In the search for architectural strategies in times of a worsening climate crisis and diminishing resources, vernacular architecture has moved into spotlight. This is mostly due to its ability to passively respond to the local climate and make use of the ‘as found’—not only in terms of natural resources and building materials, but also in terms of available craftsmanship and local communities’ skillsets. Valuable knowledge of vernacular architecture, a pragmatic yet poetic, and in fact a scalable concept, is mostly passed on through buildings themselves as epistemic artefacts.

The experimental nature of vernacular building and its evolution over centuries reveals a method of trial, error and self-correction. In the absence of architects, it developed by simply doing, trying things out, and observing the results over a longer period of time. With every tree felled and transported by hand, every board sawn and every stone carried by a person, one of the inevitable aims was to use as little material as possible by keeping the construction simple and re-using available building materials. The easier to repair and the more flexible the building, the better. This resulted in architectural resilience based on centuries-long experience.

Various landscapes of the Baltic Sea region were sources of particular palettes of materials; the climate required a specific response that led, for example, to the predominant farmstead typologies. Looking at vernacular architecture around the Baltic, one can observe typological similarities on opposite coasts owing to similar environmental conditions. The availability of certain materials and their specific properties meant that people arrived at similar ways of using them, despite having never talked to each other. But do we really know that? The Baltic Sea, being fairly easy to cross, was a very dynamic place over the centuries. Alongside the activities of the Hanseatic League, there was a lot of informal trade too. Moreover, there were movements of whole cultures that migrated due to wars and shifting borders, taking their building traditions and housing typologies with them. An example of this is the German Hall House, which first arrived from the Netherlands.

One of the strongest qualities of vernacular architecture from around the Baltic Sea is its ability to respond and adapt to a seasonal climate, individual needs, economic and environmental conditions. It can accommodate the individual within the framework of the typical, whilst still being recognisable as a coherent building culture. Today, as we are faced with an increasingly complex set of challenges in architecture, the solution might once more lie in simple doing—in continuing the evolutionary development of vernacular architecture steered by experimentation as an epistemic strategy. Treating architecture as 1:1 built experiments for knowledge production, this strategy bears the opportunity of transferring knowledge through shared observations and conclusions across different disciplines and fields—from research and teaching to architectural practice and craftsmanship.

