Indrek Allmann discusses landward- and seaward-facing small harbours.

All islands have one fundamental thing in common: they are surrounded by water. This water might be exploited for recreation as well as fishing, but above all, it is a space for mobility. For as pleasant as it may be to stay on an island, at some point you are going to have to leave. Islands are connected by waterways, which are really nothing but maritime siblings of land roads. They differ simply in their environment and the means of transport used. Smart use of waterways enables islanders to perceive the spatiotemporal component of mobility space in a very different way than those who move only on dry land. Thus, in fair weather, the islanders of Hiiumaa can reach Sweden by a motorboat in about two hours (84 nmi from Kalana to Svenska Högarna), almost in the same time as Tallinn (74 nmi from Heltermaa to Vanasadam), whereas Finland can be reached in only about an hour (50 nmi from Kärdla to Hanko eastern harbour) and Kihnu in about the same (57 nmi from Heltermaa to Kihnu). When the weather is rough, however, everything is different and travelling the same routes could take days.

While 15 years ago, there were around 16,000 recreational craft in Estonia, the number of registered craft has now risen to 34,000. There has been a constant increase by 1,200 craft in a year. Also, the size of the craft has changed. While most boats used to be of the 4.5–5.5 metre class, the average craft today is significantly seaworthier—at least 7.5 m long. At the same time, the increase in the number of berths has been ten times slower, which has led to a deficit and severely hampers further maritime development. Due to the lack of mooring places, many have no other option than to keep their boat on a trailer in their backyard. This in turn means that to move the boat, they need to have a larger sort of SUV. According to the Association of Estonian Marine Industries and Small Harbour Competence Centre, there are altogether 3500 berths in Estonian harbours. Granted, there are also unregistered domestic jetties, but the number is still ten times lower than the number of boats. Compared to Finland and Sweden, these figures are extremely small. For example, the harbour of Bullandö alone, which serves as a connection with the surrounding islands, has more than 1400 places for watercraft.

Just like there are different people, there are also different harbours. The most important point of difference lies in whether the harbour has been designed to face towards land or face towards the sea. Landward-facing ones tend to include all the ferry ports, the purpose of which is merely to get the passengers quickly and efficiently on the ferry and take them to a similar destination, where they are quickly driven out again. There can also be landward-facing small harbours, whose restaurant and sunset-lit pier or viewing platform are visited in the same manner you would visit, say, the foyer of a modern opera building, and without any desire to head out to the sea. A landward-facing small harbour looks nice and occasionally romantic when approached from the land, but its fairway contains more sand than water.

A seaward-facing harbour strives to have a strong influence on the planning on land. In such a harbour, wind turbines or roof ridges form a leading line demarcating waterway, and upon entering the harbour basin, you can immediately figure out which berths are meant for visiting vessels, which berths are there for the residing ones, and where a boat that has suffered an accident could moor and get out of water. The restaurant in a seaward-facing harbour is placed in a way that enables a visiting yacht owner to see the swaying mast of their sailboat; there is no need to rent a bicycle to get to the toilet or washing room; the sauna is placed so that you can go swimming from there; there are picnic shelters and fully equipped barbecuing spots near the visitors’ berths, and one does not have to go through code-locked gates while carrying heavy supplies or repair equipment to get to one’s boat, because the plan of the harbour itself discourages ignorant landlubbers from hanging around the floating docks. Granted, there are also some examples that go over the top—harbours where the docks and the nearest building are separated not by cosy picnic tables and an outdoor gym, but rather by a huge asphalt lot, because, well, maybe some historical sailboat will someday happen to drop by and want to dry its large sails there, and also, it is nice to have all the sailboats lined up there for the winter, instead of having to drive them around the corner. Such overeagerly seaward-facing harbours are actually faced towards ‘shore admirals’, I suppose.

Harbours in Estonia have usually been considered merely from the technical engineering perspective, and thus, little attention has been paid to formulating the user needs or designing the user experience. It is no wonder, then, that the people of Vilsandi have to take their small boats to the newly renovated Papissaare harbour, which was once built with the needs of large fishing vessels in mind. The needs and desires of modern users were not analysed before the reconstruction commenced. Or take another example. If the reader has ever felt confused by or even lost in Rohuküla harbour, know that this harbour was designed in the Tsarist era for warships. Later it has been tweaked one quay at a time, without ever reflecting more broadly on what kind of comprehensive plan would correspond to its changed use. One of the consequences is that every time the southerly wind gets a bit stronger, the people of Vormsi are left without a ferry connection.

