A building with a strong character is easy to hate. Or to love. Take, for example, Tallinn City Hall—few are indifferent to it. Many see the City Hall as an ingenious artificial landscape and urban stage, while others consider it a relict of the Soviet occupation that is unfit for a free Estonia, just like the Sakala Centre that was demolished in 2007. There are many other lesser or better known buildings from the Soviet period that are architecturally ambitious, but unacceptable to many for aesthetic or ideological reasons.

In order to give some distinctive examples, I will introduce a selection of buildings in the city centre of Tallinn that were built in the late Soviet period, after which I will proceed to make some generalisations about the current state of modernist heritage in Estonia, related societal attitudes, and possible future scenarios. Estonian modernist heritage continues to be threatened, because the society as a whole does not value it enough.

Sleeping beauties or slumbering monsters?

The following objects are only a small selection of all the exciting architecture that was built in Tallinn between the 1960s and 1980s—an era that has become known in recent historiography as the late Soviet period. This period is broadly characterised by the modernisation of society, just like in Western countries—active urbanisation, advancement of technology, and the rise of service- and consumption-centred ways of life. The most immediately perceptible changes occurred on various levels of people’s living environment, ranging from product design to an increasingly modernist urban space.

Only a very small part of architecture from the late Soviet period is protected in Estonia—this fact reflects the priorities of heritage conservation in the post-independence period, but also the broader value judgements of the society. None of the buildings introduced below are under heritage protection.

Office building, architects Toomas Rein, Veljo Kaasik, project 1964, built in 1967

Toomas Rein and Veljo Kaasik, who are among the most well-known Estonian architects from the second half of the 20th century, designed a yard-side extension for the main building of the design institute of Estonian Rural Design at Harju 11/Müürivahe 1, in the Old Town of Tallinn. The design was put on paper in 1964, when Kaasik graduated from architecture studies at ERKI. The building was completed in 1967, when Toomas Rein also graduated from ERKI. Hence, this is the building that marks the beginning of their rise to stardom. The main building also happened to be one of the clearest examples of a post-stalinist wave of modernism in Estonian architecture—a straightforward modernist block whose southward-oriented rows of windows illuminated the designing halls and meeting room. The building was insulated rather recently (in 2012), after which it partly lost its original decoration, but for a building with a form so simple, this is not an irrevocable loss. What would be irrevocable, though, would be to demolish the building—and this is precisely what has been decided by the Heritage Protection Board under pressure from a private owner. The building is indeed somewhat out of place in a medieval old town. And yet, it has stood there already for more than half a century by now and has its own fascinating story to tell.

Exhibition pavilion, architects Ants Raid, Ilmo Liive, designed in 1975–1976, built in 1977

The Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy of the Estonian SSR, later known as SOE Estonian Exhibitions, had its first modern large pavilion on Pirita road, in a location that became the main spot in Tallinn for industrial exhibitions and fairs for several decades. The building known as the Blue Pavilion was built by Finnish construction workers with building materials bought from Finland. The architecture of the pavilion is characterised by a technicist aesthetic that results from its industrial materials and modular structures. The building has been preserved in a relatively authentic way and still strikes as fresh, even high-grade, but has lost some of its spatial character due to the architecturally somewhat more boring additional exhibition halls that were later built on both of its sides (A Pavilion a.k.a the White Pavilion 1991–1992; C and D Pavilions 1996-1997).

