An industrial construction technology based on modular and reusable building components can resolve many problems in the construction sector.

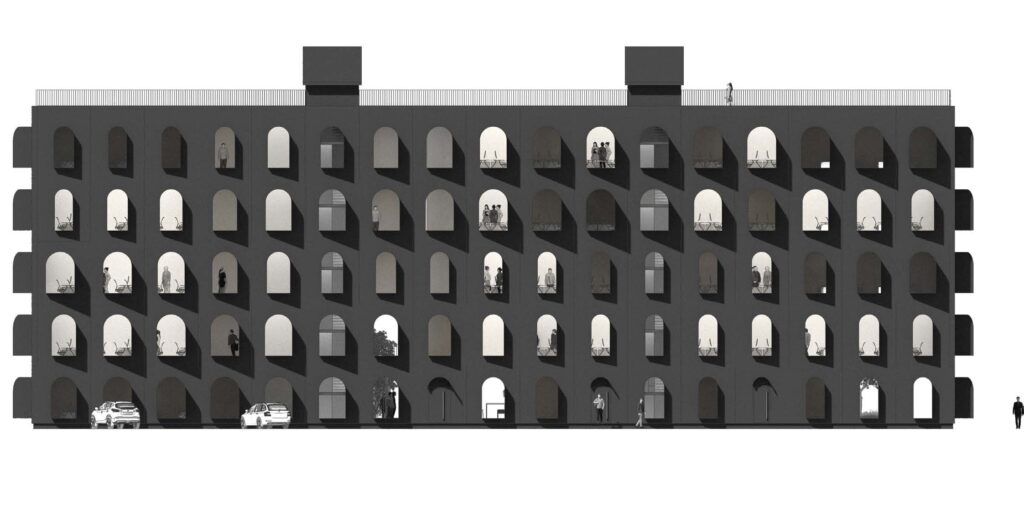

Before proceeding to the article proper, let us entertain a quick thought experiment. What associations do the pair of words ‘pattern’ and ‘building’ evoke in you? Maybe a catalog house pops into your mind? Or do you associate these words with house-patterned textile or maybe with the idea of urban canvas? Apparently, few people associate the term with Tallinn House or a specific type of the Soviet-era large-panel apartment buildings. Indeed, the latter ones could be considered as pattern buildings, as they follow a systematic approach and design pattern.

What is a building pattern?

While construction is often blamed for the lack of systematic approach as compared to automotive and aircraft industries, it is clear that modern houses cannot be designed and built like automobiles or aircraft, i.e., as objects which normally have no relation to the surrounding environment. Kendall1 claims that new buildings should be mass-customisable—i.e., systemic yet adaptable to the regional climate, local building culture, building codes, planning regulations and needs of the client. In short, patterns are technologies for creating such buildings.

According to Christopher Alexander, the author of the perennial A Pattern Language, a pattern is an archetypal and reusable solution for the design of space and objects. A single pattern can generate design solutions from a door handle to large urban infrastructure projects. Alexander’s patterns constitute a ‘language’—a set of principles that is used to design urban space and buildings. His patterns are aesthetical, constructive and political instruments which operate at different levels of spatial design and construction.

