‘How do I get to town from here?’

And he said, ‘Well, just take a right where they’re going to build that new shopping mall, go straight past where they’re going to put in the freeway, take a left at what’s going to be the new sports center, and keep going until you hit the place where they’re thinking of building that drive-in bank.

You can’t miss it.’1

Any kind of construction must be stopped.

The construction of the dystopian US motorcity in Anderson’s song must be stopped.

The construction of Tallinn cursed by the Old Man of Lake Ülemiste must be stopped.

The construction of anything new must be stopped.

The construction of the green city must be stopped.

The demolition of the old that is considered construction by law must be stopped.

The current spatial practise in any form must be stopped.

A summary of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report2 was published in March giving the final warning to keep the average global temperature rise at 1.5°C. The sentiment voiced during the corona period to re-evaluate social conventions and work is still a current issue also in the construction sector. According to the report, the current mainstream practise requires radical changes, including the reorganisation of work and production. As said by IPCC, the change must be drastic and climate action must be taken on all fronts: everything, everywhere, all at once.3

The CO2 released by the building industry, not to mention other pollution and landscape scars from mining for materials constitute 40% of the total amount of annual CO2 emissions.4 We do not have time to wait for miraculous technology allowing us to increase production while decreasing CO2 emissions, instead production and our needs need a complete overhaul and reduction.

Update of the present

In the construction sector as well as in politics and mainstream media, we keep hearing the mantra of a future where technology functions more efficiently, people deliver more, the production to create the new and recycle the old keeps increasing and there is no need to give up the acquired comforts. Scientists will invent a Very Modern Machine5 solving all our material, energy, social and cultural problems. In his opening speech made at the literary festival Prima Vista in 2018, Hasso Krull named this attitude an update of the present.6 The mainstream mantra of the future is like a spell enchanting both architects, developers and contractors who believe or hope that the current building culture and pace, which with some minor exceptions have been increasing in Estonia in the past 70 years, can continue in the same manner as technologies improve, energy sources become cleaner and the energy need of new-builds decrease. Is it really so? Is there a limit to construction? Aren’t the new technologies merely creating an illusory cover to the growth that in an environment of limited raw materials is not actually sustainable? How to overcome the belief that new is better and when will we understand that we already have enough?