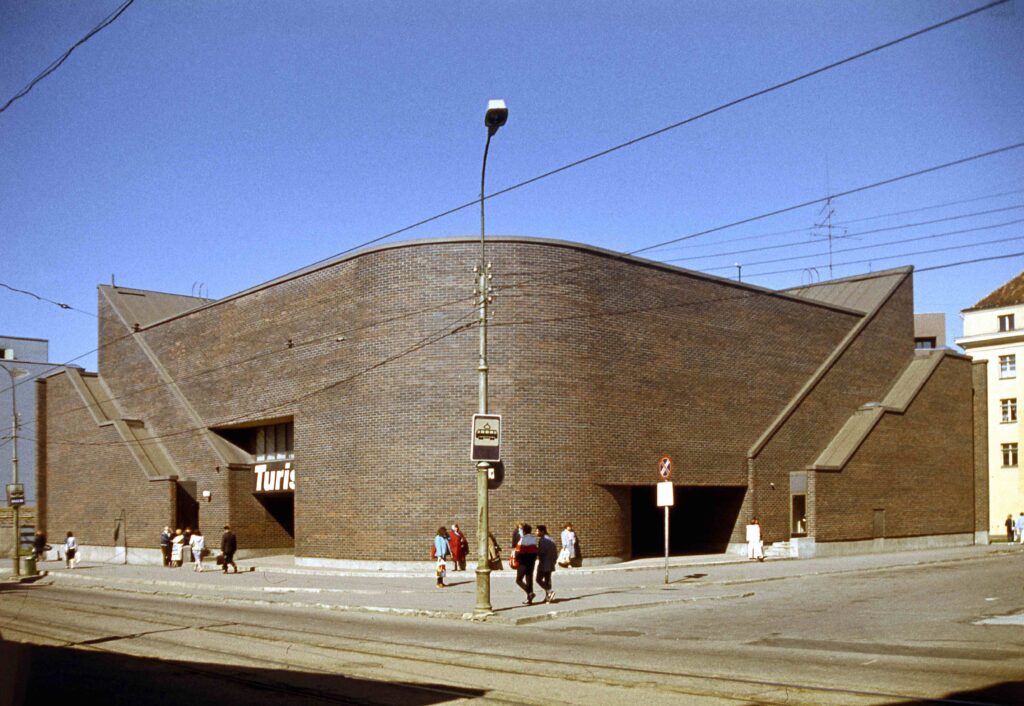

Foreign currency shop Turist, architects Peep Jänes, Henno Sepmann, interior architect Aulo Padar, engineer Enn Kaarelson, designed in 1980–1981, built in 1982

Foreign currency shop Turist is probably the most well-known one of the buildings listed here. It is a unique example of Estonian post-WWII modernist architecture. The building is uncommon in its original function (foreign currency shop), architecture (influenced by the Finnish master Alvar Aalto) as well as interior architecture (one of the most important works of Aulo Padar). Special solutions were also used in construction—the building is made of monolithic reinforced concrete like the others, but the facades were made with clinker brick that was rarely used in Estonia. Given that it was built by a Finnish company and mainly with building materials imported from Finland, the quality of construction is very high. The most important examples of the work of architects Peep Jänes and Henno Sepmann are still intact in volume as well as details of the exterior. For a couple of years now, there have been plans to demolish the building, which would be a great loss for the architectural culture—not only in Estonia, but in all Europe. It is one of the very few Estonian architectural objects that belong to the Docomomo International list of heritage objects. Some years ago, heritage protection institutions tried to take the building under protection, but the owner challenged it in court and won.

Courthouse, architect Paul Madalik, designed in 1978–1984, built in 1990

On Liivalaia street, we find one of the few custom-built and relatively well-preserved office buildings from the end of the Soviet period in Tallinn. The building has simple geometric volumes and a somewhat dull, but serious character appropriate for a courthouse, and it was still used by Harju County Court only a few years ago. As it happened, it became one of the shooting locations in Tallinn for the Hollywood blockbuster Tenet (2020). The relief sculpture that used to stand by the main entrance—Justitia (1991) by Aime Kuulbusch—was transferred permanently to the new courthouse in Tallinn. It would be worth to consider preserving the Liivalaia courthouse and finding a new function for it, but in all likelihood, it will be demolished in the coming years to make room for new development.

The roots of skepticism toward modernism

There are certainly a number of reasons why modernist architecture and modernist urban space are not very popular in the Estonian society. One of the main issues seems to stem from the fact that the spread of modernist space and architecture largely occurred in the Soviet time—for many, modernist space has become associated with the trauma of the occupation period. Although the first, early wave of modernism reached Estonian architecture and urban planning already in the 1930s, its effect was relatively limited. Back then, modern buildings were mostly built by affluent people; before any grand urban plans could be realised, they were interrupted by the onset of the Second World War.

The second reason for skepticism toward modernism—in addition to the political one—might have to do with the substantial changes in people’s way of life in the second half of the 20th century. After the Second World War, urbanisation accelerated, many new jobs were created and new dwellings were built. Granted, a similar process took place in kolkhozes and sovkhozes (collective farms and state farms), but on a much smaller scale. For many, moving from the countryside to the city meant exchanging a quiet, sparsely populated environment for a noisy urban one, where one is surrounded by many strangers and a much denser network of buildings.

Thus, most people in Estonia began to experience modernism first-hand only in the 1960s, when the pompous Stalinist architecture of the early years of Soviet occupation was receding and large new apartment block districts began to be built in order to alleviate the scarcity of living spaces. This was also a time of rapid industrialisation in the field of construction, when craft skills diminished and architecture lost some of its human scale.

