I sat down with Judith Lösing, Julian Lewis and Dann Jessen, the three directors of East Architecture Landscape Urban Design Ltd., the architecture office I work with in London. As an office it is not uncommon for us to exchange ideas and discuss matters that might not have a direct connection to a project but that are a part of a wider architectural discussion. For this issue, I invited the three directors to discuss the way East’s practice that spans around 20 years relates to the theme of authorship in architecture and how practicing more or less exclusively in London shapes that relationship.

As conditions in London are often pushed to their extremes, the city becomes relevant as a case study for architectural matters internationally. It is under several pressures, the biggest of which must be that of money and the flow of people, which in turn and as reaction pave the way to a proactive public sector and planning system. My intention was to discuss the part that London plays in the way architects operate here, what sort of practices are born from it and the work that East has done in response to this condition.

Laura Linsi: From my own experience of working with East, I have an understanding of how authorship is ambiguous within East’s practice but also how it is characteristic to practicing in London in general. I’d like you to shortly describe what you think of as being specific to practicing within the London condition.

Dann Jessen: London is just one place, just one city, so physically it is small. But in terms of density and uses and money, it is enormous. It is enormous enough for a lot of people to work as architects in London without spreading to other cities or countries. There is something quite extraordinary about working so locally – there is an everyday aspect to it. It is not surprising to come across a space you have worked on a couple of years back, they are all around the corner. This feeling of working into the everyday has brought people and the city, the situation really, into the foreground. That can only be the case because we live in a very particular condition where the space is small, but intensity is high.

Judith Lösing: The planning process in London is different from any other European city that I know. In other cities, there is a masterplan which gives you very strict guidelines to work to but then within these guidelines you would also know what your freedoms are. Whereas here, every single project is a complete negotiation from beginning to end, nothing can be taken for granted. Every project is generating itself.

Julian Lewis: A traditional masterplan process sequentially leads to a built development, to newness. It’s like saying there’s a new piece of city coming. But in London, the understanding is that the city is already there so you need to join in with what already exists. The paradox is that no one knows what it is. So with each project you’ve got to try and understand it. We do it by making drawings and models and by talking about it. We are reading into it in a negotiated way. This results in a different sort of design.

Laura Linsi: How is that different from designing into other cities’ existing conditions?

Julian Lewis: It has to do with the nature of negotiation in London which is more charged and often more affected by complex governance than many other cities at the moment when a masterplan brief is drawn up. The client is often a group made up of a variety of officers, statutory bodies, and community representatives with conflicting or emerging interests. You’re already starting with something that’s compromised, unclear, might never happen, might happen in bits. All of that unclarity and immense amount of time it takes, complications that come with it – they undermine the clarity about the newness one might expect in some other European cities where you make a masterplan, develop the designs thereafter and build it two years later. We have to engage positively with this complex situation and work with it architecturally.

- The photos shown here by Jason Orton were not commissioned by East. Indeed Jason was unaware that these places he photographed were designed at all, let alone designed by East. Yet they capture accurately the atmosphere and spatial character we sought to achieve through designing into this left over landscape in a way that acknowledged that landscape. The river edge at Rainham is a powerful space to experience, and walking next to the corten steel and concrete retaining wall, one is made aware of the expanse of the wild river and the beautiful void created by roads and large inaccessible warehouses inland. East’s designs comprise a series of infrastructural adjustments using paths, stairs, ramps, seats and aprons of concrete, spliced into the existing landscape. These engage with the river, the marshes, the roads and the warehouses to allow the visitor to be in that landscape rather than observe it from a position of an outsider.

Laura Linsi: That makes me wonder, do you think important ideas can get lost within the process? Do projects in London tend to end up flat and even?

Julian Lewis: Ideas are really important because otherwise everyone is just lost at sea. It is a fascinating process to have everyone negotiating to make a project happen. At some point you realise, people don’t know why they are negotiating other than to get the planning permission. That means there is a hollow core to the actual reason behind the process.

And so to answer your question, we find ourselves forced to ask ourselves where we get satisfaction from and where we place value. We realise, we do it unevenly. Rather than everything being homogeneously important, we sometimes specifically let some things go and place a fix on others.

