Building materials do not come from shops, warehouses or retailers. Building materials are extracted, cut, processed, valorised, marketed, shipped from one end of the Earth to the other, back and forth, several times. Once the architect comes into play, the building material is already at the end of its production chain. The design developed in the architect’s head or on his desk is already a substance extracted from the Earth, ready to be transformed into concrete aggregate or a roofing sheet’s finish.

Giving and taking

Mark Wigley has aptly noted that architecture is usually considered the art of giving—a gift. We are used to the idea that the architect’s mind intertwines various elements in a way that the created whole results in added value, comfort, even abundance, pleasure, dignity, memories, and identity. Architects come across such vocabulary in school assignments and briefs. However, little is said about architecture being primarily the art of taking. In his essay ‘Returning the Gift. Running Architecture in Reverse’, Wigley says, ‘Seemingly static buildings are actually pieces of mining equipment, actively devouring the planet’.1 The text ends with a photo of Le Corbusier holding a freshly sharpened pencil between his crooked fingers that is about to touch a drawing in front of him. But what has to be taken from landscapes to turn that line into physical space?

The construction sector uses 50% of the globally mined mineral resources2 and mining has more than doubled in the past thirty years.3 Urban sprawl and urbanisation have a role to play here, accompanied by infrastructure reconstruction, new-builds in developing countries, reconstructions of existing buildings and the overall growth of comfort and population. The increasing need for raw materials has also activated mining in Estonia. One cannot build without opening new gravel, sand and limestone quarries. If we want to maintain or improve the current living standards, we need to make use of natural resources, including mineral resources.4

By extracting natural resources, they are separated from their natural state for human consumption. The concept of extractivism primarily refers to areas where raw materials come from: sand pits, limestone quarries, woodlands or clear cut areas. However, the plots where the raw materials are taken from are not sufficient to describe the wider impact of human activity on a global scale. Thus, extractivism could be considered as the art of taking, including not only the extraction of raw materials but also various other spaces, objects, relations and species with a considerable role played by large-scale landscape transformations and their long-term restorations, the infrastructure necessary for industry and its afterlife, transportation by land, sea and air, emissions from the waste and the machinery as well as the changes in the quality of biodiversity and people’s living environment. Extractivism is distinguished from mere mining by the dominance of human activity over other species and the treatment of the living environment as money, with its most efficient use constituting the fundamental principle of the currently prevailing economic system.5 According to Estonian literary and cultural critic Hasso Krull, it could also be called robbery.6

Hogging th resources

Anthropologist Francisco Martinez is studying the industrial ruins in Ida-Viru County in both spatial and symbolic terms. For instance, the former oil shale mine ventilation shafts suddenly collapsed, leaving hazardous four-metre-deep holes in the middle of the fields in Ubja. The given voids could be considered as the landscape negatives of the positive gifts described by Wigley. A post-extractivist landscape does not mean just closing the mines. Its impact will continue as a spatial void underground, an oversized infrastructure above the ground and a vacuum in the work and living conditions as well as future prospects of the locals. As to the afterlife of mining, it is not enough to physically fill the hole, it also requires the organisation and conceptualisation of the social afterlife.7

Natural resources have been harnessed for the well-being of mankind ever since the European centres expanded into global empires and the industrial revolution in 18th-19th century. Architecture historian Barnabas Calder opens his book Architecture: from prehistory to climate emergency with an aptly simple but critical and ironic line, ‘This book tells the story of how fossil fuels made the world a much better place for humans’.8 He analyses the canons of architecture history (such as pyramids in Egypt) as well as lesser-known buildings (such as shopping centres in China) through the energy sources available during their construction. In particular, he explores the application of coal during the British and American Industrial Revolution when construction, the extraction of raw materials and the production of building materials grew at an unprecedented rate with an impact also on the architectural styles and building techniques around the world. Calder’s statement is straightforward: architecture requires energy, the origin of energy in agriculture, coal or oil is related to the political power of the area and, if necessary, also the conquest of new areas.

History is brimmed with resource hogging. The research of French economist Thomas Piketty is devoted to global inequality where extractivism plays a key role. The development of Western industrial capitalism is closely linked to the international division of labour, the unrestrained exploitation of natural resources, and the military and colonial domination that developed gradually between the European powers and the rest of the planet and accelerated during the 18th and 19th centuries. By the end of the 18th century, Europe had spent nearly all its available forest resources (decreasing from around 40% of the surface area in 1500 to scarcely more than 10% in 1800). The European constraints were overcome by the ‘discovery’ of America, trade with Africa and Asia. It would be naive to imagine that the effects of colonial heritage are surpassed. Quite the contrary, history requires collective responsibility and discourse in order to change the world economic systems and the legacy relying on injustices.9

It is therefore necessary to specify the concept of extractivism with another feature describing the instrumentalisation of natural resources for the benefit of the selected few. Even as fossil fuels, petrochemicals and technology have provided people with unprecedented comfort, the colonial legacy continues to define the ownership of natural resources, the ethics of extractive processes and reparations, unpaid labour and the quality of conditions, social inequality and modern slavery.

