OUTSET

Curled-Up Coastline 〉Helgi Põllo

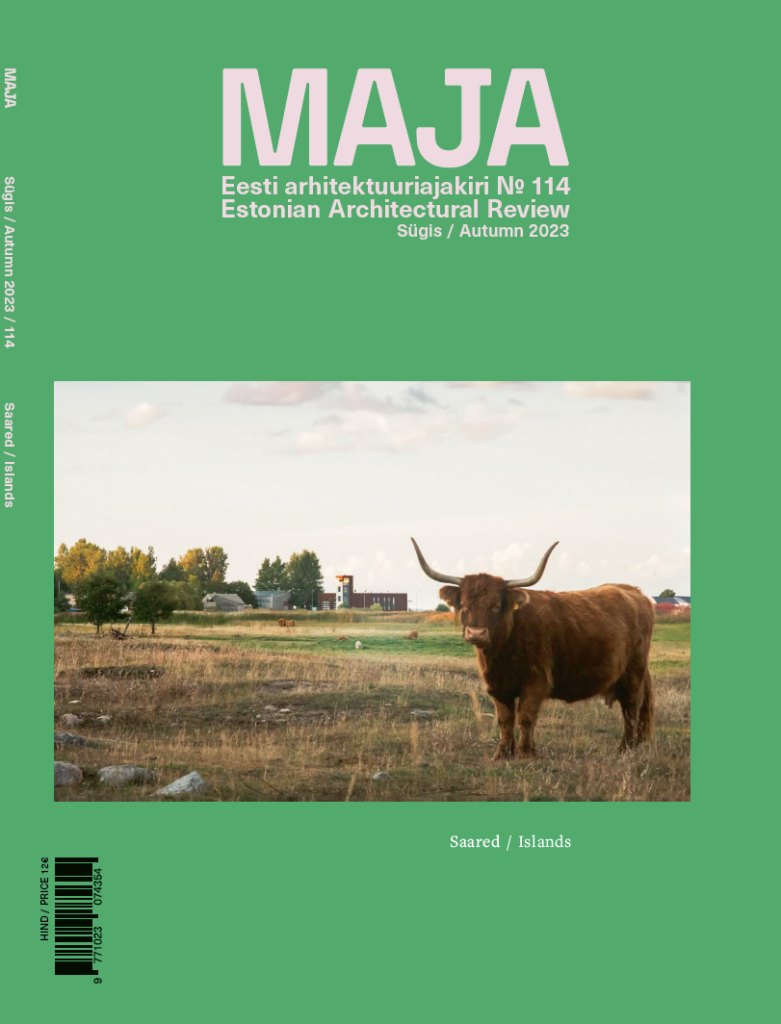

COVER

Kihnu Rescue Building. Studio Paralleel 〉Jaak Huimerind

PROJECT

Hiiumaa General Plan. Hiiumaa, EST. AB Artes Terrae 〉Kaire Nõmm

ESSAY

Facing Away from the Sea 〉Indrek Allmann

ESSAY

The Baltic Sea Commons. Closer to the environment through (landscape) architecture 〉Katariina Mustasaar

RESEARCH

Baltic Vernacular. Experiments in research, teaching and practice 〉Susanne Brorson

REVISIT

Muhu Hut 〉Mihkel Tüür

IN PRACTICE

Ateljé Ö 〉Joel Winsnes, Mats Wahlström Walter

PROJECT

Kärdla School. Hiiumaa, EST. Arhitekt Must 〉Kadri Klementi

ESSAY

On Being an Island… 〉Johan Tali

Islands

Islands have always inspired mystical tales—in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the wildness of Prospero’s island, which he controls only by the means of his sorcery, is juxtaposed with faraway civilisation; on his way to Finland, Kalevide makes an island stopover, which culminates in him falling in love with the enchantingly singing Island Maiden; there are some who believe a free-trade zone on (artificial) islands between Finland and Estonia could bring unlimited wealth, and there is one man’s dream of a casino island right next to Tallinn that has intrigued, horrified and amused Estonians for a whole decade. Architect Johan Tali finds that a curled-up coastline gives conceptual space a clear boundary. As such, it attracts both utopians and escapists (p. 104). Can we also talk about distinctive island architecture and island space?

The islands of our region are connected by the Baltic Sea, which has been a more potent force in bringing ideas and people together than the map-drawn, but otherwise incorporeal state borders have been in separating them. Architect Katariina Mustasaar writes about the common space of the Baltic Sea, and the potential of seascapes in strengthening the connection between people and the broader environment (p. 44). One type of building that stands on the boundary between land and sea is the harbour. For maritime communities, small harbours play an important role in tourism infrastructure, but also in promoting local fishing. With good solutions, harbours can support the development of seafaring, bring communities together and improve environmental awareness. Architect Indrek Allmann discusses how harbours, which had been considered mainly from the technical engineering perspective in Estonia, have moved into architects’ orbit of interest (p.30). On the other hand, architect Susanne Brorson from the island of Rügen focuses on studying vernacular building in the Baltic Sea area, and making use of her findings in contemporary architecture (p.58). 15 years ago, architect Mihkel Tüür likewise adopted the practicality of vernacular architecture in building his house on the island of Muhu. This resulted in a novel structural solution, and an organic space that has remained unique in contemporary Estonian architecture (p.72).

The population of Hiiumaa is growing almost imperceptibly for now, but what about the longer term—will global climate change and population growth lead to a large-scale relocation of people to the island where the climate is softening? In the distant future, this will be inevitable, as it is acknowledged in the emerging general plan of Hiiumaa, which is discussed by municipal architect Kaire Nõmm (p. 20). How to manage such growth? And how to avoid peripheralisation in the nearer future? Or, as historian and ethnologist Helgi Põllo puts it: ‘What to ask from an island, who to protect there and from whom?’ (p. 6).

Laura Linsi, peatoimetaja