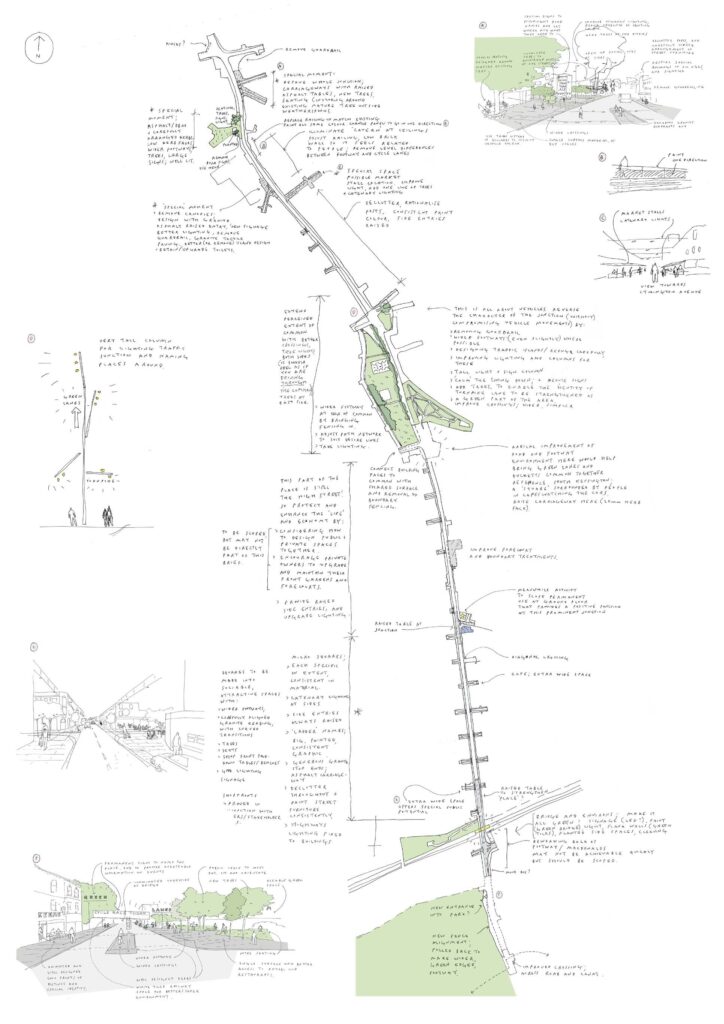

- This 3 km project involved an extraordinary diversity of stakeholders, client groups, funding sources, community advocates and project proposals. Communicating with these groups through to delivery took several years. But the process was not always carried out slowly. This drawing, arranged as it was drawn, was an early attempt to capture the whole proposition for the street in one go. We call this kind of drawing a hairy drawing; where thoughts and ideas are drawn and written at one sitting until they run out. The drawing, rapidly made, was aimed at identifying a full, though inevitably provisional, range of proposals and their relationships. The drawing is part of the method of capturing ideas, and also a tool for communicating them to ourselves as well as others.

Laura Linsi: Ambiguity in authorship seems to be built into the process you’ve just described.

Julian Lewis: Working together is inevitable, because London is complex – there are so many different groups of people that you have to collaborate on ideas, you have to think together. And within this complexity, someone needs to speak about the place and understand it, and think how to extend it.

Dann Jessen: What do we actually mean by authorship? Do we mean self-obsessed authorship of getting one’s name hammered into a stone plate for it to be remembered for another hundred years? Because I personally couldn’t be less bothered. There is an expectation about authorship – that taking an idea and carrying it through from strategy to detail, this is what one does. There are projects, therefore, which are perfectly legible and you know who authored them and so on.

Judith Lösing: That’s almost a bit vulgar.

Dann Jessen: And somehow a little bit distasteful.

Julian Lewis: Impertinent.

Laura Linsi: So what’s a different way of operating?

Dann Jessen: It seems to me that for the last 20 years or so, there’s been a specific desire to try and work to an extent without authorship in the city. There’s a desire to acknowledge that the existing situation is already a piece of design and you might do very little to adjust it, improve it, rather than to redesign it. As soon as you start thinking how you work into existing situations and improve them, you are creating a different cultural context for the architectural project.