Extractivism describes economic dominance. If extraction is an activity, then extractivism is an ideology relying on a model of taking without giving anything back, regardless of externalities, and targeting all resources to the well-being and profit of people or, to be exact, selected people. Thus, extractivism is not characteristic of capitalism only. The legacy of the mining and biochemical industries in Ida-Viru County grotesquely represents both the communist and capitalist model based on extractivism. Martinez has found that since the infrastructure of the power stations in Ida-Viru is now underutilised, both Estonian and foreign companies have brought energy-intensive crypto-mines to the region. A new kind of mining and also a new kind of pollution and colonialism will replace the old one. But the money doesn’t stay in Ida-Viru County.10

Tracing material circulation

Coming back to building materials, for instance, high-quality sand needed for construction is a globally scarce commodity that, in addition to the destruction of natural habitats, is considerably affected by illegal mines, sand mafias, inconsistencies in laws between countries, and according to the UN in desperate need of international monitoring.11 The list of critical raw materials imported by the EU and also Estonia mainly consists of metal ores, including aluminium exported by China and copper provided by Russia and Ukraine. Basically, you can buy tons of metal ore from the Chinese online store Alibaba, with no description of its social price. While the EU standards at least attempt to keep the carbon footprint under control, the materials from outside the Union that are inevitably used by various manufacturers of building materials and components may circle around the world several times with their origin apparently deliberately obscured and thus untraceable. It seems highly paradoxical to discuss the sustainability of welfare states and climate crisis mitigation when the global material circulation is not monitored.

Steps have been taken towards building material lifecycle assessment: for instance, there is the Life Cycle Analysis method (LCA) for buildings used for the quantitative measurement of a building’s carbon footprint starting from the raw material extraction to demolition and possible reuse. Anni Oviir, an expert on the lifecycle of materials and one of the authors of the Estonian vision ‘Construction Roadmap 2040’ says that although it is carbon tunnel vision, it is the best we have as it can be applied immediately. Material circulation (from demolition contractors, logistics, certification of building materials for construction up to digital material banks) is developing rapidly and with it also the understanding that there are many factors that cannot be described in numbers only.12 The given tunnel vision emphasises the reduction of only one technical carbon emission number while ignoring the intertwined complexity including education, health, social inequality, overconsumption, nature conservation etc that above all could affect general awareness and behavioural patterns than mitigate the problems of the climate crisis with a hidden technological improvement.13 Oviir is critical of architecture that, like fast fashion, tends to follow seasonal trends. We see also in Tallinn how buildings in good condition built 30 years ago are demolished for filling land or how office building façades do not last even 10 years and come to be re-dressed in metal, aluminium and glass suits and dresses. How to plan flexibility for a building at least for a time period in which the embodied and operational carbon could offset its construction in terms of carbon footprint? And this is only a technical aspect. What kind of a building is sustainable for our way of life, spirit and sense of beauty that we would be prepared to care for over several generations?

Drafting the future spaces

From the perspective of limited resources, architecture will be faced with several challenges that are directly related to the origin of raw materials. Among other things, it is important:

- to search for, certify and use building materials from currently empty or condemned buildings (urban mining);

- to design buildings from ecological and biogenic materials with as small carbon footprint as possible;

- to use natural materials in line with sustainable agricultural and forestry practices;

- to design structural connections so that they could be easily disassembled (design for disassembly);

- to improve the efficiency of load-bearing structures to decrease the volume of energy-intensive steel and concrete.

The house with the best environmental impact is still the unbuilt house. Not constructing should be the absolute starting point for every client in order to analyse their actual needs. Formalising such a brief requires further effort also in legislation, local governments and heritage conservation in order to find new functions for abandoned buildings, arrange competitions for their renovation and extension or even value the preservation of Soviet modernism that tends to suffer from cultural burdens rather than spatial deficiencies. Aesthetics is not unimportant either, as it is the task of architects as creators of space to experiment with the threshold of beauty within the profession and among the general public.