A research project

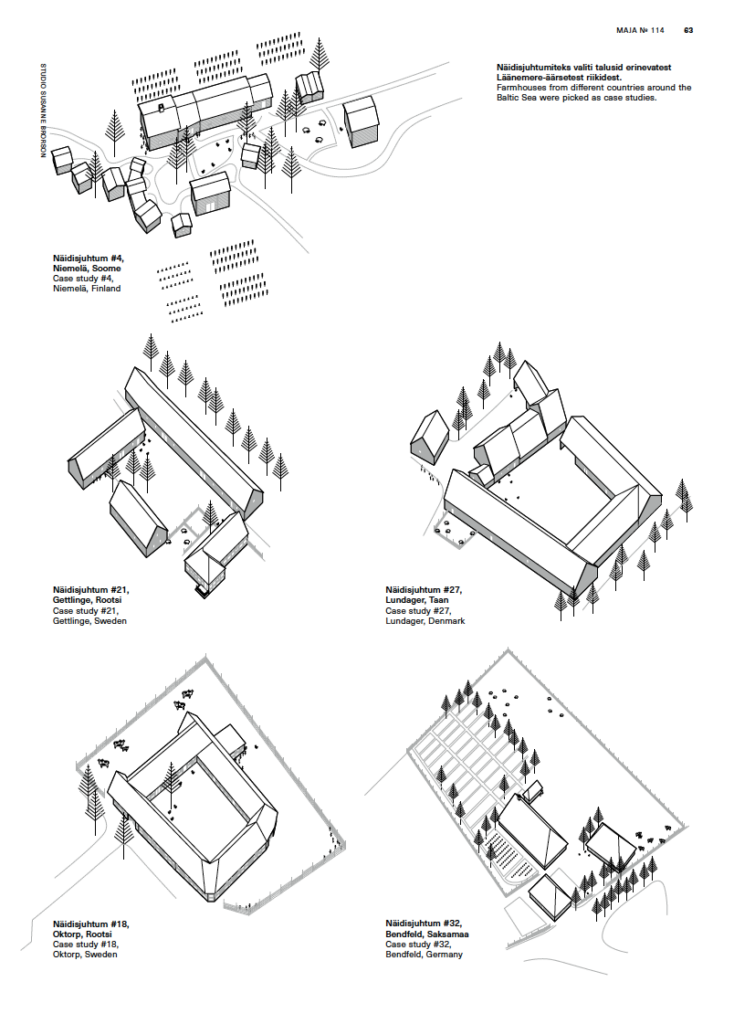

Initiated in 2016 at the Technical University of Berlin, the project ‘Baltic Vernacular—a typological research on vernacular building in the Baltic Sea area’ aims to extract climate-responsive design principles from predominant vernacular farmstead typologies around the Baltic. The research also focuses on the close connection of the farmsteads’ construction and materiality with their location. A lot of wonderful travels through the Baltic landscapes over the past ten years have led to the identification of 32 case studies of rural vernacular buildings that were examined against set criteria. For example, CFD wind simulation was carried out for different times of the year, together with sun path diagrams and the assessment of further climatic data concerning temperature, precipitation and humidity, and a systematic assessment of construction techniques and materials. With a focus on climate adaptation and resource-consciousness, the aim was to establish a set of design principles that could steer the architectural design process towards more sustainability. Local passive strategies emerged as a key in this concept.

In the course of the research project, Baltic islands started to emerge as a valuable source of local vernacular design principles. Their geographical isolation, underlined by limited resources, has resulted in very specific examples of locally adapted vernacular typologies. It is widely known that certain cultural traditions have been preserved longer on the Baltic islands than on the mainland, for example those concerning local language and craftsmanship. The small Danish island of Læsø in the very north of Kattegat region is known for its seaweed roofs. As reed or straw were not widely available on the island, vernacular tradition turned to eelgrass as building material. The impressive seaweed roofs can weigh up to 120 tons and present an exceptionally durable form of construction. They are usually thatched with the help of the local community. Grouped in small villages and embedded in Læsø’s landscape of coastal meadows, fields and shrubland, they appear like a herd of grazing animals.

