SPATIAL EXPERIMENTS OF PAIDE SQUARE

Architecrure: Elo Kiivet

Assistants 2019: Kalle Komissarov, Kadri Kallaste

Team: Maiko Keskküla (leader), Tiit Kanne ja Kaspar Tammist (project managers), Indrek Kuuse and Alver Tõlgu (builders), Kristjan Kirsipuu, Jaan Kirsipuu (assistants), Ülle Müller, Kersti Viilur (cultural program managers)

Commissioned by: The Opinion Festival, Paide City Government

Area of the experiment: 3300m2

Open to the public:

15.07.–12.08.2017

30.06.–20.08.2018

29.06.–20.08.2019

For three consecutive summers Paide central square has provided a collaborative platform for locals, participants of the Opinion Festival and municipality to find the best possible joint space for the community.

A space unknown and distant often appears to us in black and white, simplified to a fault. In a state where a third of the population lives in the capital, it is the small towns that inherit this role. They are established as depressive by one, or too insignificant to see elementary services maintained by another. The idyllicism of small town farmers petting their sheep and remote work culture nomads in action is an equally suspicious scenario, reversed. Stereotypical thought does not identify midtones, resulting in loss of ties with real life, often clouding the inner life of small towns. You can only witness the variegation and warmth whilst there in person.

Black. Depressive Small Towns of Estonia

The recently completed study on small settlements states that migration is one of the most significant processes directing the evolution of a population: yet the degree of polarisation along the regional centre-periphery axis that we see today has not been encountered in the Estonian habitation system thus far. Migration towards centres has been intensive in the last decades, flow in the opposite direction, on the contrary, remains modest.i Adding the collapse of collective and state farms that followed the reinstatement of independence, the diminishing demand for human labour in agriculture in light of technological advancement, the convergence of higher education and services, and mixing all that with a diminishing and aging populace, we get a rather dim view of the status and outlook of a small town.

But, why should we compare a small town to a large one, the perpetual making of haste, mass consumption and the so-called average human? How appropriate is it to speak of depressiveness in a place where the brightest individuals do not stand out because they are not posing over national media, but are instead focused on developing local (cultural) life with impressive vigor? Why must one daydream about far-away franchises arriving one day, or wait for the city clerk’s arduous birthing of development when one can make and change the status quo on their own – doing it faster, cheaper and more amusingly, no less? It is a question about the possibilities embedded in public space, not about the impossibilities of life. A spatial experiment such as the one enlivening the central square of Paide is the best kind of evidence available to indicate that it is possible to switch viewpoints – the joy of doing it yourself becomes visible to the outside and may even infect others.

White. Communication Space for a Community

The same study on small settlements asserts: analyses of prosperous economies have identified factual links between so-called social capital and development. Numerous organisations and tight communication create an environment where economical ties, sharing of knowledge and innovation function smoothly. The formula for co-existence and joint activity is simple – standing together develops in a local communication space.1 Every municipality relies on community initiatives to build the white ship of hope that would steer everyone to a bright and happy future.

Paide is a town with a longstanding history of third-sector initiatives, including founding of local currency (by the Weissenstein union and named “P.A.I.“ (“pai“ – caress), appreciating voluntary work), activating the old town; it houses the youngest professional theatre of Estonia and a gigantic culture centre buzzing like a beehive, not to mention the experience gathered during the seven years of organising the volunteer based Opinion Festival.

The concentration of the so-called “bright sparks“ and the spirit of collaboration seems high in Paide. That makes it a natural springboard for Estonia’s largest (by dimension and duration) spatial experiment that grew to last from a month to two months, and gives the central square back to the citizens, whilst seeing the entire building and decorating set up as contribution through voluntary and communal work. The foremost task of the collaborating architect is translating the dreams and wishes of the community into spatial language and keeping it all together.

