Does the legal space facilitate or hinder us in turning living environment in Estonia smart and in a smart way?

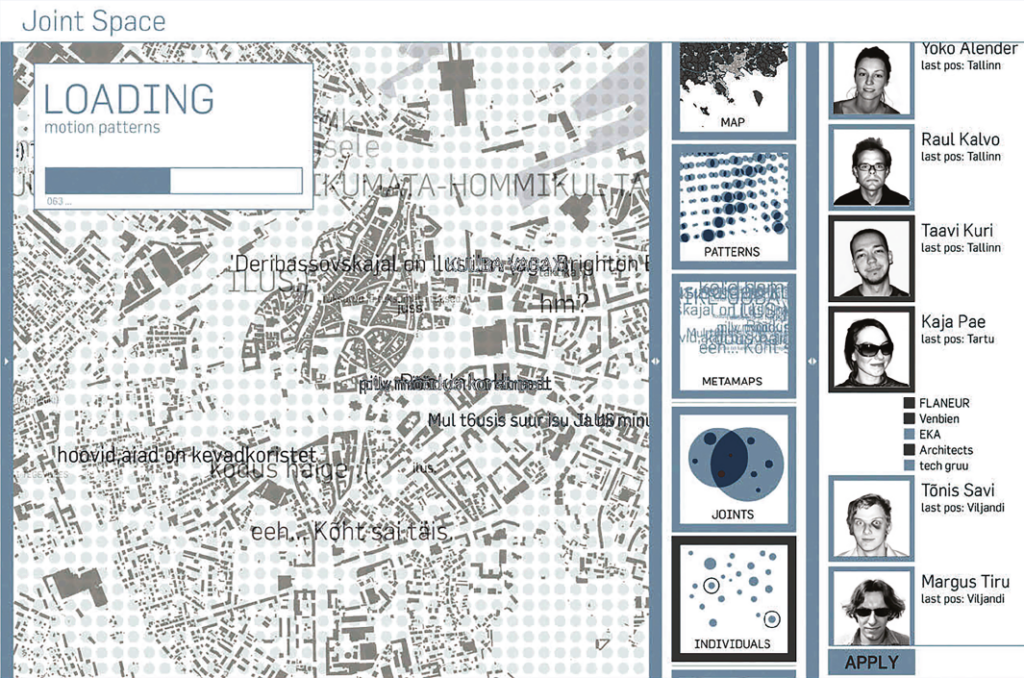

Almost 15 years ago, in 2006 to be exact, we represented Estonia at the Venice Architecture Biennale with the project Joint Space in cooperation with the architecture office Urbanmark, Positium, Tartu University and Estonian Academy of Arts curated by Ülar Mark, Rein Ahas and Kaja Pae. Facebook had already been invented and it became globally available in 2006 together with the so-called news feed. We had no knowledge of Facebook at the time. The application in which the algorithm feeds you the content selected for you began to develop rapidly in 2007, with Yahoo, Microsoft and Google making every effort to invest in the company. Microsoft was the only one to succeed1 acquiring 1.6% of the shares for 240 million dollars. But that was only the beginning.