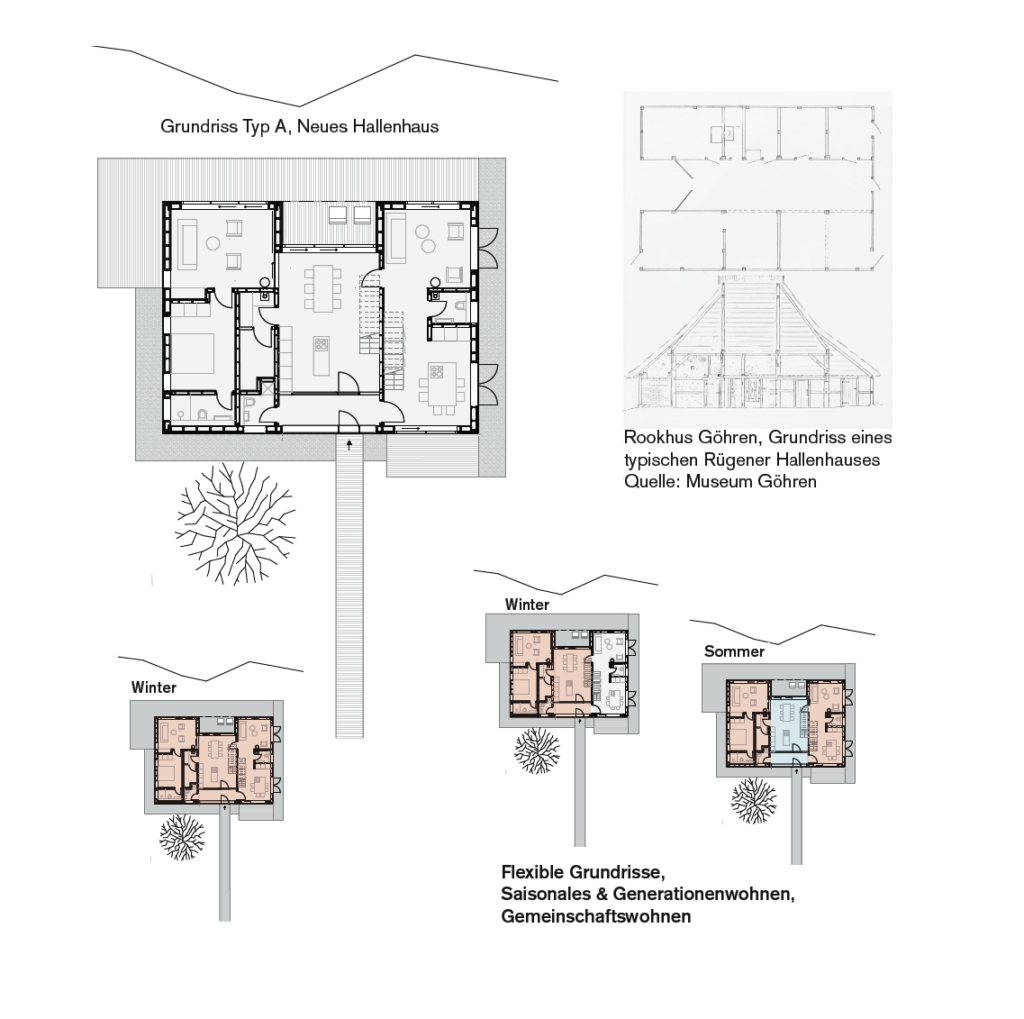

The wind-struck island of Rügen in the Southern Baltic is known for its aerodynamic thatched-roof houses, also called ‘sugar cones’. They belong to the German Hall House typology, although they are very compact and much smaller, and on an almost square-shaped footprint. It is thought that this smaller version developed because of the relative poverty of the inhabitants, or that here the Hall House typology did not develop further for centuries because of the island’s isolation. However, a similar version of the Hall House could be found on the very windy coasts of North Holland too.

The small island of Fårö, far out on the Baltic Sea next to Gotland, has kept alive the tradition of sedge-roofing (and also a very unique ancient dialect that is still spoken there). Every year, the local community heads out to the local coastal meadows to harvest sedges together. In an annual event called ‘tackäting’, which takes place every August, one roof is thatched collectively in the course of one day. The technique of seaweed twisting on Læsø and sedge-thatching on Fårö are somewhat similar.

