There is no way to describe the current state of Latvian architecture without at least mentioning the so-called “large cultural buildings”. During the last decade, these have been the words constantly repeated by ministers, city mayors, directors of cultural institutions, and the media.

The cultural buildings, which have overtaken the Latvian architectural debate in recent years are concert halls, libraries, museums, and theatres. These were dreamed up before and during the financial crisis of 2008, and have been slowly coming to fruition over the last few years.

The expectations placed on these products of political ambition and generous funding from the European Regional Development Fund are almost impossible to meet. Not only do the new cultural giants have to satisfy the yearning for contemporary architecture and resonate with the gentle strings of the Latvian soul, they are also expected to kickstart a spiritual renaissance in the country. These buildings are supposed to help raise quality of life in the regions, attract tourists and investment, and perhaps even persuade expatriates to return home. Large cultural buildings are seen as something that we have to accomplish as a nation as they will be our legacy for the generations to come. It is therefore logical that most of these buildings are designed as monumental landmarks — impressive in scale, sculptural in form, and charged in their imagery.

Music in the regions

The first regional concert hall to open (2013) was Gors in Rēzekne, designed by Vizuālās Modelēšanas Studija. It surprised the public with a large, angular volume, bold colours in the interior as well as the local-patriotic name Gors, which means “spirit” in the Latgalian language spoken in the Eastern part of the country. The town of Cēsis in the Vidzeme region opted for a different strategy — to re-use its old culture centre by incorporating it into a concert hall. In this small medieval town, the concert hall’s offices can be considered a high-rise, clad in glass and with decorative shutters painted orange, a signature colour of the architecture firm Arhitekta J. Pogas Birojs.

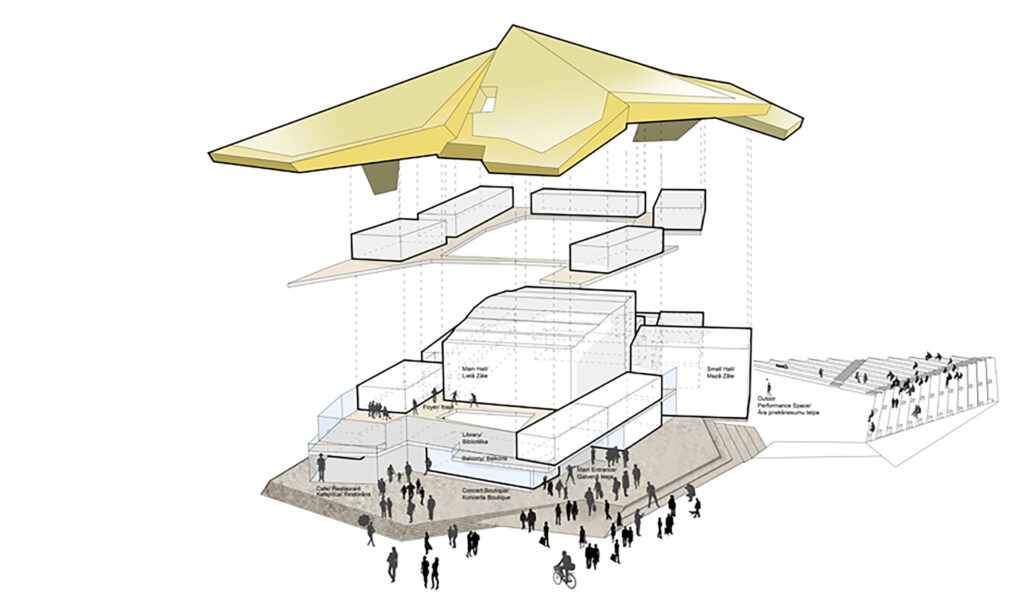

Arguably, the most distinctive of the five regional concert halls is the Great Amber (2015) in Liepāja, designed by Austrian architect Volker Giencke. The symbolism here is quite literal — the orange-tinted glazing is a nod to the gem of the Baltic Sea while the stair labyrinths comparable to a cruise ship’s pay tribute to the role of Liepāja as a port city. Despite obvious flaws in its layout and detailing, the expressive volume has proved to be highly instagrammable and managed to seduce architecture lovers around the world.

