The FinEst Twins Smart City Centre of Excellence aims to establish a platform for Estonian smart cities to match Estonia’s high-level presence as a digital state. What are the challenges that Estonian municipalities must face when creating a smart living environment?

What is a smart city and a smart built environment?

The development and application of smart city solutions are increasingly seen as an effective and sustainable way to handle various urban challenges such as growing urbanisation and urban sprawl, increasing and decreasing populations and the capacity of a city to, e.g., despite diminishing resources, provide a high-quality living environment and services to its residents while aiming to reach goals set in a wide range of agreements in environmental, international and other contexts.

The Smart City Centre of Excellence (CoE), which opened in December 2019 as a designated institute of Tallinn University of Technology and which is jointly financed by the Horizon 2020 FinEst Twins project and the Estonian government, is led by a vision to deliver a smart city platform from state level to local governments across Estonia. The broader perspective of the CoE is to establish itself as a trusted Smart City competency centre at a global scale.

The majority of Estonian cities are very small even in the European context and most of them could benefit from smart solutions that help them to tackle the problem of diminishing resources that come with declining population and other challenges brought about by, e.g., urban sprawl. The services for the residents are centralised in county and city centres and enabling service access for rural inhabitants has proven to be a considerable challenge. Smart approaches in the transport service sector such as demand-based transportation solutions and enabling micro-mobility solutions such as electric bikes could be a huge relief. In short, Estonia needs an R&D approach toward a smart built environment.

In order to test smart city solutions outside the capital region, the Smart City CoE will implement up to ten smart city pilot projects between 2021 and 2027 in different Estonian cities and local municipalities, all stemming from challenges characteristic to that particular region.

An important part of the FinEst Twins project is collaboration with Finland, especially with the innovation unit Forum Virium Helsinki of the City of Helsinki and Aalto University who as cofounders of the Smart City CoE, alongside Tallinn University of Technology and the Estonian Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications, have considerable experience in testing innovative solutions in urban environments.

The smart city as a term is used in many different fields and is tightly conjoined with changes that occur in society on the one hand and in technological advancement on the other, which is why it is difficult to point out a singular definition for what a smart city is. When the term was introduced in 2007, ‘smart city’ was being defined primarily as a joint space for humanitarian values, social capital and IT infrastructures, that would enable sustainable economic growth and rising quality of life. In Estonian, the term ‘intelligent city’ was taken into use although ‘smart city’ may have been a better fit (using the same logic as with ‘smart phones’). Over time, the focus of the smart city has changed—whereas up to 2010 most of the attention was on new and innovative technologies, i.e., the tools necessary for creating a smart city, the last decade has been increasingly involved with what these technologies are trying to achieve. An understanding has been reached that no city is made smarter by the mere use of technology; a city becomes smart when the technology is employed in a way that people’s living environment improves, governance is made more transparent and inclusive, and transportation becomes less polluting and commensurate to the actual needs of the citizens. While technology maintains its pivotal role in the development of a smart city, an equal, ethical contender—the citizen’s right for privacy—has emerged by its side. A realisation has also come forth that if the conditions of user-friendliness and focus on actual problems are not met, the solution will not have use, no matter how innovative and technologically savvy its nature.

The current concept of a smart city entails a primarily anthropocentric view and is based on tight cooperation between the inhabitants, the private sector, the state sector and educational institutions (e.g., universities and different institutes). While the technocentric approach to a smart city viewed inhabitants as dehumanised sensors or objects reduced to data points whose purpose is to service strategic development, the modern approach is increasingly inclusive of humans as active participants in the inception and governance of these systems. There has been a realisation that active cocreation can potentially yield results that have a far more positive impact on the community as a whole and enable broader implementation and acceptance of novel solutions.

In conclusion, we may say that the primary purpose of a smart city is to find innovative means to acute urban challenges via technology. The European Commission’s definition of what a smart city is has become much broader compared to previous times, encompassing requirements to tackle climate goals and, also, the smart city approach is seen as an opportunity to provide innovative solutions to the challenges deriving from overpopulation, ageing society, and growing urbanisation. The smart city is hence a place where various information and communication technology solutions have become integrated to ensure a more effective use of our resources and lower emissions, while simultaneously meeting the needs of the inhabitants and raising their quality of life. This concerns many of the urban domains, such as governance and services to the residents, transportation, energy, circular economy, healthcare, urban planning, etc.