The state of affairs

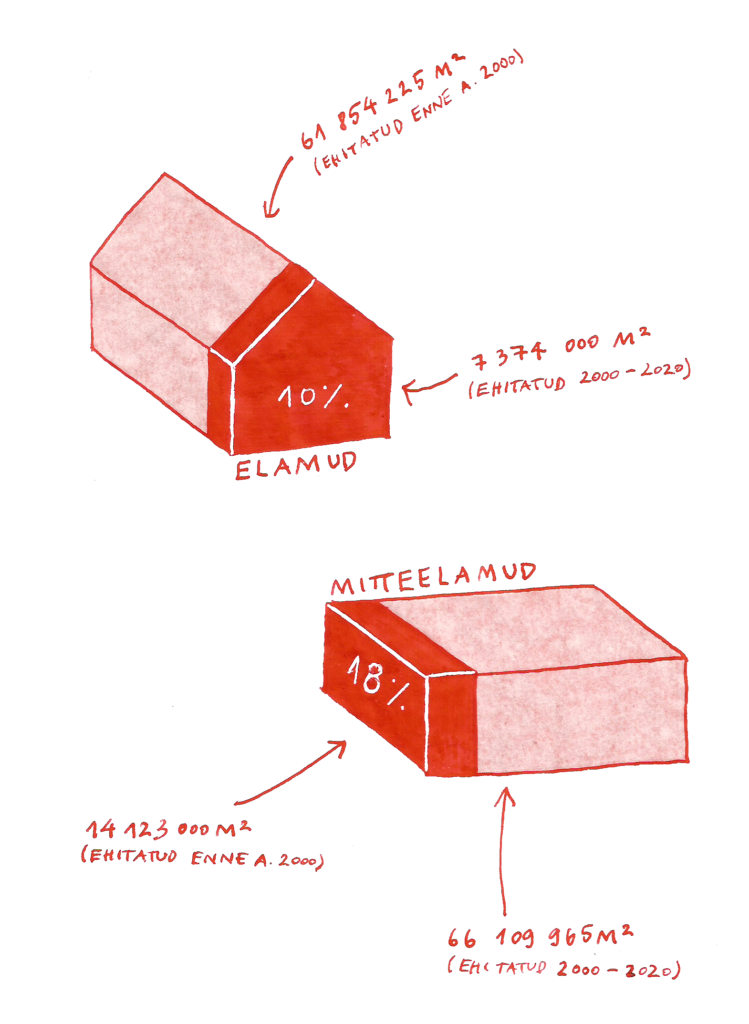

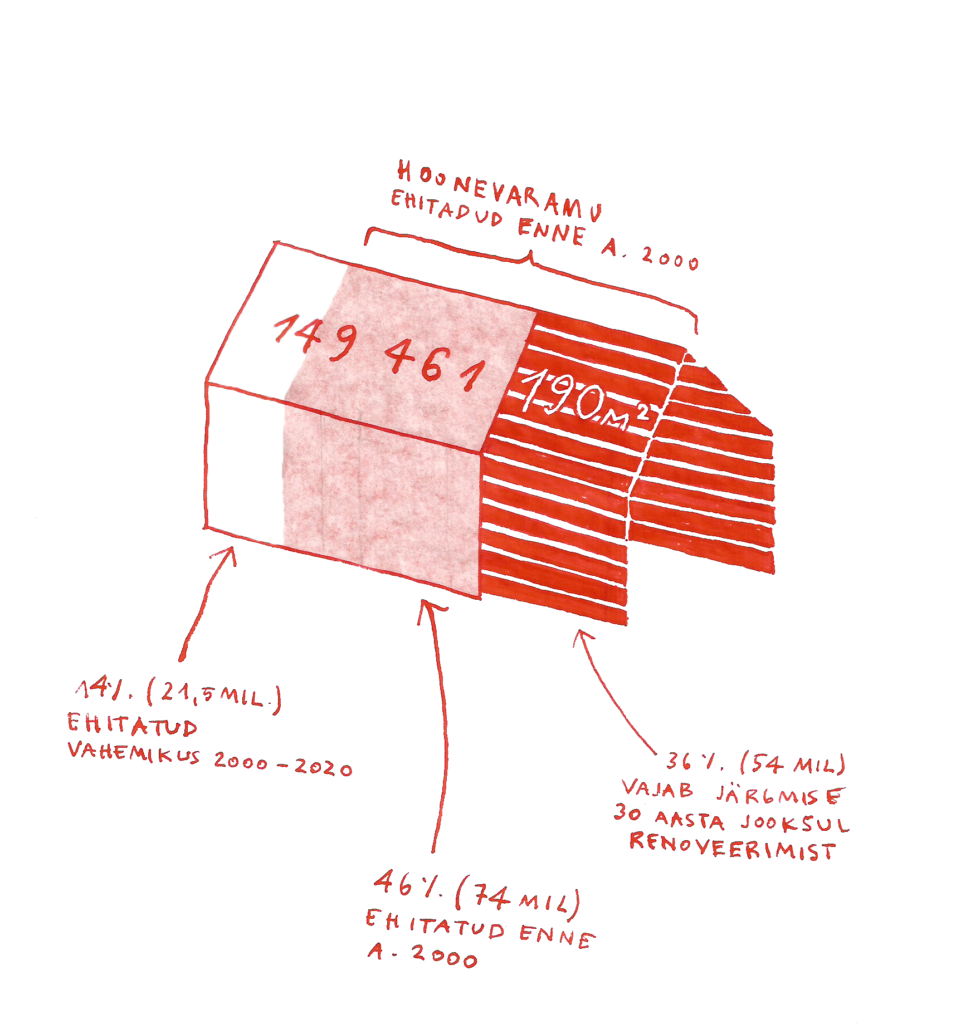

Most of the Estonian building stock in both rural and urban areas is built during the Soviet regime. With the restoration of independence, the boom continued with the building stock increasing noticeably: newbuilds, utility constructions, infrastructure projects and parks with reconstructions and demolitions, renovations and restorations. At the time, also the number of square meters of living space per person increased considerably. In 2001, it was around 24 m2 per person while in 2011 it was about 30 m2. According to Ene-Margit Tiit, the average size of living space per Estonian citizen has remained the same in the past ten years, similarly the number of square metres per person.7 How much personal space does a citizen of a small country with a diminishing population need? The statistics says we have enough space and thus there is no need for new developments.