In contrast, the Dzintari Concert Hall (2015) in Jūrmala added only a light entrance pavilion and an underground lobby to an accurately restored 1930s wooden heritage building. The architects, Jaunromāns un Ābele, have designed the interiors as a gradual transition from minimalistic transparency to the saturated wooden panelling of the chamber music hall.

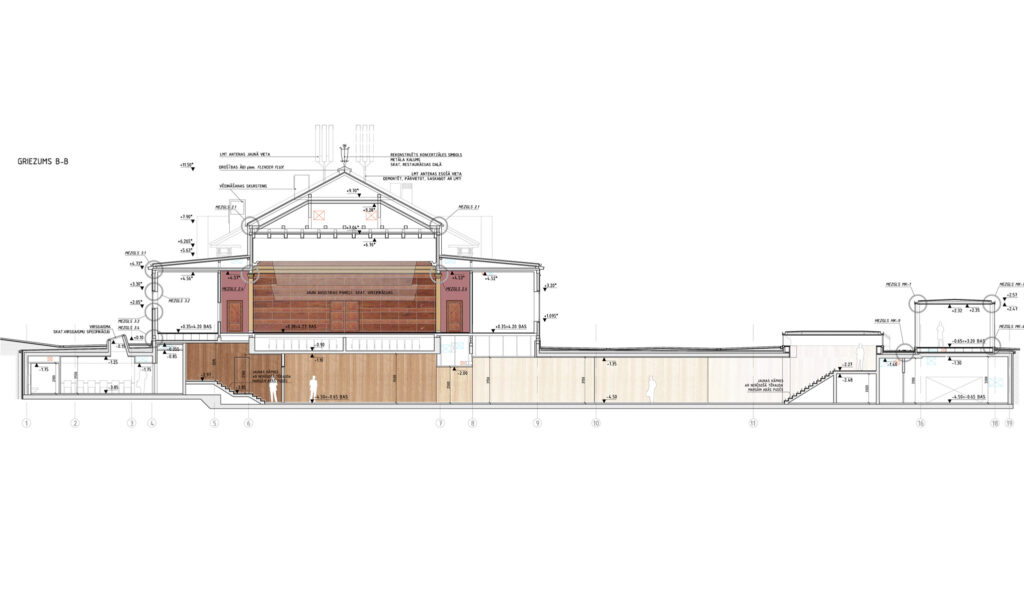

Finally, the concert hall Latvija, which opened in Ventspils just last year, has received mixed reviews. There are two things that stand out about it: its vast deconstructivist roof and highly progressive energy concept. The former is a characteristic gesture of Behnish Architecten who started the project, and the latter — a passion of haascookzemmrich STUDIO2050, a spin-off of Behnish, who completed it.

Undoubtedly, the new concert halls have raised the self-confidence of regional centres, provided the warm and well-lit spaces needed for cultural creation and musical education, enriched urban landscapes, and created new gathering places for local communities. The new architecture has solved acute needs and fulfilled cherished dreams of many, but more could have been done to make it more sustainable and fitting for the local context. The ultimate test is still ahead of us — the Riga Acoustic Concert Hall has been a subject of discussion for more than 10 years, and recently a new site has been proposed for it.

National Library

The most significant of all the “large cultural buildings” by far is the National Library of Latvia, a colossal effort that took 25 years of planning, debating, designing, building, moving, and accepting. A need for a centralised National Library, previously scattered in numerous buildings across the city, arose already in the 1980s. In 1989, the internationally acclaimed Latvian-born architect Gunnar Birkerts was tasked to design the library. He delivered a sketch loaded with metaphors referring to the rebirth of an independent Latvian state, Latvian literature and nature. Construction began only in 2008, and when the library finally opened in 2014, it caused such a bittersweet euphoria that neither local architecture critics, nor the international jury of the Latvian Architecture Award were able to give it a proper evaluation.

With a floor area of over 42,000 square metres, the building rises like a glass and steel mountain on the left bank of the river Daugava. Depending on the time of day, both of its official aliases, Hill of Glass and Castle of Light, are fitting descriptions. The interior is a peculiar mixture of Birkert’s fond memories of his homeland and professional experience in designing corporate offices in American cities. The distant and cold impression of the ground floor is softened by cosy carpeting and furniture of the reading rooms above. One of the more impressive features of the library’s atrium is the “People’s Bookshelf” — a five-storey-high assemblage of books gifted to the National Library.