Six years ago I was invited to join the board of AS Saarte Liinid, a state-owned company that manages 18 ports. These are the ports that connect almost all of the permanently inhabited Estonian islands. After thoroughly working with people in the company and making some unavoidable personnel changes, we launched the first public architecture competition of AS Saarte Liinid in collaboration with the Estonian Association of Architects for extending Kuivastu recreational craft harbour into a regional service centre. Working with the management of AS Saarte Liinid, architect Kalle Komissarov put together a thorough competition brief. The purpose of the competition was to analyse different user groups and propose a comprehensive plan that would face towards both land and the sea. A characteristic feature of Kuivastu as a location is that there is practically no local population to whom the harbour could offer local services. Thus, almost all of the users either come from the sea or are going to the sea. The competition attracted much attention and there were 16 submissions.

Much to the surprise of the jury, nearly three quarters of the submissions were drawn so that they were squarely facing away from the sea. The existing harbour had been rendered functionally unusable in various sections. The main focus was on designing the harbour building, in the size of a larger residence, without paying any attention to what it is actually used for. The amount of bicycles and people on more fanciful illustrations suggested that the architects had a very peculiar and unrealistic vision about the number and nature of the harbour’s users. Nevertheless, the jury did not disregard these works and instead analysed whether such a radical turn towards land was due to some earlier ‘admiral’-like decisions in the design of the existing harbour. The supervisory board of the company agreed to consider changing the harbours’s water structures if necessary, however, as this would be a costly action with extensive environmental impact, it would require to be exceptionally well justified.

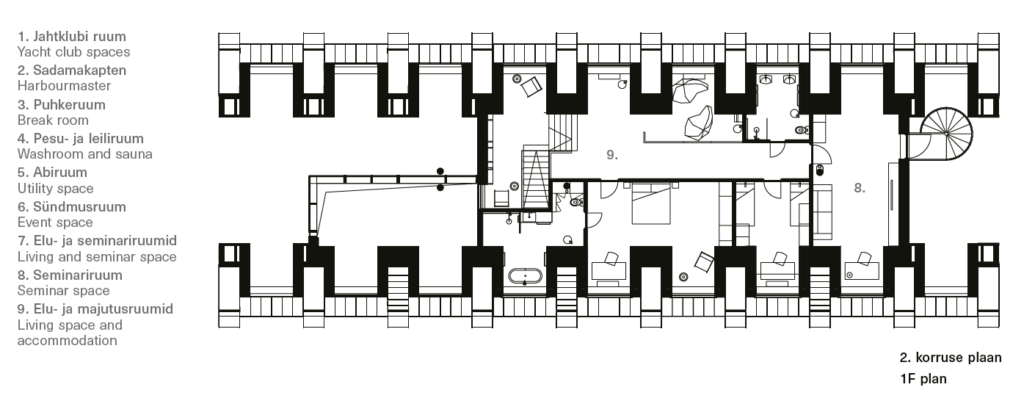

The competition was won by architecture office Arhitekt Must, whose submission managed to strike a balance between existing facilities and the needs of various user groups. Naturally, such a compromise did not satisfy the passionate ‘admirals’ who use the slipway a couple of times per year, and this led to all sorts of nonsense being written about the winning work on the pages of the local newspaper Saarte Hääl. This is in itself speaks of the complexity of the task, I suppose.

However, not all the island harbours are state-owned. Many belong to municipalities or private capital and are managed by various non-profit organisations. There are also some rare instances of private harbours that are open to the public, owned by people with a prosocial mindset. A large boost to the development of small harbours has come from fisheries funds and tourism development measures. It has been interesting to follow the choices of local communities in using these grants. Some communities have invested all the money in harbour structures, whereas others have first built a building where they could simply come together.