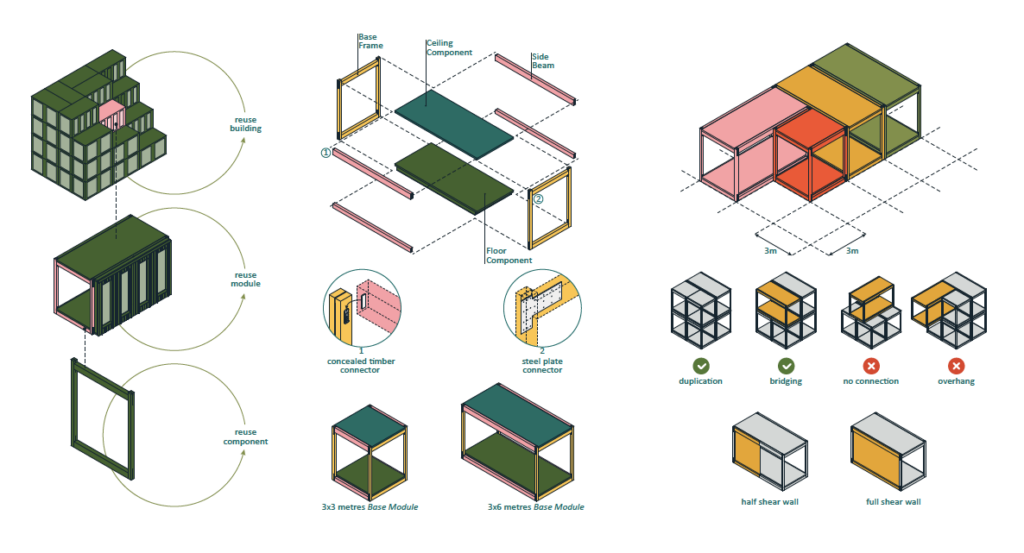

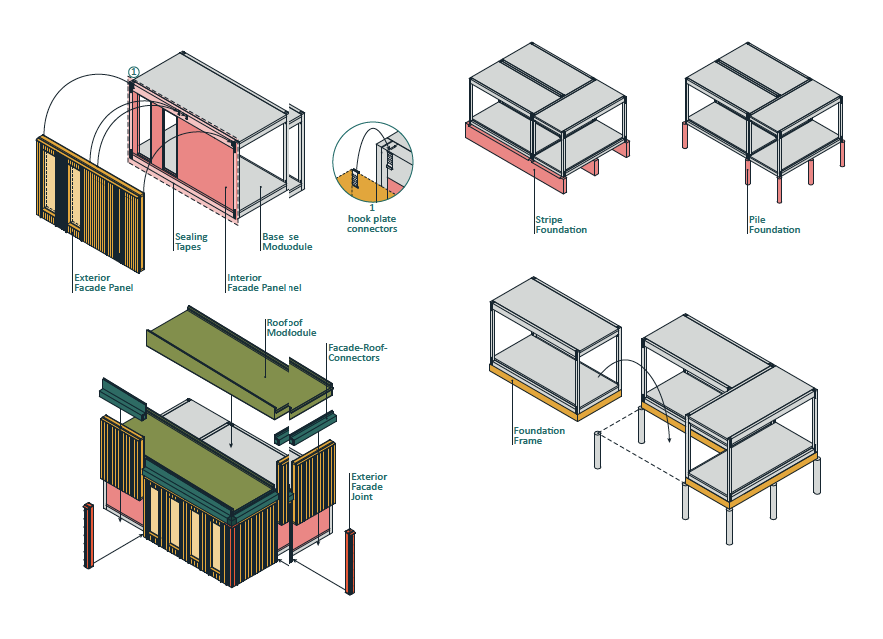

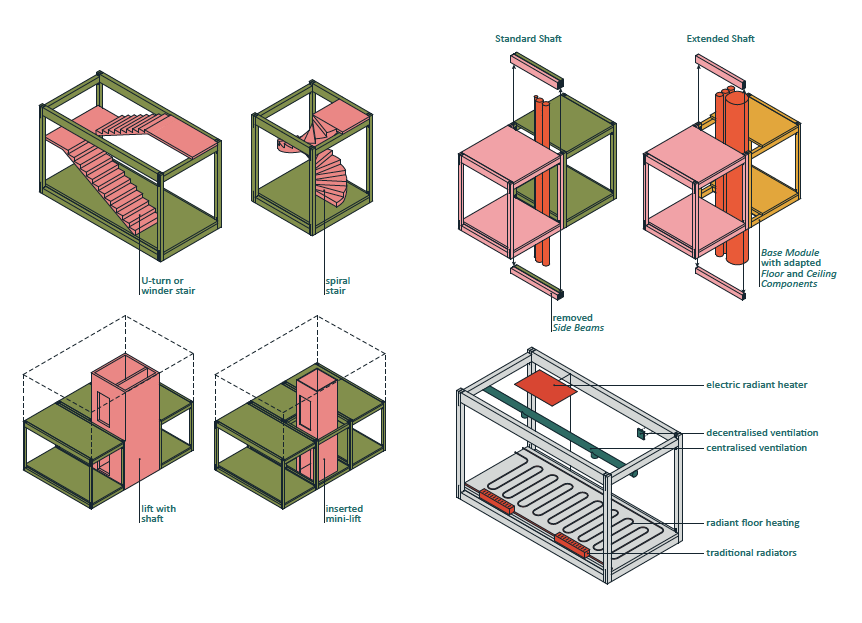

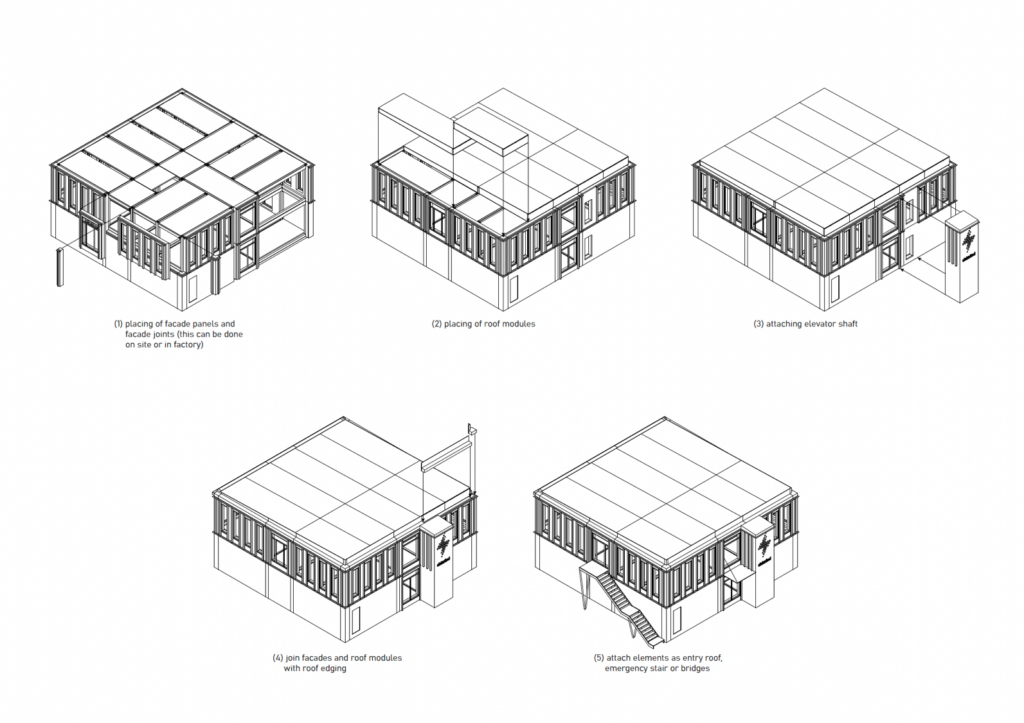

Based on Alexander’s concept of pattern, the building pattern could be construed as a system of components and principles of modular construction, which lends itself to the design and construction of buildings within a size range and of specific typology. In addition to the modular ’building blocks’ themselves, the pattern also includes the principles that are applied to joining and combining those blocks. The schemes which are part of the pattern’s instructions for use explain how the spatial flexibility of the solution, stability of structures, their soundproofing, fire safety, energy performance, comfort of use, etc. are achieved.