The Castle of Light has transformed not only the urban, but also the cultural landscape of Pārdaugava, the part of the city on the left bank of the river. Students flock to the reading rooms to study, the landscaping around the library has become a popular spot for skaters, and the glazed spire on the 11th floor is perfect for press events. But most importantly, the library has become a welcoming host of exhibitions, conferences, and other social gatherings.

National Museum of Art

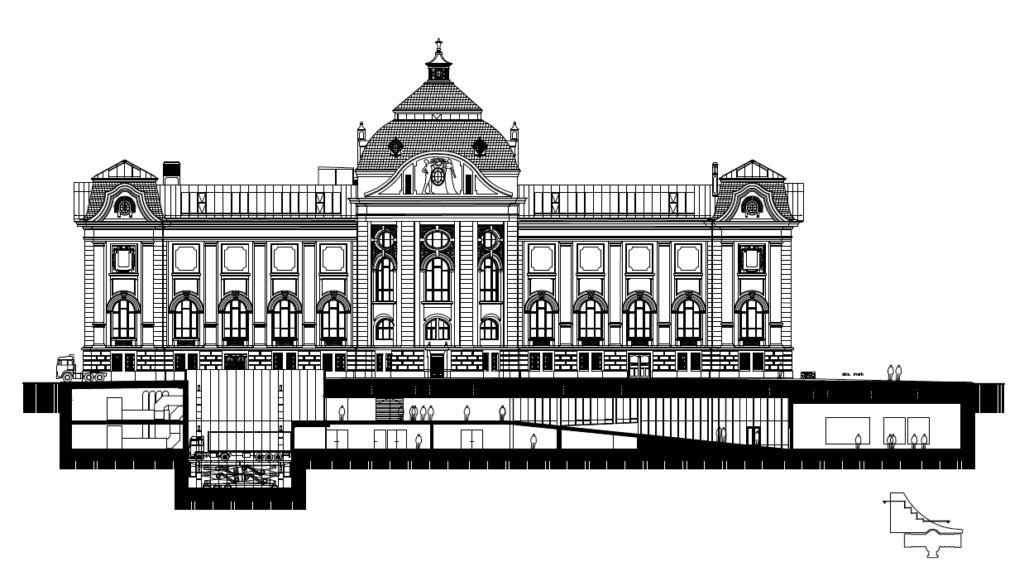

Shortly before the National Library opened, another cultural heavy-weight, the Latvian National Museum of Art closed for renovation. Inaugurated in 1905, the neo-Baroque building of the museum is a prominent landmark of the city centre. It was designed by the German architect and art historian Wilhelm Neumann who also served as the museum’s first director. The museum’s permanent exposition provides a comprehensive overview of Latvian painting in the 19th and 20th centuries, while temporary exhibitions feature works of recognised contemporary artists.

In 2010, the Lithuanian firm Processoffice won the international competition to redesign the museum. After learning about the results, many local architects turned sour, complaining about “a missed opportunity to create architecture with a capital A”. The Lithuanian team had proposed an almost invisible intervention — clearing out and retrofitting underused spaces of the historical building and placing the new 3,500 square metre annexe underground. This would ensure that the surroundings of the museum remain intact apart from a new public square featuring a slightly submerged glass rectangle that delivers light to the rooms below.

The museum’s new extension connects to Neumann’s early 20th-century architecture discreetly and respectfully while the refurbished main building now offers a range of spatial adventures: an all-white cupola hall with intricate timber constructions, rooftop terraces with panoramic views of Riga, and see-through floor segments. The museum, which had hitherto turned its back on the Esplanade Park, now opens up to it and entices visitors into the building through the café. With the restored facade finishing, the building has gained a majestic and even contemporary look, while the interior is unobtrusive and airy.

In December 2015, the museum’s administration organised a few open days providing a rare opportunity to see the freshly renovated building before art had been placed on its walls. Around 125,000 people queued up to browse the empty rooms — more visitors than the year before the renovation! As architecture critic Ieva Zībārte points out, the museum has now become captivating not only by its programme, but also by its architecture.

While the issues of exhibiting and storing 19th and 20th century paintings seem to be sorted for now, contemporary visual art is still missing a suitable venue. An ambitious international competition was held in 2015 to design a Contemporary Art Museum in the developing New Hanza City in Riga. Foreign architects had to pair up with a Latvian partner to enter the competition, and eventually Adjaye Associates in partnership with AB3D were selected as winners. From afar, their proposal would resemble a small village of timber-clad houses, with pitched gables turned towards north light. The project is currently completed, but it remains unclear whether the construction of the building will start any time soon.

