such a two-level circulation system is questionable.

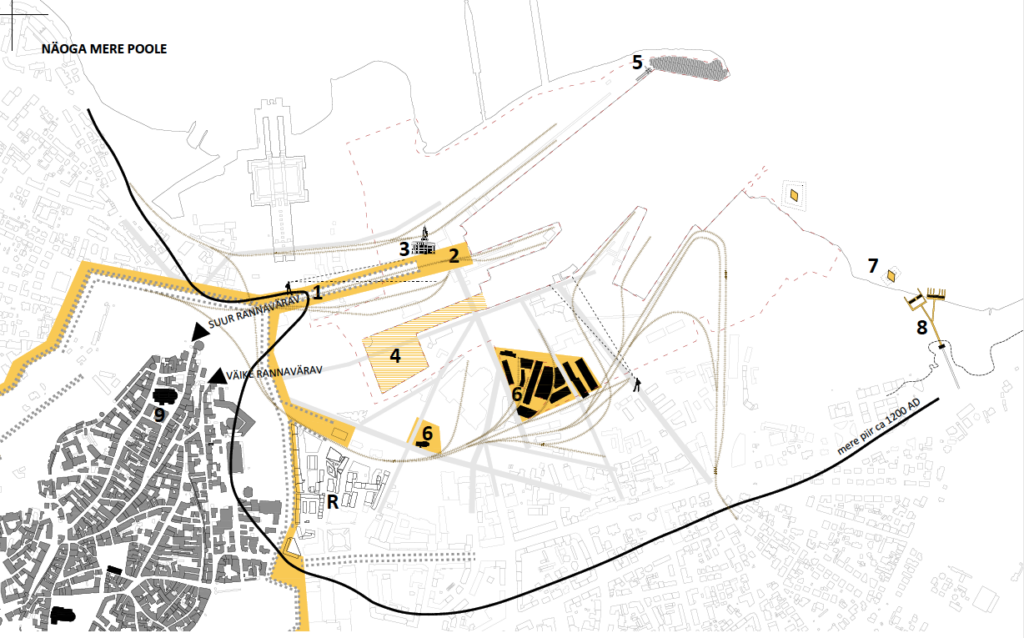

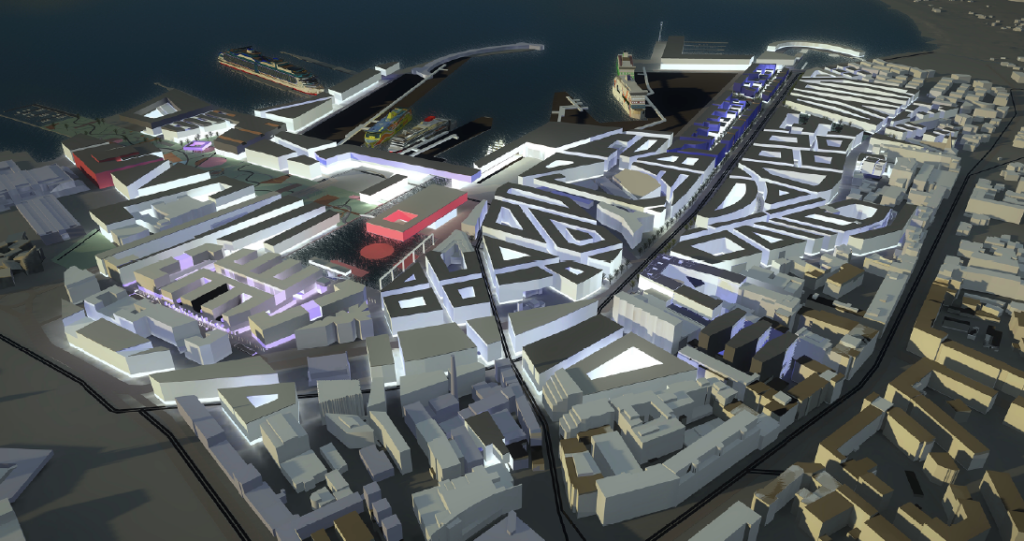

Alver Architects and Douglas Gordon

Alver Architects’ solution also includes a number of bold ideas that would be suitable for Tallinn. The team has carefully considered how to connect the future harbour with surrounding areas. Instead of the present Reidi Road design, a prominent avenue has been proposed, with more urban four-way junctions that eliminate the wide turning radii for lorries. The road is narrower and the buildings are closer to the street than in the current city proposal, thus creating active commercial premises along wide sidewalks. Traffic on Ahtri Street, which at present contains a split roadway, is proposed as concentrated on the northern side. This would allow the present Rotermanni Quarter to be extended towards the harbour, creating a better connection between the waterfront and the city centre. The proposed Redid Rd solution merits further development in cooperation with the city.