Can Estonian cities be considered intelligent and smart?

Last summer, the FinEst Smart City CoE asked 36 Estonian cities and municipalities five questions concerning the challenges around the smart city concept. For example, one of the prompted themes was to pinpoint the most acute problems that the cities must solve within the next 5 to 10 years in the following domains: data, governance, energy, mobility and transport, the built environment and urban planning. The cities were also asked to give an overview of smart digital solutions that they might have in use by the years 2025 and 2035. The smart city concept was not defined by the questions to allow some space for free interpretation. This nuance gave us the chance to examine how the respondents conceptualise the smart city for themselves and the problems that their interpretation might create or solve.

Estonian local governments are rather well informed of the smart city concept and they show great interest in actively contributing to the ensuing projects and their advancement. At the same time, the responses to the survey and the following interviews were largely dependent on who the responding person was. In general, it was either a development manager or a specialist giving the feedback but in the cases of Sillamäe, Võru and Haapsalu, the mayors contributed to the exchange as well.

Larger cities such as Tallinn and Tartu have already undergone many different smart city focused projects. For example, Tartu contributed to smart transportation by employing CNG buses, performing a busline efficiency analysis that combined various data sets (including mobile phone data), and combining public transportation with a network of electric bikes. In Tallinn, smart traffic lights have been implemented at 45 traffic junctions which make for a faster and more efficient public transportation system since the traffic lights give right of way to public transport vehicles. Collaboration with Taltech also saw to the completion of the smart pavement project (2015–2018) which introduced Tallinn as the first EU capital to have the opportunity to install smart pavements, replacing asphalt paving and traditional pavement stones. The e-pavement features solar power generation and storage options integrated with snow and ice removal, slip sensors, motion detectors and other sensors supporting management of the transportation system as well as need-based illumination options for roads and objects. Various electronic components can be integrated with e-pavement. A spin-off company of Taltech has begun manufacturing the pavement so that our future roads would be communicative with its commuters, and vice versa.

Many smaller local governments have shown good initiative as well. For example, an app to improve the transparency of the government and communication with the citizens has been developed in Hiiumaa and Elva. Lääne-Harju Parish has a functional community committee whose purpose is to aid in the information exchange process between the parish and the population, and in its social and economic development. The City of Keila is interested in hosting pilot projects on developing and implementing hydrogen technology. Preliminary judgments indicate that transferring urban and county level transport solutions from the current technology (diesel, gas, electricity) to a hydrogen platform seems a realistic and economically promising solution on both highways and railroads, and the City of Keila, for example, would like to test hydrogen trains on the Tallinn-Keila railroad segment.

The City of Pärnu wanted to test hydrogen technology options in public transportation a few years ago, but the technology was still in its infancy back then and maintenance costs for the buses would have been through the roof. Pärnu then decided to implement a 100% biogas policy on all of its buses. Both Tartu and Pärnu use solely sustainable energy sources in their public transportation systems—all city lines run on biogas and electric city-bikes on green energy. Tartu has struck an additional deal with the Alexela company to cover the lighting of the city, its institutions, kindergartens and schools, and will have become a city illuminated fully by green energy by 2021. Street lighting will be 100% LED.

Despite these efforts, we don’t see Estonian cities in the front rows of the smart city race. For example, according to the Smart Cities Index 2019 and the IMD-SUTD Smart City Index Report 2020, Tallinn holds the 74th and 59th position, respectively. At the same time, our northern neighbours, the cities of Helsinki, Stockholm and Oslo have had considerable success in developing the smart city concept and normally feature at the top of the lists drawn to evaluate smart city progress.

Cities as lonely islands in the digital state?

Only a few Estonian cities have managed to aspire towards smart city goals for different reasons. The majority of Estonian cities are very small in the global context and in addition they must also face challenges connected to ongoing diminution. For finding additional funding needed to develop and test innovative urban solutions, the cities are lacking financial resources as well as human resources and skilled specialists. Diminishing towns have to deal with tense budgetary restrictions and in situations where inhabitants cannot be guaranteed the most elementary services (such as quality public transportation fitting the needs of the residents to ensure access to important services such as medical aid, schools, kindergartens, workplaces, etc.), it is difficult to justify expenditures to develop innovative technologies whose final results and actual benefits are unknown and are in a need of monitoring and assessment. Although the survey produced only a few answers that claimed lack of financing as a problem, and the general trend in attitude was that limited funding will not be a significant obstacle, the inevitable reality is that without a designated city official specialising in smart city development, political backing and a shared set goal to move towards establishment of a smart city, it is difficult to find motivation and time to seek additional funding for smart city development.