It could be that psychologically, Estonians have not even really arrived in the city yet and are still only halfway from the countryside. Many see living in the city simply as an inevitability. It is as if the urban way of life is still being learned—the city has not become a true home yet. This feeling of discomfort might also be one source of skepticism toward urban architecture. The hatred of ‘blocks’ does not originate from a mere difference of aesthetic preferences, but also expresses a certain bitterness toward the urban life.

In sum, modernist space is alien to Estonians politically, socio-psychologically as well as aesthetically. Modernism is not something of one’s own, but rather something that has been hurriedly imposed by someone else. This sort of psychological reluctance is not peculiar to Estonians, but characteristic of also many other societies that underwent rapid modernisation and urbanisation in the 20th century.

A further blow to the reputation of modernist space and architecture was dealt by the poor building culture during the Soviet period. Many buildings of that era have a shoddy construction quality. Even when they are structurally strong, their quality of decoration is very low—either due to a lack of skilled workers or workers’ lack of motivation at the time. Also, many buildings have not been sufficiently maintained over the decades and might look shabby.

Taking these arguments into account, it is not surprising that modernist and especially late Soviet architecture is not much cared for in the Estonian society. Furthermore, we are talking about recent history—these buildings and building ensembles are not yet old enough to inspire people to fight for them. Our society finds it much easier to grasp the value of manor houses or even barn-dwellings than architecture built in the recent past and already with industrial methods.

Whether it be a Soviet-era building or monument—bulldozing it does not remove our troubled history. What it does remove, however, is artistic value, interesting space and an opportunity to make peace (or truce) with history.

How to protect modernist heritage?

I would nevertheless like to underline that houses and architecture are not at fault—not for their contemporary political context, urbanisation nor any technology-driven changes. Interesting, good and original houses and environments have been created at all times, for there have always been spatial designers and architects with original ideas. A particular social order or technology has never stopped exciting buildings from being built.

When it comes to protecting modernist heritage, perhaps we should do more to emphasise the uniqueness and original architecture of individual buildings or environments? Tallinn City Hall might be an offspring of the occupation period, but there is nothing like it anywhere in the world. By demolishing it, we are impoverishing not only the urban space in Tallinn, but also the architectural culture of the whole world. The City Hall is a prominent single object, but the issues related to its protection and preservation are also relevant for the rest of late Soviet architecture in Estonia—above all, we should appreciate the architectural quality, spatial uniqueness and creative potential of a building. The political aspect should be acknowledged and looked boldly in the eye—traumatic history cannot be swept away, but one can make peace with it, offer an interpretation of it that is appropriate for the current moment, and find new functions for the building.

Estonian heritage protection institutions have had various initiatives aimed at post-WWII architectural heritage. Unfortunately, only a handful of buildings from the 1960s–1980s are currently protected. Many exciting buildings of that period have already been demolished or completely redone, because they were not protected as cultural monuments. Smaller baseline studies have been commissioned by local municipalities (e.g., the urban planning department of Tallinn) who have tried to protect particular buildings or groups of buildings through zoning. Alas, this has not led to any major shifts in the attitudes of the society—modernist architecture continues to be relatively unpopular.

In addition, there are discouraging developments in heritage protection itself on the national level. The new head of the Heritage Protection Board does not seem to value the work of Estonian architects from the late Soviet period. In the wake of the war in Ukraine and with support from her political partners, she has begun to actively fight against monuments from the Soviet period. Several of these monuments have a high artistic quality and modernist form. Instead of demolishing them, we should handle them in a more intelligent way, by musealising them or depoliticising them with the help of information boards. Whether it be a Soviet-era building or monument—bulldozing it does not remove our troubled history. What it does remove, however, is artistic value, interesting space and an opportunity to make peace (or truce) with history.

A single truth or conciliatory space?

Preservation of modernist architecture and also monuments is largely dependent on the maturity of the Estonian society—on whether we are able to appreciate the diversity of the spatial culture that has developed in the course of all the twists and turns of history. The other and sadder option is to politicise the preservation of culture and heritage even further and start purging it based on not its inherent value, but rather the labels ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, ‘familiar’ and ‘foreign’. What is right and familiar will be conserved; what is wrong and foreign shall be bulldozed. In the end, we might be left with nothing but barn-dwellings and folk costumes. A more open-minded and empathic stance on the architectural heritage of recent history—including modernist architecture—would also give us significantly more ideas on how to deal with the current challenges in spatial culture. I believe that modernist space has a strong society-building potential—it teaches us how to live together side by side and take each other into account.

CARL-DAG LIGE is an architectural critic and historian who studies and works as doctoral student/junior researcher in the Estonian Academy of Arts.