The purpose of spatial experiments is to act as agents for communal cooperation for different groups of society. The initiative that gathered momentum in Paide has become a solid example of successful placemaking, leaving no trace of doubt: just create a space, and the users will come. Each year something has changed, been added, showing that an experimental mindset is the way towards a better shared space.

Grey. Transportation and Infrastructure

An online discussion on social media prompted the question whether a town the size of Paide even has public space or whether it is just a junction in infrastructure. Indeed, what makes the public space of a small town?

A neglected public space tends to turn grey, the colour of asphalt and habits from who-knows-where. The greyspace of Paide converges at the heart of the town. The former market square, embellished by a church at the one end and Town Hall at the other, has become a traffic junction, cars circle around the small flag square, surrounded by parking spots. Traffic is light, causing the bleak and bare asphalt field to appear even more wasteful. The positive side of an excessively large space is that it can also house a lot of good when redesigned appropriately – two-way traffic on the main streets, distinctive urban furniture, an outdoor cafeteria, a stage, playgrounds, a cultural programme, and a youth centre were introduced during the spatial experiment.

It is possible to fight off the greyness and show off the inherent possibilities of a good public space by changing the traffic, that is, not by closing the central square but by reallocating the space more fairly. The true nature of the central square, the magnet for a shared life capable of attracting town inhabitants almost 24/7 despite weather conditions, begins to surface from beneath the technical infrastructure and transport corridor. It is possible to create a cozy place for get-togethers even in the middle of an anonymous field of asphalt.

Shades. Capital of Opinions

Any small town can use their intrinsic uniqueness to showcase a deep-rooted industrial manufacturing tradition or an attractive historical object (a castle, a manor, etc), or develop an activity or event (such as skiing, a folk festival, etc) to be recognised at international level.1 The most special event at Paide is the Opinion Festival, which brings together an extremely versatile group of people with the joint purpose of developing democratic discussion and inspiring change. After three spatial experiments carried out in the same spirit, the time is ripe for an architectural competition to find a new spatial solution for an intact, human-friendly central square.

Preparations for the contest have startled many opinion owners to speak up. For some, the spatial experiment is akin to strangling a boa that loses its life in Paide and one should not experiment with space like that – since urban space evolves on its own over time, somehow, depending on the circumstances2. Others think a pedestrian-friendly central square could be the town business card – Paide municipality has had the guts and wits to place people ahead of cars with the experiment, and claims about people no longer being able to commute in the square or the adjacent streets or find anything at all, only prove a case of learned helplessness3. Heated debates indicate that the central square matters and a broader discussion is a (somewhat painful) journey that must be undertaken to reach a better version of public (communication) space.

Colourful. Timbu-Limbu-Land4

Paide central square hosted the first spatial experiment in 2017 when Ott Karulin as member of the Opinion Festival organising team introduced the idea to extend the urban commotion produced by the festival so locals could gain more access to the otherwise two-day event. The head of the Opinion Festival grounds Maiko Kesküla involved the community and together a month-long installation of a human-friendly space (architect Elo Kiivet) was designed and built in the central square. The purpose of the test space is to show that simple and sustainable solutions are a means for the local citizens to radically improve their urban space. This way, the experiment becomes a spatio-educational project to fortify the community and show better uses of shared space.