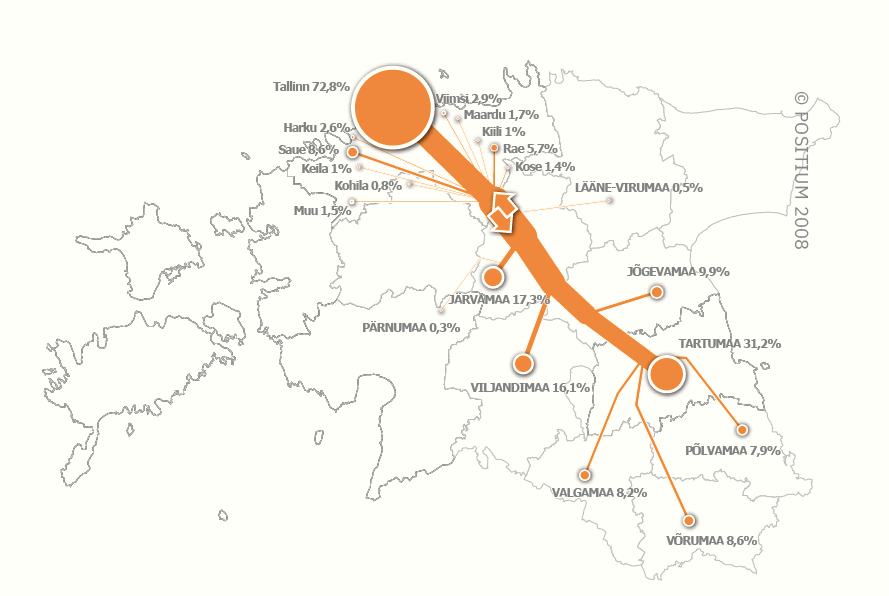

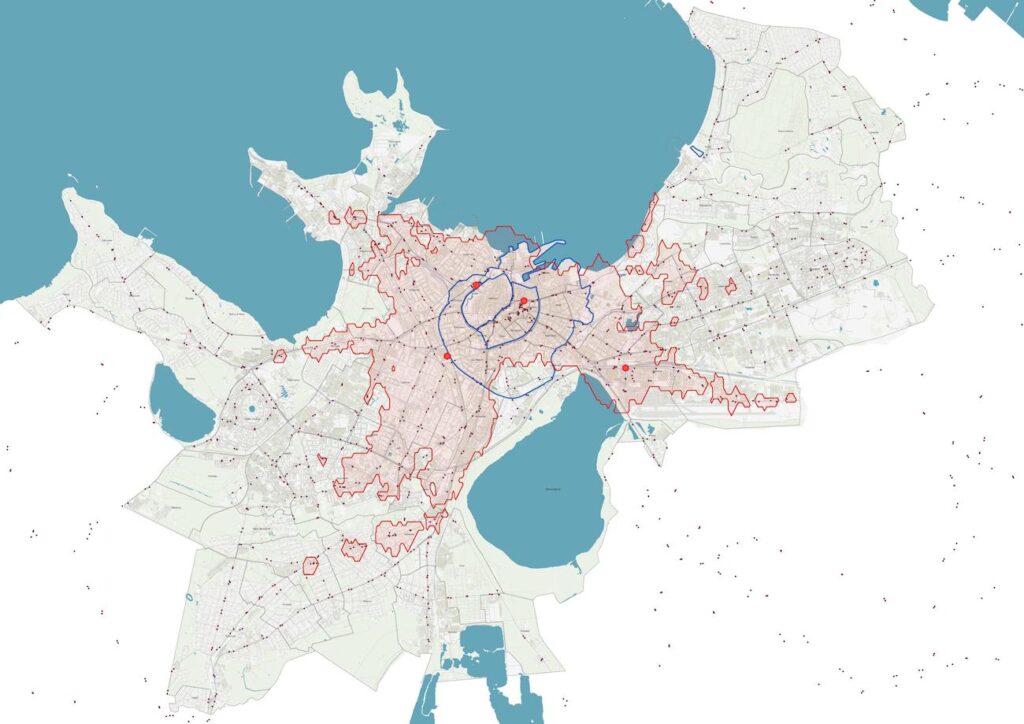

At the time, the Academy of Arts (EKA) was looking for a new location and most students were carrying mobile phones that could be positioned already quite accurately—we understood that there might be something in intertwining the digital and physical space. A number of EKA students allowed us to position them for a month—we asked them to send us location-based messages that were displayed in our map application real-time and thus analysed their routes in terms of the new potential locations for the academy. We had a hunch but we did not quite know why it is good that an application knows where you are and can share something from that place with a selected group of people through your phone–either photos, messages, your location etc. We also studied the bicycle lane preferences among cyclists and the tourist routes in Tartu as well as the daily route patterns of the urban sprawl in Tallinn. At the same time, one of our schoolmates from EKA Andres Sevtšuk was in Venice curating the exposition Real Time Rome of the famous Boston school MIT with Carlo Ratti. We were proud to be among the pioneers as the cooperation with EMT provided us with the means for analysing large quantities of data. The turning point came with the launch of iPhone in 2007 converting phones basically into portable computers that, in turn, provided new opportunities for collecting spatial data (beyond mere positioning). In 2014, young architects Johanna Jõekalda, Johan Tali and Siim Tuksam continued the topic of combined virtual, digital and physical space and the smart qualities of space in the Estonian exposition Interspace at Venice Biennale.

But what is going on outside biennales in the streets, on planners’ desks and legislators’ offices? Can we harness the digital possibilities for the physical space? The intersection of the physical and digital space has provided us with various versions of Bolt and Wolt, bike rentals on the phone, peatus.ee, location-based events, tripadvisor and many other useful applications for adventurers in space. Have they managed to change the urban life more than architects and urban planners through their concurrent designs? How much do we know about the role of data and smart solutions in planning and how can we use data in practice? Personal data have been protected by the infamous EU GDPR regulation for some years already. Where are we with the legislation regarding artificial intelligence, our very own Kratt law? First, we will focus on the question whether the current legal framework facilitates or hinders the creation of smart living environment in Estonia?

WE CAN USE DATA TO PREVENT COLLISIONS OF RECONNAISSANCE SATELLITES IN OUTER SPACE BUT WHAT ABOUT ESTABLISHING A BETTER AND SMARTER LIVING ENVIRONMENT FOR OUR DAILY LIFE?

I first asked the legal analyst of the Privacy Technologies Unit of the Department of Information Security Systems of Cybernetica AS Triin Siil which legal acts regulate the use of data in Estonia?

Triin Siil: ‘Data that can be linked with a private individual are protected at national level with the Personal Data Protection Act (IKS) and in the European Union with the General Regulation of the Protection of Personal Data (GDPR) directly applicable to all Member States. The rules for using personal data are sufficiently clear in case the person has given his consent for their use. It is somewhat more complicated without the consent, as according to GDPR, the Member States have a fair degree of freedom to lay down specific rules for processing personal data in various sectors by law. There are no such special rules in the area of urban planning in Estonia, however, section 6 of IKS does set out general rules for research and historical research as well as official statistics, for instance, for policy-making purposes. In that case, pursuant to articles 25 and 89 of GDPR and sections 29 and 33 of IKS, we probably need to resort to privacy enhancing technologies to prevent undue interference with people’s privacy and other fundamental rights.

IKS and GDPR do not apply to anonymous data, however, also here we need to consider various legal acts—on national level primarily the Public Information Act2 , in European Union law also the Regulation on the free flow of non-personal data3 and the Directive on open data and the re-use of public sector data4. In addition, it might be important to consider also the rights related to databases that in Estonia are regulated by the copyright law and in European Union the Directive on the legal protection of databases5.’

The current debate largely revolves around the anonymisation of data, that is, to what extent is it enough to remove the name or identification code to make the data ‘non-personal’. In legal terms, anonymisation could be defined according to the simplified explanation deduced from recital 26 of the European General Data Protection Regulation. In the given wording, anonymisation means rendering personal data anonymous in such a manner that the data subject is no longer identifiable with reasonable effort.6 According to legal experts, however, there are still various possible interpretations and, for instance, the anonymisation of people’s mobility data is highly complicated.