The demand for building patterns has arisen due to the increasing popularity of modular construction and the shift from project-based to product-based approach in the building sector, with the goal to boost the productivity and quality of construction.2 McKinsey report3 confirms that factory-based off-site construction can slash the construction time by half and reduce the production cost by up to 20%. However, it is my view that these estimates are actually rather conservative and the reality could have even more positive surprises in store for us. Time will tell!

Patterns are certainly one possible mechanism that provides for a smooth and efficient communication flow between the design and production stages. On the one hand, upon request, the designer can instantly receive from the manufacturer the information regarding possible design configurations with material quantities, embodied carbon footprint and the price estimates. On the other hand, the architect’s project can be submitted to the manufacturer in an easily processable and compact format. This allows the manufacturers to give quick price quotes, shortening the entire process and significantly reducing the client’s risks at the early stage of the project.

Several mass-customisable systems are soon to enter the market as a result of academic development work. One of the most remarkable building patterns (originating from the academia) could be the research project Bauen mit Weitblick (’Building with Foresight’), a concept developed under the guidance of Professor Stefan Winter at the Technical University of Munich and proposing a system combined of open-source standard pieces.

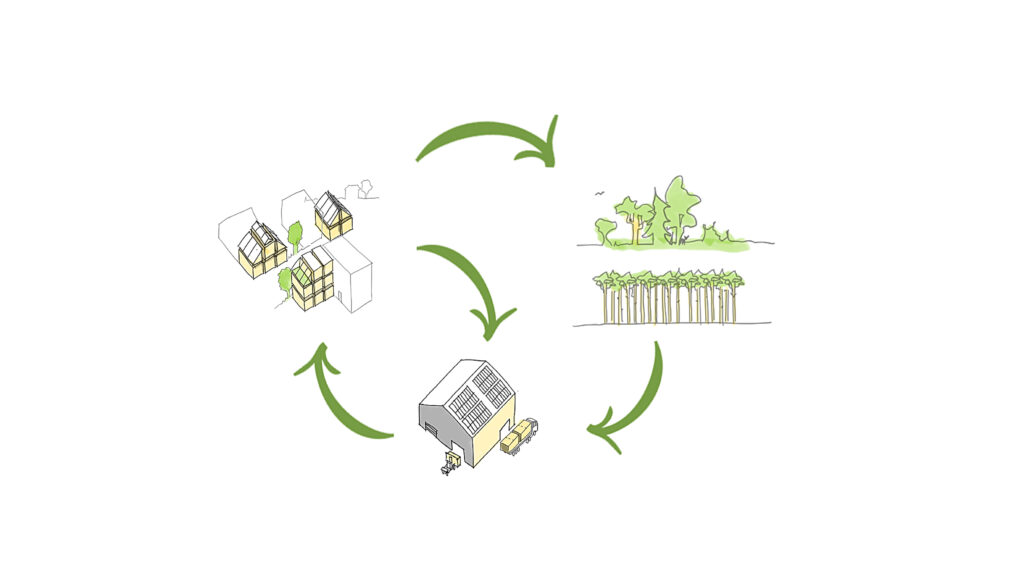

Patterns for reuse and recycle

The assembly, disassembly and reassembly of buildings is already a reality today. The recycle and reuse of the components and modules is part and parcel of the business model of Ramirent, Adapteo, Containex and other companies who offer temporary buildings for lease. If the building is not permanently anchored to a single site, the developer will benefit from a reduced risk of erecting a building with a wrong size at a wrong place. Modular buildings that can be freely assembled and disassembled are essentially a movable property. They need not be a drain on the local authority’s resources, but can be a potential source of income instead, since, when the need arises, they can be disassembled, moved elsewhere or even sold for parts.

Modularity is the key to reuse and recycle in construction. The reuse of full components could potentially be significantly more energy-conserving when compared to the traditional recycling of materials, since no energy is spent on separating and recycling the constituent materials. Naturally, both the assembly and disassembly of components also consume energy, but we can assume it is much less than the energy that would be spent on separating, sorting and recycling the constituent materials.