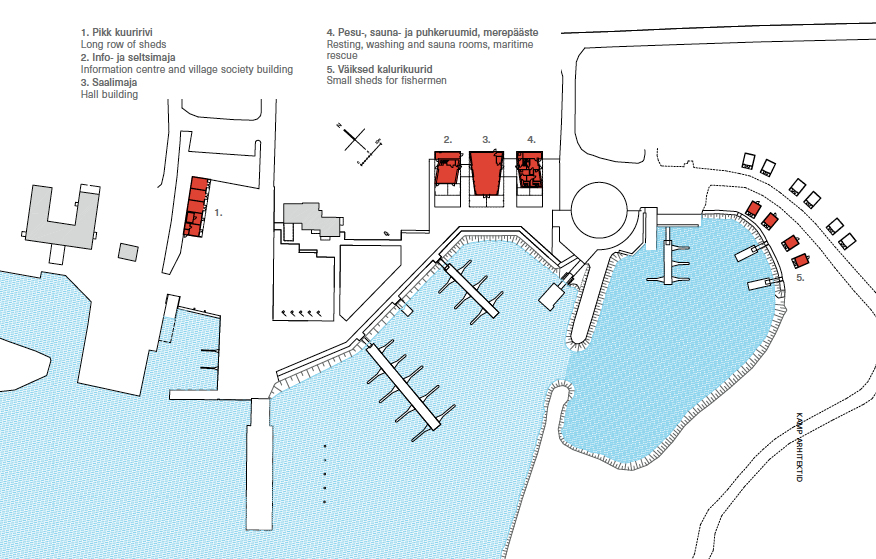

ORJAKU HARBOUR

Architecture: Kamp Architects

Location: Orjaku, Hiiumaa

Harbour building

Client: Orjaku Village Society

Total area: 300m2

Completed: info building 2012 , hall building 2013, washing- and resting building 2020

Ancillary building

Client: Käina Council

Total area: 100m2

Completed: 2012

Small fishing sheds

Client: SA Hiiumaa Sadamad

Total area: 17,9m2

Completed: 2020

The buildings of Orjaku harbour were built in several stages. The long row of sheds was completed in 2012; the tripartite harbour and village society building was completed in three stages — in 2012, 2013 and 2020. Small sheds for fishermen were completed in 2021.

Speaking of more comprehensive solutions, some harbours on the coast of Väinameri come to mind, such as Soela (buildings designed by Vahur Sova) and Orjaku (new buildings designed by Kaspar Kruuse from Kamp Architects). They are similar in that their basins are used in lively and varied ways. The buildings in Soela are more modest, focusing mainly on boathouses and a tiny cafe that have been brought together into a single volume. A little bit further away, a slipway building is still under construction. Orjaku is more multi-layered and pretentious. Harbours that have been able to find a brand for themselves are more attractive to visitors. Who wouldn’t know Sõru Harbour, the site of Sõru Jazz Festival? An undisputed highlight of Orjaku is the Garfish Festival—an event that brings together people from both land and sea, recreating the harbour each time as an interactive environment. I consider comprehensiveness to be the strength of this harbour. It relies on a good plan for the harbour’s basin, good arrangement of outdoor areas and good placement of buildings, making it possible to serve visitors who come to the harbour with very different kinds of desires. To a bystander like me, all of it appears to have been achieved in an affordable way for the community—it does not overburden them with its maintenance needs and enables to focus on the events within and around the architecture. The architecture itself is clear and archetypically robust. Its structure is intelligible even for, say, a child who is visiting the harbour for the first time and is looking for a toilet. A substantive strength of Orjaku lies in the existence of a strong local community, which is also evident in the number of organisations operating in the harbour. It accommodates NPO Orjaku Village Society, Hiiumaa Harbours Foundation, NPO Hiiumaa Voluntary Maritime Rescue Society, as well as local village fishermen. One novel idea was to give building rights (together with a standard project) to those wishing to erect their personal boathouses there. This kind of move ensures a sense of ownership and frees up the rest of the community from dealing with the needs of some individual. Commendable!