Refounded heritage

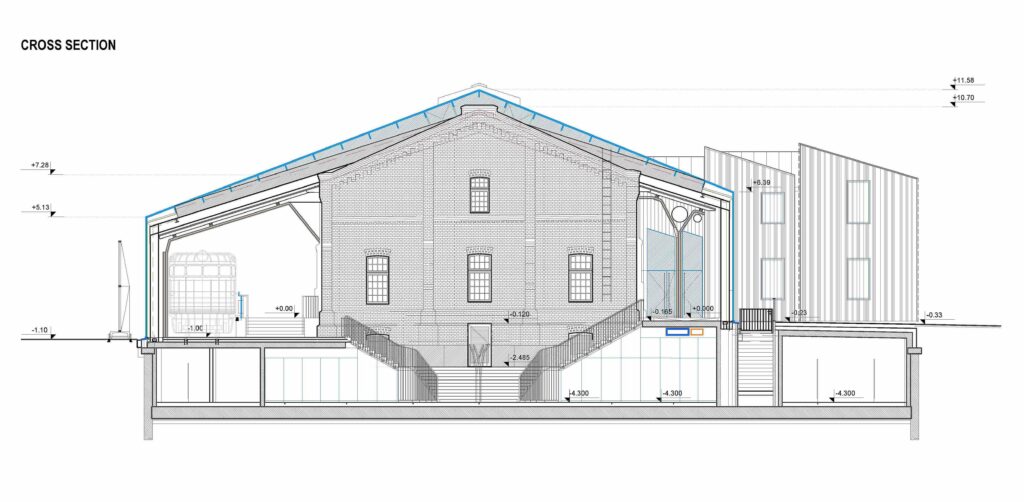

In the meantime, one of the corners of New Hanza City is now demarcated by a smaller cultural venue, Hanzas Perons, that opened in 2019. It occupies a former freight railway station, a fine example of industrial brick architecture built around the beginning of the 20th century. Sudraba Arhitektūra, an office specialised in restoration, renovation and retrofitting of heritage buildings, was selected for the design job. In order to adapt the space to today’s requirements of energy efficiency, the historical building was dressed in a glass “coat” with an occasional layer of timber slats for shading. This protects the old building and transforms the train platforms into convenient lobbies. Carefully restored brick walls, massive structural elements, sliding doors and gates of the old warehouse dominate the interior of Hanzas Perons and provide an appealing scenography for a wide variety of cultural and entertainment events. The event industry had long awaited a stylish and easily transformable space to become available in Riga, and the calendar of Hanzas Perons quickly filled with concerts, theatre and dance performances, trade shows, conferences, and celebrations.

Authors of the renovation emphasise that their approach is sustainable and in line with Riga’s UNESCO World Heritage Site status. It is a belief shared by many, and restorations and renovations have indeed proven to be a forte of architects working in Latvia.

In 2018, the winner of the Latvian Architecture Award was the 1st State Gymnasium of Liepāja, a careful and lengthy renovation of an Art Nouveau school building. The construction works were carried out in over 30 phases, mainly during school summer holidays. Author of the project, Ilze Mekša, praises the client — the school’s administration — for its commitment to creating a contemporary learning environment and productive communication. When the architecture carries so much tradition and meaning for the local community, repairing the building alone is not enough.

A few years prior, the architecture office of Zaiga Gaile received similar recognition for the renovation of Riga School of Design and Art, the oldest wooden school building in Riga. The purpose of the project was to provide an outstanding example of the unique qualities of wooden buildings and a contemporary approach to their renovation. The architecture of the early 19th century building was restored as close to the original as possible, including the symmetrical floor plan and exposed lumber walls. Two new staircases, glass partition walls, and contemporary skylights are contemporary additions to the building. These are simple and clean designs, without attempting to copy or interpret any historical details. As the building has never had central heating, original woodstoves were preserved as fully functional elements. The pleasant atmosphere in the building results from many small, yet carefully considered decisions, and the presence of art and design students.