While construction is often blamed for the lack of systematic approach as compared to automotive and aircraft industries, it is clear that modern houses cannot be designed and built like automobiles or aircraft, i.e., as objects which normally have no relation to the surrounding environment.

Estonian patterns

In recent years, the Timber Architecture Research Centre at the Faculty of Architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts has developed two building patterns—369 and 3cycle. 369 modules are 3, 6 or 9 metres long and (always) 3 metres wide. The structural support of each 369 module is sufficiently strong to hold it together when lifting the module. The building’s skeleton is formed of the modules and of the walls ensuring their rigidity. It is possible to stack up to seven layers of modules upon each other. The system is open-source and its user manual is available on the internet.4

The following principles were observed in the creation of the 369 pattern:

- Informativeness. The technical and structural construction of the pattern building must be clearly visible to the builder, user and maintenance operator alike.

- Universality. The solution must be simple enough, so that it can be manufactured at different facilities and assembled with ease by different builders, and the transportation of its modules can be accomplished without a special permit.

- Energy efficiency. The amount of energy spent in the production, transportation, assembly and exploitation of the 369 pattern building must be reduced to the necessary minimum.

- Reusability. The components of a pattern building must be easily accessible, easily disassembled and reassembled.

- Durability. Considering the growth cycle of the timber used in construction, the wooden parts of the structural components must endure at least 100 years.

- Flexibility. The modular system cannot become an obstructive factor and must be adaptible to the different typologies of different buildings.

- Openness. The concept of a pattern building is to remain available without restrictions for everybody who wants to use it or develop it further, including for commercial purposes.

- Autonomy. The functional units of a building (e.g., apartments) should be independent of each other both in terms of accessibility and separation of utilities.

