The Curated Biodiversity landscape laboratory in Tartu has organised six experiments so far. Running a small operation, we might not be able to change the world at the snap of a finger, but we can start with what we can handle.

Increasing biodiversity is actually not difficult at all: most of the best methods include doing nothing at all, letting things be, not organising, leaving things unattended, turning a blind eye. Interestingly, interfering less is what turns out to be the most difficult thing for humans as from early childhood we are programmed to desire to change the environment around us. It was not long ago when no one (who was not a botanist or ecologist) knew that the grassland behind the village is biodiversity. It was simply considered a natural part of the environment. Corncrakes on summer nights, yellow jackets in July, and car grilles packed with bugs after a night drive were considered equally mundane. Biodiversity has for long been on a downward slide: according to studies performed in Germany, measurements made over a period of 26 years indicate that the biomass of insects has declined by 75%. Moreover, these measurements were made on wildlife preserves where the chances of success for many species are considerably higher than in environments that have succumbed to man’s desire to control: cities, villages, agricultural landscapes.

We know that biodiversity is on the decline everywhere and that changing that tendency must be a global effort. So, what are the chances on local level to draw breaks on this trend? Does our modest personal resistance count, and if so, to what extent?

All global change has started at local governing level—many small decisions eventually amount to a large impact. Mending things needs to be approached with a similar mindset—by starting small. By acting locally in our cities, we cannot (initially, at least) change anything globally, but we are able to deal with issues such as rainwater, degradation of soil, loss of biodiversity, even extinction of species.

Flooding caused by torrents of rain has become an increasingly visible concern that is understood even by people who know little about the subject. The amount of rain that falls in one storm has increased and the sewage system is unable to manage it. At the same time, there is much hard surface cover in cities, and each year, more and more area is covered with asphalt or other similar material, whereas an equivalent amount of area is not released from hard paving. The best absorbents of rainwater are biodiverse semi-natural grasslands and green areas. The roots of plants that have had the chance to grow naturally go deeper into the ground, aerate the soil, and improve its quality as well as its ability to absorb and retain water. Ditches, pits, and other surface indentations such as puddles are all equally good at managing rainwater, channelling it, as well as providing habitat, food, and drinking water. Canalised rainwater is a wasted resource.

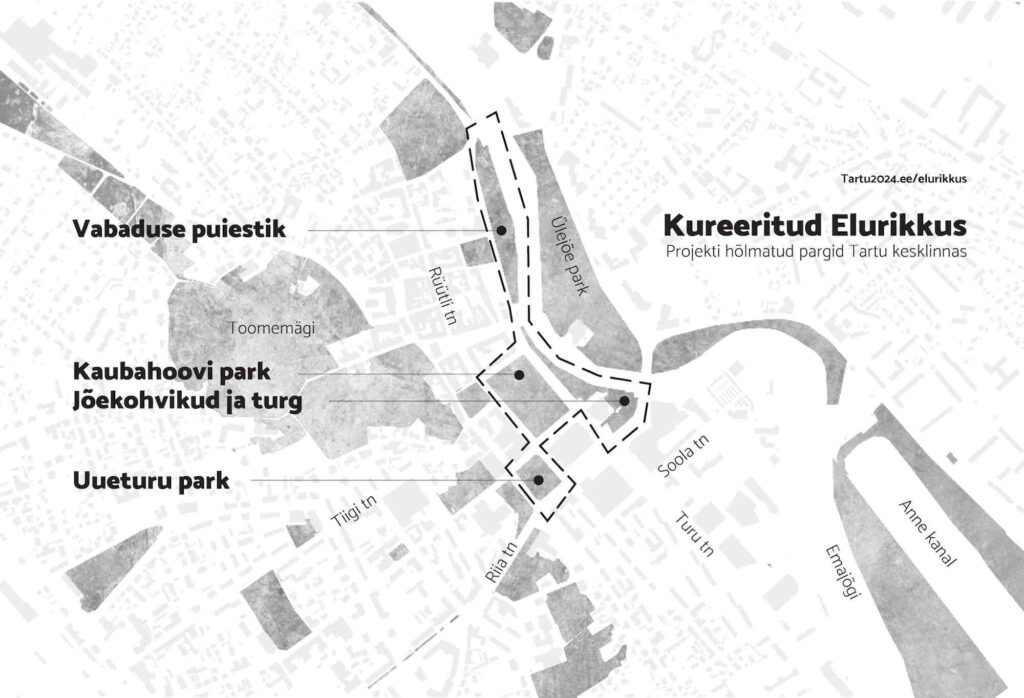

Curated Biodiversity is a group of women that has come together to raise biodiversity. We operate with parks in Tartu city centre, where we test out various methods to improve biodiversity. Prior to all activities, scientists from Tartu University and the Estonian University of Life Sciences counted people, insects, and plants in the parks, and the census will be repeated in a few years to retrieve a possible percent of increase of biodiversity in the areas.