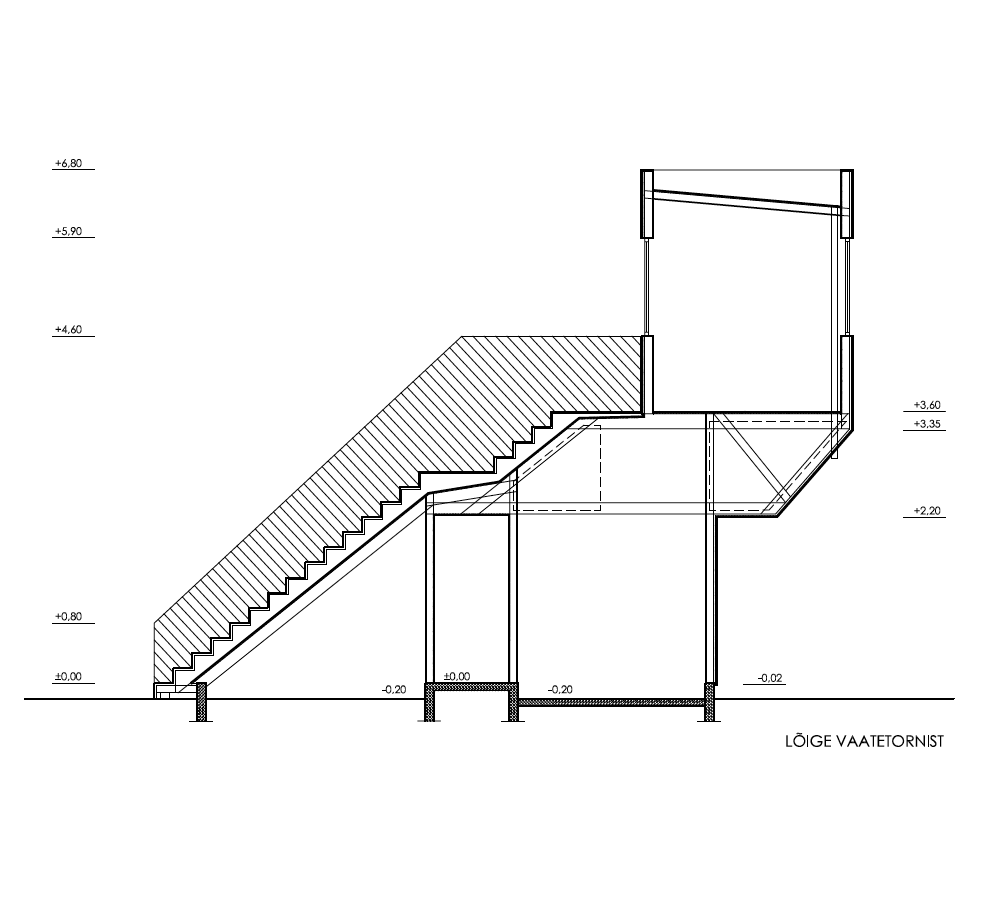

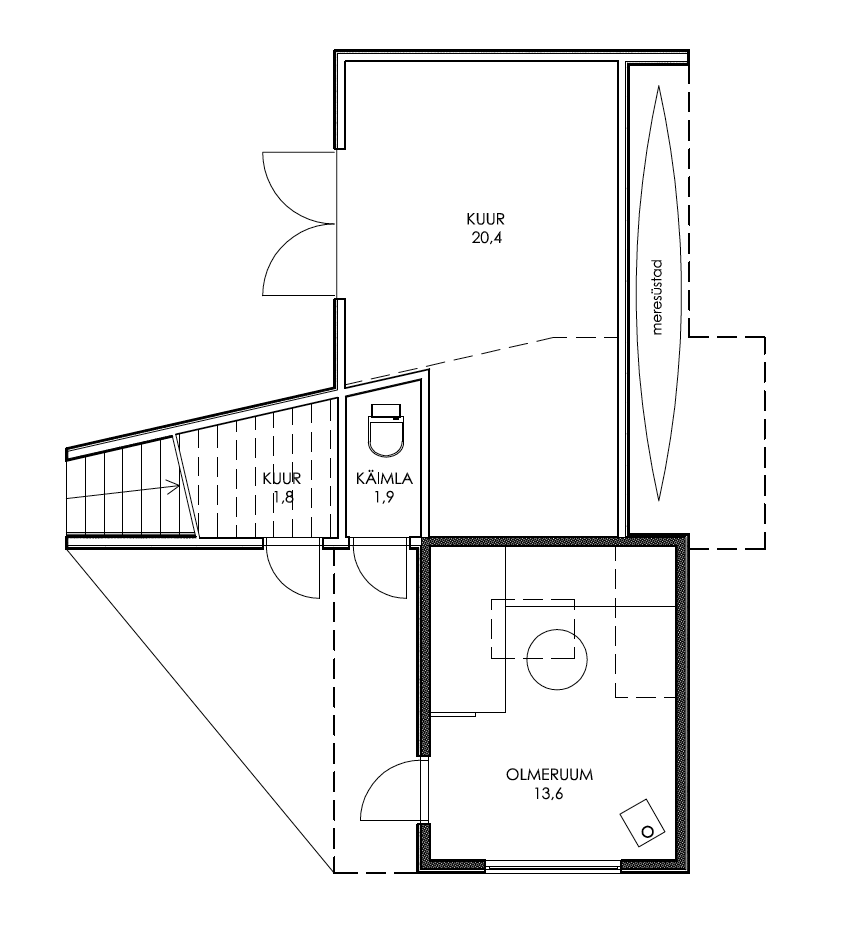

TÄRKMA HARBOUR

Architecture: Kamp Architects

Location: Tärkma, Hiiumaa

Client: NPO Tärkma Harbour Society

Total area: 50m2

Completed: 2013

Tärkma Harbour, situated to the west of Orjaku and once again a work of Kaspar Kruuse, represents a radically different type of harbour. Regardless of its fancy title—a fishing harbour—it is clear right away that it is essentially a development of a domestic jetty, where local villagers can keep their tiny fishing boats. Outsiders, at least those coming from the sea, have no business there. The sea in front of the harbour is just exceptionally shallow and does not support the safe approach of seaworthy vessels. However, outsiders coming from inland are welcome, and can use an observation tower to look across the reed to the sea. The stairs that lead to the tower are robust and spacious, rendering the building reminiscent of an ancient sea worshippers’ temple. Its shape is helpful also for fishermen who are out on the sea—for the most part, our coastal areas are still empty and desolate, making it difficult to navigate by the shore. Such buildings that provide a reference point for the eye are important. Tärkma harbour building charms me mainly with its form and slightly humorous irreverence. What I mean by this is that the building was completed with support from the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund. After all, it does include a small shed where fishermen can keep their life jackets so as not to carry them back home every time—anything helps.

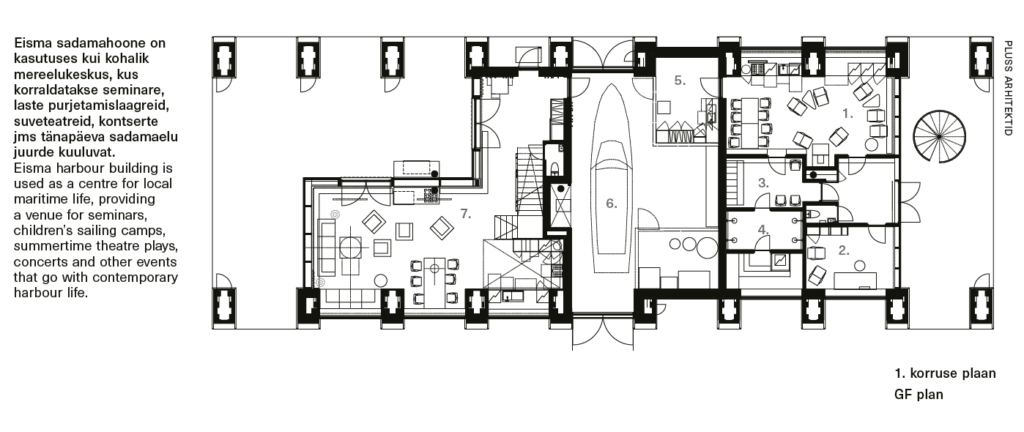

From my personal experience, the most interesting case is Eisma Harbour. In terms of ownership, the project falls mainly into the prosocially-minded private developer category. I was commissioned by a family who had local roots and maritime interests to design a harbour building in a derelict fishing harbour.

