SPATIAL DESIGN

In the course of the programme ‘Great Public Spaces’ dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia, the historic street was reconstructed as a contemporary pedestrian-friendly main street. The light monochrome hues of the design create a museum-like exposition complemented with seats, planting, lamps and signage engraved in the pavement and providing information on particular buildings, architectural and landscape objects as well as the town in general.

The field of spatial heritage comes with a kaleidoscopic array of concepts that connect the subject with issues such as the climate crisis, reuse, architecture and urbanism. The used terms need to be clarified and made more familiar.

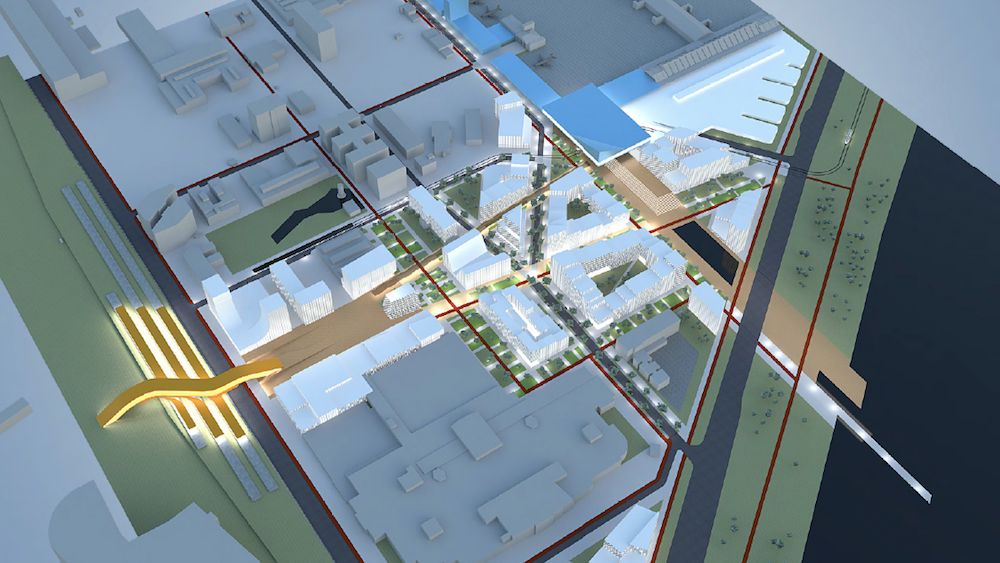

Why is it no longer possible for 21st-century Estonia to continue without a spatial development office, and what kinds of new values would the new office create?

How about we agree that from here on out, we will be implementing only good spatial solutions? Okay?

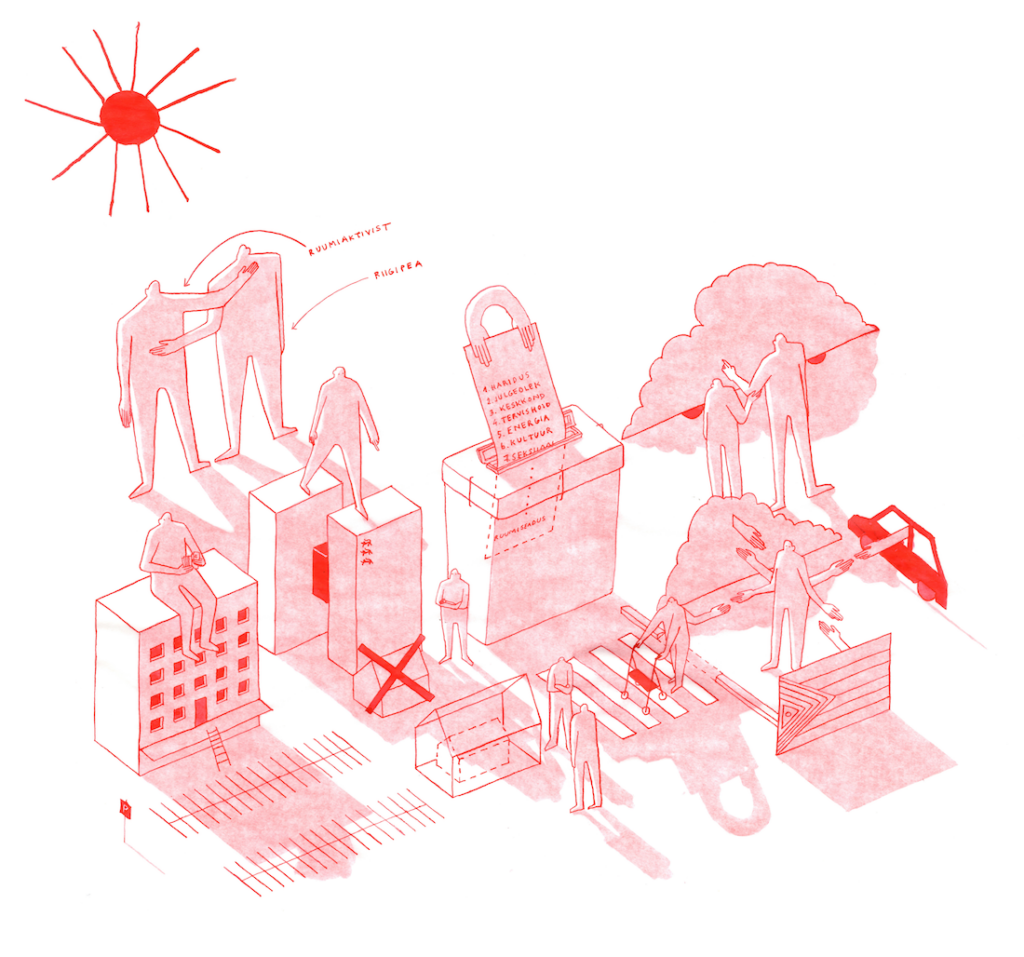

In order to compensate for the bureaucratic inflexibility and sluggishness that is burgeoning in spatial design, a new methodology has evolved that enables to operate in a more democratic, playful, experimental and cost-effective way.