The Experimental House

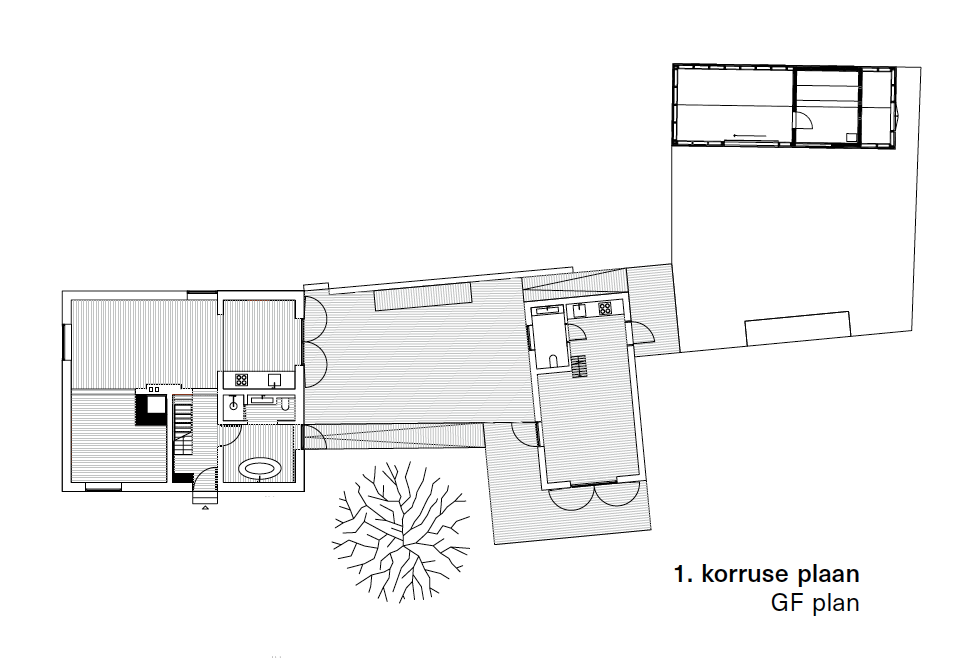

The Experimental House on the Baltic island of Rügen is an ongoing research-by-practice project of Studio Susanne Brorson. The original buildings, ‘found’ in 2005, include a single-family house and a smaller building in the rear. Built in the early 1950s, they had not been lived in for a while, and were in a rather bad shape, with the thatched roof having collapsed. One room on the ground floor had been used for keeping chicken, and as of 2006, there was no bathroom. The main building is of the EW52 type—a serial building type developed in former East Germany to tackle the post-war housing crisis. These pitched-roof single family houses are a typical sight on the territory of the former GDR. They were built in large numbers all the way from the Baltic coast to the mountains in the South—quite the opposite of contextual, or even vernacular. The previous homeowners had made a pragmatic decision to thatch the roof with reed available at no cost in the lagoon close by. Circumstantial conditions of resource shortages in former East Germany therefore resulted in the use of a vernacular building technique.

Over the past 15 years, this small Rügen farmstead has developed into an Experimental House—a testing ground for design experiments related to the adaptation of passive climate-responsive design strategies extracted from vernacular architecture through research. Student workshops, lectures and other events are regularly taking place there and the Experimental House is itself a subject of ongoing design research.

The main refurbishment of the two buildings started in 2009 with re-contextualising the serial design and climate-adapting it. The most prominent change was the erection of a long wall on the north side with an elevated terrace connecting the two buildings. This creates a wind-protected sun space and a microclimate that is usually a few degrees warmer than the surrounding garden. A peach tree is happily growing here together with a Bornholm fig. The terrace is connected to the open-plan kitchen on the ground floor through large terrace doors, letting the warm air flow into the house during warm seasons.

Located in the back garden, the Black-and-White House is an extension of the Experimental House. It utilises the albedo effect. Clad in polycarbonate, the white part contains an unheated space. It has large sliding doors that can be fully opened towards the garden, thus turning this so-called summer living room into a covered external space. The black insulated part, which is black also on the inside, contains a sauna with a large south-facing window. When the sauna is not in use, the space stays pleasantly warm due to solar radiation heating up the black tiles and timber cladding. The space can be used as an additional guest room.

The latest addition to the Experimental House is the Seaweed Monster Summer Kitchen built in 2023. The students of HafenCity University in Hamburg were given the task to design a kitchen that would elaborate on the concept of seasonal outdoor living around the Baltic. The task of creating a kitchen played with a particular material property of seaweed—it is nonflammable. The project was also intended to explore the aesthetic qualities of seaweed as a natural building material. During a design-and-build workshop in May 2023 with students from Hamburg and Aarhus, we erected the building and thatched it with seaweed gathered from the beaches of Rügen. Henning Johansen, a seaweed thatcher from Læsø, supervised the construction.