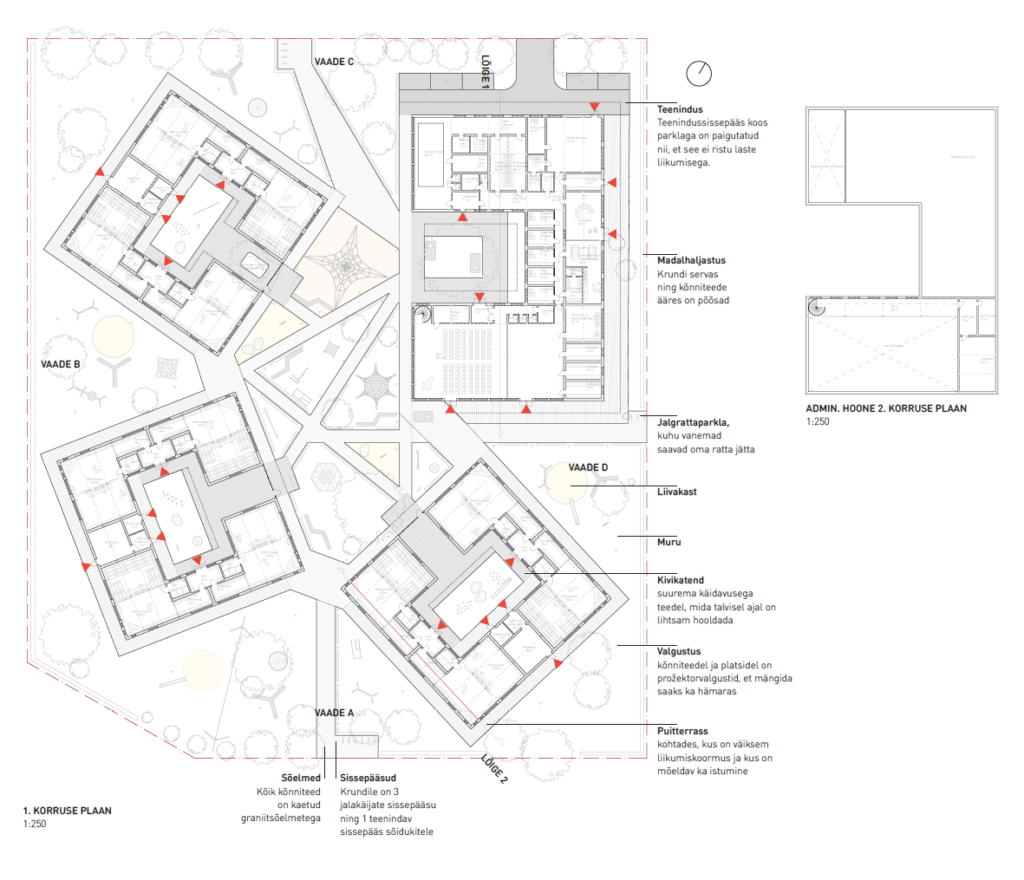

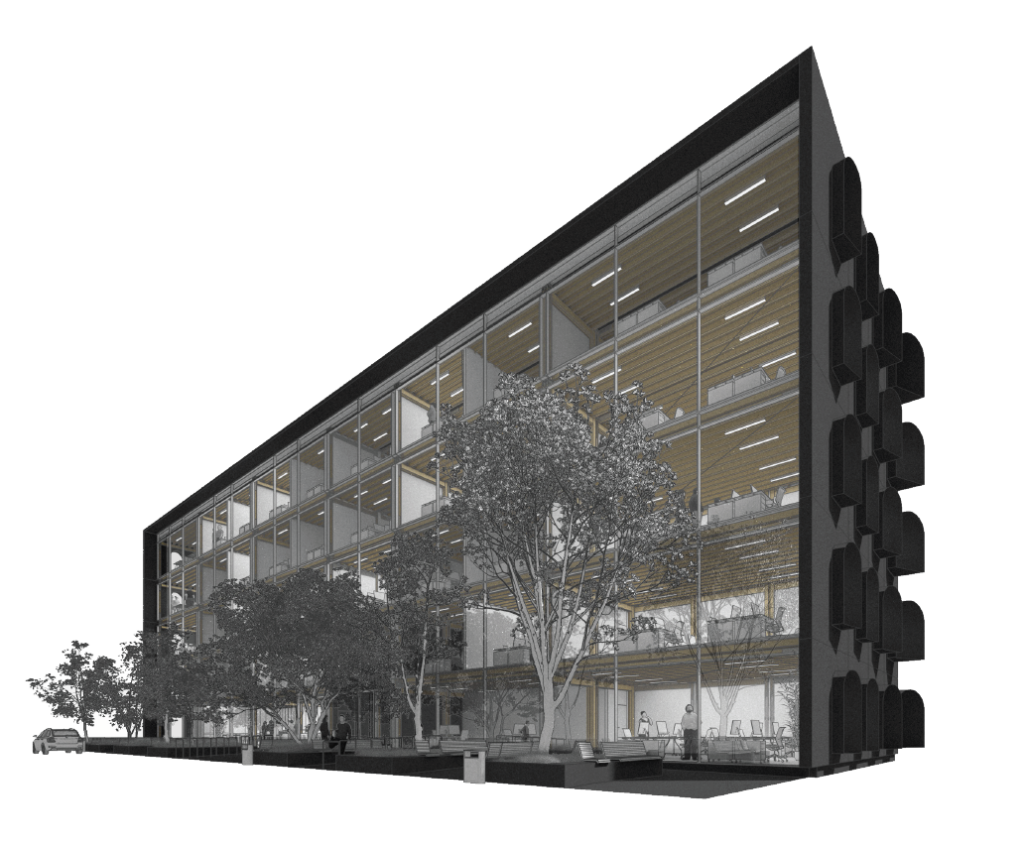

The 369 pattern was used for the kindergarten architecture competition held in the autumn of 2022 in North Tallinn. The goal of the competition was to find a flexible solution that could be adapted to different plots of land and to the construction or renovation of different-sized kindergartens. Based on the diverse works received for the competition, it can be safely said that architects are ready to use the pattern. The winning work created by Inphysica Technology and KUU architects clearly shows that the set frames do not limit the creative approach. As a result, we have obtained an industrially produced model kindergarten design with a significantly smaller environmental footprint, but at the same time very child-oriented.

