Space Whisperers from Landscape Studio ALPS 〉 Interviewed by Merle Karro-Kalberg

New Urbanism and Landscape Urbanism 〉 Hannes Aava

The ‘Romanticism’ of Wastelands 〉 Leonhard Lapin

Liberating Wasteland 〉Piret Vacht

Plant Punk and Poetics 〉 Eike Eplik

Young Heart 〉 Interviewed by Anna-Liisa Unt

Weeds 〉 Sandra Kosorotova

My Biodiverse Garden on Hiiumaa 〉 Kristiina Hellström

Green Values 〉 Anna-Liisa Unt, Indrek Ranniku

Carbon Footprint in Landscape Architecture 〉 Mirko Traks

Curating Biodiversity-The Tartu Experiment 〉 Karin Bachmann

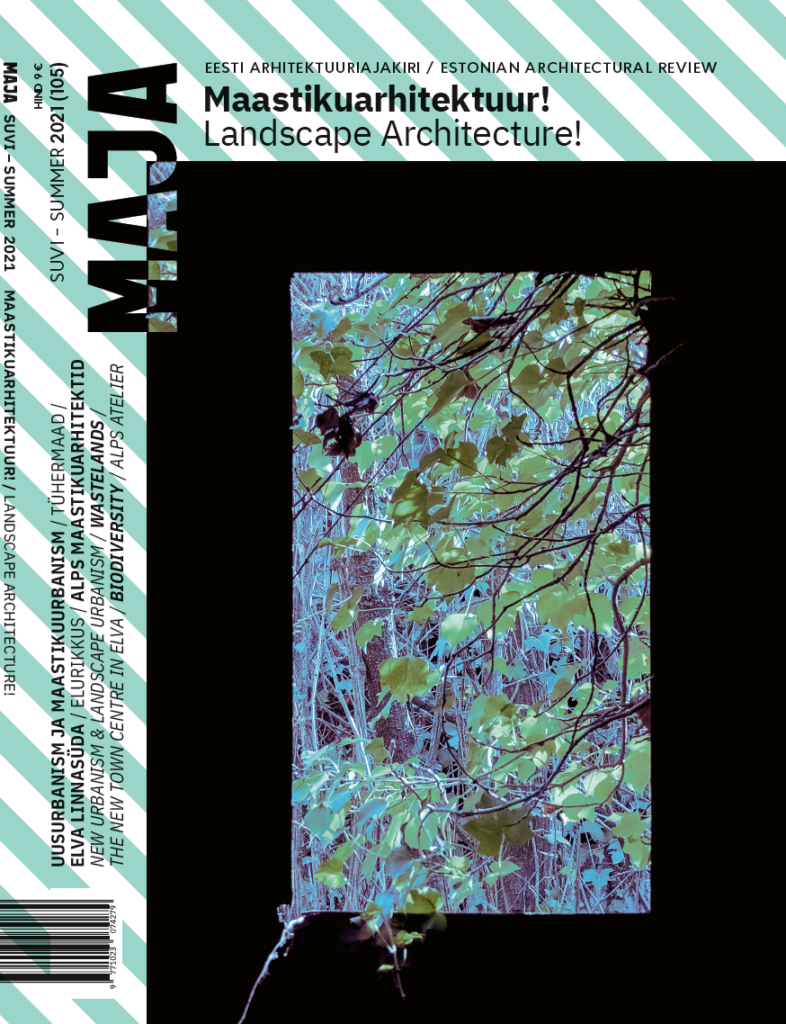

Landscape Architecture!

The summer issue of Maja looks into and introduces landscape architecture. The main question being asked is whether landscape architecture is a mere decoration between buildings or something that can be entrusted with more serious tasks. And, as landscape architecture reveals itself as an instrument for tackling climate change, adjusting society to its effects, and restoring biodiversity―can artistic expression and creative search survive in it as well? We ask how we can solve the great situations and bottlenecks that lie before us so that the creative ambition of landscape architecture could also thrive.

In an age of norms, legislation, directives, injunctions, and other numerically measurable values it would seem that urban nature remains one of the few places whose design and appearance are governed by aesthetic principles. Any kind of rational debate ends immediately as soon as something is deemed ugly, or on the contrary, beautiful by someone. More often than not, things that are considered ugly have many more hidden facets. This is the case with semi-natural habitats in urban space. Bishop’s weed, nettle, and goosefoot are defined as unpleasant, which is why the merits they could bring to a city and the living environment as well as the entire ecosystem are completely missed.

In the tailwind of prevalent thought models urban nature is undeservingly and unnecessarily kept in an insipid state. As a result of simplified landscaping plans, optimal choice of plants from the maintenance point of view, and extensive mowing-cutting, green areas are profoundly lacking in the natural and social versatility that a contemporary urban landscape deserves. Green areas are short of real greenery and there are not enough retreats.

There is cause to be alarmed about issues surrounding biodiversity especially in cities and towns. Outside city limits there seems to be more than enough of the green space, but even here the scales are out of balance. When comparing territories inside and around cities in the same scale, cities tend to have better landscape mosaics, which means a richer variety of space, terrain and species. Extra-urban landscapes cultivated for the production, storage and transportation of food sprawl across broad single-purposed land areas with sole soil cover. Cities are in fact doing quite well: every theme is in constant circulation and the need for, and effect of, change is immediate and clear. However, cities continue to face the same environmental issues from decades ago such as polluted urban air, general loss of biodiversity, and the separation of us humans from nature.

Designing with nature is not a new approach. 1969 introduced Ian McHarg‘s cult work ‘Design with Nature‘ where he formulated the methods of sustainable design for the built environment and substantiated why in designing the urban environment it is necessary to be better acquainted with natural processes and understand how nature functions. 50 years later all these concepts are still relevant, some even seem radically innovative. The 1970s was the decade of rise in awareness of environmental protection; the 1960s’ ecstasy over technological advancement and the space race was replaced by the oil crisis and environmental problems. Likewise, today any debate in any discipline touches upon the concerns of climate change, our ability to adapt, and sustainability. Young climate activists (Fridays For Future) acknowledge the critical nature of these concerns and have sharply brought the need for change to the public forum. Noticing problems, acknowledging them, and a sense of mission to find relief or solutions shows environmental awareness and a critical mind about the future.

Part of the discussion is our dwelling environment in general, part of which is landscape architecture. But, how do you measure the climate neutrality of a landscape? Buildings have energy labels and methods for this purpose. Landscape can not be measured this way, nor would anyone want to. It seems there is a default agreement on the quintessential energy sufficiency of landscape: planting a tree is a positive favour for the environment past which no further thought is invested.

Editor-in-chief Kaja Pae

Guest editors Anna-Liisa Unt, Merle Karro-Kalberg and Karin Bachmann

July, 2021