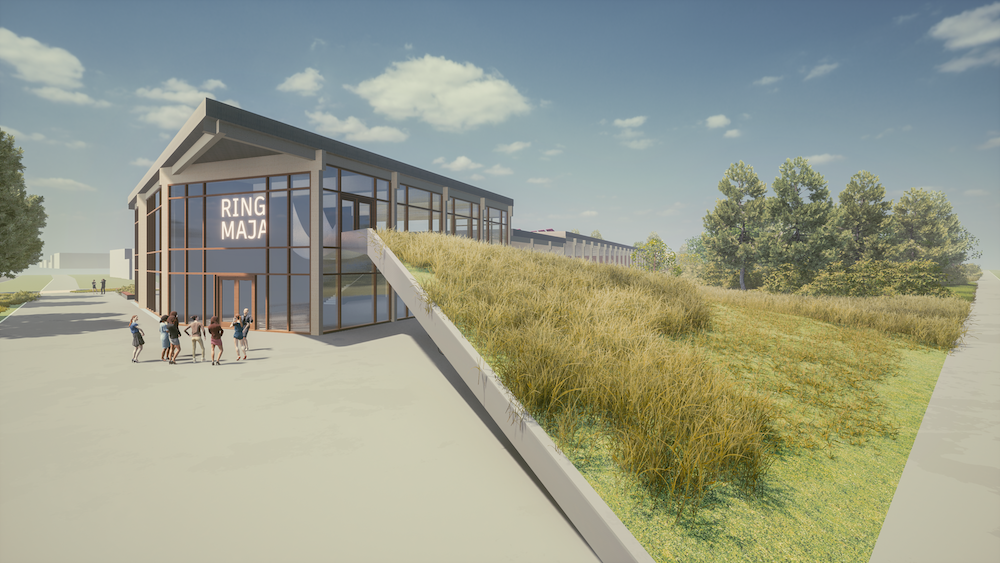

The circular economy centre highlights the potential of waste materials as a reusable resource. It creates possibilities for repairing, reprocessing and using things again.

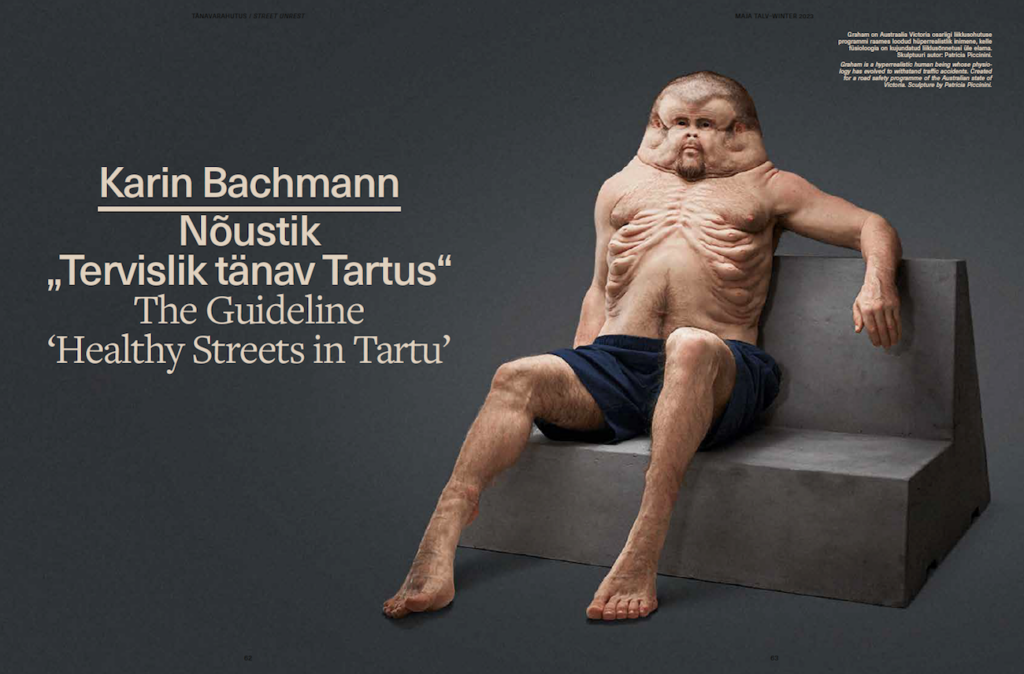

Healthy Streets in Tartu is a guideline providing help for city officials or specialists working on spatial design.

It is no news to architects and real estate developers that the design of a new spatial environment usually begins with parking spaces as if it was the fundamental value. More and more practitioners, however, complain about the outdated mindset related to parking norms and the need for a new approach allowing to implement more sustainable decisions. Tartu city architect and the head of the spatial design department Tõnis Arjus discusses the city’s new ambitious online app considering the parking spaces according to the actual need.

Contradictions of spatial planning are caused by the time required to process comprehensive and detailed plans as well as (spatial) gap between the two. How to better make sense of planning processes and to alleviate rigidity of the aforementioned?

If there is any feeling of blandness, or risk aversion, or scant sense of place, it is not due to insufficient bike lanes or pedestrian squares, but rather because the larger questions of what is produced and who gets to have how much have already been decided.

Postitused otsas