The most recent fast-growing area in the world of data is thus privacy enhancing technologies that offer a kind of black box service, in other words, hide personal data from the user’s view while still allowing the use of information necessary for analysis. In Estonia, such services are provided by Cybernetica AS who, for instance, conducted the security analysis for the COVID-19 exposure notification application Hoia but also proposed a solution allowing to prevent the collisions of reconnaissance satellites of various countries without knowing each other’s location.7 There is also an ongoing EU project allowing privacy enhancing technologies to analyse the mobility between people’s main place of residence and other destinations without revealing individuals.

PUBLIC SECTOR AS A CLIENT AND A COORDINATOR OF LOCAL LIFE IS THE POTENTIAL CREATOR OF A SMARTER LOCAL GOVERNMENT OR A SMART CITY

I asked two experts Margus Tiru (geographer and chief data officer at Positium OÜ) and Kristi Grišakov (urban planner, Tallinn University of Technology) if the current legal framework enhances the planning of smarter living environments or rather hinders it, and if so, how?

Margus Tiru: ‘I think that Estonian legislation favours the use of certain type of data while doing less so in case of others. There has been considerable development in terms of various open data, the (relative) openness of national data and the standardisation of databases, including national registers (X-Road) and others. These are used for public purposes, in research as well as in the private sector. The limiting factors in my opinion include the restrictions on the use of personal data and the interpretation of the law. GDPR and other laws protecting personal data are definitely a privilege for EU citizens as (at least in theory) they should protect us from the direct misuse of data. Unfortunately, the self-same freedom in interpretation can also be a considerable restriction to the use of the data for the benefit of the society. GDPR basically allows the use of data for statistical and scientific purposes, however, there is considerable leeway for interpretation. It is not clearly provided, for example, how the mobile positioning data could be used in planning, mobility analyses, research, etc.’

Kristi Grišakov: ‘There are definitely requirements that can get in the way of smart living environments, for example, the parking space requirements or the proportion of green areas that does not consider roof landscaping. A serious problem in the parking study of Tallinn was posed by the new Apartment Ownership and Apartment Associations Act that considers parking spaces as a part of the apartment ownership and thus prevents the contemporary cross-usage of parking spaces. Various standards should be recommendations by nature, however, they are often interpreted as requirements (as a law), for instance, the urban street standard that is not based on the contemporary principles of cross-usage and multimodality. Then again, the problem does not necessarily lie in laws but in the conformity of public officials and other actors to settle for a legally safe solution.’

Are the specifications of the Personal Data Protection Act (so-called GDPR concessions) sufficient for research and statistics to allow the use of necessary data in designing living environments?

Margus Tiru: ‘When we talk about using the data of people who have given their consent, then the legislation, in my opinion, is clear and sufficient. The rules for using personalised data are understandable and serve their function of protecting people’s privacy and personalised data. The main concern for researchers and other analysts is conducting the study with a sufficiently large sample, in other words, getting the consent of a sufficient number of people for the research. The problem is in the use of big data that are statistically much more reliable than samples, similarly faster and more accurate. However, the legislation does not clearly provide the rules for using such data without people’s consent. Similarly, the private companies consider this information (e.g., mobile positioning data) as their property and conduct respective analyses without revealing the methodology—so it is impossible to assess what the analysis reveals or how to check it. In my opinion, the state should adapt the law for the use of particular data so that the way the data are used is clear and secure without decreasing their value and revealing personal information on the people. So that the use, processing and analysis of data would follow some basic principles and perhaps it could also define who can process the data (e.g., Statistics Estonia, universities).’