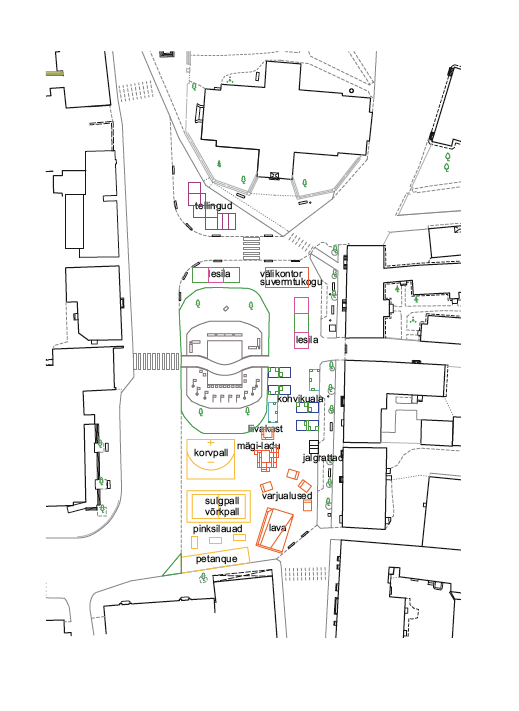

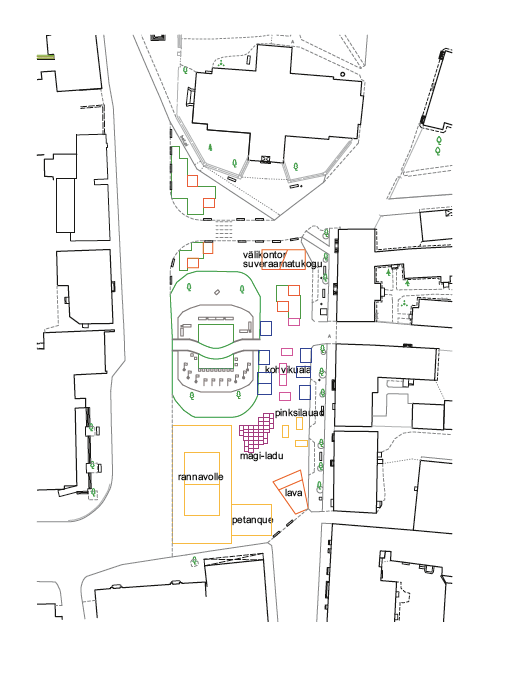

The spatial experiment of Paide regards the centre as the common living room for town inhabitants, meant for meeting one another, furnished by nests for communication, action and simply being for the big and the small, the elderly and the young. The first two years, the entire furniture was built out of wooden pallets that were either borrowed or later sold back to save time and money. A bigger budget in 2019 enabled building more durable furniture and a larger stage. Urban furniture was interlaced with grass islets, an outdoor office-slash-summer library (a stage built and reused for the festival by students of the architecture department of the Estonian Academy of Arts), a roofed stage, a sports area for ball games, a mount usable as an auditorium and storage room, a scaffolding turned play- and climbing installation with swings, a sandbox, recycle bins for sorting trash, bicycle depots, flower boxes for traffic separators. The entire furniture was built so that it could be dissembled, transported and stored for many summers.

In addition to the built space, a culture programme from the Paide Music and Theatre House and Paide Open Youth Centre (including the youth club) enriched the central square. The majority of the organisers and performers were volunteers, everyone had a free chance to offer events to be included in the programme. During 54 days, about 4,100 people (excluding the visitors of the festival) participated in the cultural programme with 74 events.

The intent is to sustain and develop the test space until the town receives a permanent human-scale central square. The architectural contest for Paide central square was announced on December 2, and the deadline for novel entries is February 12, 2020.

ELO KIIVET is an architect and urbanist, who spent three summers in Paide, building the central square and the Opinion Festival. She is now the part-time city architect of Paide.

HEADER photo by Ants Leppoja.

PUBLISHED: Maja 99 (winter 2020) Rural Insights

1 Study on small Estonian settlements. Hendrikson & Ko, University of Tallinn, Ministry of Finance, 2019. Map application https://planeerimine.ee/2019/03/eesti-vaikeasulate-uuring/#more-3663

2 Kalle Kroon, A few remarks on Paide Pikk Street and the „spatial experiment“. Järva Teataja 26. XI 2019.

3 Paide city youth council, On the possibilities of pedestrian-friendly routes in the town heart. Järva Teataja 28. XI 2019.

4 Kalle Grünthal, Council, hit the brakes. Järva Teataja 3. XII 2019. Title used in the article for the Paide central square spatial experiment.