So far, we have tested the following six methods for their applicability to raise biodiversity, some of which have been combined.

Not mowing — ‘Do less’

The first spring grass cutting in 2020 was done in May. After that, we selected areas in the city centre parks where nothing was mown for the remainder of the summer. Information boards were installed near the unmown areas with descriptions (in Estonian, English, and Russian) on the actions being taken, the reasons behind them, and how it all benefits society.

One rather simplified misconception seems to be that if a lawn area is left untended for an extended period, it will immediately become a blooming field of flowers. That is not the case, at least not in the sense people think. Regular lawn grass sustains only a few species (about 5), the lawn is diligently fertilised, moss control is performed and other types of activities which are at odds with natural selection are carried out. Therefore, by simply leaving the grass unmown, grasses grow tall and blossom, dandelions and other plants that have managed to adapt to the mowing, flourish. For the ecosystem in that area to become something else will require more than two or three summers.

We did unexpectedly well in Tartu: since the lawn which we ceased to mow had not been fertilised for a long time, yarrow began to flourish a month after the changed mode of maintenance, which reconciled the more demanding citizens with modern planting and landscaping techniques. The yarrow had been quietly lying dormant in the soil, waiting for its time, and was now able to take advantage of the favourable conditions. Blooming patches of yarrow became so popular that people would go and sit among them. The typical argument against semi-natural habitats, the fear of ticks, was not apparent. In addition to yarrow, some surprise visitors appeared in the mix, such as certain bellflowers. In addition to the census carried out by scientists from Tartu University, we performed our own little experiment where we counted clearly visible species in the mown grass, and in the unmown patch next to it. The difference in ratio was multifold in favour of the unmown areas.

At the end of August, grass was cut from the unmown areas as well. Since the autumn was long and warm, grass was regularly cut at other locations, but left intact on the experimental patches so that they managed to partially blossom one more time. This spring, grass was cut in the entire city once—in May, after which we have continued our experimenting with the patches and extended the unmown areas to Vabaduse park.

A strip the width of the mower is always mown on the curbside between the footpath and the flora in all experimental areas. This ensures that the people who wish to not encounter vegetation are able to safely tread on the path, simultaneously signalling that the unmown state is intentional and systemic, not random.

Meadow mat— ‘Roll out the carpet’

A meadow mat or a pre-cultivated semi-natural biome holds an advantage in urban space in temporal terms. People tend to be impatient with semi-natural biomes: they expect them to be ready on the spot, much like a house or a planted flowerbed. Formation of a biome, however, takes time—at least two, mostly three vegetation periods. Furthermore, the interim growth period is not very welcomed by people since annual root weeds get lost in the mix before the dominant biome takes over. Nature manages these phases beautifully and the weeds will not prevail, but the process takes time. Meadow mats are pre-grown, the weed period is past, the biome is three years old. They are rolled out like transplant grass mats and the following year (or the end of the same summer, depending on the time), they will blossom. They can be transplanted in unmown state as well in which case the effect is immediate.

That was the option we implemented in Tartu city centre, on Car-Free Avenue. Mats in full bloom were peeled off the ground and initially transferred to planting boxes, later permanently to the park. Since meadow mats are extremely biodiverse, we co-operated with children from Tartu Nature House to mark many of the plants with name signs. There were three biodiversity tours in the programme of the aestival Car-Free Avenue, during which we took people for walks to the meadow mats and the unmown test patches, introduced our working principles, activities, and future plans. The tours turned out to be unexpectedly popular and the attendees were largely like-minded people which indicates that the paradigm shift in urban landscaping is slow, steady, and irreversible.

Urban meadow— ‘Let’s take it from the top’

The most thorough intervention is planting a new meadow from scratch. We started by peeling off a ten-centimetre-thick horizon layer of grass and soil. There are plenty of methods how to establish meadows on rather fertile soil: deep ploughing, after peeling or ploughing sand or other type of less fertile soil is mixed in with the existing soil, or completely new soil which is less fertile and more appropriate for meadow or grassland species is introduced to the area. In our experiment peeling revealed that the dirt underneath was appropriately not very fertile, so we were able to sow seeds right after aeration. Once the top earth layer is removed, the concentration of so-called weed seeds (a degrading moniker given by humans with a rather agricultural, productivity-related background) is automatically smaller. Some will always remain, the wind and birds spread them, but we were able to avoid mass populations.

We decided in favour of autumn sowing. Experiments so far have revealed it is more efficient: the seed falls into its place of growth at the same time as it would in nature and even if it germinates the same year (in a warm autumn), that will not harm the plant. That type of sowing is in alignment with natural rhythms and the seeds that have lived through the winter hold an advantage in the spring: they are able to start growing as soon as the conditions allow. Meadows founded in the spring, however, are often soft for a long time, machinery cannot access them which causes delays in sowing and the plants miss the natural rhythm.