3cycle is an upgrade of the 369 system and is intended to serve as a basis for the building of educational facilities with 1 to 4 floors. The 3cycle system was used in the design of the Kiili Training Centre of Elektrilevi. As the development of this pattern took place at the time when global supply lines were disrupted and the prices of construction materials soared, local materials were used in 3cycle structures. The standard modules have been optimised with the goal to reduce the amounts of used materials and thereby also the cost of the building’s production and assembly.

The creation of a pattern will be justified if the need for that particular pattern is sufficient enough. Larger modular building manufacturers indeed have developed a set of their own private patterns. Unfortunately, the output capacity of an average Estonian manufacturer is not enough to justify the development of one’s own private patterns. Therefore, patterns should be open and created for shared use.

Public sector to develop public patterns

A pattern serves as the foundation for fast design of buildings and simplifies the tendering process for construction projects. The Elektrilevi project has demonstrated that, after some persuasion, the private sector is ready to meet the demand and start bidding for the construction of pattern buildings. When the contractor, having participated in the first bidding, has learned the pattern, each new time the whole procedure will be significantly simpler and quicker. That is because every subsequent project employs components which have already been created and priced earlier. As a result, conducting value-based tender process for construction projects will become much simpler and more transparent.

The creation of a pattern will be justified if the need for that particular pattern is sufficient enough. Larger modular building manufacturers indeed have developed a set of their own private patterns. Unfortunately, the output capacity of an average Estonian manufacturer is not enough to justify the development of one’s own private patterns. Therefore, patterns should be open and created for shared use. Patterns in which the potential public interest is the greatest could also be made available to everyone as a public good.

The Estonian official long-term strategy for the building sector5 assigns the public sector the role of a leader and role model as a smart client and promoter of innovative solutions. Moreover, by 2027 all new public buildings must be nearly zero-emission buildings. The achievement of this goal could be expedited through the use of building patterns. At the same time, except for the larger cities, the local authorities lack sufficient resources to develop building patterns on their own. It would be logical if this was carried out at state level—by ministries, their relevant departments, state-owned public sector undertakings and public research and development institutions.

The development of patterns is essentially an R&D service which the government can procure from competent institutions. If the specific service involves the creation of a pattern for public use, the contracting authority can forego the complicated public procurement process. The Public Procurement Act (s. 11(1)(19)) specifies that, where the contracting authority is not the sole entity to benefit from the procured R&D service, the public procurement procedure need not be observed. In other words: the development of public patterns can be commissioned without getting entangled in unnecessary bureaucracy.

In summary: building patterns could be among the fastest and most transparent ways to create of high-value environment, the principles must be agreed upon by all links in the value chain from the client to the builder. The key to defining the principles lies in the openness and it is held by the public sector.

RENEE PUUSEPP is an architect, construction technology entrepreneur and Senior Research Fellow at the Faculty of Architecture of the Estonian Academy of Arts.

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest

1 Stephen Kendall, ‘The next wave in housing personalization: Customized residential fit-out’, in Mass-Customization and Personalization in Architecture and Construction, ed. Poorang A. E Piroozfar and Frank T. Piller (Routledge, 2013), pp.42–52

2 Patrik Jensen, Configuration of Modularised Building Systems (Licentiate thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2010)

3 Nick Bertram, Steffen Fuchs, Jan Mischke, Robert Palter, Gernot Strube and Jonathan Woetzel, Modular Construction: From projects to products (McKinsey report, 2019)

4 https://patternbuildings.com/docs/

5 ‘ Long-Term View on Construction 2035’, https://eehitus.ee/timeline-post/long-term-view-on-construction/