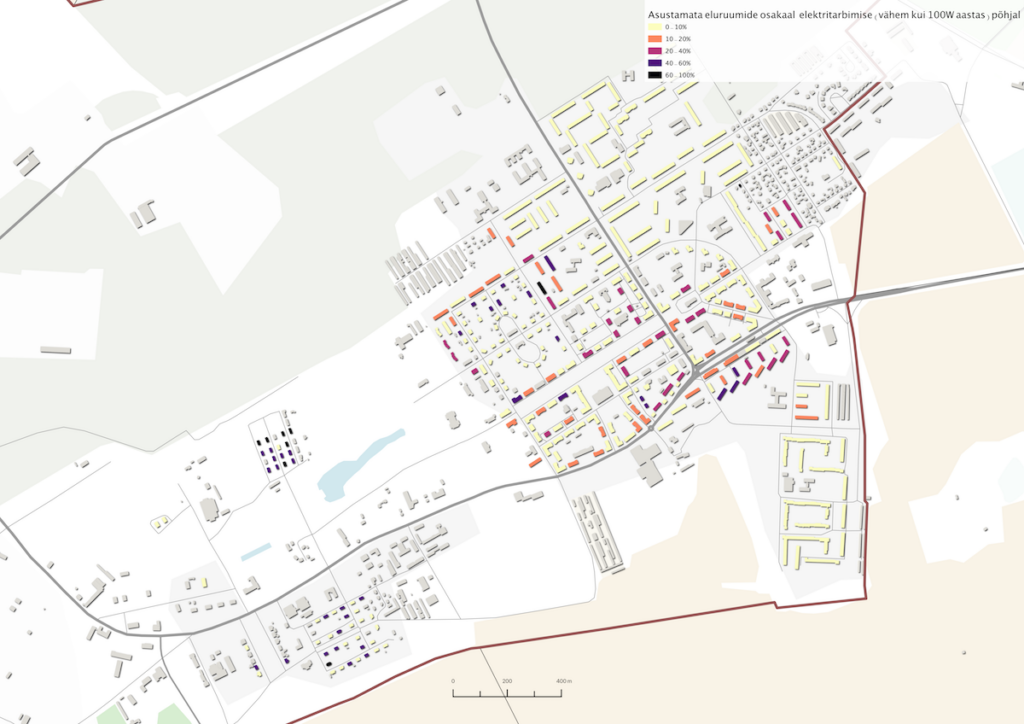

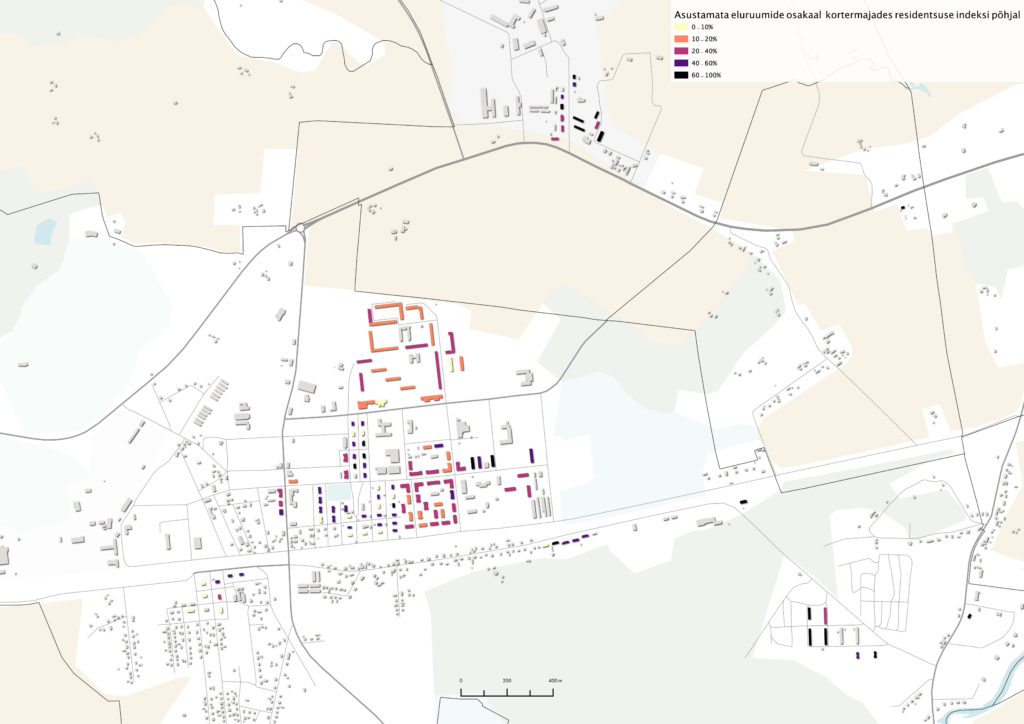

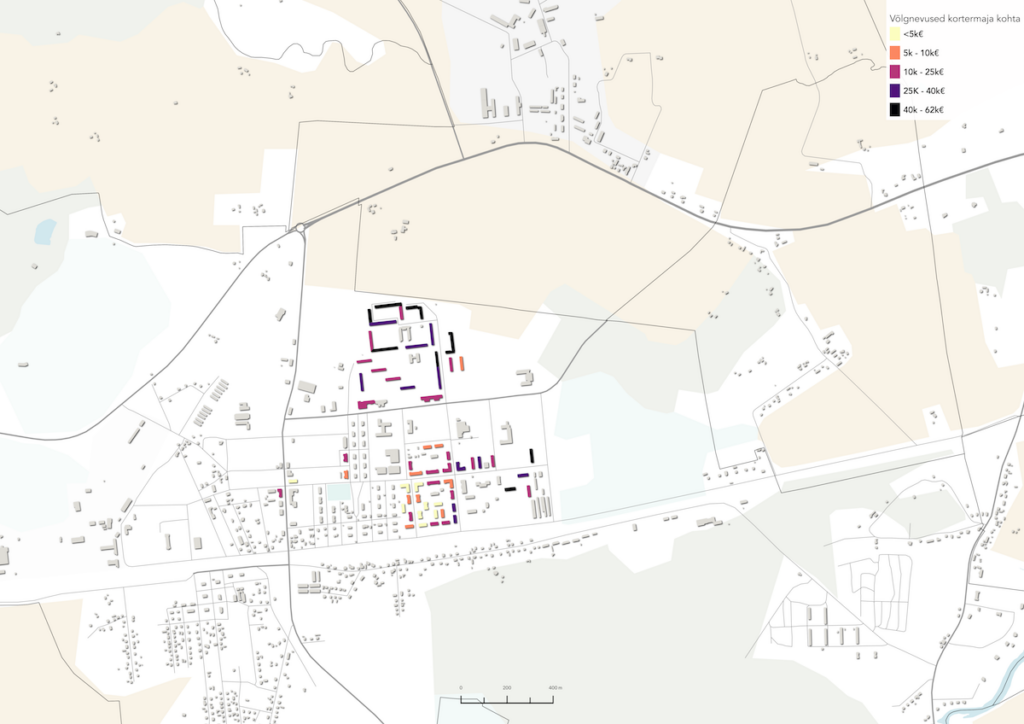

Kristi Grišakov: ‘The closest contact I had with the Personal Data Protection Act was in the pilot study for the Ministry of Finance regarding the half-empty apartment buildings. Although in case of apartment buildings, we can analyse the occupancy of apartments on the basis of data, the personal data protection prevents us from analysing the occupancy of smaller residential buildings (with 1–2 apartments) based on location (on maps). This is problematic for local governments with a large proportion of buildings with 1–2 flats, as occupancy cannot be analysed on the basis of data and they should rely on fieldwork making house-to-house inquiries. I doubt if most local governments can or want to do it. Thus, it is currently impossible to get a comprehensive map-based overview of the consequences of spatial shrinking.