Zaiga Gaile’s efforts to bring awareness to the value of historical wooden architecture has not gone unnoticed — the society’s attitude has changed for the better. Kalnciema Quarter, a cluster of renovated wooden buildings in Riga, is now a popular hangout, as are the neighbourhoods of Grīziņkalns and Ķīpsala, the whole historical centre of Kuldīga, and many more. Living or working in a well-preserved wooden house is now a desired lifestyle.

Hills, trees and the secret of levitation

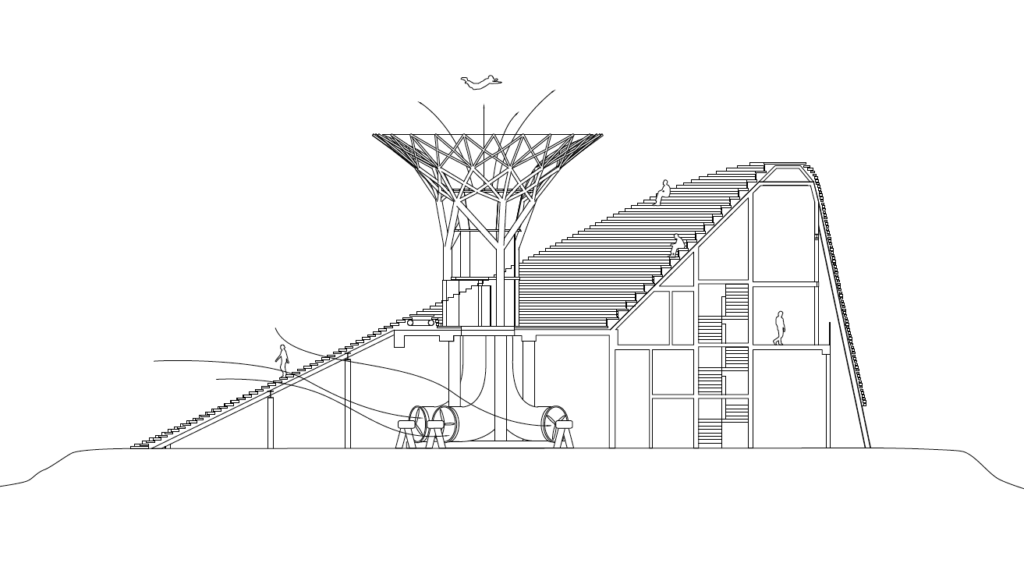

In 2016 an unusual project was completed on Chinese soil by a young Latvian architect, Austris Mailītis. The function of the Flying Monks Theatre is conceptually based in levitation, the secrets of which have been studied by Buddhist monks for centuries. Shaolin, where the pavilion stands on a hilltop, is considered to be the birthplace of Zen Buddhism and kung fu martial arts. Drawing inspiration from the local nature and culture, Mailītis designed an open–air amphitheatre whose architectural form unites two symbols — a mountain and a tree. A hidden vertical wind tunnel inside the “tree trunk” makes levitation physically possible and entertaining for the audience sitting on the steps of the exterior surface. The stairs, apart from their usual purpose, are designed to continue the natural topography, to adjust natural lighting for the interior and to deliver a strong air flow for the engines. The technology was initially developed by the company Aerodium for the Latvian Pavilion in Expo 2010 in Shanghai.

