The following text is an attempt to conceptualize the architecture of the new Estonian National Museum building as a process. The focus of the article lies not so much on what the museum’s architecture is as on what it does. The individual user’s experience is not in the spotlight, but rather Estonian history. So, let’s ask ourselves, what does the museum’s architecture do with Estonian history?

Jorge Otero-Pailos, an architect and one of the founders of the critical school of heritage studies, recently wrote about what he called experimental preservation: how artists, architects and other activists, with their different creative initiatives present items and phenomena that usually are overlooked by the institutional heritage conservation. The key consideration in the case of objects cast in an experimental preservation role is not its materiality or durability, but rather the conceptual and polemical phrasing of the problem, which incites discussion in society about whether the specific phenomenon is valuable or not. An object cast in the role of experimental preservation can also be ephemeral by nature, transient in time and space.1 Going by the categories of the UNESCO world heritage list, it could be seen as intangible heritage, but it is not always that.

One of the most intriguing examples of experimental heritage mentioned by Otero-Pailos is The Palace of Doubt (Palast des Zweifels, 2005), a work by artist Lars Ramberg, which consisted of temporary illuminated letters installed on the roof of the former DDR’s Parliament building in Berlin, Palast Der Republik (built in 1976). A building that to 21st Germans symbolized the period prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall, was not only darkened by the shadows of the authoritarian Eastern Bloc but also bore a stigma for many in the material sense. Yet after it was abandoned, the house became a popular bastion of culture in the city, a venue for concerts, parties and exhibitions. Ramberg’s work brought the former parliament building into the public consciousness in a slightly altered form at a time when there was active discussion about whether the complex should be demolished or renovated. The artist’s gambit did not pass unequivocal judgment on the value of the building but made the public to think about what was perceived as important in their recent past and what people were ashamed of.

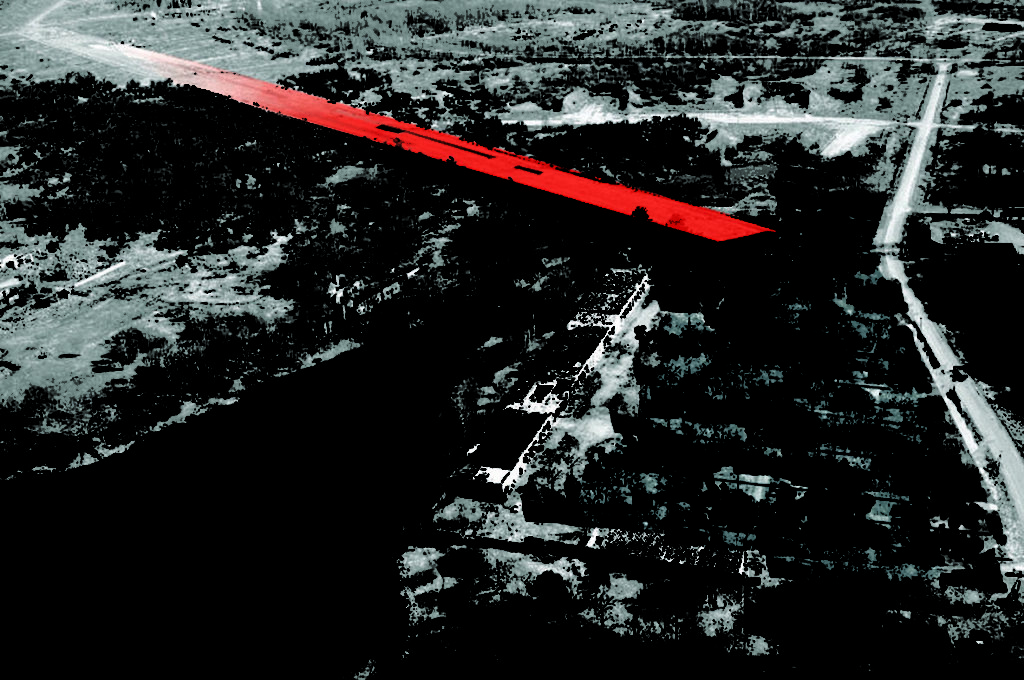

In their winning entry for the competition for the new Estonian National Museum building, Lina Ghotmeh, Tsuyoshi Tane and Dan Dorrell (DGT Architects) made the former military airfield the conceptual centre of their design. For quite a few Estonians, it was a controversial decision; it even met with some outraged opposition.2 It was true that during the Soviet times the airbase was so important that American ICMBs were aimed at Tartu. The history of the Raadi airfield complex is however much longer, going back to tsarist Russia at one end and extending into the era following restoration of independence. There was also a military airfield there during the first Estonian independence period (1918–1940). The history of Raadi reflects the history of the Estonian nationhood and the occupation periods that alternated with independence. For that reason, DGT’s decision to choose a military airfield as the location can be interpreted as the act of holding a mirror up to the Estonian nation and state. Are we ready to stand face to face with everything that has happened in the past?

This type of approach to the problem makes DGT’s museum idea an act of experimental preservation as described by Otero-Pailos. The military airfield with its layers upon layers of controversial history was a concept the architects tossed at the Estonian public – is an airfield worthy of being a location for the museum, can we talk about all that has gone before in history? Taken another way, the decision to move to Raadi airfield can be construed as the desire to take history back, re-write it in a suitable manner, create a new meaning for the place, become its masters again. Estonia has dealt with this kind of deliberate shift of historical memory and meaning prior to the museum, too.