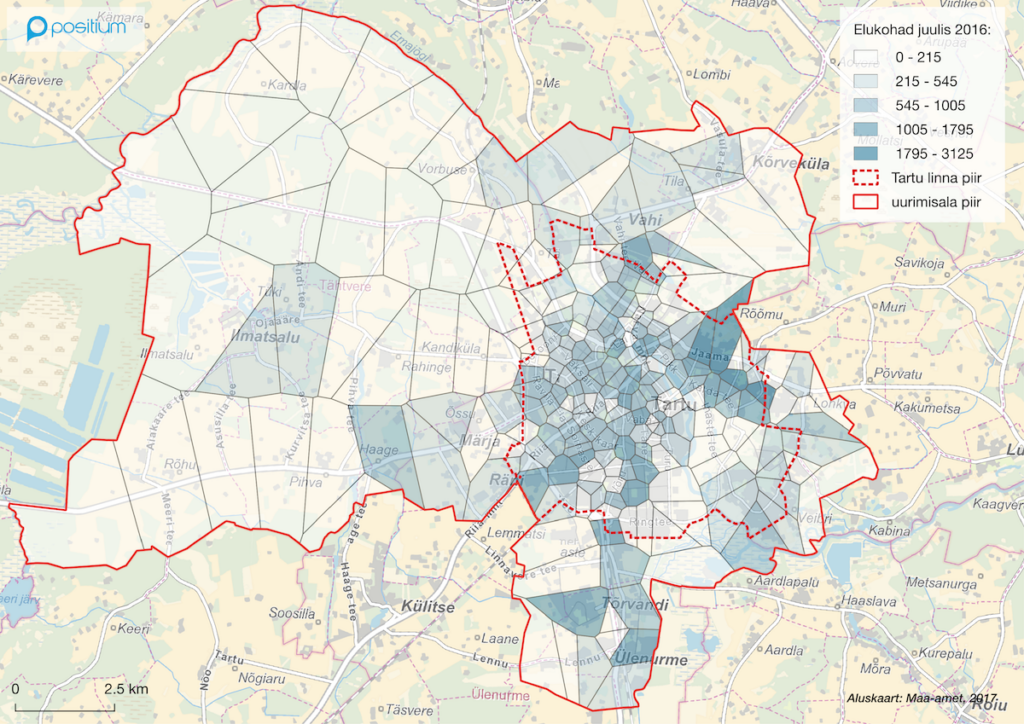

Secondly, in the same pilot study, we also attempted to analyse residents’ change of address. What are the types of buildings that residents have moved from and to in the past ten years? The aim was to establish if the type of a building affects people’s moving. Again, as it was considered sensitive personal data, we requested data from Statistics Estonia (for a fee) that we could use only on-site in the Statistics Estonia office, where the given service is unfortunately rather primitive. Eventually we could analyse resident mobility only on the basis of an Excel table and not with GIS map software. As a conclusion, I can say that although the approach proposed by us is relevant and provides new information on people’s preferred place of residence, such analyses can be conducted in the future only in case the quality of the workstations at Statistics Estonia improves considerably or the analysis is commissioned directly from the Statistics Estonia.’

Could you give examples of how the public sector has used such data in the planning process with good results?