Valuing and preserving the old is always more sustainable than building something new. According to the study ‘The Long-term Strategy of Building Reconstruction’ published in 2020, 36% of the current building stock in Estonia needs to be renovated in the next 30 years. The study included buildings constructed before the year 2000, with energy efficiency and the quality of indoor climate as the main criteria. Around 100,000 detached houses, 14,000 apartment buildings and 27,000 non-residential buildings need reconstruction.8 Preserving a third of the building stock is a challenge, however, as stated by the head of the Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture of TalTech Jarek Kurnitski,9 properly renovated apartment buildings may function well for the next hundred years. There is not enough raw material in Estonia or in the world to just replace the existing building stock.

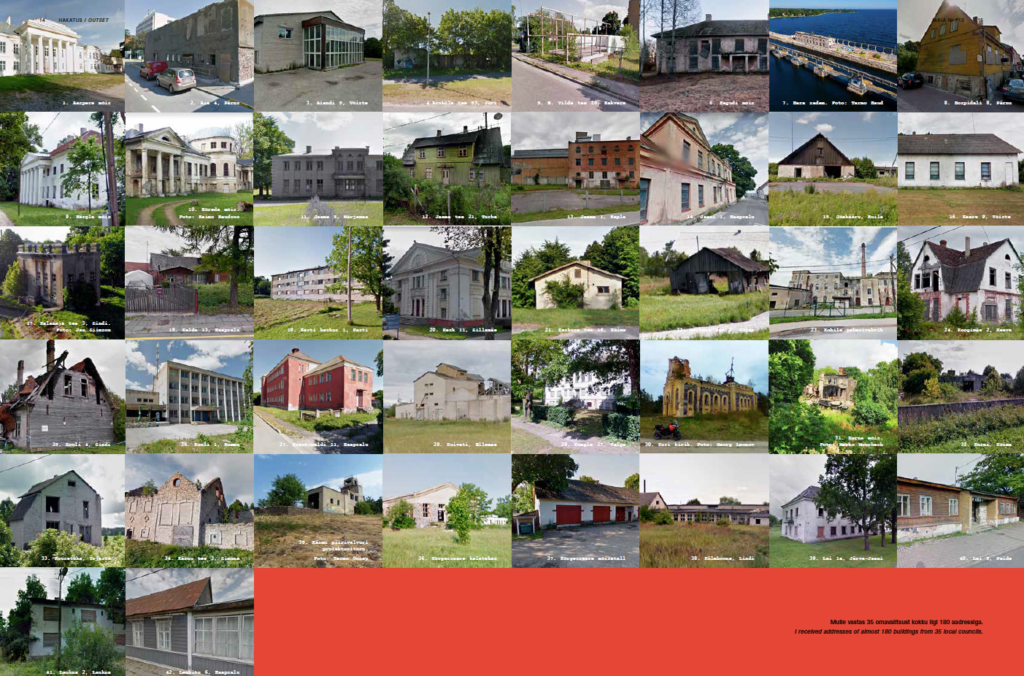

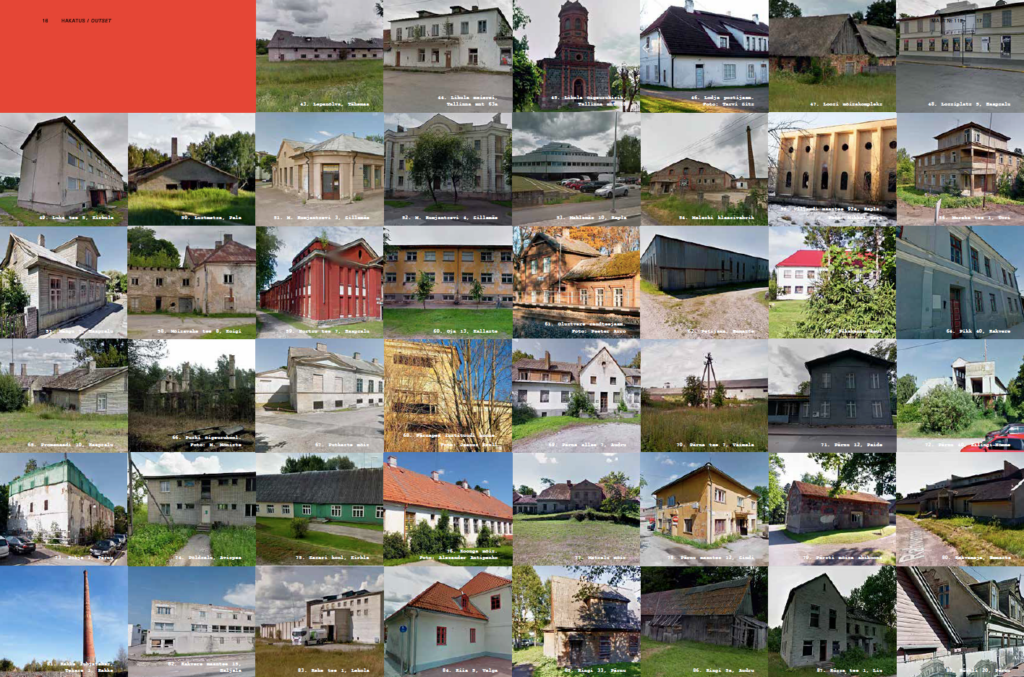

In the shadows of the buildings in need of care, there is another money guzzler—demolition. Outside the fat layer of Tallinn and Tartu, the problem of empty properties is all the more burning. The same study also found that in the next 30 years, we ‘need’ to demolish 2000–4000 buildings at the average cost of 50 €/m2. The reasons for the demolition vary, however, the main aim seems to be tidying up towns and villages. Generally, only hazardous empty buildings, eyesores or half-empty apartment buildings are to be demolished. In some smaller areas, altogether 30% of the buildings could be torn down. It would require an investment around 20 million euros. Who should pay for it? Why is all this money spent? To build a better, more tidy and beautiful environment or another landfill with part of it perhaps used under Tallinn-Tartu Road or Rail Baltic railway dams. The state’s nearly zero-energy building measure has put local governments in a difficult position. In order to get state support for constructing nearly zero-energy buildings, local governments are forced to demolish current buildings with the energy level of D or below to the same extent as taken up by the new-build. This will be the fate of Peri collective farm centre with its recently restored mural ‘Mahtra War’ (1985, Andrus Kasemaa, restored by Randel Saveli).10 The demolition measures urging the construction of more efficient and innovative buildings tend to destroy the current building stock. Why can’t the nearly zero-energy measure support the meaningful renovation of current buildings?