Julian Lewis: If you design with a signature you tend to pull things toward you and if you tend to avoid designing with a signature and instead bring rigorous interest into looking outwards to the city, you feel more satisfied about the good relationships with what’s around. Signatures tend to be personal, and are therefore less interesting.

- East took an urban perspective in shaping this project; the architectural judgments were informed by, and made good relationships with, the local context at each side. We used three materials: brick, precast concrete and aluminium. We rejected ‘detailing’ or embellishing the facade, preferring to place all our efforts on making careful judgements on proportions and arrangements of these materials. The concrete base sets a datum for the brick conglomerate envelope above; a continuous, shaped surface that defines a single urban volume containing multiple uses. Windows are large, and larger still on the top two floors. The eastern façade sits opposite the park and pulls back for a wider footway; the bricks on this face are rendered with matching mortar. Elsewhere, more loosely arranged façades respond to yards and side streets. The entrance canopy, roof shelter and pavilion provide a second scale of thresholds, invitations to be close to the building.

Laura Linsi: Can you think of authorship without explicit signatures attached?

Judith Lösing: You can also see authorship as something more positive – such as getting an idea built as it was conceived rather than having it watered down by millions of compromises and design workshops where every single box needs to be ticked. That is authorship that is more about the clarity of ideas.

Dann Jessen: What makes London special though is that you can’t actually implement a single idea. That nullifies the whole discussion about authorship. Suddenly you’re free to think about the place itself. Authorship is transferred to a situation, it becomes a place and you can engage with that deeply. The whole palaver of a traditional trajectory and culture of architecture is set aside. That is what’s most amazing and refreshing about London – the notion of authorship and singular idea is set aside. It can be bloody irritating but it is also amazing.

Laura Linsi: How does that relate to East’s own projects?

Judith Lösing: We had a discussion in the office the other day about quality and which projects we like and enjoy the most. We were saying that there is rigour in our landscape projects that is not quite matched in our buildings yet. With a landscape project, the client is the place. We can determine the brief, we can be very site specific.

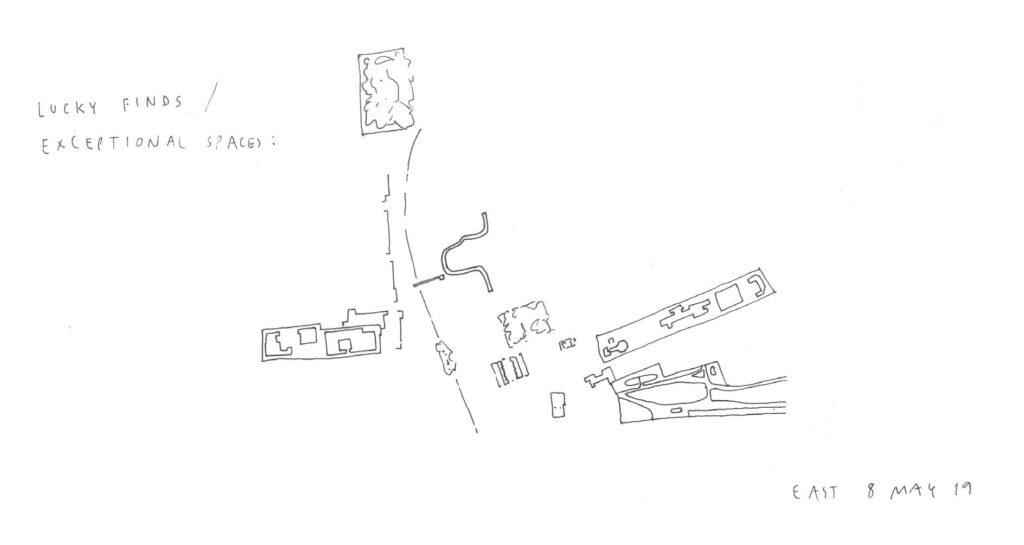

Julian Lewis: Public realm projects are naturally outward spreading. With our students, we’ve been looking at big sheds, barbed wire fences, reservoirs, rivers, as if they’re a magical city. We have desperately wanted our students to draw them with care, which might seem like a strange thing to do, because all of these seem to be irrelevant to most people. We love it because these diverse components are all parts of the condition of a place. By putting these pieces together, you describe a condition within which you might intervene in a very small way but have an impact across all scales. An adjustment to a path means you are suddenly taking ownership over all of the barbed wire, the reservoir and the sheds. As an architect you’re designing it even though it is not changing. You’re taking interest.