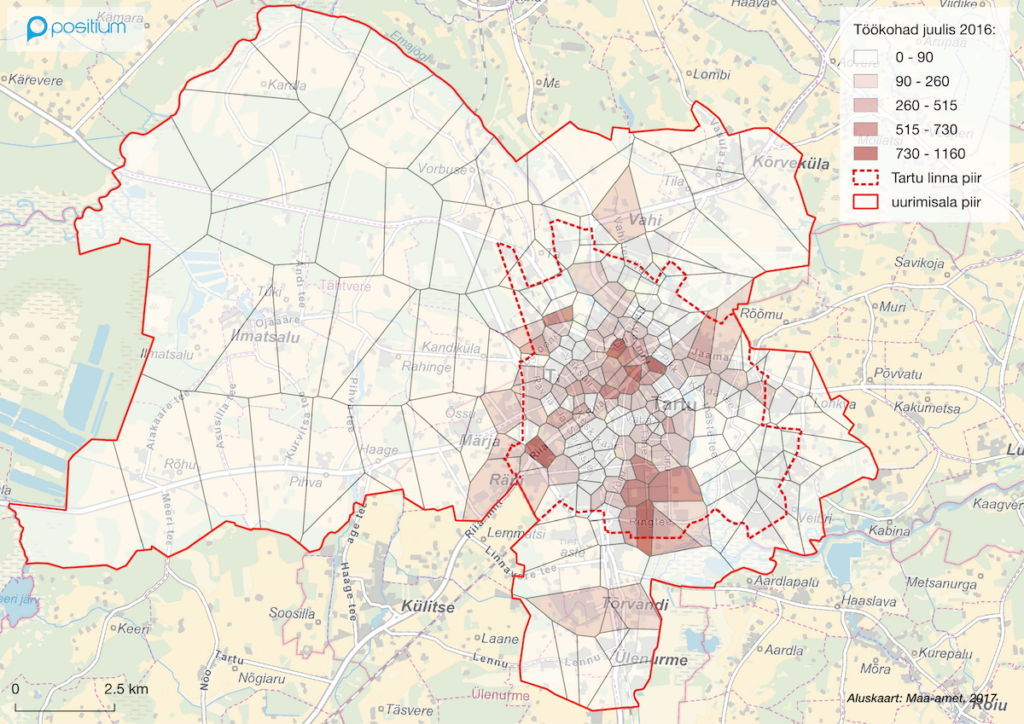

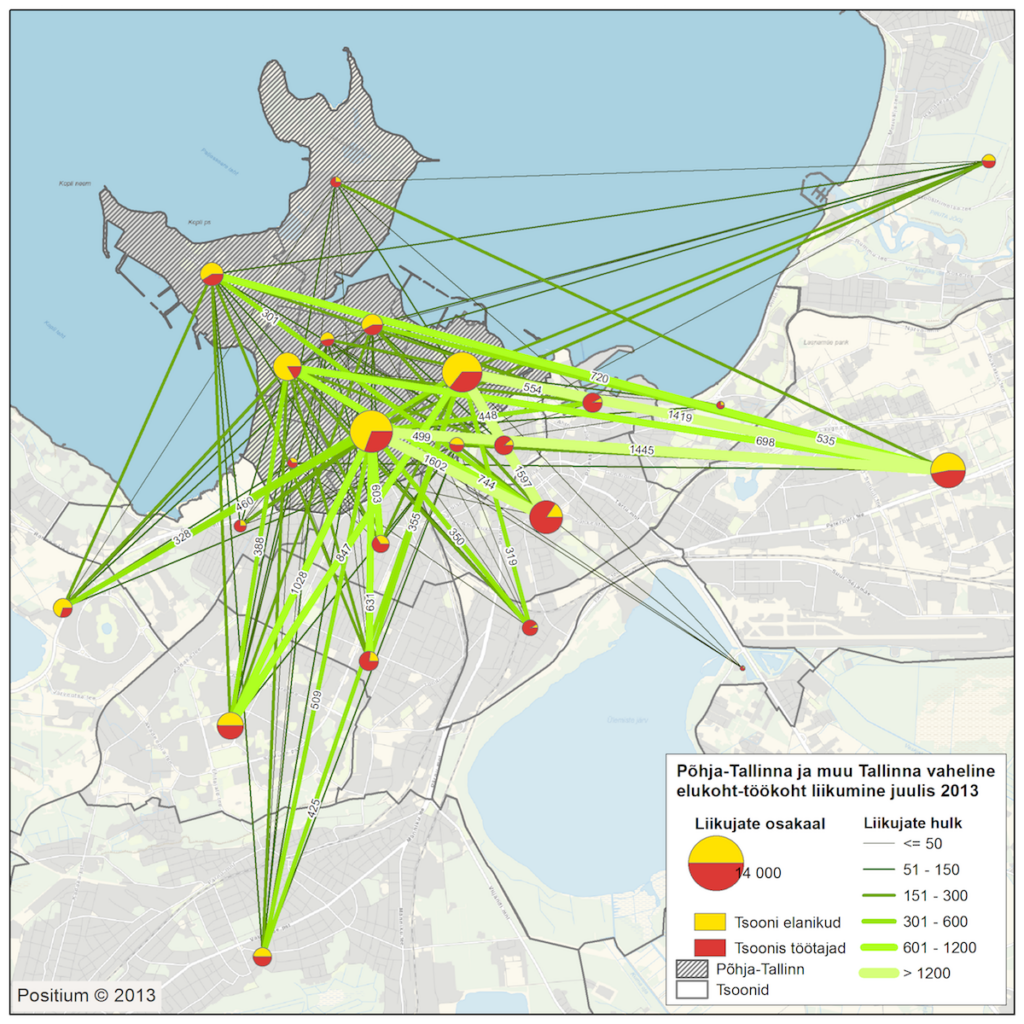

Margus Tiru: ‘I can say a few words about the use of mobile positioning data that have been successfully used in several projects, for instance, the planning of Tartu ring road and the road section in Mäe, similarly the renewal of the public transport lines in Tartu.’

Kristi Grišakov: ‘My most positive example is the above-mentioned project for the Ministry of Finance that aimed at experimenting with the various methods of the data-based approach. When we usually conduct such studies, clients have relatively low data awareness. They wish that data be used but often they do not realise how much time is spent on collecting and cleansing data and also on relating them to locations (space). It is quite common that some local governments do not have an overview of all the data collected and there is no agreed format for data collection either.