In 2022, a competition was announced to find a contemporary and environmentally economical architectural solution for the new city government building of Haapsalu, with its carbon footprint setting an example for the future renovation projects in the Old Town. A noble effort, if only there weren’t already several empty and neglected historical buildings on the central square that could be adapted for the city government.11 Such projects could be carried out in thriving cooperation with heritage protection specialists combining contemporary architecture and spatial needs with historical urban buildings. A well-considered renovation project that adapts the current spaces to the local government needs and makes the buildings on Lossiplatsi Square and the area between them a unique public facility befitting the seaside resort.

Preserving old buildings is costly, however, replacing, demolishing and rebuilding the current residential and public buildings is even more so. And not only in terms of money, but the costs will be borne by the environment and future generations. The cost of the work left undone today will be carried over to the future and buildings in need of renovation will continue to crumble with their renovation getting increasingly expensive. Then again, costs are all relative: taxing, fining and further complicating demolition will make it easier to decide to preserve, fix and renovate. Preserving the existing building stock will be the main and greatest challenge for the construction sector not only for the next ten years but forever. In construction and architecture—in fact, everywhere—we should apply the philosophy of the 19th-century religious sect called the Shakers who believed that everything built must last with repairs for a thousand years. It’s a philosophy that makes you focus on what you have and how to make better use of it, reveal and expand its hidden possibilities and diversify its uses. We need to create the systems and traditions to enhance this philosophy.

Fasting

The greatest evil: wanting more.

The worst luck: discontent.

Greed’s the curse of life.

To know enough’s enough

is enough to know.12

Is it enough already? In society, economy and culture, catching the moment of sufficiency is a difficult collective effort. The current energy and climate crisis together with inflation have provided a curious opportunity for not doing. Before we as a society decide what to give up (as giving up is a radical act), it’s time to fast. Crises make us think and now we have the chance to fast. To fast from greed and anything new, it’s time to change things and systems, standards and habits, to reconsider attitudes. Just as financial support in agriculture is allocated for the preservation of native forests and meadows, we could value what we have also in architecture by supporting not doing anything both ideologically and financially. In other words, not doing should be just as highly valued as doing has been so far.