The design for the reconstruction of water structures had already been commissioned from engineers and the work was in progress, so it could not be modified anymore. In my work, I took cue from the architecture of a large fishermen’s net shed that had stood in the harbour and for decades served as the landmark of this region for those approaching from the sea. The result was a multi-functional harbour building, which was awarded the ‘Best Home’ prize by the Cultural Endowment of Estonia. This so-called home began to be used by the family as a centre for local maritime life, where they organised seminars, children’s sailing camps, summertime theatre plays, concerts and other events that go with contemporary harbour life. At the same time, the family became increasingly experienced in seafaring and increasingly knowledgeable about what a truly awesome harbour actually needs.

Thus, the next project was born—the so-called ant shed extension along with small additions, which won the small project award in 2018 from the Estonian Association of Architects. The ant shed gave the harbour an emphatically seaward-facing functionality by creating a barbecuing spot for visitors, net sheds for fishermen and small bedrooms for those seafarers whose vessels are not fit for sleeping. The harbour that had initially faced towards land slowly opened up to the sea, which should probably be the ideal for every small harbour, whether it be on an island or on the mainland.

INDREK ALLMANN is an architect and urban planner who focuses on various aspects of environment-responsive building and living. He is a founding partner of Pluss Architects.

HEADER: Tärkma harbour. Kamp Architects, 2013. Photo by Joosep Kivimäe

PUBLISHED: Maja 114 (autumn 2023) with main topic ISLANDS