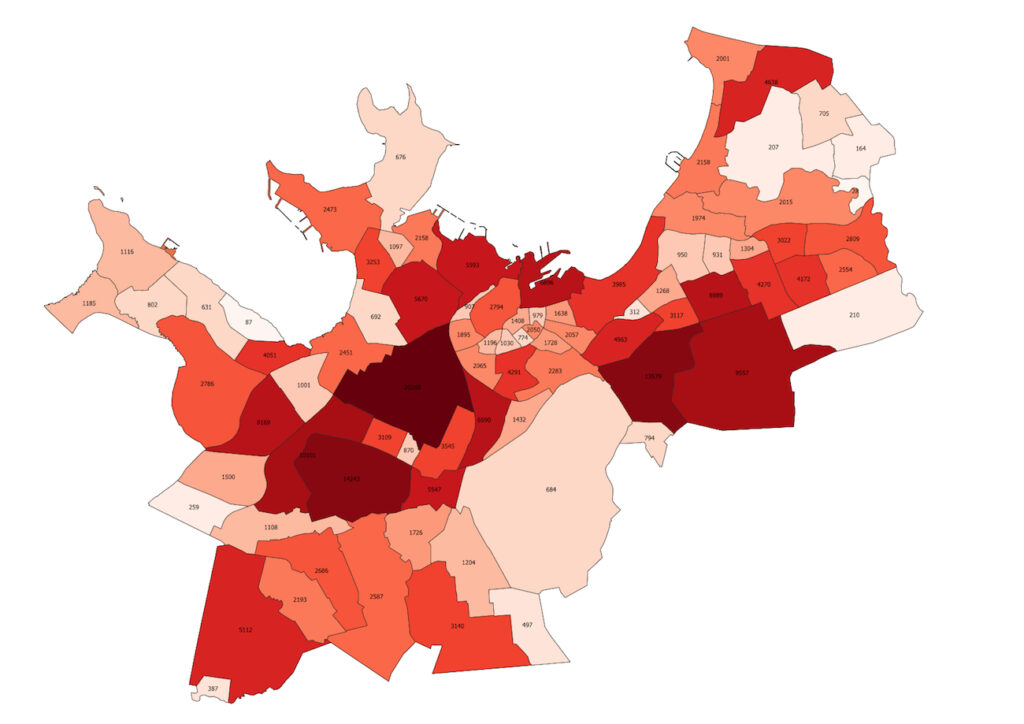

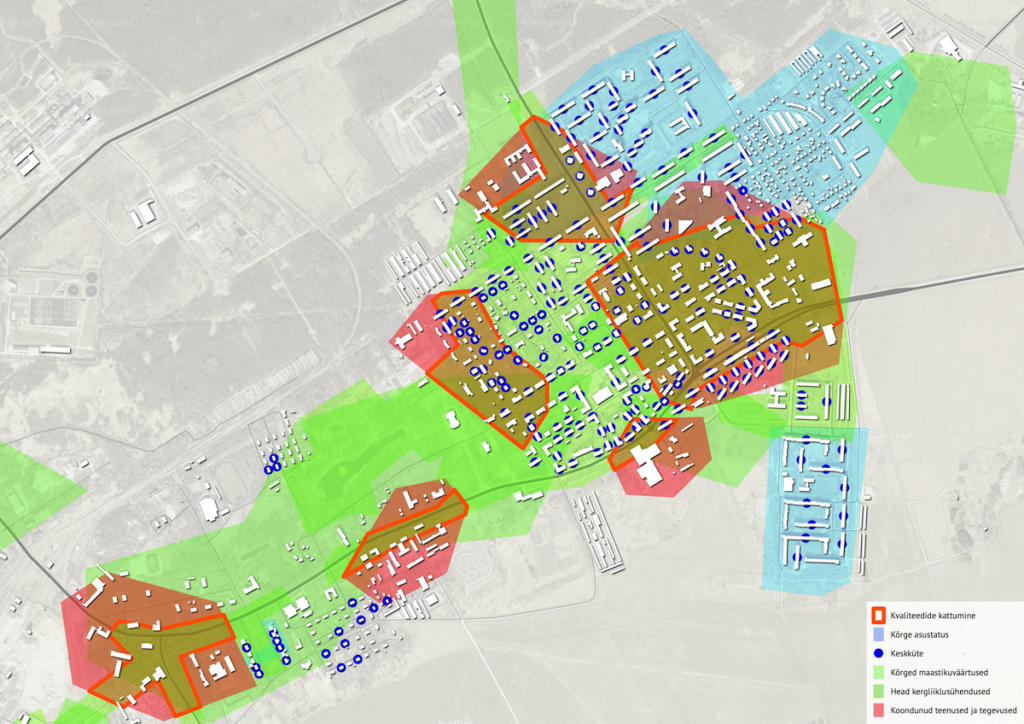

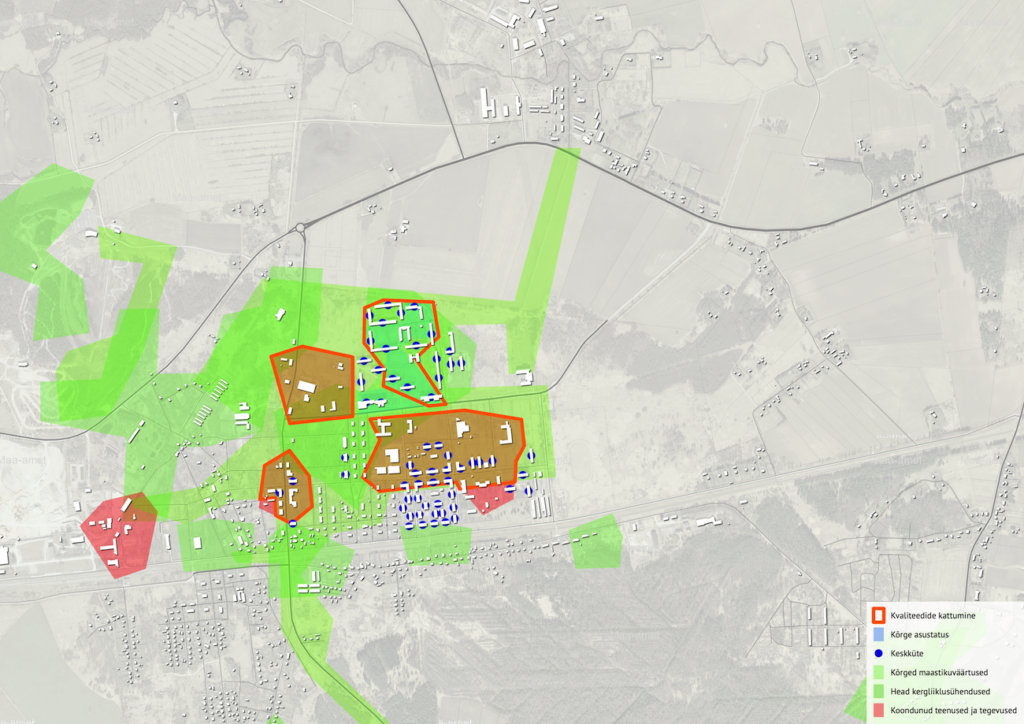

In case of Tallinn, for instance, we have GTFS data allowing us to analyse and monitor public transportation real time. This could be used for various map applications with the current coverage of public transportation allowing to make strategic decisions on where we have ‘good’ public transportation and where not. We proposed in our study that parking norms be decreased in areas with good public transportation coverage (for example, you can get anywhere in the city within 20 minutes). This was just one of the proposals but the city could provide a number of data-based tools that could simplify the compliance with strategic principles and help to solve disagreements with developers.’

Do you think that urban planning and living environment design in Estonia are sufficiently research-based and make proper use of contemporary means?