Alver Architects have also proposed a tram network that would well connect the present Terminals A and D as well as the cruise ship area behind City Hall around it. This line could work with a seasonal schedule given that cruise ships only arrive in the summer. An opera house is proposed behind the City Hall to bring new life to northern districts.

Considering climate change and sea level rise, all new construction in the harbour area is proposed at a base height of 3 metres above sea level. This is a forward-looking approach that merits consideration for all waterfront developments in Tallinn. The guidelines for such a policy should be drawn up either by the city or the Ministry of Environment.

Standing separately at present, Alver’s proposal sees Terminals A and D as connected into a single terminal in the future. This is an interesting idea worth further consideration. With a joint terminal, maintenance costs could be reduced and performance improved. At the same time, the geographic context of the harbour makes a joint terminal complicated to achieve. As vehicle access is needed for both northern and southern piers, a vehicular bridge is proposed a over the Admiralty basin to serve the present Terminal A. However, this solution risks becoming a traffic bottleneck and it would also cut off the Admiralty basin from the sea. It is also unfortunate that extensive parking lots have been envisioned in front of the terminal entrances. Instead, landscaped pedestrian squares would have been preferable.

The team has proposed an important public building with cantilever above the water on the eastern side of the Admiralty basin, creating a focal point in the middle of the harbour. Together with dense housing in northern side of the basin, the Admiralty area would become an active waterfront square.

The project also proposes two large parks – one extending north of the Admiralty basin and the other ensuing from the Methodist church near Kadriorg towards the harbour. Regrettably, the parks have not been well integrated into the street network. Both parks are surrounded with development on both sides. Given the waterfront location, introducing parks that face the coast and the water on one side would be preferred.

Near Kadriorg, at the site of the present beach, the team has proposed new row-housing on reclaimed land. With residential entrances opening directly to the street, the solution raises questions about why a prominent waterfront site should accommodate semi-private streets. Moreover, it remains unclear why the Port of Tallinn even encouraged land reclamation near Kadriorg all together? Urbanistically, there is no need for such reclamation, especially given that there is plenty of land for development in the harbour for decades.

All finalists failed to consider the unique opportunity to balance Tallinn’s spatial inequality and to establish affordable or social housing on publicly owned land in the harbour. Having so far served as de facto affordable residential areas, Soviet era panel districts Lasnamäe, Mustamäe and Õismäe will no longer satisfy the needs of the younger generation. Tallinn needs new affordable housing and the harbour district in the city centre would be ideally suited for 20-30% affordable housing.

Although this was essentially an urban design competition, there were unfortunately no urbanists or planners in the jury. Declaring ZHA’s proposal as the winner illustrates that decisions were made on grounds other than improving the urban integration of the port and the city centre. The lack of public coordination of parallel initiatives during the competition also produced confusing. During the competition, the city government approved the detail plan of the plots adjacent to the City Hall, which the competition brief also asked participants to work on. Almost simultaneously with the competition, the same area (together with a wider waterfront district) was the subject of a Tallinn city centre seafront strategy competition, organised by the city government and the Centre for Architecture. The winner of that competition was announced a few weeks prior to the end of the Harbour competition. Such parallel engagements and uncoordinated activities reflect institutional failure. In urban design competitions, a transparent and well-coordinated process must be ensured. After all, at stake are not only the private interests of a single developer, but the interests of Tallinn as a whole.

ANDRES SEVTSUK is an Assistant Professor of Urban Planning and the head of City Form Lab at Harvard University. He also participated in the second stage of the competition with City Form Office and KCAP Architects and Planners.

HEADER photo by Land Board of the Republic of Estonia.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 winter edition (No 92).

1 For further information on the background of the area and the seafront vision of Tallinn city centre, see Maja 3-2017.