Attention was drawn to lack of sufficient state level support and guidelines, which is why cities facing these problems have each taken individual paths toward developing these smart solutions. In other words, instead of putting in shared effort (e.g., joint innovation procurements) to achieve better solutions that would run on similar standards for data storage, for example, and would therefore be interoperable, comparable and of similar logical framework for the end user, the Estonian digital state is seeing the appearance of so-called digital islands in each local municipality that are unable to relate to one another or communicate amongst themselves.

To break this fragmentation and unevenness, it is important to create tools and standards at state-level to enable implementation of the best developed practices for local governments who have not had the chance to hire a competent specialist to do the job.

Challenges of Estonian local governments

In the summer of 2020, the Smart City CoE received responses from 16 cities and local governments to a survey designed to map their most pressing challenges. Subsequent interviews were carried out to get more detailed information about the survey. Based on the feedback we concentrated 19 challenges which we then asked 36 cities and municipalities to evaluate on a 0–3 scale. Based on the feedback we received to that query, we compiled a ranking of the most important problems faced by the municipalities which we confabbed with the respondents at a subsequent consensus meeting. We then introduced a few changes and found out what the 10 most important and pressing concerns are to which Estonian municipalities would like to find a smart solution.

The top 10 challenges in the fields of energy, data, governance, mobility and transportation, the built environment and urban planning, are (by order of importance):

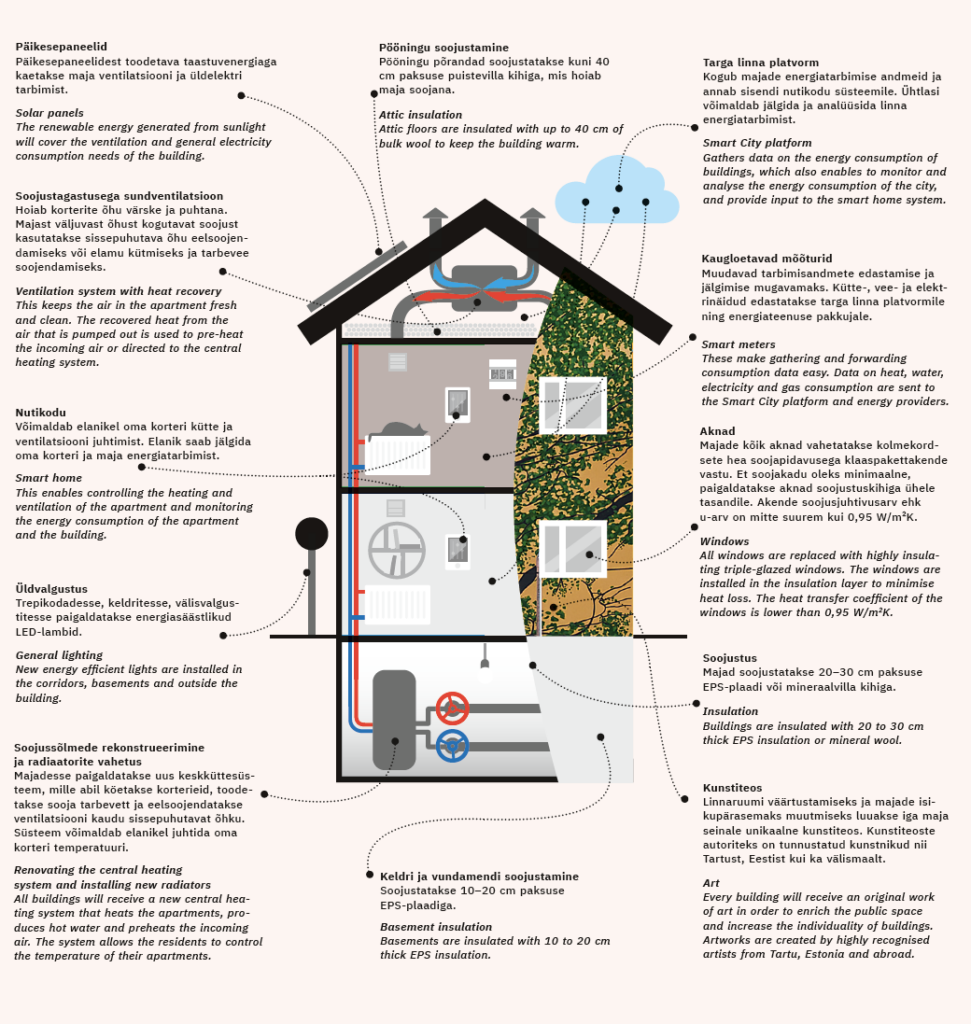

- Energy consumption of (depreciated) buildings is too high—Energy.