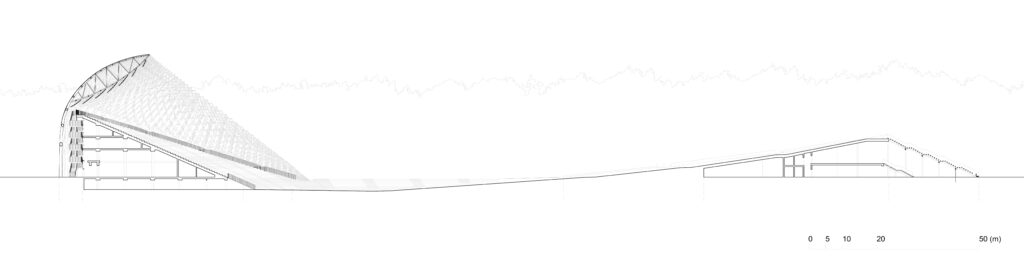

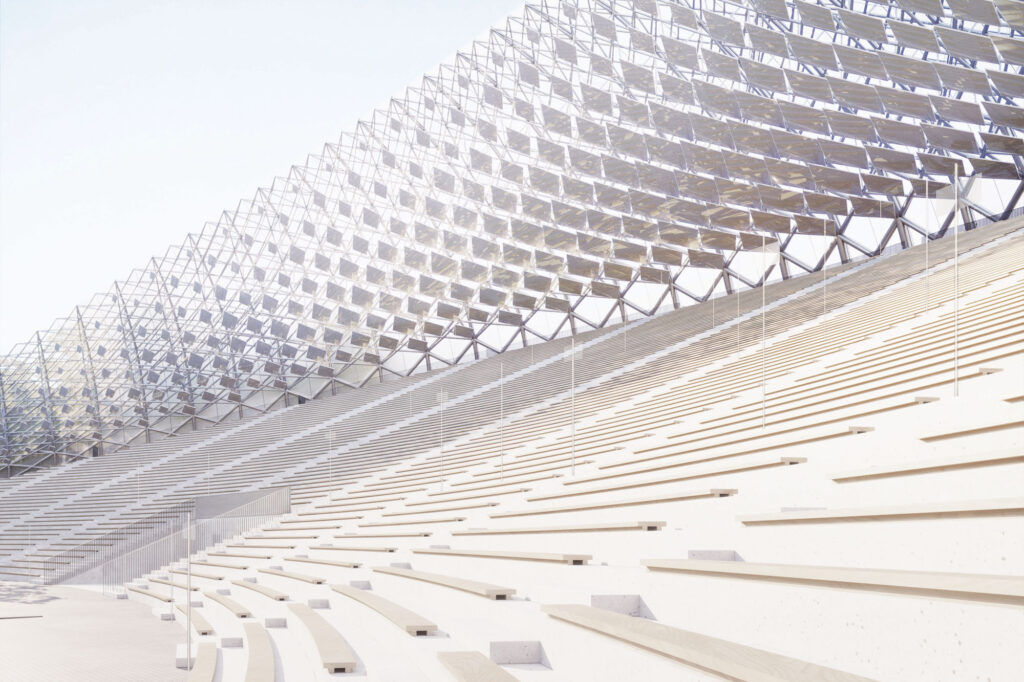

Intentionally or not, the Flying Monks Theatre has served as a prototype for a much bigger project — the Mežaparks Open-Air Stage where the Nationwide Song and Dance Festival takes place every five years. The project’s aim is to significantly expand both the stage and the audience seating area, add new facilities and reinvigorate the venue’s image. Mailītis Architects together with Arhitekta J. Pogas Birojs developed a concept of a tree-lined hill where the Latvian people would gather to sing and dance. The steel mesh above the stage symbolises a silver birch grove, mentioned in many Latvian folk songs. The “leaves” of the trees serve as sound reflectors and scenographic elements. All the amenities needed for such a large-scale event are now hidden underneath the spectators’ seating area, thus relieving the surroundings of pop-up tents and kiosks. The massive renovation has already begun to take shape: the spectators’ side is finished, and the stage is expected to be ready in summer 2020.

Dialogue with the public

Over the past five years, Latvia has witnessed a surge in public interest in urban design and activism, largely due to organisations like “Pilsēta cilvēkiem” (City for People). Made up of architects, cycling enthusiasts, and neighbourhood activists, it advocates for higher quality urban environment, safer road infrastructure, and universal design. The group has gained considerable traction on social media and established a reputation of a watchdog of municipal projects, pointing out mistakes and providing recommendations for better design. Their most recent activities include organising car-free Saturdays in some streets in central Riga as well as the planting of trees to demonstrate that it is feasible even in pavements with dense utility networks underneath.

While “Pilsēta cilvēkiem” fights its battles online and on the streets, TV remains a highly effective tool for bringing visual content to people on their sofas. With a background in media and advertising and a keen interest in history and architecture, Mārtiņš Ķibilds created and hosted the TV show “Adreses” (Addresses) for four successful seasons. The programme featured both architectural successes and failures, usually comparing two buildings in each episode. Ķibilds’ inquisitive and cheeky presentation style quickly gained popularity as he didn’t shy away from asking naive or provocative questions about newly built, renovated, and heritage buildings. With the help of “VFS Films” crew he accomplished what architects had been trying to do for years — to excite curiosity in the general public about architecture. Sadly, the fifth season ended abruptly when its creator suddenly passed away in October 2019. He has surely left large shoes to fill.