Seassonal wall dressing

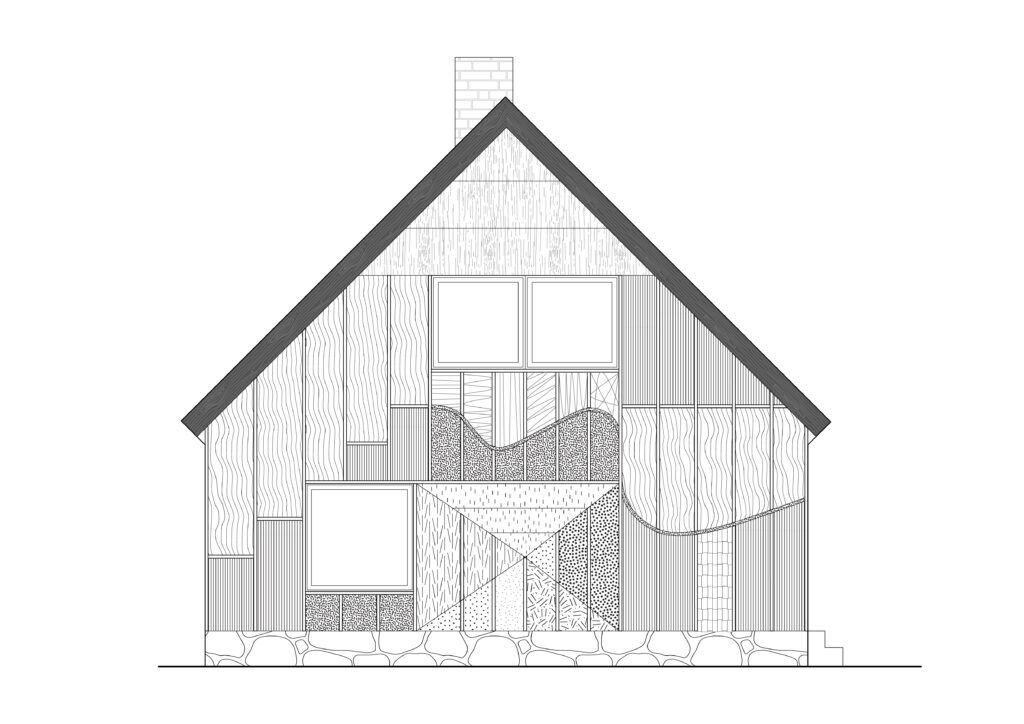

Starting in 2021 with a 1:1 mock-up, the Baltic vernacular method of seasonal dressing—i.e., wrapping up the buildings for colder and windier months in natural materials such as reed or seaweed—was further interpreted and developed into a modular system for the wind-exposed façade of the Experimental House.

At first, several 1×1 metre frames made from larch battens were clad in natural and locally harvested materials, such as reed, seaweed or bracken, and then applied to the wind-exposed parts of the façade. One year later, the experiment was extended to a larger surface. The technique was further explored and experimented with by students from RISEBA University in Riga during a design-and-build workshop. In the course of the workshop, the entire wind-exposed western façade of the Experimental House was turned into a big loom by fitting it with a framework of larch battens with hemp strings running in between. The loom was then woven into by the students, who experimented with several weaving and binding techniques that they had observed in vernacular architecture, but also in textile art.

The seasonal wall dressing experiment continued in August 2023 as a design-and-build workshop with students from HafenCity University in Hamburg. Under the title ‘Harvest to Care’, the workshop highlighted the need to take care of buildings. The application of natural materials was further experimented with by returning to the modular concept of prefabricated natural material layers that could be fitted into the wooden framework of the big loom. The insulating effects of the seasonal wall dressing were felt by the inhabitants of the house, and the façade has become home to a number of insects and birds.

Eco Village Rügen

Eco Village Rügen is a research-by-practice project that comprises nine new residential buildings constructed from prefabricated timber frames. The buildings form three-sided wind-protected courtyards for communal rural living. They are an extension to an existing village on Rügen, located on a windswept peninsula in a lagoon in the centre of the island.

The modular design is based on three building typologies and a binding design guide, which prescribes a palette of natural materials as well as climate-responsive details, such as roofs without overhangs, outward-opening windows and carbonised or untreated larch facades. Walls and floors are likewise kept as simple as possible, with polished screed floors, exposed installation runs and wood-fibre insulation, avoiding foils and sealants as much as possible. Each courtyard shares a ground source heat pump, solar panels and rainwater cisterns. There are also workshops and a shared garden as well as a mobility scheme of e-car-sharing. Fences, cars or any additional outbuildings are not allowed so that nature could regrow into the site.

One specific feature of Eco Village Rügen consists in seasonal floor plans leaning on vernacular tradition. Building type A, the main house, is a larger unit for permanent living, separated by a large central hall from a smaller residential unit that could house the elderly, a rental holiday flat or even a small business. The central hall is fully glazed and acts as a sun space to harvest solar energy. In summer, it can be opened up and turned into a covered external space.

SUSANNE BRORSON is the founder of Studio Susanne Brorson on the Baltic Island of Rügen, Germany. Her work is focused on the topic of climate-responsive architecture in the Baltic Sea region.

Article is published in autumn 2023 edition ISLANDS (114)

Header photo: Studio Susanne Brorson.