And then the most important ethical question for architecture—for whom and why are buildings constructed in the first place? According to Jevons paradox, every step towards a more efficient use of a resource tends to lead to the increase rather than decrease of its use. If we find a way for the most efficient use of resources, is it an argument for further building? Is a skyscraper with luxury apartments made only out of reed a sustainable building? In order to avoid the dominance of the above-mentioned selected few over their own and other species, resources must be led toward an equal society or otherwise we will halt the climate crisis mitigation and undermine social sustainability. This is what we are currently witnessing.

Nature and natural resources shape the self-image of a nation, state and culture and determine international relations on every level: political, economic and military. As a society, we are the heirs to this treasure and as a state, we have made a pact to use it sustainably and prudently.14 The responsibility of the architect in this should not be underestimated as construction is directly related to the transformation of the material taken from the ground according to the design drawn by the architect. Until spatial design does not take the origin and social cost of the materials seriously, we will continue to plan mines that we may not be aware of or turn a blind eye to.

ROLAND REEMAA is an architect and a lecturer, a founder of LLRRLLRR studio. In 2023, he is the recipient of the Cultural Endowment’s “Ela ja sära” grant.

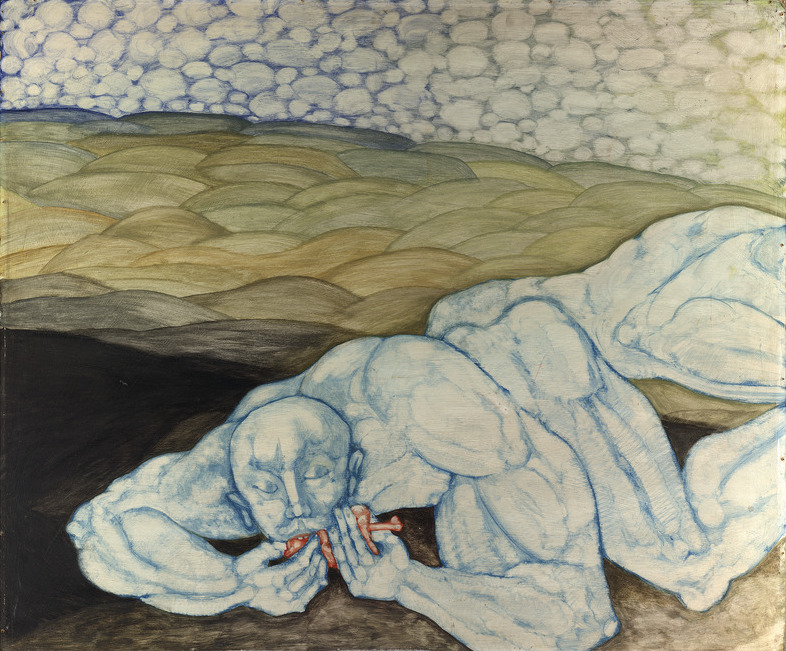

HEADER: Rein Tammik’s painting ‘Gluttons II’ from 1970.

PUBLISHED: Maja 112 (spring 2023), with main topic Moratorium

1 Mark Wigley, „Returning the Gift. Running Architecture in Reverse“, Non-Extractive Architecture: On Design without Depletion, peatoimetaja Space Caviar (Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2021), 47.

2 European Commission website ‘Buildings and construction’

3 Felix Heisel, „Reuse and Recycling: Materializing a Circular Construction“, The Materials Book, peatoimetajad Ilka Ruby, Andreas Ruby (Ruby Press: Berlin, 2020), 156.

4 ‘Maavarad’, a website of the Ministry of Environment.

5 Kadri Tüür, ‘Vaba mõtlemine, keeruline lugemine’, Keel ja kirjandus 4 (2021): 334.

6 Hasso Krull, ‘Imelihtne tulevik. Kaheksa kannaga manifest’, Sirp, 11.05.2018.

7 Roland Reemaa’s interview with Francisco Martínez, 3.05.2023.

8 Barnabas Calder, Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency (UK: Pelican, 2021), xi.

9 Thomas Piketty, A Brief History of Equality, translate into English by Steven Rendall (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022), 48–55.

10 Francisco Martínez, ‘Allakäik, kestvus ja ülbusevastasus. Interview 5.10.2021’, Ehituskunst 61-62 (2022), 97.

11 Sand and Sustainability: 10 strategic recommendations to avert a crisis, United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP/GRID-Geneva (Geneva, Switzerland, 2022).

12 Roland Reemaa’s interview with Anni Oviir, 5.05.2023.

13 Ploy Achakulwisut, Patricio Calles, Almeida Elisa Arond, ‘It’s time to move beyond “carbon tunnel vision” ‘, SEI blogi Perspective, 28.03.2022.

14 ‘Maavarad’, a website of the Ministry of Environment.