Together and apart

There is no doubt that in the recent years, culture in all its various forms has been the main driving force behind good architecture and public space design in Latvia. But are there any other incentives to create well designed buildings and outdoor spaces?

Entire quarters and neighbourhoods have appeared in Riga and some other cities. The most noticeable and publicly discussed new development areas of the capital are Skanste and Jaunā Teika. While Skanste has been critised for its outdated autocentric layout, Hanner, the developer of Jaunā Teika seems to have invested thought and resources into creating a mix of different uses and designs of public squares.

The outcome, in both cases, is rather generic office and apartment blocks catering mainly to the needs of middle-class residents looking to buy. While the need for affordable rental housing has surged in both Riga and regional centres, there is hardly any urgency in the political or architectural discussions about it.

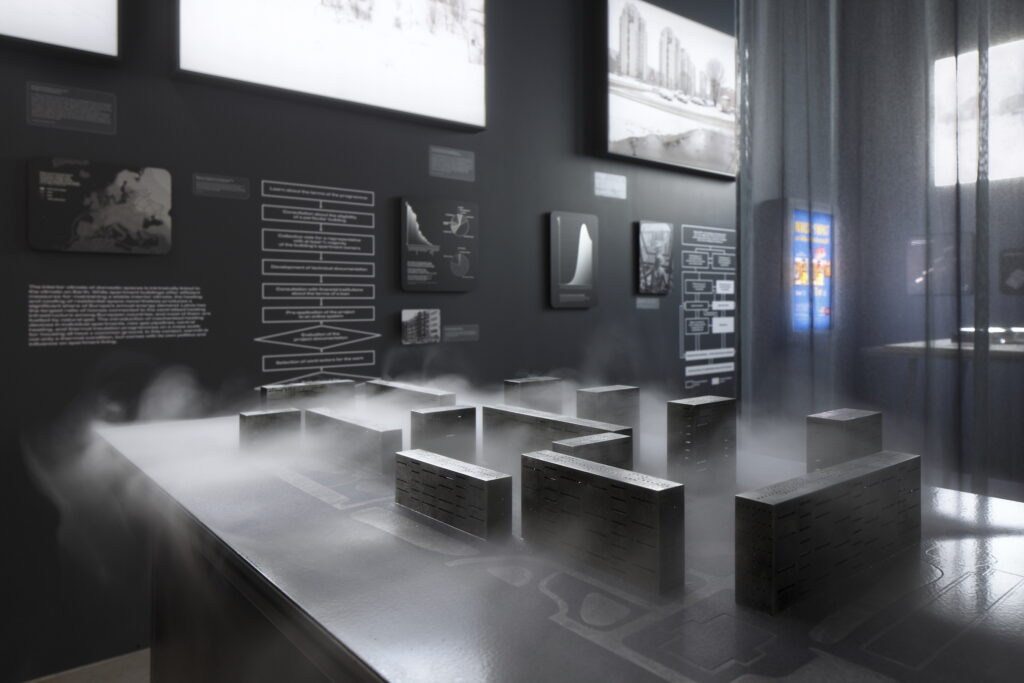

Housing and, more specifically, apartment buildings (the most common type of dwelling in Latvia) were the focus of the Latvian Pavilion “Together and Apart” at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. Authors of the exhibition (Matīss Groskaufmanis, Gundega Laiviņa, Evelīna Ozola, Anda Skrējāne) used the occasion to bring attention to the issues of affordable housing, renovation of the existing housing stock, and housing for vulnerable social groups. In their exhibition, public talks, and two released books they stressed that architects should be more vocal and inventive with regard to improving housing conditions in Latvia. In a country as small as ours, the well-being of each resident matters. Collectively, we should move on from a situation where good architecture is a luxury to be enjoyed only when attending large cultural buildings or by browsing magazines featuring expensive villas towards a decent standard of spatial design in our nearest everyday surroundings — our homes, schools and workplaces, the streets and squares of our cities.

EVELINA OZOLA is a Latvian architect, urban designer, and editor. In 2018, she co-curated the Latvian Pavilion “Together and Apart” at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Header: Latvian National Library, architect Gunnar Birkets, 2014. Photo by Reinis Petersons.

Published in Maja’s 2020 spring edition Maja 100! (No 100).