Laura Linsi: East’s work on high streets is particularly interesting in this context. London high streets span legal ownership boundaries, economic and social systems, plain logistics and infrastructure. They’re never singular and straightforward. It is an urban typology most characteristic to London – it really stitches the city together.

Julian Lewis: High streets are almost impossible for people to contemplate because they’re so long and stringy, varied, with lots of shops, and yet that’s their strength. They are very interesting for their radical diversity for all sorts of uses, forms and timings. I think we are good at that. We get that, we like that we can draw it, we can present it and we can make a strong story about something that isn’t singular. This is something that can be used to shape architecture.

Dann Jessen: What is really nice about them is that they are in some ways refurbishment projects. You have to give in – every little move is touching something existing. Nothing about the landscape or the public space is under control.

Laura Linsi: Is there a tactic, a strategy to East’s approach that these projects reveal?

Julian Lewis: Not being afraid to show differences and to look at things for what they are, not to think that’s a bit ugly and that’s quite nice. We are non-judgemental, very open to situations, allowing ourselves to explore some things that might otherwise be familiar. We can present it very strongly.

Dann Jessen: Surely in terms of our view of London, it has absolutely and totally been shaped by us not starting with house extensions and moving up the scale of buildings. We started with these incredibly strange projects, which were totally out of control. It was all about aligning existing spaces, doing that little bit over here that then validated a larger idea that you could otherwise never have the means to influence.

Julian Lewis: We do like to be straightforward. The idea of embellishing buildings to be architectural or the lack of ideas in embellishment – rather than embellished buildings per se – is disgusting, really. So we try to find a way of creating meaningful articulation and space, and placing emphasis on making good relationships between materials. Knowing how to describe something accurately, especially with drawings, is really important.

- The public space at Passey Place on Eltham High Street was already there, though congested and of poor quality. The new space, which traverses the road to deter car speeds and engage with the street side opposite, uses a new striped granite ground, mix of trees and granite seating marked with names of local people like the traditional memorial benches seen across the city. Though the Eltham High Street improvements generally provide a new good background, Passey Place is one of the more visible parts of the design, evincing Eltham’s rich historic identity evident in the nearby Art Deco Courtauld Institute, Eltham Palace and the Victorian arboretum at Well Hall Pleasaunce.

Laura Linsi: There seem to be a lot of requirements for the developers to offer play space, open space and other amenity back to the city as part of the new development. Public realm is now an integrated section of any planning application, it needs to be a part of the development strategy. Has it always been like that?

Dann Jessen: Public realm has become mainstream. Both in terms of being given value and attention but also as a method in which design and authorship are pulled back. It wasn’t always like that.

Julian Lewis: It really has become a prominent topic. This terminology didn’t even exist before. Nowadays, the most greedy inward looking developer will have to demonstrate their approach to public realm and public interest. They are asked to lead on that dialogue.

Laura Linsi: East is partially responsible for that happening, I suppose. Are there still ways to expand that discussion?

Julian Lewis: Recently I went to a review of a statutory programme of delivering public spaces across London. My role was to look at new design guidance coming forward. At one point, the managing team said that under so many millions of pounds they won’t worry too much about having a design review. We asked how many of that scale projects they have. It was lots. With no relationship between them, they are just like little fibres in the city, each delivered with nominal amounts of paving and maybe a tree. It occurred to me that individually they might seem unimportant, but together they can make a big effect. The obvious thing to do is to package these up together to create a big project. There is still a great deal of space for this kind of discussion to happen in London.

LAURA LINSI (1989) studied at the Estonian Academy of Arts, Rhode Island School of Design and at the Delft University of Technology. She works on art, exhibition and public projects as an architect and a teacher. In2016, together with Roland Reemaa she founded the practice RLOALUARNAD to study everyday complexities across the city and the countryside.

HEADER photo by Nik Klahre

PUBLISHED: Maja 98 (autumn 2019) with main topic Author