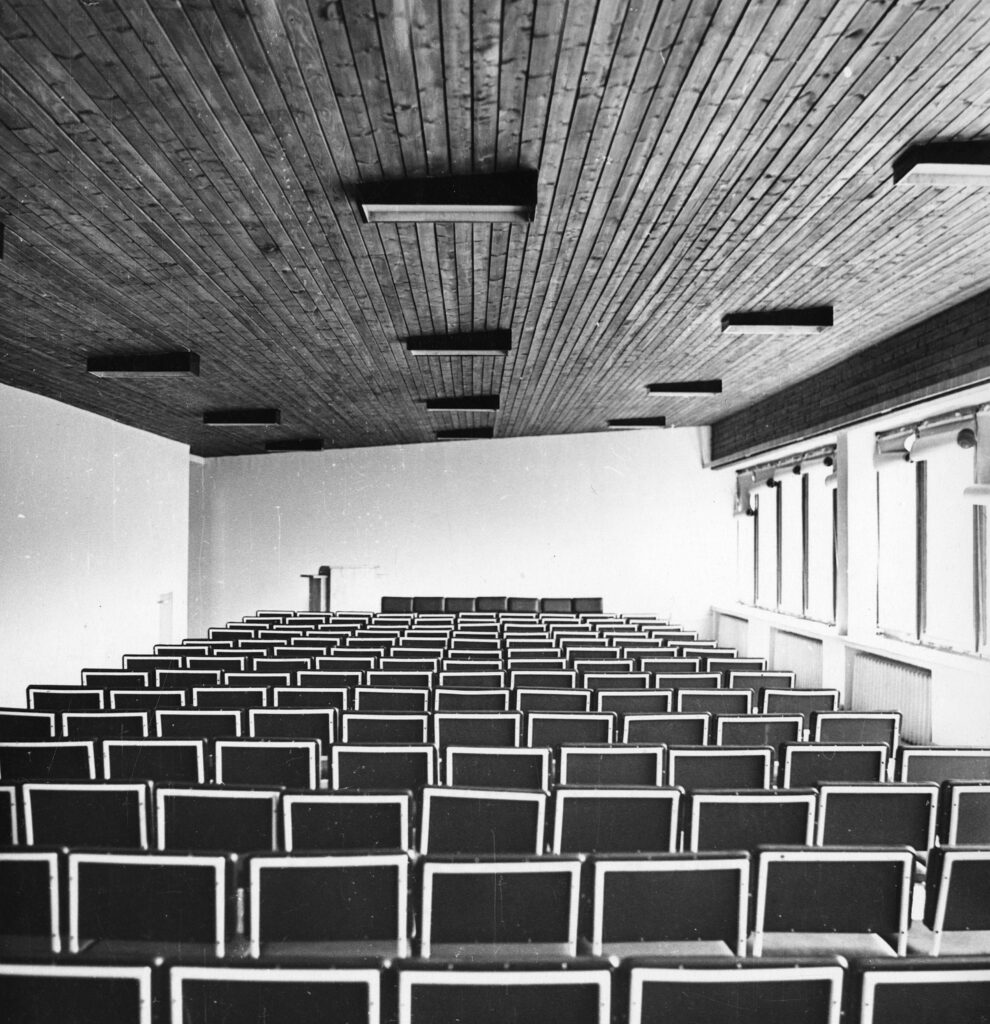

HEADER: The auditorium of Tallinn City Hall. Architects Raine Karp and Riina Altmäe, interior architects Ülo Sirp and Mariann Hakk, 1980. Photo by Henna Mikkilä

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 See, e.g., the expert assessments commissioned in 2020 to designate valuable single objects and buildings for the general plan of the city centre of Tallinn: ‘Kesklinna linnaosa üldplaneeringus väärtuslike üksikobjektide(-hoonete) määramine’, accessed August 24th, 2022, https://www.tallinn.ee/et/kesklinna-linnaosa-uldplaneering/kesklinna-linnaosa-uldplaneeringus-vaartuslike-uksikobjektide-hoonete-maaramine.

For the most comprehensive overview of 20th-century architecture in Tartu, see: Egle Tamm, Tõnis Kimmel, ‘Tartu linna kaitsmata ehituspärand 1870–1991’, accessed August 24th, 2022, https://register.muinas.ee/ftp/XX_saj._arhitektuur/maakondlikud%20ylevaated/tartumaa/Tartu.pdf

2 Iida-Mai Eenmaa, ‘Pakosta ei pea linnahalli konstruktsiooni uuendamist mõistlikuks’, ERR, accessed August 24th, 2022, https://www.err.ee/1608579298/pakosta-ei-pea-linnahalli-konstruktsiooni-uuendamist-moistlikuks.