Kristi Grišakov: ‘In my opinion, this is highly individual. Most people think that data analysis is completely beyond them. When we conduct our analyses, we usually present only the relevant aggregated maps as data seem to confuse people and they cannot make their own conclusions. They want us to say what we conclude from them (what is our interpretation). Data analysis already plays an important role in the education of the next generation, however, the older generation still seems to rely on experience, their gut feeling and other non-scientific categories. It does not mean that they cannot get it right sometimes. However, data-based results tend to be believed more than the same statement without the data. As most people cannot analyse the data themselves, it also requires that they trust the researcher or other specialists talking about the results.

The public sector still has a long way to go before they have data-based tools for the improved planning of space and mobility. There are a lot of data that are not even collected at the moment, and there are data that are collected but not used. In the context of data usage, it is important to understand that data can only reflect the current situation. Strategic goals for the future still require political will and decisions. Data can only show what is happening at the moment. Data cannot unequivocally state that this or that must be done in order to achieve a different kind of future.’

The discussion with two specialists working in the field allows me to conclude that we have not quite comprehended what kind of data we should collect and we do not dare to use the ones we have either. The legislative problems are not so much connected with the data and their use as with the fact that some of the laws do not consider the new reality marked by cross-usage and sharing economy. In addition, immature practice is liable to the risk of so-called scientific laundering–all data systems can be sabotaged in a way that yields the desired results. The result depends on the particular questions and prerequisites. For instance, if we include the estimated growth of traffic in the traffic modelling system, the result will feature wider streets with increased capacity. The given result, in turn, is presented in a way that concludes that the only right solution is to build a wider street with the same modelling result presented as evidence. It is difficult to dispute such selectively targeted research results. The problem primarily lies in the objective and vision set for the planning and its underlying values—in case the focus on people, cohesion and sustainability (if these are considered in the first place) is not accompanied by smartness, innovativeness and flexibility, we cannot expect them in the results either.

KRATT LAW AND HYPERLOCAL LIVING ENVIRONMENT

In order to explore the future of the intersection of data and planning, I had a discussion with Marten Kaevats—an architect working as the digital advisor at the Government Office. I asked him about the future of the legislative framework related to data.

Marten Kaevats: ‘The set of Kratt laws should be proceeded by the parliament next year and we expect it to result in considerable changes in the legislation, primarily in terms of regulating the legal issues regarding artificial intelligence. One of the key issues is algorithmic responsibility. Examples from our future reality in need of such regulation include self-driving systems, vehicles, healthcare advice robots, algorithmic proceedings in the public sector etc. In terms of legislation, the United States is and Estonia could be a pioneer here.’

What will be our role in designing smart spaces? The key principle in Estonia and in Europe at large is that everyone is the master of his data, that is, he controls his data and either gives or does not give his consent to use them. This may lead to a situation where the living environment is largely shaped by people who have, so to speak, given their data to the service of the society. Rooted in advertising, the principle of hyper-locality means that you are served/offered something that you have previously shown interest in. In terms of space, it could lead to a situation where everyone can decide on the extent to which his data are used, and consequently the smart environment around him can react respectively. The book The Stack by Benjamin H. Bratton presents the theory of a high-definition and low-definition citizen–the latter encloses himself from the state into complete privacy thus in a way also excluding his impact on the development, while the former is a proto-hipster who directs the development with his behaviour and thus acts in a so-called fully customised urban space. That would constitute a possible democratic alternative to our current slow planning processes.

The most important thing in the digital, physical as well as legal space is obviously trust—whose data will actually shape the future urban spaces? The composition of the legislative body is determined by people who vote. Will our future living environment be shaped by everyone’s behaviour or only by those who allow their data to be used? In that case, the next question on the meta-level would be: how to build architecture at street level based on trust–trust between the data collector (that could also be a sensor), data user (private or public sector) and data holder (resident) in a situation where we are the first generation to be beaten by the previous one in intelligence?8

This brings me back to where we were in 2006. As students of architecture, we sensed already then that there was potential in combining our virtual and physical space in the location. Yet, at the time, we could not quite put our finger on its possible benefit. Summing up the thoughts gathered in my conversations, I can say that we have taken great steps in the data collection technology as big data, sensors and algorithmic processes have a particular impact on our physical environment. Then again, as architects, urban planners and other designers of living environments, we are still in the early phase of making the physical spaces kinder to people by digital means. Similarly, we should not forget that technology is merely a tool. Designing living environments continues to be based on values, whether they include streamlining, human scale, sustainability or smartness.

YOKO ALENDER is an architect and politician, a member of the current composition of the Estonian Parliament and the vice-chair of the Environment Committee. She contributed to the Estonian exposition Joint Space at the X Venice Architecture Biennale in 2006. Her special interest is the interaction between space and society.

HEADER: The website jointspace.ee established for the Estonian exposition at Venice Architecture Biennale in 2006. The environment featured the real-time location of its members, allowed forming groups, leaving comments on (urban) space, etc.

PUBLISHED: Maja 103 (winter 2021) with main topic Smart Living Environment

1 https://wiredelta.com/how-was-facebook-developed/

2 Public Information Act (RT I 2000, 92, 597) https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/115032019011?leiaKehtiv

3 Regulation (EU) 2018/1807 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 November 2018 on a framework for the free flow of non-personal data in the European Union (Euroopa Liidu Teataja L 303/59, 28.11.2018, 59–68), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R1807

4 Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information (Euroopa Liidu Teataja L 172/56, 26.06.2019, 56-83), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1561563110433&uri=CELEX:32019L1024

5 Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases (consolidated text), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A01996L0009-20190606

6 Bogdanov, Siil, Juridica 6/2020

7 https://sharemind.cyber.ee/satellite-collision-security/

8 https://www.sciencealert.com/iq-scores-falling-in-worrying-reversal-20th-century-intelligence-boom-flynn-effect-intelligence