Naturally, it is not possible to leave everything undone completely. As mentioned before, a third of the current building stock in Estonia needs to be fixed and renovated. Every year, the number of spaces in need of tinkering keeps increasing. There should be no fears over jobs disappearing in the building sector. The renovation of existing spaces requires a considerably greater effort as every building and reconstruction is a non-standard project requiring custom solutions. The material potential of buildings has been a frequent object of exploration, in particular the reuse or recycling of the demolition and reconstruction debris and the reassembly of the materials into new buildings. These solutions are expensive, but so is any construction. When the new is no longer possible, there is no other way but to use the existing. Architects have a considerable role to play here as they can design buildings relying mainly on recycled materials: logs from the neighbouring house, furnace tiles from granny’s next-door neighbour, windows from Kilingi-Nõmme etc. This, in turn, highlights the need to reconsider the current building standards and methods. Flexibility, mastery of materials and slow pace should replace the so-called high-tech and smart solutions. Differently from a kratt,13 not doing and not building provide architects, engineers and contractors with creative and exciting challenges, allowing them to develop a unique architectural language where spaces become a collective creation displaced in time. The concept of a clean slate in spatial design should be left behind.

The above thoughts stem from my Master’s thesis ‘30 Years of Pause. Research about doing not’ defended in 2021. I still dream that architects and builders should also be gardeners, educators, cultivators and caretakers, cleaners and tinkers, repairmen and flower-waterers. I believe that architecture could be conceived and understood also through non-building with the client commissioning for non-construction. I am still figuring out how not doing can be a valued approach in architecture, both in my personal and professional work.

ULLA ALLA is an architect-artist practicing in Tallinn and Tbilisi. She is one of the founders of VARES architecture residency.

ILLUSTRATIONS by Ulla Alla

PUBLISHED: Maja 112 (spring 2023), with main topic Moratorium

1 Laurie Anderson, „Big Science“, Big Science (New York, Warner Bors, 19.04.1982).

2 IPCC or the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was established in cooperation with the World Meteorological Organisation and the UN Environment Programme with the aim of advising governments on the topic of climate change and assess its impact.

3 Fiona Harvey, „Scientists deliver ‘final warning’ on climate crisis: act now or it’s too late“, The Guardian, 20.03.2022.

4 Ehituse teekaart 2040. Editor-in-Chief Pärtel-Peeter Pere. Rohetiiger (Tallinn, April 2023).

5 The Very Modern Machine is a utopian architectural dream: the authors have invented a machine producing necessary objects and things for people while removing all unnecessary things. The manufacturer sometimes needs to replace the machine with a more recent model. Aleksandr Brodsky, Ilya Utkin, ‘Dwelling House of Winnie-the-Pooh in a Big Modern City’, Projects 1981–1990.

6 The speech is also published in Krull’s collection of essays. Hasso Krull, ‘Imelihtne tulevik. Kaheksa kannaga manifest’, Imelihtne tulevik: manifeste ja mõtisklusi 1995-2009 (Tartu: Vabamõtlejad, 2020).

7 Ene-Margit Tiit. ‘Kuidas on meie elamistingimused viimase saja aasta jooksul muutunud?, The blog of Statistics Estonia.

8 Hoonete rekonstrueerimise pikaajaline strateegia. Compiled by the Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture of TalTech and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communication (Tallinn, July 2020).

9 Reimo Sildvee, „Ekspert: korralikult renoveerides püsivad magalarajoonide hooned veel 100 aastat“, ERR, 20.03.2023.

10 Riin Alatalu, „Nullenergia veab vägisi miinusesse“, Sirp, 18.06.2021.

11 Annika Valkna, „Esindushoone kuurorti riismete vahel“, Sirp, 02.12.2022.

12 Laozi, Dao De Jing. Ursula K. LeGuin translation.

13 A controversial helper creature from Estonian folklore, created from common household objects and given life by the Devil. A kratt was an endless helper to its master, until work runs out, when it would turn against its master and kill him/her. A kratt could be defeated by giving it a meaningless job that cannot be finished like building a ladder out of sand.