The architecture of the National Museum presents the former military airfield to the public as an historical multilayered object, without pronouncing final judgment or appraisal on it. Maybe the museum’s architecture even opens Estonian history as a whole up to view and debate, feeds situations and historical artefacts to the local public and museum-goers in the manner of a moderator with no personal stake in the matter, who stands on neutral position? If that’s the case, the role of the museum’s architecture as generating this kind of polemic is reminiscent of the problematics of modernism as described by Anthony Vidler. According to Vidler, both the histories of modernist architecture (in the sense of historiography) and individual architectural works should be seen as phenomena that shape and help us to make sense of our own modernity and historical consciousness, expose preconceived notions and clichéd thought patterns.3

Vidler strikes a contrast between modernist and post-modernist conceptions (about architecture). Whereas modernist mindset was exceedingly aware of history and the quality of being historical (of being determined by history), trying to respond to the past actively, mainly through resistance to it, postmodernist thinking makes direct use of history, selecting the passages suitable to its own purposes.4 The postmodernist approach would appear to deny its own direct historical-ness and tries to construct an appropriate reality, illusion for itself, using select historical fragments. Modernism, on the other hand, accepts everything that has gone before, even the negative aspects, and tries to respond to it through its own self, supported by a contemporary sensibility of life, and trying to remain as honest as possible – in short, trying to be modern.

Transposing Vidler’s ideas to the National Museum’s architecture by way of analogy, there should be no doubt that the work of DGT, which now sprawls over the concrete runway at Raadi for more than 350 metres, is modernist in its mindset. The architecture of the new museum building treats context as a challenge and tries to actively relate to everything that has been in that location from tsarist Russia to free Estonia. The architecture thus doesn’t just have a narrowly nationalist ambition; instead the building’s concept is characterized by the architects’ desire to understand the historical context, and in response to it, to create a new layer, an activity space and possibilities for the current moment and the current people. The National Museum architecture thus contains a certain psychoanalytical or therapeutic component, as if signalling that history should be accepted, no matter how brutal and frightening its contents, and continue forward. It must be said that walking in the new museum building, it doesn’t seem that this therapeutic reconciliation function is working perfectly yet.

The Estonian National Museum is an institution whose implicit driving force is to engage with the nation’s history, impart meaning to it, which presumes clear (national) ideological choices. Here we can trace the difference between the National Museum’s modernist architecture (in Vidler’s sense) and the institution’s own core values. The new National Museum building has forced both the National Museum staff and local public to reassess and rethink Estonian history, the scattered, partially debunked narratives, hierarchies and meanings that have existed to this point, and has given a possibility for the emergence of new constructs, and hosting them in the literal sense. The form in which these changes have been materialized is observable in its most direct form in the permanent exhibition on Estonian cultural history “Encounters” (head curator Kristel Rattus). Here the linear and heroic view of Estonia’s national history (for example, the idea of timeline that creates the illusion that Estonian history follows a straight line, as well as “national treasures” such as the display of Estonia’s first tricolour flag), intertwines with a more fragmented micro-history and mini-narrative level that gibes with more recent historiography, focusing on the stories of ordinary people and exhibition of everyday “non-treasure” items.

Can the nationalist ethos, which contains something of an isolationist and conservative dimension, be modernist at all (in Vidler’s sense)? Hard to say. Yet a certain difference between the mindsets can be perceived between the architecture of the new main building and the exhibitions on display, whose designs are modern but which nevertheless construct and reproduce Estonia’s national history. At the same time, it is clear that the museum’s modernist architecture is not submissive to Estonian history and it is not a mere container for showcasing it and presenting the historical truth.

In the new National Museum building, Estonian national history and the building’s architecture exist in a creative but tense relationship. Unlike ritualized, aesthetic exhibition spaces, the runway of rough concrete allows Estonian history to be reflected in a more raw, direct form, revealing the collective traumas and inner conflicts. While exhibitions and the museum’s contents can be seen as a deliberately prepared performance, ceremonial tableau or even mask of Estonian history, the building’s modernist architecture, based on a former military airfield motif, exposes the subconscious of Estonian history and the heterogeneity that has been banished to the subconscious.

CARL-DAG LIGE is an architecture critic and historian, works as a Curator at the Museum of Estonian Architecture.

PHOTOS of Estonian National Museum by Kaido Haagen.

HEADER: The conceptual scheme of the Estonian National Museum competition entry “Memory Field”, 2006, DGT Architects.

PUBLISHED: Maja 89-90 (summer 2017) with main topic Changing

1 Jorge Otero-Pailos, “Experimental Preservation,” Places Journal, September 2016, https://placesjournal.org/article/experimental-preservation/ (as of28.11.2016).

2 See eg Karin Hallas-Murula, “To marry a rapist?”, Eesti Päevaleht 17.01.2006.

3 See Anthony Vidler. Histories of the Immediate Present. Inventing Architectural Modernism. MIT Press, 2008, p 200.

4 See ibid p 193.