Thorough communication preceded the foundation of the meadow, including a plea for citizens to bring bulbous plants from their gardens to plant into the meadow. We were specifically interested in plants that have grown in local gardens for long periods, not imported bulbs sold in gardening centres. In all our methods we exclusively use seeds of meadow plants machine- or manually harvested in Estonia. Therefore, we were keen to follow that principle with flowers.

The residents of Tartu came along with our plan. On the day of planting, we had gathered many crates of wild tulip, crocus, daffodil, glory-of-the-snow bulbs and about ten citizens who came to help us. Together we planted the bulbs in the peeled and aerated meadow, sowed the seeds and closed the surface back up. The end phase of the work revealed what is commonly considered unpleasant about biodiversity: a flock of pigeons landed on the freshly sown and rolled-up meadow and began indulging in the precious seeds, worth a good amount of money per kilo. In nature, it would be quite difficult to successfully get to such seeds—they do not come in cleaned-up form, ready to be pecked and the bird must go through quite a lot of trouble to crack open the seedpods. Since fighting off the pigeons would have been pointless, we considered them part of the biodiversity phenomenon and let them be. The spring has shown that the birds ate up a good portion but there was enough to sustain the meadow.

The seed mix mostly consists of perennial species, and some annual bloomers. Among others, we sowed clustered bellflower, cornflower, wood avens, blueweed, birdsfoot trefoil, sticky catchfly, etc.

Deadwood — ‘Leave it’

Several trees in Vabaduse park (commonly known as Kalevipoja park) had withered in light-deprived conditions and/or illness, and the urban dendrologist’s assessment was to remove the trees. We chose the spots in the park where the felled tree trunks that would be taken down in their entirety (smaller branches roughed down and bigger ones trimmed down to a certain length) would be placed. Deadwood is the main provider of habitat and food for very many species (insects, mosses, fungi). Adults can lie down on the supine trunks; kids can climb and play on top of them. The trunks were placed in locations where they were visible from a distance and enabled views of the park for the people sitting on them.

Vabaduse park is home for one of the largest colonies of rooks in Tartu. During the cutting of trees their nest trees were left intact, and the works were finished before their nesting began to not disturb them. The trees designated to be taken down were additionally inspected by a bat specialist who assessed one of the weeping willows to be a significant shelter for the bats (the tree warps above the river and is thus an important landing and hangout site for the vesper pond bats). The weeping willow was saved, only the dried branch hanging above the footpath was removed.

Branch pile — ‘Nest away’

Branches of the cut down trees were gathered into piles. When assembling these structures in urban environments we must keep in mind that people may not be overly familiar with such remains—they may have seen them in the context of bonfires, but most likely not in a city or a public park where they are intentionally and exclusively exhibited. For this reason, the branch piles were curated and carefully designed, moulded into pleasing shape and structure so the message would be unambiguous: it is not a pile of remains, but intentional activity. Branch piles are extremely valuable providers of habitat for insects, birds, and hedgehogs. Children were among the first to discover them, and successfully adopted them as hideout sites for games of hide-and-seek. We used both thinner and wider branches to build the piles; the more substantial branches can support kids climbing on top of them as well. All branches were interconnected with wire to make the structures durable and static, ensuring their safety for the purposes of climbing as well as eliminating the risk of accidental disassembly.

Urban grove— ‘Seize the opportunity’

The branch piles as well as deadwood were part of the development of the urban grove, but they can be used as individual methods in whatever green area. In our case we were able to join them.

Over the years, the crowns of the trees in Vabaduse park have grown into one another, the park is shady, the undergrowth has become shrivelled, and the shrubs front is entirely missing with a few exceptions. In the springtime, the most gorgeous field of the yellow-star-of-Bethlehem blossoms there, but as soon as the trees put forth leaves, anything below human eye-level becomes bleak. Such dimness and partial dampness which originates from the proximity of the river, resembles the grove forest habitat type. Therefore, biomes of grove forests should be supported there.

In the first stage, as per agreement with landowners, we botanised liverleaf, wood anemone, mountain currant, honeyberry, and other specimens from clear-cut forest areas (habitat of liverleaves). Underwood species would quickly perish in the drastically changed light conditions of the clear plains but in urban parks they were able to get a second chance. In addition, we were given permission to dig up and transplant common hazelnut trees, tall-growing strawberries, rowan trees and bird cherries from Haage manor.

City residents were happy to help with the planting and came, bearing plants native to grove forests: ferns, fragrant Solomon’s seal, lily-of-the-valley. Together, we planted them all.

Curated Biodiversity will further focus on developing the already planted biomes, park projects and cooperation with the residents of Tartu. Focus group interviews and active engagement of the citizens will be continued prior to drawing up new projects.

KARIN BACHMANN is landscape architect.

HEADER photo by Evelin Lumi

PUBLISHED: Maja 105 (summer 2021) with main topic Landscape Architecture!