- Urban Mobility does not combine the full potential of different modes of transport—Mobility and Data.

- Energy supply and transport infrastructure for industrial development is low—Energy and Built Environment.

- Insufficient and/or uncomfortable public transport—Mobility, Data.

- Lack of fast and economical connections to other key cities—Mobility.

- Data to be collected is not available to different user groups—Governance and Data.

- Skills and capacity to collect and use data are low—Governance and Data.

- Public services are not accessible to all target groups—Governance.

- Energy production is too carbon-intensive—Energy.

- Urban planning is not comprehensive, optimal and sustainable—Built Environment.

Does testing new technologies in the city enable smart city development?

By today, collaboration toward the smart city platform has become very practical. The ambition of the FinEst Twins Smart City CoE is to raise the smartness of Estonian cities to the same level as the current Estonian digital state by executing the pilot projects during the next 4–6 years. The European Regional Development Fund and the Republic of Estonia have contributed to the funding to implement the pilot projects.

The process of raising the smart competency of Estonian cities and municipalities was initiated by the City Challenge idea competition for smart city pilots which deadline was November 6th, 2020. The idea competition searched for concrete ideas, practical scientific solutions with which to make different Estonian cities of varying size and location more human-friendly, economical and create a better living environment. A significant factor in the evaluation of the ideas was their potential for scientific inquiry and sustainability. Preferred solutions enabled panning out across other cities of similar type in Estonia, Europe, and globally.

71 competition entries were filed by the competition deadline and the winners were selected at the end of December. An international jury selected four pilot projects for testing, two of which were from the energy category. One of the pilot projects to be implemented in Tallinn and Tartu will introduce to local governments a digital tool that provides systematic overview of the energy efficiency of buildings. Another pilot project in the energy category (applied in Tartu, Paldiski and Lääne-Harju Parish) provides municipalities means to solve their energy supply problems, whilst also increasing the uptake of carbon-neutral energy, through the use of energy storage systems and electrical microgrids. During the project, research is carried out focusing on energy storage systems, cyber-security in electricity grids, energy policy and markets. The category of mobility and urban transport produced a winning concept of user-centric transport system management, which focus is on creating a data exchange platform called ‘X-Road’ based on the notion of mobility as a service. The goal is to use demand-based transportation to improve the connectedness between the heart of Tallinn and its vicinity. In the category of the built environment and urban planning, the pilot project ‘Green Twins’ was selected winner. The project will introduce an easy-to-use digital plant-model resource ‘library’ to facilitate spatial design in 3D urban models. The library will be comprised of the digital twins of plants found in Tallinn and Helsinki.

The beginning of 2021 will already start to see realisation of the ideas. The next smart City Challenge idea competition for pilot projects welcoming smart solutions to tackle various urban challenges in collaboration with cities and local municipalities will be announced in the coming spring.

The FinEst project has received funding from the H2020 programme (grant no. 856602) and the Estonian Ministry of Education and Science.

LILL SARV holds a doctoral degree in semiotics and acts as researcher and Head of Project Development at the FinEst Twins Smart City Centre of Excellence.

HENRY PATZIG acts as Deliverable Manager at the FinEst Twins Smart City Centre of Excellence.

Article is published in Maja’s winter 2021 edition Smart Living Environment (103)

Header: the self-driving vehicle Iseauto was completed for the 100th anniversary of TalTech in cooperation with Silberauto and other partners. There was such great interest in the vehicle following its launch in 2018 that the company Auve Tech was established for its production on the basis of Silberauto development department. Foto by Auve Tech.

1 Francesco Russo, Corrado Rindone, Paola Panuccio, „The process of smart city definition at an EU level“. Sustainable City 2014, vol 191 (2014): 979–989, DOI: 10.2495/SC140832